Drawn by a light in the sky, we continue

to follow the road south. Dusk beckons, and with it, again will

come the devils that have tormented us on our journey. We hurry

on as the sun sinks behind the woods of the New Forest, exploding the

autumn sky into a vivid paintbox of gilt. Towering high above the

trees and silhouetted against the embers of fading sunset, Judge

Peterson’s slender gothic needle at Sway points ominously to the

heavens of advancing night. Demonic yellow eyes start to glow in

the darkest patches of old dead stumps, as we run down the jetty at

Lymington to jump at the last second, onto the departing ferry.

The tolling of a church bell drifts across the water as land looms from

the mist, while our cloaked pilot in the prow raises an arm, and points

a bony finger—our destination, The Island of Vectis!

Pick up any motor cycle encyclopaedia you like, and strangely,

hardly anyone seems even to acknowledge the existence of this maker or

its machine! The Scamp was the rather unlikely product of ship’s

mast manufacturers A N Clark (Engineers) Ltd from the even

more unlikely location of Binstead, on the Isle of Wight! It’s

quite baffling how a maritime company decides to get involved in moped

manufacture, but the Scamp project was started in 1967 as a departure

from the usual yachting business. With no previous experience in

the field, that really is some wild diversification! Still, all

credit to Clark; they bravely committed themselves with an imaginative

and unique motor of their own design and manufacture, mounted in an

adaptation of the CWS ‘Commuter’ bicycle.

Glass’s Index lists:

‘Scamp’ 49.9cc

(2-stroke) 38mm bore × 44mm stroke, introduced March 1968 from engine

no. E10001, frame no. U10327. Scamp moped

introduced. Single speed, auto. clutch, rigid frame, brakes

front 3½" hub, rear calliper type, tyres 12"×2", ½ gal. tank, direct

lighting.

There is absolutely no ‘stock’ reference material available for the

Scamp, the only source on this machine coming from original literature,

club archives and records of enthusiasts’ contacts with the

manufacturer, so we really have to make the most from this information,

and study of surviving examples.

Our test feature machine today is engine number E11850, frame number

V12063, still in original condition and finished in red with gold

pinstripe. This bike is the highest frame serial so far recorded

by the register, and by contrast, also for the photoshoot, the second

blue bike displays engine no. 11955X, and the lowest recorded

frame serial: V10316.

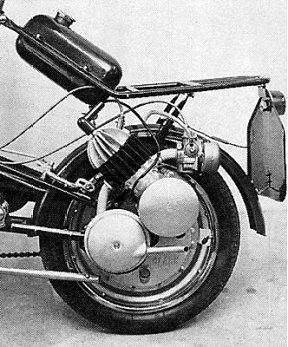

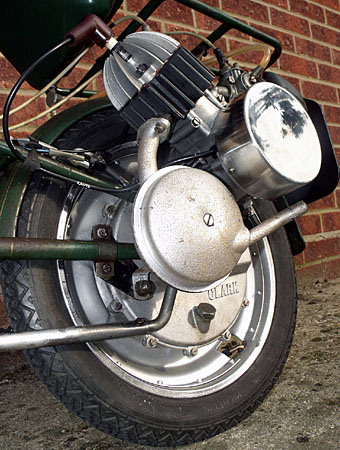

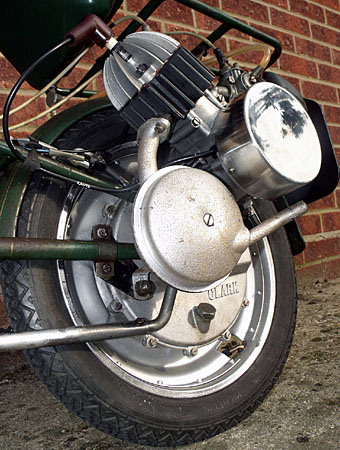

Mounted on the left-hand side of the rear wheel, the conventional

piston-ported engine features radial finning on its alloy head and cast

iron cylinder. The crankshaft is most unusually constructed in

that the flywheels bolt together by socket cap screws, through the

big-end bearing core, with the con-rod seeming to run on uncaged roller

bearings, so the whole assembly would appear home serviceable with no

more than a simple Allen key! A Dansi flywheel magneto hangs off

the nearside journal, while the drive outputs to a simple single-stage

centrifugal clutch.

The rear ‘disc’ wheel is a primitive assembly comprising of a Dunlop

12"×2" rim crudely

bolted and riveted through the spoke holes to a pressed steel disc form

fixed to a driving flange. It may be little surprise to find such

wheels often display some buckle effects. The flange rotates on

bearings around the rear axle, driven on a shaft from a large reduction

gear running in an oil-bath alloy case, and powered by a pinion shaft

from the clutch drum. Turning a ‘power key’ located in the clutch

housing enables the drive to turn the motor by a counterbalanced nylon

pawl engaged through a slot in the clutch drum. Once the motor is

started, centrifugal force overcomes a spring to disengage the

pawl. The automatic clutch operates as motor revs are further

increased. Switching back the ‘power key’ disables the pawl as

the clutch rotates into contact, returning to bicycle function.

The feature bike’s motor is fed from an original fitment

12mm Amal 369/162 carburettor, though

the rider’s manual clearly illustrates a Dell’orto, so probably both

types could be fitted. The exhaust comprises two steel bowls

bolted together to form a chamber, and is easily stripped for

de-carbonising.

With its 12" wheels and 16"×2" tyres, the CWS ‘Commuter’ cycle borrows

much of its general impression from the RSW16 bicycle and Raleigh Wisp,

which pre-date the Clark by a couple of years. Adaptations to the

bicycle feature a hub front brake (though a calliper set is retained

for the rear), Radaelli saddle, specially wide rear rack mounting the

triangular petrol tank in its crook, fitment of a basic lighting set,

and suitable control equipment. The cycle propstand is woefully

inadequate for the bike as a moped, and any attempt to precariously

balance the machine on this flimsy leg is merely inviting the

inevitable. You might as well save time & trouble, and simply

throw the bike down on its engine side every time you park!

Leaning against walls or even backing the pedal against a kerbstone is

far less hazardous.

The lattice cycle chassis looks pretty impressive in its design and

structural construction, being the nearest interpretation imaginable of

a small-wheel version ‘Mixte’ frame, but anyone who’s ever ridden the

notoriously twitchy Raleigh Wisp is going to approach a Scamp with some

trepidation. It has much the same geometry as the Wisp, but with

the engine mounted at the rear wheel, the centre of gravity is going to

be further back—oh dear! Still, one has to remain optimistic!

Engage drive mode by pulling down the ‘power key’ and latch into

position by rotating it 90°. In drive mode, the Scamp can be

reversed easily on the freewheel, but moving forward will now turn the

engine, so needs the decompressor engaged to enable navigation.

Pull on the petrol tap at the fuel tank, and the choke is—a strangler

on the back of the carb down by the rear wheel! No linkage

control, no throttle latch; you can just bet this going to be

awkward! We pedal up the road on the decompressor, drop the

lever, and the drive disengages so we coast to stop with the drive pawl

clicking. The pawl doesn’t latch again until the bike stops

moving, to allow another starting attempt—with the same result.

