This company holds one of the most unlikely records in the biking world, as the longest uninterrupted gap between selling motor cycles with its brand: 46 years!

Our tale starts way back in Victorian times, with the foundation of The East London Rubber Company by Alfred Kerry in 1877. The original premises were located in Lower East Smithfield, and followed the business of rubber merchants, branding its products with the ELRCo logo, and founding a path to success on the distribution of moulded solid rubber tyres to the builders of cycles, perambulators, and other carriage wheels. Since these rubber products involve a great requirement for imported raw materials, it’s probably unsurprising that Alfred Kerry’s name also appears in documentation of the East London Shipping and Dock Companies. By 1894, John Llewyllen Jones (Alfred’s son-in-law) was brought into partnership, and they progressively broadened the business into trading in bicycles, parts, and accessories. In 1898, ELRCo introduced its first retail catalogue, which was so well received by the trade that it became a regular annual feature of the company.

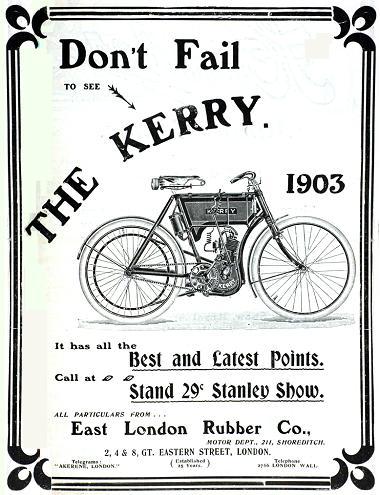

These connections naturally led on to the import of pioneering continental motor cycle engines by Kelecom and FN, associated cycle chassis components, and even the factoring of practically complete Belgian-made machines, which were badged and sold under the Kerry brand from 1902.

In 1903, the partnership was extended by the admission of another son-in-law of the founder, Herbert John Ball, who shared company control with John Llewyllen Jones for nearly 30 years following Alfred Kerry’s death in 1905. The advent of the motorcar presented further opportunities in this field, and Walter Hart joined the company in 1906 to take charge of the tyre department. The development of a chain driven motor cycle model in 1907 began an association that introduced the Kerry–Abingdon brand. Following two previous moves into bigger premises, in 1910 the company acquired a very large property at 29–33 Great Eastern Street, on the corner of Holywell Lane, going on to make this building’s façade famous to the trade through the firm’s catalogue, stationery and advertising, while during the same year, a second branch in Sheffield also moved to larger premises in Furnival Street.

Motor cycle listing ceased with the advent of the Great War in 1914, and from this time the catalogues concentrated on cycles, motor accessories, household, wireless and electrical goods. Leaving the army in 1920, Charles Kerry returned to work in his father’s former business, finally relinquishing the company’s last connection with the founding name when he sold out his interest during the recession as the business converted to a public company in 1934. This financed a programme of expansion, opening nine additional branches across the country over the following five years.

The Great Eastern Street premises and stocks were destroyed by enemy bombing in September 1940, leading to the acquisition of new headquarters at Stratford. As the Ministry of Supply’s requirements demanded their entry into machine tool manufacturing, it was decided by the directors that the name of East London Rubber Company was no longer relevant to the broader business, and in 1943 the title of Kerry’s (Great Britain) Ltd was adopted, and appeared on the cover of the annual trade catalogue from this time onward.

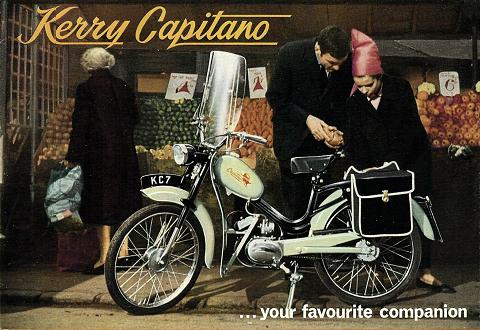

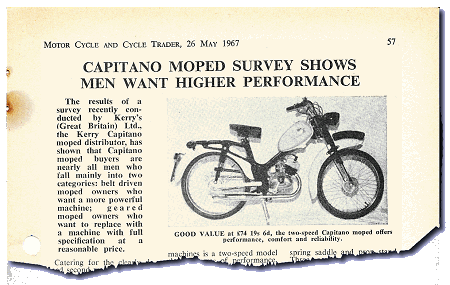

Having not sold a motor cycle under its brand for 46 years, Kerry re-entered the motorised market in July 1960 with a two-speed moped. Returning to established practice, the Capitano was a factored machine, built in Italy by Testi, and imported complete with a cast ‘Kerry’ badge plate on the clutch case of the Minarelli motor (which was a standard service feature of this engine supplier for factored customers), and Kerry decals simply applied to the petrol tank.