During starting, it seems the pawl instantly disengages whenever the

engine stutters, and the trick is getting it to catch and run as soon

as the motor fires. This could take some time!

There is a primitive sort of tickle device on the carb, which

comprises the top of the float needle sticking through a hole in the

float chamber top. You can press this to flood the chamber,

though it doesn’t seem to offer any discernible advantage in the

starting procedure, and a veritable disadvantage would appear to be as

a direct access point to allow rainwater into the float chamber!

It takes several attempts before the engine does continue running,

but then you’ve got to stop and dismount to open the choke

shutter! To stop it stalling (since we don’t want to go through

the starting palaver again), the tendency is to keep it on the

throttle, but the automatic clutch drags and the bike tries to make off

down the road—so you have to hold on the front brake now, while you try

and open the strangler with your left hand down by the rear axle!

This proves hopeless if you’ve made the mistake of dismounting to the

left side, possible but awkward if you dismount to the right.

Once the choke shutter is actually open, it’s just as well to lift by

the rack to get the back wheel off the ground and rev it a bit on the

throttle to clear its throat. Now the engine starts to run slower

without dying out, we can remount and get underway.

A lot of these starting difficulties would certainly have frustrated

most customers, and it’s baffling as to why they ever sold machines

fitted with the Amal carb? The Dell’orto with its latch choke

mechanism would have been so much more suitable.

Anyway, back on the bike and off we go, open the throttle, and the

single-stage automatic clutch locks on in one bite at quite low revs,

so the Scamp really just chugs off the line. If you want

acceleration, then it’s going to have to come from your own leg

power! As we start to build towards cruising speed, one also

starts to become aware of the handling characteristics. Take a

hand off the bars to signal, and the Scamp feels as if it’s poised for

any opportunity to go chasing rabbits in the bushes! Just a

little more edgy than a Wisp, but the Ariel 3 is still number one

on the top 20 chart of ‘Bikes that are trying to kill you!’

Once the motor gets warmed up, Scamp cruises happily up to

25mph, above which vibrations start

coming in through the Radaelli seat and the ride becomes

uncomfortable. Hot engine, on the flat, with light tail wind, our

pace bike briefly glimpsed a very best of 30mph. Downhill, 34mph maximum—and that really wasn’t going to go

any faster! Speed falls away readily as the bike encounters any

incline, but it still manages to labour slowly up moderate hills at low

revs without the need to pedal, as the motor digs-in once it falls

below 20mph.

Both brakes prove suitably retarding when required, with even the

rear calliper function proving surprisingly effective, though small

wheel machines would typically be expected to deliver better hub

braking performance anyway, advantaged by the basic law of physics.

The flywheel magneto is a Dansi set, and the Clark rider’s manual

specifies lights of 15W front &

3W rear, but put in these wattage bulbs and

the dimness is unimaginable. More practical illumination is found

by reducing the ratings down to only 3W for

both front and rear, so perhaps the generator coil might be somewhat

down on output?

Scamp’s motor ran smoothly and evenly throughout the trial with

never any hint of four-stroking, a confidence inspiring little engine

that, once you’ve got it going, feels as if it’ll run as long and far

as you like. Getting started however is a most deterring

operation, and would obviously have proved unsuitable to many customers

for practical everyday transport. To make this situation even

worse, the plastic drive pawl developed a further reputation for rapid

failure! Clutch function also appears to engage prematurely and

makes slow running and acceleration operations un-conducive, while in

the longer term, all the working components of the clutch are cast from

zinc and very prone to complete disintegration. The rigid frame

and forks, in combination with the small wheels and vibration effects,

quickly prove fatiguing; then add these factors to the sedate

performance and spooky handling, and you’ve got a machine that the

rider probably isn’t going to enjoy for long.

Tragically, the Scamp never found time to evolve, since it came and

went in the same year! Glass’s Index lists the bike as

discontinued in November 1968. It was reported from Clark’s that

they ‘…could not compete with the Japanese and Continental companies

already established in the market. Due to continuing financial

difficulties a Receiver/Manager was appointed by Lloyds Bank resulting

in a 50% staff reduction at Binstead and a complete disposal of almost

all finished machines and components…’

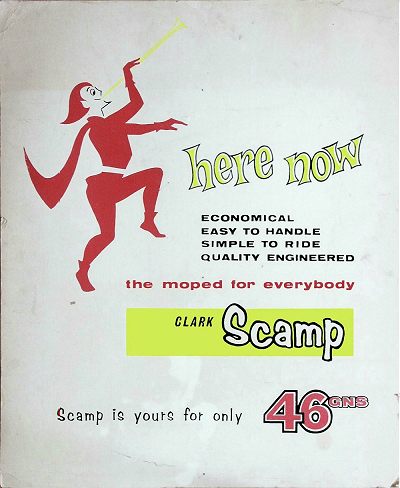

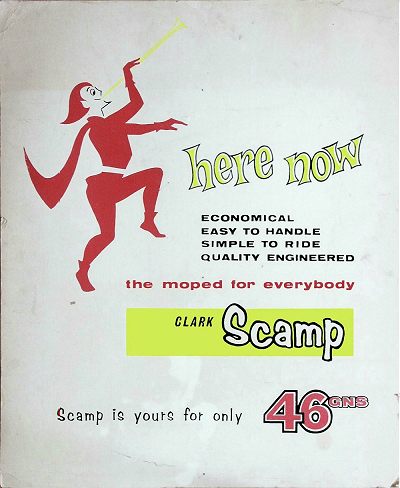

Clearly a catastrophic conclusion, but why the situation occurred

isn’t really explained. With a selling price pitched at

46gns, the Scamp was appreciably cheaper

than its most obvious market competitor, the Raleigh Wisp at

57gnss, which was selling very well.

On the face of it, prospects for the Scamp might have looked pretty

good, but the ‘continuing financial difficulties’ element could suggest

that the company trading position might have been struggling for some

while. Reading between the lines that yachting work was failing

to support the company around this time, the Scamp project was embarked

upon as an alternative business generator. Though March might

have looked an ideal time to launch the bike to catch the start of the

sales season, Clarks seemed unaware of motor cycle marketing practice

of showing machines the previous November at Earls Court to ‘prime the

trade’ and initiate the advertising for advance orders. Trying to

find period magazine road tests or articles on the Scamp is practically

impossible, and Clark’s very own poster even fails to show a picture of

the bike!

What seems to have happened was that Clark found themselves still

sitting on a whole load of complete machines, cycles, engines and parts

at the end of the summer as a lack of advertising had failed to

generate sales. The season had passed, and a struggling company

was stuck with all the stock value—a classic formula for cash-flow

foreclosure. Big banks don’t tend to have much patience with

small companies trading in the red. Everything was flogged off

any way it could go, even chassis without engines were fitted with

standard cycle wheels at the back and simply cleared as bicycles.

Out on the streets, these could be readily spotted from the standard

CWS Commuter, by the dedicated Clark rear carrier with its big hole

where the petrol tank was intended to fit.

With a variation of the name, a new business rose from the ashes and

still trades today in Binstead on the Isle of Wight as Clark Masts

Teksam Ltd, and Clark Masts (Technical Services) Ltd. spare parts

company—but don’t expect them to supply any parts for your moped,

that’s all long gone.

No official figures are known of how many Scamps were actually made,

but the company suggested 3,000–4,000. With the frame series

seemingly starting from 10000, and considering our test machine is the

highest frame serial so far recorded by the club, a statistical

projection suggests the total is more likely to be within 2,500.

How many survive today? Who knows? However, it’s certainly

a lot more than some of the ridiculously low numbers being claimed in

most of the adverts by people trying to sell them!

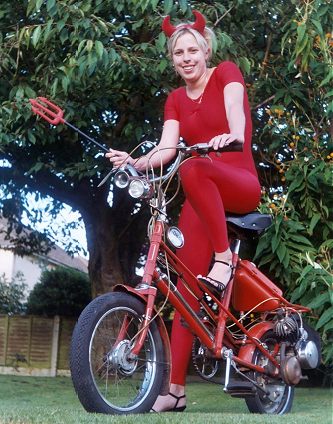

Some say that God rides a Harley, well that may be a little

controversial—but if ‘Old Nick’ were to claim his own machine, who

knows? It might just be the Clark Scamp…

Next—The brief window of opportunity opens, to test another rare

autocycle as it passes between private collections. Such fleeting

chances come Out of the Blue, and there’s no

time to think—just grab the camera, notebook & pen, and go! The

dials of our time machine spin backward again, to another

adventure. A shattered Europe stumbles back to its feet, and it

is the old machines that will have to rebuild the new world. The

most economic motorised transport is particularly in demand, and sharp

commercial eyes spy an opportunity as Autocycles are emerging for their

second generation.

This article was produced with the

assistance of

Clark Masts Teksam

Ltd

This article appeared in the July 2007 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2007 M Daniels. Montage ©

2007 A Pattle]

This will probably remain the most definitive reference article on the

Clark Scamp—so in making this little piece of history, we believe in

doing the best we can with the resources we have on the day, since it’s

pretty unlikely we’ll get the opportunity to visit it again—or so we

thought. However, one of the benefits of publishing on the Web is

the feedback we get and, in the case of The

Devil, one such e-mail has shed new light on the demise of the

Clark Scamp. So this is not the end of the story, the Devil will be riding out again later.

Speak of the Devil…

Dear Mark,

I was the first owner of Clark Scamp KJE 90G, which I bought

for £35 in 1968 from Allin’s cycle & autocycle dealer on Bridge Street

in Cambridge. I drove it home only to find that the front number

plate readd KJE 90G, so back to the shop for new transfers.

In those days you needed L-plates, but no crash helmet. Insurance

was 30 shillings per year (yes £1.50).

What a vile little machine! The cylinder head wobbled around,

making a lot of vibration. The engine connected to the bike frame

with a flat plate link. This fractured due to the vibration. The

rear light kept blowing due to vibration, so I hung the rear number

plate on leather straps. The centrifugal clutch wore out so I

riveted on leather ‘clutch plates’ instead. The advertised

200mpg was more like

20mpg when you opened the

throttle. I used to go to Marshall’s Garage on Jesus Lane for

petrol and a shot of Redex. Sediment always collected in the

neoprene fuel line.

I went back to Allin’s for a chat and they told me to chuck the

Scamp into the river. So much for after-sales service.

Wonder how many more Scamps are at the bottom of the Cam?

I never used the Power Key. It was only used if you wanted to

push the bike any distance by hand.

Method of starting the engine:

Tickle the Amal carburettor

Shut the carburettor intake disk

Open the decompresser using the handlebar lever

Stand to the left of the bike

Left hand on the throttle

Lift the rear wheel off the ground using the rear

carrier

Press down on the bike pedal to turn the engine

over

When the engine fired close the decompresser

Open the carb air intake disk

In 1969 I rode the Scamp from Cambridge to Peterborough, to catch a

train up North. The spark plug fouled up on the way to

Peterborough, so plug spanner in operation. Up North I got a rear

tyre puncture. Not possible to remove rear wheel, so puncture

repaired with bike lying on its side.

I then passed my driving test in Cambridge in a Ford Anglia 105E, so

off came the Scamp L-plates. I last used the Scamp in the early

1970s then gave it away. Just out of curiosity I Googled Clark

Scamp and saw my old bike on your website.

All the best from

Peter Dockerty.

[The old log book for KJE 90G lists just Peter

Dockerty as the first owner and Anthony Silvey next. The change

of ownership was never stamped and the bike wasn’t taxed after August

1971, so it looks as if Mr Silvey never got it to work well enough

to use.—Andrew]

This letter appeared in the April 2012 Iceni CAM Magazine.

Making The Devil

So what was it like producing

The Devil Rides Out? Difficult all the

way is the best answer. Taking several years in research and

generation, source material was the biggest problem, since so little

was available, and it was very hard to turn up much more than scraps of

anything new, so it mainly came down to collation, careful analysis of

what there was, and statistical projection. Once we’d finally got

the bike to work, the road test went well, and the main text on this

one came together fairly quickly—but the original ‘maritime’ intro

never felt right and didn’t let the story flow from the previous

link. So in the end, it got ripped right out, binned, and

completely reworked. The ‘demon journey’ was the final result,

travelling south and crossing the Solent to the Isle of Wight.

Vectis was of course, the old Roman name for the island, and it all

started tumbling into place like some antique Hammer horror.