The Minarelli heart of Capitano tempted Kerry’s customers with a big edge over any other make; rated at 3.1bhp @ 5,000rpm it boasted the most powerful moped on the UK market! At this time, Phillips and Norman were fitting the 2bhp Villiers 3K motor, NSU’s Quicklys struggled back with only 1.4bhp for the two-speed and 1.7bhp for the three-speed, and Raleigh was about to ditch its Sturmey–Archer engine in favour of a new contract to use the 1.4bhp Motobécane! The competition was nowhere near and, overnight, Kerry returned as new King of the Mopeds!

Minarelli’s motor was robustly built, durable, and took everything the rider threw at it. Though only 7:1 compression ratio, the power came from big cylinder porting and an efficient T/412/S1 Dell’orto carburetter. Sparks came from a CEV flywheel magneto with a generator of 6-Volt, 18-Watt output; gear primary drive delivered to a tough multi-plate clutch; then on to the ratios, which smoothly and positively selected. The motor was a great little package … then look at the cycle specification: telescopic forks up front and swing-arm suspension at the rear, full width hub brakes, clean, simple and functional styling. Why would anyone want to buy anything else?

While the Capitano engine proved strong and reliable, the Italian standard of finish on the cycle parts at this time was justly earning itself a reputation for quality of a different kind! Given a couple of British winters, the un-primed paint would drop off the metalwork, chrome peeled like old Christmas glitter from all the plated items, assembly standards revealed themselves as inadequate as 13-gauge spokes fell loose and rims buckled, then the deterioration of under greased wheel bearings, and the Aprilia electrics failed, while mudguards and number plates also proved rather prone to vibration fracture. Unaffected by the disintegrating cycle parts around it, or the owner’s lack of remedial maintenance, the Minarelli motor kept relentlessly powering along—usually until the drive chain broke and smashed pieces out of the cases!

Over a period of time we’ve managed to ride our way through quite a selection of Kerry Capitano mopeds, so probably the best method is to work through them in chronological order. Frame serials are indicated by Glass’s as starting from 1001, and our first example is one of the very early dark/mid blue painted two-speed models, a little weathered by time, but nonetheless still totally standard and original. Wearing frame number 2478 and registered in 1960, we’ve been running this bike for the last 15 years as a workshop hack, and readers should be pleased to hear that it still serves in occasional use as a local commuter and rally vehicle. The forward frame on the right hand side carries a video camera when it’s being used for mobile filming at events.

Typically Italian, all the chrome plating has long dropped off, replaced by gunmetal metallic grey. The original blue finish has also largely gone, and been touched back by nearly matching brush paint. The headlamp shell features the optional extra of a 60mph silver faced Huret speedometer.

This initial two-speed model had a given weight of 100lb (7st 2lb or 45.5kg) so proves nice and light for easy handling.

Early Kerrys are much more comfortable to handle by their round tubular rear frame, while around 1964 the frame assembly changed to a pressed-steel fabrication with a metal edge that cuts into your hand when loading the bike onto the stand, so you can easily take an instant dislike to the later pattern frame.

The undamped rear suspension units look unusual because the compression coil is captive in the centre, between two sliding guides on each side. It doesn’t feel or work any differently to conventional centre-rod suspension units; it just looks a little more interesting.

Switch down the small lever tap at the bottom right of the fuel tank (no reserve), hold the flood button on the carburetter until fuel spits from the vent (no strangler choke), then a firm kick on the pedals and ‘Cappy’ usually fires up first time. If it does die off, it may be necessary to re-flood till the motor runs free, but this is a normal starting quirk. There’s no choke on the carburetter, so repeated flooding is the only option, and keep blipping the throttle till the motor clears to sound strong and responsive.

Clutch in, notch into first, wind on the throttle while feeding back the clutch, and Cappy easily surges away with no need for any pedal assistance—plenty of power!