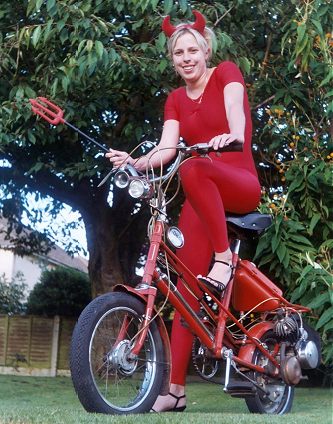

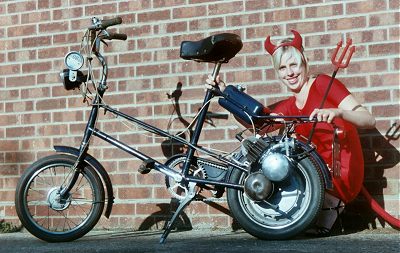

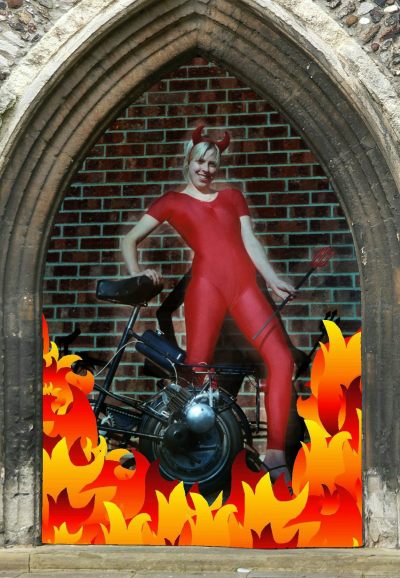

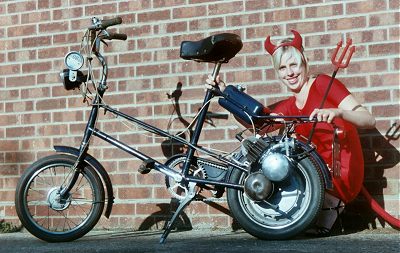

The ‘little devil’ photoshoot had long been planned to match with

this article, way back years ago, when the project to produce the

feature first started. I guess the idea was inspired by the

original advertising poster. Scamp’s tiny wheels and low engine,

coupled with falling sun angle of early evening, meant practically all

pics had to be taken at low angle to avoid shadows—but not until

Rachael got kitted up, and framed in the viewfinder for the first shot,

with the sunlight flashing off that red leotard; only then you know it

really is going to work! With the shadows lengthening, the shoot

had to go quickly, with fast changes of set and location to follow the

light. Two rolls of film clicked through in 45 minutes, away

in the post to the developers on Monday 18th June, and a fast closing

deadline for Iceni2 at the end of the week. The film and discs

came back on Saturday 23rd, then straight on to Andrew for digital

additions. With the gothic arch and flames dropped into the lead

picture, final lay-up of the magazine could progress, and then there’s

all the printing to do! The timing certainly ran a bit tight on

this one, and it sure was a scramble to get everything completed for

Peninsularis, but we made it—just!

The Devil Rides Out hit a final bill of

£92 to complete the article, (film/developing/CDs £29, costume and

props £30, fuel £33), so you can see exactly where the money goes, and

all donations go directly towards production.

Devil’s Epitaph

2008 sees 40 years since the introduction of the Clark Scamp, and

the anniversary of our presentation on the machine.

While our previous article ‘The Devil Rides Out’

covers the Scamp in feature, following its publication last year

further researches have turned up fresh material and revelations have

bubbled to the surface as a result of our readers’ responses.

It seems that Clark was adopting its own original methods to market

the Scamp, employing sales rep, R T Townson, to travel the

country, making personal calls on motor cycle dealers to establish

agencies and secure orders. At this time, in the mid to late

’60s, there was an on-going government-initiated programme to promote

British goods and manufacturing—anyone remember the ‘I’m backing

Britain’ campaign? There are references by Townson that Clark had

also been following this theme to promote the Scamp.

Glass’s Index listed the Clark Scamp from March 1968.

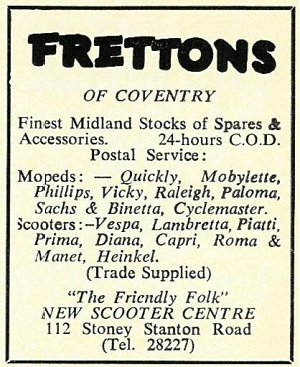

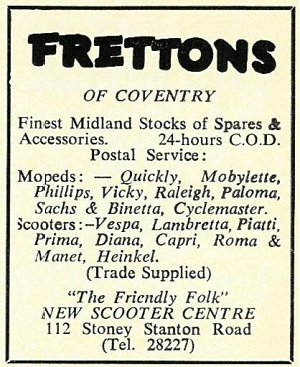

Managing Director of Fretton’s of Coventry, and Chairman of the

National Association of Cycle & Motor Traders Committee, Reginald Reed,

produced a moped sales presentation to the Blackpool Council meeting of

21st March 1968, and previewing the forthcoming motor show at Belle

Vue, Manchester on 3rd April. This report included an outline of

the introduction of the Clark Scamp moped produced by Alec Clark from

Binstead, Isle of Wight, as an entirely new machine to be listed for

£48–6s–0d (46 Guineas), and being price-pitched as ‘the cheapest

machine of the year’. He went on to somewhat generously describe

‘The performance is lively [we wouldn’t!], maintenance remarkably easy,

though the ride is rather noisy and a little rough—but remember the

price—and it should find a ready market’. Then closing with the

statement that, ‘It may not be on view at Manchester, however’.

We came upon some interesting factory publicity pictures, showing

two early Scamps, both with Isle of Wight KDL series registrations that

reasonably date them to late 1967. The people in the photo are,

most likely, members of Staff at Clark: we have identified the man as

David Bennett, Clark’s Sales Director. The picture was probably

taken quite close to the factory although the area is now covered with

houses. A close-up picture is further interesting in that it

shows the engine fitted with a large Dell’orto carb, certainly the only

one we have actually seen. Although a few production machines had

the Dell’orto carb, the majority appeared with the Amal 369/162.

IceniCAM reader Paul Sugden relates that

the Scamp moped was the subject of a ‘Breach of Confidence’ case raised

in 1968 by a Mr Coco against A N Clark Engineering, for

manufacturing the moped engine from his drawings.

In 1965 Mr Coco began market research into the possibility of

producing a new moped, and proceeded to design one. By March 1967

a batch of pistons had been made for him in Italy and sent to him in

England. In April 1967 there was the first contact between

Mr Coco and A N Clark about the proposed moped and the

company expressed interest in making it. In a letter dated

24 April 1967 the company asked Coco to bring the prototype that

he had built to the works of the company. Over the next three

months there were many discussions between the parties and Coco

supplied Clark with information and drawings towards the production of

what had come to be known as ‘the Coco moped’. Clark did work on

Mr Coco’s ideas and also put forward draft documents concerning

the financial arrangements between them, but these documents were never

signed and terms were never agreed.

On 20 July 1967, A N Clark told Mr Coco that the

transmission of the Coco moped was creating a serious problem of

excessive wear to the rear tyre and that the company had decided to

abandon it and make its own moped to a different design. The Coco

moped used a roller-drive to the rear wheel. When the Scamp

appeared on the market, although it used a completely different

transmission, the engine was substantially similar to Mr Coco’s

design.

Mr Coco sued for breach of confidence in disclosure of his

drawings.

There was a preliminary hearing where Mr Coco applied for an

injunction to stop production of the Scamp as ‘interlocutory

relief’. The injunction was refused. Clarks undertook to

pay a royalty of 5/- (25p) for every Scamp engine manufactured into a

special joint bank account on trusts. The full trial would then

decide how much, if any, of the accumulated money would be awarded to

Mr Coco.

However, the trial never took place, the Scamp was discontinued, and

Clark went into administration.

Glass’s Index entry confirms production of the Scamp as ceased in

November 1968.

Despite not going to trial, the Coco v A N Clark

case established quite a legal landmark, and is still widely quoted in

legal cases as a test case example for breach of confidence.

It would certainly be of interest to add a reference copy of the

original Coco drawings to IceniCAM Information Service files, if anyone

might be able to turn up a print?

This epitaph could finally lay Scamp’s listless soul to rest, yet

still may not be the last word on this haunting spirit. Even as

this passage is typed, an ongoing engineering project could mean that

the little devil may return to grace these pages again someday—in some

rather unexpected form!

Further information

Clark documents in the On-line

Library:

Coco v Clark CH full text

Coco v Clark CH short text

Scamp accessories leaflet

Scamp adverts Trader 1967-12

Scamp adverts Trader 1968

Scamp article Trader 1968-02-23

Scamp article Trader 1968

Scamp clutch service sheet

Scamp instructions

Scamp leaflet

Scamp news Trader 1967-10-27

Scamp news Trader 1967-11-24

Scamp news Trader 1968-01-05

Scamp news Trader 1968-02-02

Scamp news Trader 1968-02-16

Scamp news Trader 1968-03-01

Scamp news Trader 1968-03-15

Scamp news Trader 1968-04-12

Scamp news Trader 1968-06-07

Scamp news Trader 1968-06-31

Scamp parts list

Scamp parts list update

Scamp parts price list

Scamp poster

Scamp Trader supplement

This article first appeared in the July 2008 Iceni CAM Magazine and

was later updated with more information on the Coco moped.

[Text © 2008, 2011 M Daniels & A Pattle.

Gravestone picture © 2008 A Pattle. Period pictures from IceniCAM Information Service]

Who was Mr Coco?

Information about the Mr Coco who

suggested a moped design to Clark is not easy to find … who was

he?

On 25 November 1948, The Motor Cycle

reported the arrival in Britain of three Italians who had ridden all

the way on Mini-Motors which, in the picture below, look as if they’re

mounted on very un-Italian Hercules bicycles. Their arrival was

planned to co-incide with that year’s Earls Court Motor Cycle Show and

thus to pubicise the launch of the Mini-Motor in Britain.

The three riders were: Vincenti Piatti (designer of the Mini-Motor),

Mario Coco (described as a technical illustrator), and C

Garbardi-Brocchi (a journalist). Is this the same Mr Coco?

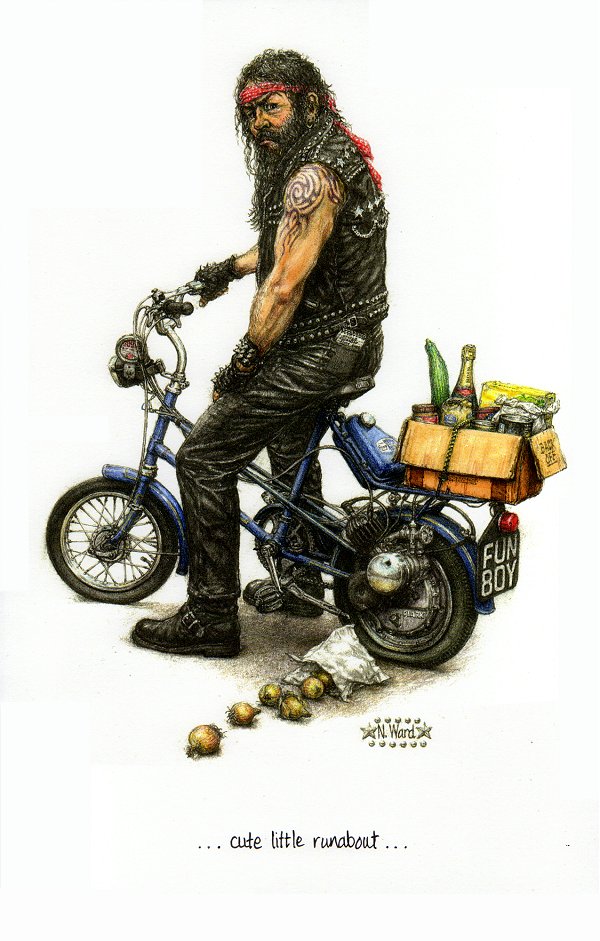

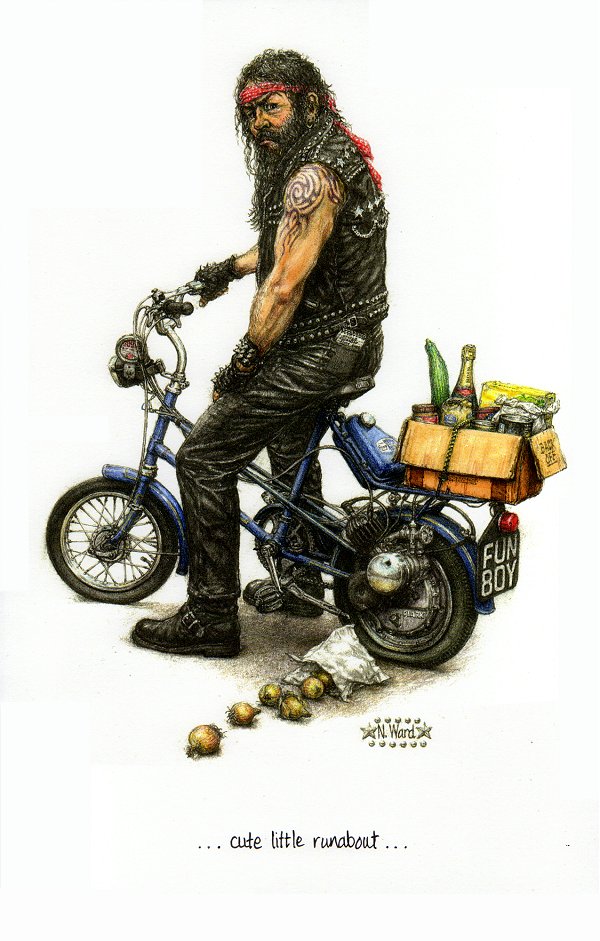

More Devilry

IceniCAM readers may be aware of the

motor cycle drawings by Nick Ward that

regularly feature in Classic Bike

Guide. Co-incidentally, Nick’s drawing in the June 2008

edition of CBG featured a Clark Scamp.

Not just any Clark Scamp either, the model for the drawing was the blue

Scamp that was featured in our The Devil Rides Out

article.

© 2008 N Ward, all rights reserved

We are grateful to Nick for supplying us with a copy of his original

drawing and for granting us permission to reproduce it on this

website.

The Devil’s Disciples

Some of the people involved with the Clark Scamp

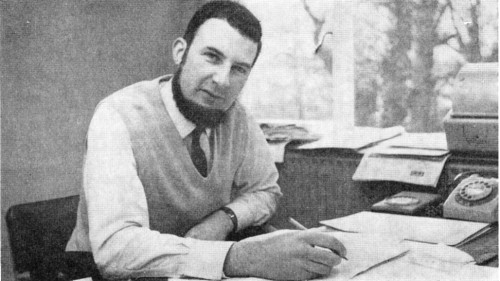

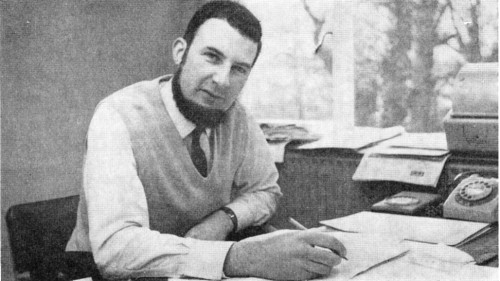

‘The Man Behind the Scamp’: founder of the company, Alec Clark.