The motor wants the revs building well up in first before taking the jump up to second (top). Though the power will overcome this loaded phase, it does save labouring the engine, which positively seems to thrive on revs. The two-speed finds its own happy cruising speed between 25 & 30mph, at which the motor is contentedly burbling away at the bottom of the power band. Handfuls of throttle produce a particularly resonant induction roar from the carburetter intake, since the little tin rain shield covering the air filter gauze seems to have a negligible effect in the way of sound baffling qualities. Get the engine hot, and at full steam, top speed in a crouch paced out at 38mph, at which the roaring induction drone seems the most obvious source of noise to the rider, though the escorting pace bike also reported a lively exhaust crackle when following from behind.

Because of the gearing of its top ratio, the two-speed motor runs on the boil all the time, and can pretty much rev out on the flat under favourable conditions. Because of large porting in the cylinder, the Minarelli seems to climb up to an almost explosive rev band that leads the motor into a mechanical howling fury, so to push it over the edge in a kamikaze downhill run should be more than anyone would want to do—the engine will seemingly go on to rev beyond sanity…

Tackling inclines is where the limits of the Minarelli’s two-speed gearbox and its high power band tuning are challenged most. Uphill climbs require a charging technique if you want to be sure of getting up in top gear, since all the Minarelli’s power is developed at revs, so you need to keep the motor buzzing all the time. Against a gradient in top gear, once the revs drop below the power band, you have to cog down to first, which will get the bike up pretty much any incline, but only slowly and involving a lot of revving.

The back pedal rear brake is easily capable of locking up the wheel at any speed, and one discovers the front brake will too, in a desperate moment when a milk float unexpectedly leaps out of a side junction, the driver’s indifferent wave presumably meaning ‘Sorry mate, I didn’t see you’!

The 6V × 15/15W headlamp produces a surprising amount of light for a machine of this age, though the typically deteriorated condition of the Aprilia reflector makes little use of it, while the 6V × 3W festoon bulb taillight is a bit of a glow-worm.

Suspension is undamped both ends, and while the front forks ride the road surface pretty well, the rear shocks are over-sprung and rather too firm, so relay a bit of kidney mashing back to the rider.

Having successfully introduced and sold the ‘Capitano Standard’ model two-speed moped priced at £67–14s–6d, Kerry’s then added to the range in January 1961, by importing the Testi three-speed ‘Economic’ moped. Listed at £79–9s–6d, this model was presented as the ‘Capitano De Luxe Scooterette’ and featured a nacelle headlamp/fork-set, dual seat, and three-speed motor enclosed by engine covers. These additions raised the weight to 107lb (7st 9lb or 48.6kg).

Our unusual and early model De Luxe Scooterette was registered by Cambridgeshire CC in October 1962 and, though somewhat weathered and worn, is still in completely original condition. This features the correct ‘nacelle’ forks, dual seat, long chrome silencer, and its billowing air-scoop engine shield set. Are we transfixed in horror or disbelief! Somehow the styling refreshes memories of bizarre 1950s’ domestic appliances—perhaps you have to hate it to love it?

The three-speed has two push-me/pull-you gear control cables, where the two-speed had only one single gear cable sprung at the selector for self-return. Provided the three-speed twin cable condition is good, then gear selection is just as fine. Starting is the same as the two-speed, but you have to access the carburetter tickle through a tricky little port in the left-hand side panel, and you can’t see when it floods, so it’s common to leave a puddle-of-shame on the floor. The three-speed model features a plastic baffle filter over the carburetter intake that totally silences the draw, so the motor sounds much quieter under load when the throttle is open.

First gear is lower than the two-speed, so it’s easier to make a snappier getaway. Second gear is also lower than the two-speed and there’s no big jump to account between ratios, so the three-speed gearbox proves more useful in mid-range. You really have to turn your left wrist through a big arc to operate the three-speed hand change, then wring round the grip into top—overdrive! This ratio seems higher than the engine wants to pull under normal conditions with its 7:1 compression ratio. Into a headwind or any incline, the three-speed readily fades and you will probably find yourself frustratingly cogging back down to make headway. Pick up a tailwind or downhill and the high gearing gives you a real flyer so you’ll make significant ground against most other period machines under favourable conditions. This three-speed was certainly one of the faster mopeds of its moment in Britain in the early 1960s, our pace bike recording a best of 40mph on the flat in a crouch.