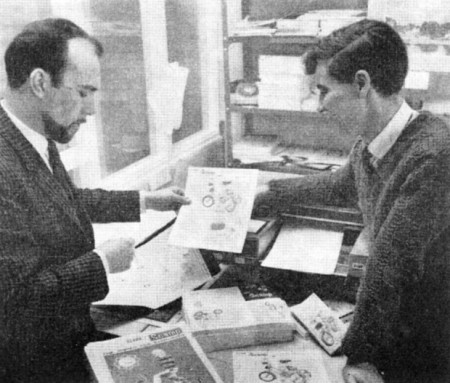

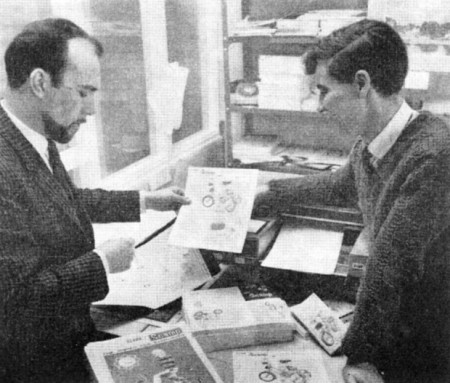

In the publicity Department: John Wright (left) and Vic Vine

(right).

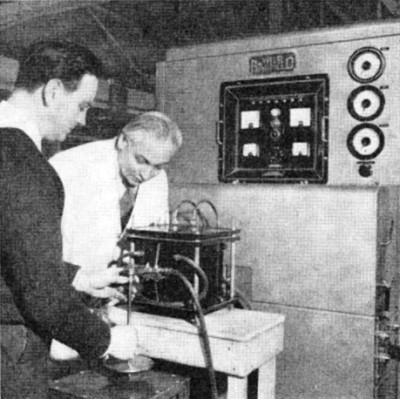

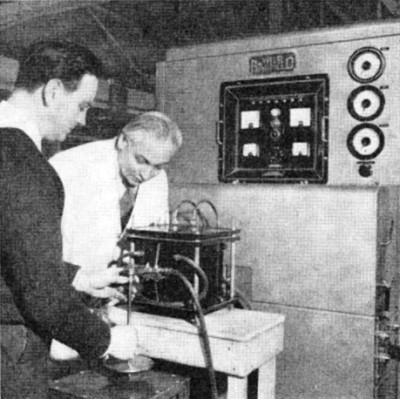

Production Director Ken Phipps (left) and Machine-Shop Foreman John

Saunders (right). The equipment they are working with is a Wild

Barfield HF induction heater that was used for hrdening components

such as the drive pinion and con-rod.

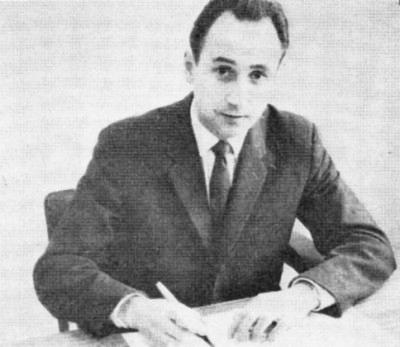

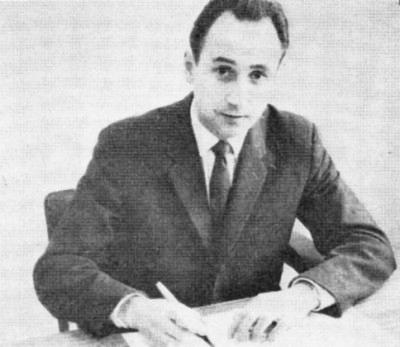

Sales Manager: David Bennett.

David Bennett & Ken Phipps outside the factory.

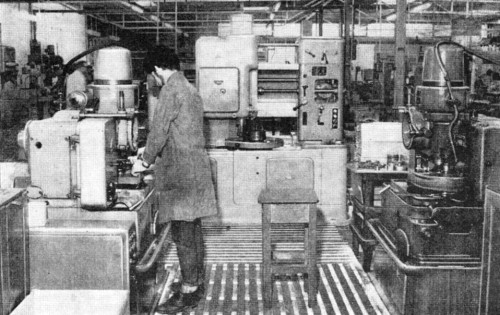

Making the Clark Scamp

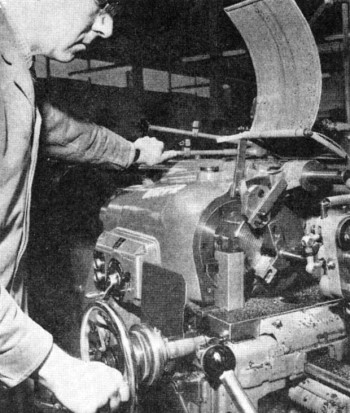

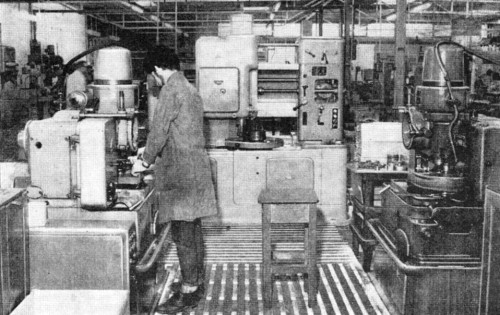

These three gear shaping machines were used to cut the teeth on the

drive pinion and the main gear.

An Avery metal hardness tester being used in the Quality Control

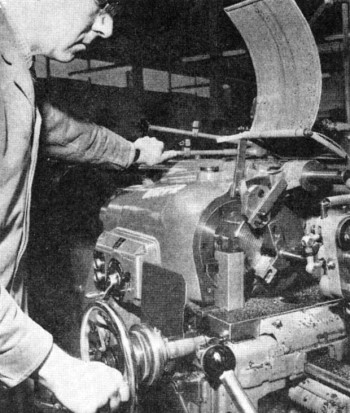

department to check the hardening of a rear wheel axle.

A crankshaft being machined on a Ward 3CA capstan lathe.

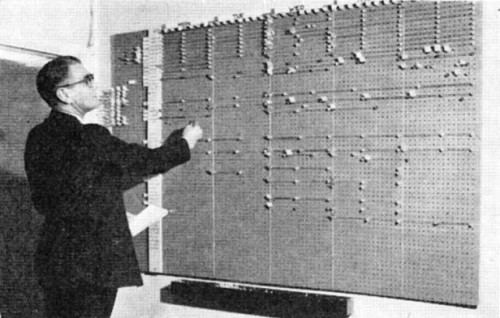

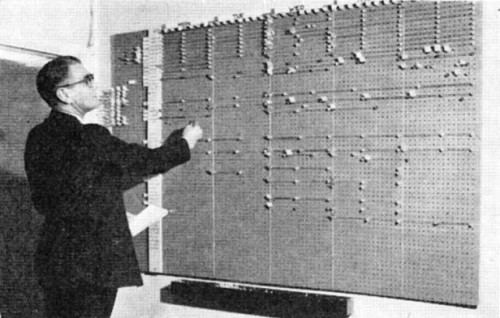

In pre-computer days, this peg-board was used in the Production

Control department to keep track of what was going on in the

factory.

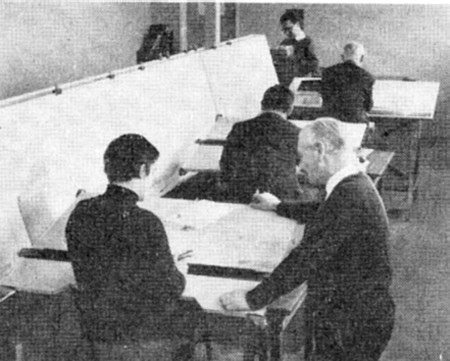

The Drawing Office.