Stretched back along the dual saddle and tucked down to handlebar level on the downhill run, it was difficult to make out quite where the needle was pointing on the silver dial 60mph Huret speedometer, but it was well over in the 3 o’clock quadrant. Our pace bike reported a peak of 45mph, but the speed fell away as we tackled the following incline, and we had to cog back down to second to crest the rise.

An exotic Kerry ‘Gran Prix Sports’ light motor cycle joined the range in 1963, priced at £93–19s–6d. Its engine was exactly the same basic specification as the De Luxe model, same carburetter, same 7:1 compression ratio, same three-speed hand-change gearbox, but featured footrests and a left-hand forward kick-start mechanism instead of the pedal set.

The sports style cycle chassis is where the main difference lies. This comprised a pressed spine braced by duplex tubes welded in from the headstock to underneath the motor. The frame itself is impressively light yet strong, and was made by Jan Junker at Blaricum in Noord Holland, then sent on to Testi for building up.

Overall weight was reduced to 103lb, and trimmed with a lightweight front mudguard, drop handlebars, a top-tank, humpback seat, and sparkling gold frame with red and white paint trim for the fittings—it certainly looked the business!

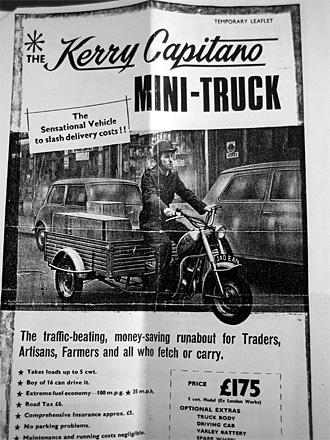

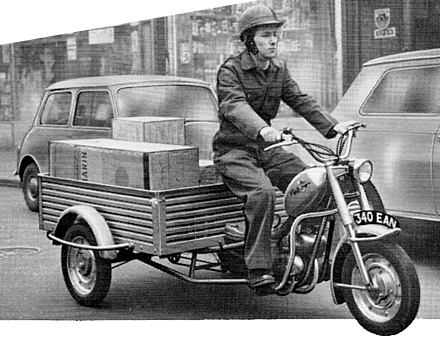

Kerry Mini-Truck delivered to Cheshire CC in 1967

[Photos: David Denny]

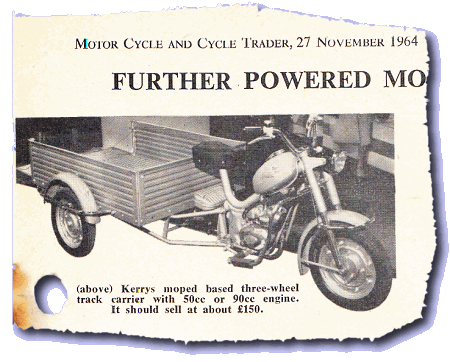

Kerry also advertised a three-speed, fan-cooled ‘Mini-Truck’! This was Testi’s Tri-Porter moped, a style of machines in popular and common light commercial use on the continent, and produced by quite a number of European manufacturers … however, triporteur mopeds never really clicked in the UK, so the Kerry three-wheeler was little more than an interesting and unusual diversion in Britain. When first presented, the Kerry Mini-Truck came as a basic ‘buckboard’ moped with two wheels at the back, but a wide range of accessories allowed conversion pretty much as the customer wished, with a pick-up back, a box carrier van back, and even a cab option for the rider! A standard 49cc and larger fan-cooled engine versions were listed.

An example to the level of sophistication in the enclosed cab was a manually operated windscreen wiper, which required the rider to take a hand off the bars to operate by turning a knob … hmm, different times!

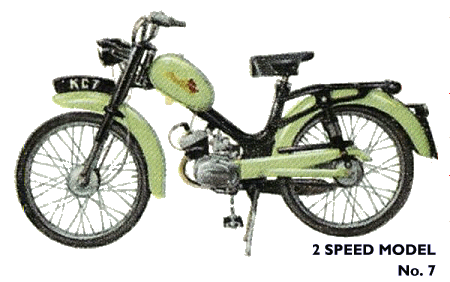

Restyled Capitano models started to be introduced across the range from May 1964 as the formed and fabricated tubular rear frame section gave way to an angular pressing, other detail changes to most of the cycle parts, and galvanised pressed hubs.

The original three-speed De Luxe Scooterette was discontinued in June 1964, with its position in the range seemingly replaced by a new De Luxe two-speed automatic version in the same month. This new Minarelli auto-transmission worked very effectively, proving easier to ride than grappling with the manual gear-change, and the Auto model goes just as well as the manual two-speed models.