The first production batch of Scamps waiting to have their engines

fitted.

Road to Hell

The Coprolite Run in 2011 was witness

to an unprecedented Clark Scamp

flash mob! Among this demonic turnout were two Scamp motor

wheels on display in the hall and eight bikes, of which four were

green, three red, and one blue. Half the Scamps remained on

display, while two green, one red, and one blue were ridden at the

event. Our tale starts by following the exploits of these two

little green devils along the Coprolite course…

The four Scamp riders at the 2011 Coprolite Run. [Photo: Kell McLean]

It was an extraordinary moment to have four Scamps leading out the

run from the car park, then out along the route, though by the time

we were approaching the two-mile marker into Kirton, other bikes were

already starting to nudge ahead—Scamps it seems, may not be to

everyone’s taste … just because they’re slow?

By the time we were heading around Gulpher Road there seemed to be

more bikes pushing ahead and disappearing into the distance than

there were left behind—err, where is everybody?

Approaching the end of Gulpher Road, my ‘Green-1’ was seemingly

developing a bit of a rattling noise from the engine department, and

stopping for a check-up before the Golf Course revealed one of the

top-end studs had vibrated out of the crankcase, so continuing gently

for the last mile, I cruised in to the Ferry Boat Inn car park at

Felixstowe Ferry among the later arrivals. A quick spanner

check at this halfway stop re-tightened the stud ready for the return

leg, so Chris Day on ‘Green-2’, and Dave Watson on ‘Blue’ had arrived

before me, while Andrew Pattle on ‘Red’ became disabled with a rear

wheel puncture, which is a major fix on a Scamp, so ‘Red’ was down

and out.

The homeward trip on ‘Green-1’, V 10721 was more prudently

navigated along the direct route at low speed to minimise the effects

of further vibration-related issues, while Chris on ‘Green-2’ opted

for the full course at full speed.

Joining up again with the other two Scamps on the road back

towards Bucklesham, ‘Green-2’ U 11024 now had its front mudguard

strapped to the rear carrier, apparently having vibrated out all its

mounting bolts, until it fell down onto the wheel, and Chris had

subsequently ridden over it!

‘Blue’, ‘Green-1’, and ‘Green-2’ completed the course, but

vibration was certainly an issue.

The only way to reduce the vibrations was to ride slower…

Following the Coprolite Run, we performed further road tests and

photo-shoots on both green Scamps.

Road test ‘Green-1’, VBJ 116F, Frame number V 10721

(frame numbers started from 10000)

This bike is fitted with a Dell’orto SHA 14/12 carburettor,

whereas when we tested ‘Blue’ and ‘Red’ in the original Devil Rides

Out article back in July 2007, both those machines were fitted with

Amal 369/162 carburettors.

Starting is much easier with the Dell’orto carb, compared to the

Amal as fitted to other Scamp models. Click down the choke

lever at the carb, just in front of the air filter. Turn on

fuel under the right side of the tank.

Switch the ‘power key’ (underneath the crankcase) into drive

position to engage the starting pawl. Hold in the decom-pressor

lever under the left handlebar cluster, then pedal off. This

requires a certain amount of physical effort to maintain, since the

decompressor venting doesn’t appear totally effective, but the engine

readily fires with a light tweak on the throttle and is soon coughing

against the choke, so open the throttle wide to automatically release

the strangler latch, and Scamp gasps in a few good cylinders-full of

air to clear its little lung.

Running quickly settles down to a crisp and mellow popping, with

little tweaks on the throttle being responded to with eager little

snatches on the automatic clutch. Scamp seems keen to go, so we

take off from the kerb. The automatic clutch bites fairly

readily, at which the high load and low revs situation makes Scamp’s

motor suddenly appreciate that pulling off is going to represent more

than it can manage without some assistance, so we help with a little

boost on the pedals to get through the initial movement phase.

Once away, the exhaust tone clears to a flat drone, with a hopeful

urge as Scamp gets stuck in to acquiring some pace. Describing

this as acceleration would probably be an optimistic term, as waves

of vibration flood in through the pedals from 10mph, increasing in frequency as the revs

creep up. It soon feels very much like you’re receiving an

electric shock through your feet!

The bike seems to get through the worst of these vibrations by the

time its crawled a little past 20mph, so it proves better to settle for

general cruising between 22–23mph

(on pace bike tracking). Though this seems fairly close to

Scamp’s maximum on flat of 25mph,

it’s not actually thrashing the bike to death since the revs are

still relatively low, it’s just that the engine seems unable to pull

much more against its final drive ratio.

With no speedometer fitted, the pace bike tracked our downhill run

best at 34mph, but this

accumulated speed readily dropped away against the following uphill

gradient, right down to just 12mph, but ‘Green-1’ still doggedly crested the

rise without resorting to pedal assistance.

It has to be said that the vibration (probably due to poor crank

balance) was very tiring during our runs on this particular

Scamp. The only way to physically cope with our first couple of

‘impression’ runs of around 12 miles, was by riding the bike

slower. On the main test run after ‘holding off’ to warm the

engine for the first couple of miles, the remaining three to four

miles were ridden pretty much at full throttle. The vibration

on this main test run was particularly fatiguing, and made to seem

all the worse during the trial by constant cyclic drumming from the

reduction gear. These effects also take their toll on the cycle

parts as much as the rider. Vibration on the first ‘impression’

run managed to completely lose one crankcase screw and loosen a

second. Completing the main test run found the foot of our

side-stand had fallen out somewhere along the course! Readers

might be happy to know the pace bike retraced our tracks and found

the missing part in the road about a mile from base.

Though the rear calliper brake slowed down the bike adequately,

there was a number of complaining groans registered from the

straining brake blocks. The front drum brake proved more

effective and less stressed in operation, but you generally wouldn’t

want to rely on that alone. A considered balance of the two

brakes was certainly the best formula.

The original fitment Radaelli sprung mattress saddle is never

going to be any contender in the sumptuous comfort competition,

though it proved generally adequate for the more commonly short

distances at the typical low speeds that the average Scamp rider

might care to normally suffer the bike for. When running at

higher speeds, the vibration and constant road battering from the

suspension-less frame will come right through and scramble the

rider.

It appears that not all Scamps were born equal. The variable

quality of Clark’s machining and pot-luck crank balance could

seemingly result in a number of shades of grey!

The lighting arrangement on this bike was converted to 15/15W

beam/dip equipment with 3W tail, and the Dansi generator produced

good light from both lamps, perfectly adequate for the bike at night

considering the limited performance of the machine. The Miller

horn also produced an effective and easily audible tone.

It’s not very often we get to compliment effective electrics on

old bikes we try—shame about the rest of the Scamp...

Road test ‘Green-2’, XDY 855H, Frame number U 11024

with Amal 369/162 carburettor.

The remarkable thing about this machine is it’s the only example

we’ve seen fitted with a Huret speedometer set and marked as a 16×1.2

ratio Huret drive. This was apparently listed as a genuine

Clark accessory kit, and we’ve never seen a Huret drive like this

ever before. There’s obviously no question that this special

Huret kit existed to specifically suit the 12/16” wheel size, but we

can only wonder why Raleigh never offered the set for the Wisp?

As a reminder how much ‘fun’ it is starting a Scamp with the Amal

carburettor…

Pull on the petrol tap at the fuel tank, and the choke is … a

strangler on the back of the carb down by the rear wheel! No

linkage control, and no throttle latch to release it; you can just

bet this going to be awkward! There is a primitive sort of

tickle device on the carb, which comprises the top of the float

needle sticking through a hole in the float chamber top. You

can press this to flood the chamber, though it doesn’t seem to offer

any discernible advantage in the starting procedure, and a veritable

disadvantage would appear to be as a direct access point to allow

rainwater into the float chamber!

It takes several attempts before the engine does continue running,

but then you’ve got to stop and dismount to open the choke

shutter! To stop it stalling (since we don’t want to go through

the starting palaver again), the tendency is to keep it on the

throttle, but the automatic clutch drags and the bike tries to make

off down the road, so you have to hold on the front brake now, while

you try and open the strangler with your left hand down by the rear

axle! This proves hopeless if you’ve made the mistake of

dismounting to the left side, possible but awkward if you dismount to

the right. Once the choke shutter is actually open, it’s just

as well to lift by the rack to get the back wheel off the ground and

rev it a bit on the throttle to clear its throat. Now the

engine starts to run slower without dying out, so you can remount and

finally get underway.

A lot of these starting difficulties would certainly have

frustrated most customers, and it’s baffling as to why they ever sold

machines fitted with the Amal carb?

Since Huret speedometers can never be trusted to deliver accurate

readings, the road test on ‘Green-2’ was accompanied by our pace

bike. Best on flat with tailwind paced 29mph (speedo bouncing between 32–35), downhill

paced 35mph (speedo very

ambitiously pinned around 40mph

on the end stop), and the following uphill climb slowed to

14mph before cresting the rise on

engine power alone (without any pedal assistance).

The Huret speedo presented fairly accurate indications up to 25 on

the clock, above which the needle began to swing increasingly wildly,

and became more optimistic in its indications, which were generally

taken as an average on the swingometer. There seemed fewer

vibration issues with ‘Green-2’, and less rider impression of cyclic

drumming than ‘Green-1’. There was also noticeably less transmission

noise commented on by our pace rider, who was mostly following on the

offside rear quarter.

Since our original Scamp articles: Devil Rides Out in July 2007,

and its follow up Devil’s Epitaph in July 2008, we’ve added a number

more items to the IceniCAM information service, including the full

Coco v A.N.Clark Chancery Division 13-page legal account details (or

five-page summary if you want the short version). It’s

certainly an interesting read, whether you agree with the final

outcome or not. From a technical point of view, Clark’s point

regarding the wear rate of CoCo’s roller drive to the small 16-inch

tyre was certainly very justified—drive roller induced wear would

have been diabolical on a 16-inch tyre diameter. Also much

focus of the outcome of the case was based on specific aspects of the

engine design, which (from an engineering point of view) seemed to

have (questionably) played against Clark, since just about every

variation the basic piston-ported two-stroke engine design had

already been made by just about everybody, and there was nothing

special about a bought-in proprietary two-stroke piston.

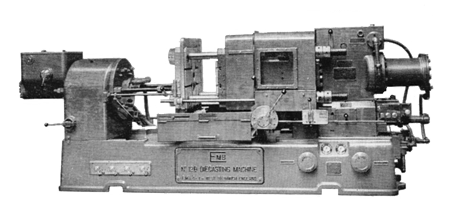

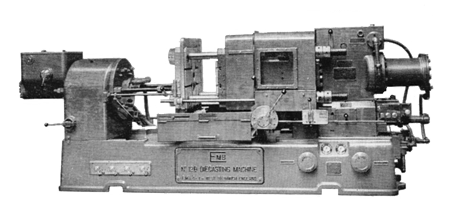

An EMB 12B Cold Chamber Diecaster—

as used for casting Scamp crankcases.

The legal action didn’t change the reality that the engine was

pretty dreadful. From an engineering aspect, the pinion design

to the ring gear required a difficult standard of machining precision

(that ANC obviously couldn’t achieve), to prevent the cyclic drumming

and vibration issues. Quality issues with crankcases full of

voids, suggesting the die-cast machines were not gas-boosted for the

initial charge phase, and just relying on a slower hydraulic

delivery. Further, the tooling was possibly not equipped with

suitable overflows to effectively vent the die, resulting in porous

castings, which allowed the crankcase studs to pull out since they

had insufficient material to anchor the threads. The zinc cast

clutch components, and starter pawl were all too frail and

consistently failed, and we could go on, but you get the drift, so

what’s the point?

Another interesting info file is the Scamp Accessories Leaflet,

which lists and illustrates the speedo kit, but instead of the

French-made Huret set, it shows a Dutch-made Lucia set!

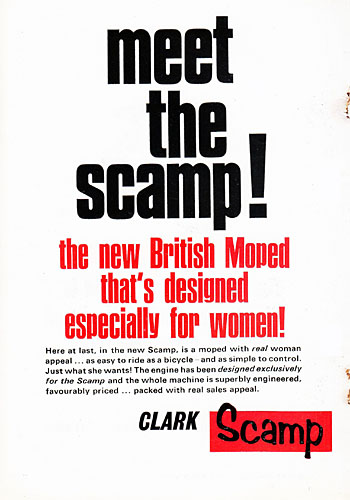

The period advertising files are hysterical, ‘designed for women’

… ‘err, might that maybe put men off from buying it?’ …. OK, we’ll do

a different ‘man’s’ advert too! Period marketing, no idea…

There are now 25 historical and fascinating Scamp related archive files in our IceniCAM Info

Service, all as free PDF downloads.

Next—If everything goes according to plan, then we might hopefully

be having a Derbi Day, but I

wouldn’t bet on it!

This article appeared in the April 2023 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2023 M Daniels.

Making Road to Hell

Since the famous Clark Scamp flash mob

was at the Coprolite Run in 2011, we could say this article has been

twelve years in the making—but you may ask why we didn’t produce it

sooner?

Following the Coprolite Run, some of the Scamps were displayed on

the EACC stand at Copdock Show in 2011, then Green-1 & Green-2 were

formally road tested and photo-shot in September and October 2011,

before both bikes were subsequently sold on. In the meantime a

further Scamp project was underway to adapt a Watsonian cycle sidecar

chassis to mount a Scamp motorwheel as a ‘pusher wheel’ that could be

attached to a bicycle.

Mopedland completed all the metalwork to adapt and fit the Scamp

rear wheel to the sidecar chassis, with an Atco lawnmower fuel supply

tank mounted above the wheel, and mudguard brackets. All the

technical mechanics were sorted, and returned to the customer for

finishing final assembly and fitting for operation. This Scamp

‘pusher wheel’ cycle was subsequently supposed to come back to us for a

feature and to complete the planned article, but the trail grew

cold. We presume the Scamp pusher wheel kit is still out there

somewhere, and may turn up again some day … but after 12 years we

finally gave up on the prospect of the intended article, and decided on

this rewrite to clear the decks.