Our next testers were two restyled two-speed KC7s. With the restyle came new model designations, mainly just identifying the colour combinations, the red & white three-speed was KC3, red & white two-speed KC4, blue & white two-speed KC5, and apple green & black two-speed KC7. The rear frame-carrier section metal pressing makes sharp handling on its edges when loading the bike on and off the stand, so there’s now no comfortable place for handling the bike since the back underside of the seat also bites into your hand. The rear suspension units switched to a more conventional cylindrical type, petrol tank became more angular, the chain-guard and headlamp brackets changed, and the mounting of the front mudguard to the forks altered. There were many other minor detail changes too, so the restyle actually produced quite a subtly different machine.

The ride was pretty comparable with the earlier two-speed model … maybe the new cylindrical rear shocks give a little more movement, but any real difference is practically imperceptible. The reason all these rear shocks seem so firm is that they appear to be non-adjustable, and are also employed on the three-speed models with dual seat for carrying a passenger, so they’re over-sprung with just the rider aboard.

With two identical apple green & black KC7 models available, we respectively recorded best pace speeds of 36 & 37mph.

Next a restyled three-speed KC3. Note the small pressed toolboxes fitted in the frame forms below the seat on each side, unique to this model. The engine panels are now integrated with leg shields, and Kerry also referred to this machine as a ‘De Luxe Scooterette’. No speedometer is fitted (this was still being offered as an accessory), and the port in the headlamp is blanked, and our bike was run with the leg shields removed for the test run to reduce drag. Our pace bike recorded best downhill in a crouch at 47mph, which took several runs to achieve, as we managed to push the bike slightly faster at each attempt.

With the pull-back style of handlebars, and its dual seat mounting being set a little further back than the single saddle, the additional performance of the three-speed can challenge handling of the cycle chassis and the amount of available grip on the tyres. The dual seat also allows the rider to sit a little further back easily and more comfortably—but the balance of the machine changes, so it becomes appreciably lighter at the front, and readily prone to understeer. Failing to keep this fact in mind, on a frosty corner on the road into Shotley, the author famously crashed this machine quite heavily on the Mince Pie Run in January 2005—when the bike came off somewhat better than the damage to the rider!

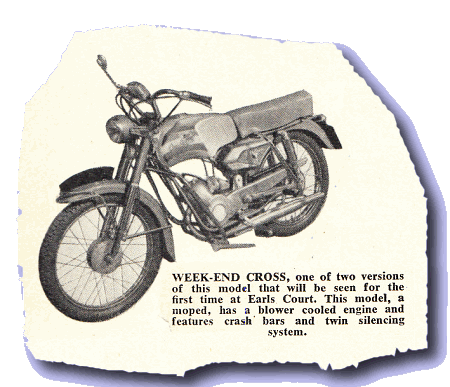

Kerry ‘sampled’ a few other Testi models, like the fan-cooled Weekend Cross in 1964, but there is no real evidence that these ‘tester’ machines were sold in any commercial volumes.

Only sold for three years, the Gran Prix Sports light motor cycle was dropped from the range in October 1965, and a similar three-year run applied to the automatic Capitano as it was discontinued in April 1967. With steadily declining sales, the last two-speed & three-speed models were de-listed in November 1968. The Kerry Capitano had been sold for eight years: a pretty good run in mopedland.

Kerry’s continued selling cycles and their accessory catalogue range through their branches and agents as they had traditionally done, but their market position was coming under increasing pressure from emerging high street competitors. Currys and Halfords particularly were taking their toll on the core business in the cycle sector. Looking increasingly dated, Kerry’s enterprise had run out of fresh ideas, and simply continued doing what it had always done. A once bright crown, its lustre now faded, Kerry’s reign ended in the 1970s as the business was bought out by Partco.

Partco was subsequently acquired by the Unipart/Motorspares Group in May 1999, which continued into the 21st century, until Unipart dramatically collapsed into administration on 24th July 2014.

No buyer for the whole organisation could be found, and of 180 Unipart branches trading as Partco, Unipart, and Express Factors, only 33 survived, with Andrew Page taking 21 retail outlets, and a further 12 going to Parts Alliance.

Presumably somewhere in some forgotten dusty archive file, someone still holds rights to the Kerry brand.