Chapter 1: RSW16 bicycle—From Cycle to

Moped

This tale has to start

with a chap called Alex Moulton, an aircraft engineer, who came

up with designs in the late 1950s to produce small-wheeled

bicycles. He approached Raleigh with the idea, but

negotiations broke down, so he formed his own company as Moulton

Bicycles Ltd and established a factory at Bradford-on-Avon,

to begin building bicycles himself.

This tale has to start

with a chap called Alex Moulton, an aircraft engineer, who came

up with designs in the late 1950s to produce small-wheeled

bicycles. He approached Raleigh with the idea, but

negotiations broke down, so he formed his own company as Moulton

Bicycles Ltd and established a factory at Bradford-on-Avon,

to begin building bicycles himself.

The original Moulton Bicycle was launched in 1962 at the Earls

Court Cycle Show, and presented as a fresh new approach to

cycling design. It proved the right product at the right

time, quickly being adopted as an icon of the

‘swinging-’60s’, and a fashionable mini-bike to

go with mini-skirts and mini cars.

Within a year, Moulton Bicycles had become the second-largest

frame builder in the country, of which Raleigh, as leading

supplier, was now only too aware. Having seen the roaring

success of the Moulton small-wheel cycle, Raleigh now felt the

pressure to come up with another small-wheel cycle design that

wouldn’t infringe any of the Moulton patents. A

Raleigh Small Wheel 16 pre-production model was shown to Alex

Moulton as early as 1964, to go on sale in 1965 as the RSW16, and

differing from the Moulton enough in the critically patent

covered aspects to get away with the design.

Both cycle types had a similar appearance with open-style

frames and carrying capacity.

Moulton employed small diameter wheels of thin section to

reduce frictional resistance, and used suspension to soften its

ride. The Raleigh had a rigid frame, using instead a new

16×2 ‘balloon’ tyre to give a suspension

effect, though at the cost of greater drag and effort to the

rider. The Moulton was more efficient, but the RSW16 came

at a cheaper price and looked the part, so it began to capture

sales back from Moulton.

The RSW16 evolved through a number of changes and different

mark models. Initially introduced in two metallic colours,

green and bronze (red), with a round chrome-plated headlight

mounted on the front mudguard, and calliper rear brake. The

RSW also introduced the twistgrip gear-change selector, mounted

on the right hand bar in the manner of a motor cycle throttle,

with gear position shown by an indicator.

More colour options were added to the range, along with a

stowaway RSW ‘Compact’ version with fold-down

handlebars and break-frame that was humorously derided ‘to

occupy more space in folded form than it did as an assembled

cycle’!

RSWs were further promoted by use of models around ‘The

Village’ in the popular 17-part ‘The Prisoner’

surrealist television series from September 1967 to February

1968. This was filmed at Clough Williams-Ellis’s

mysterious Portmeirion Italianate coastal resort near Porthmadoc

in North Wakes, and featuring Patrick McGoohan as the former

secret agent No.6.

Our featured example is a blue RSW16 MkII version, with tidy

three-speed Sturmey–Archer SB3 rear hub brake, which was

specially designed for the model, and a rectangular headlamp now

mounted on a bracket off the bottom steering head. The

length of the frame head tube was increased over the Mk1.

The lighting set is powered from a front wheel hub-dynamo,

there’s a tidy integral prop stand which makes parking the

bike easy, and the rear bag detaches by a sprung clip at the back

for use as a carrier with two handle straps. No tools are

required for adjustment of the handlebar or saddle height as

these are locked-up by quick release levers.

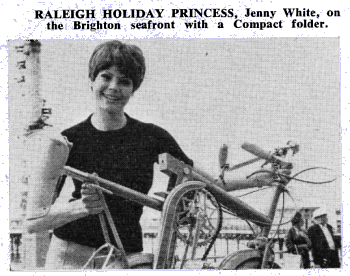

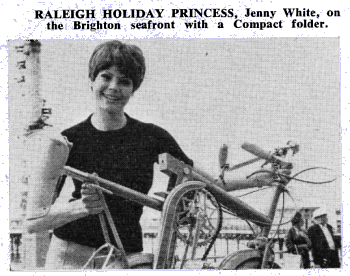

RSW Compact at the 1965 Brighton Show

Max Bygraves with an RSW Compact

For the purposes of our road test we got a fit young fellow

who foolishly volunteered to give his all, while we tracked his

performance from the relaxing comfort of the pace

vehicle…

First gear (a frantic effort) 12mph. Second gear (furious

pedalling) 16mph. Third

gear (giving all and getting red in the face) 22mph.

It was commented by our rider that the RSW felt to be quite

hard work to pedal in comparison to a conventional modern

bicycle, so it looks as if the period criticisms of its cycling

efficiency may well have been justified. It seems more

practical to keep the tyres firmly pumped up, and to use the bike

best at a steady and economical pace, after all, it’s a

trendy shopper—not a racer!

One particularly irritating aspect worthy of observation was

that trying to back the bike with the side stand down would cause

the left-hand pedal to rotate backward, and lock solid against

the stand. The bike would always come to a very firm stop,

invariably resulting in some suitable cursing, then requiring

forward pedal rotation to clear the jam.

Popular success of the RSW16 significantly ate into

Moulton’s sales, driving the new company into financial

difficulties, resulting in Raleigh buying the Moulton business,

then finding itself building both types of small-wheeled

bicycles.

Raleigh continued production of the RSW until 1974, by which

time sales of small-wheeled bicycles had slowed to a

trickle—the trendy fashion had fizzled out! The

‘16’ was discontinued after reportedly selling some

100,000 models over nine years, but it’s slightly larger

and more popular RSW20 version endured well into the 1980s.

A new Alex Moulton company continues to manufacture and sell

specialist small-wheeled cycles today.

Chapter 2: Raleigh Wisp—The Chicken or the

Egg?

Even before the introduction of the

RSW16, somebody at Raleigh had also come up with the idea to

motorise the new small wheel bicycle by fitment of an engine that

was already being licensed from Motobécane, as had been

introduced in the RM4 from February 1961, and continued into the

RM6 Runabout from May 1963.

The project to produce a motorised version of the RSW16

bicycle was coded RM7, and we can get some idea when this started

because the engine specification was entered as 1.4bhp, as taken from the continuous-fin,

6.5:1 compression motor used in the RM6 at the time, and up to

November 1965 when the early engine would be wholly succeeded by

the new replacement split-fin 7.5:1 compression, 1.7bhp engine.

The RM7 code was allocated to the motorised RSW16 project

before or at the same time as the RM8 Runabout project was

issued. The RM7 model required somewhat more involved

development than the simple RM8 Runabout, which was announced and

introduced in December 1963, so the RM7 project must also have

been commissioned in 1963.

It’s easy to presume that the RM7 may have simply

involved bolting an engine into the RSW16 cycle frame, but the

physical mechanics don’t quite work like that. The

RM7 looked very similar to the bicycle, but actually employed a

completely different frame with reinforced sections at all its

joints.

Development of the RM7 was taking much longer than expected,

as the RM9 was introduced in April 1964, and the RM12 Sports-50

from June 1965, then the RM11 Super Tourist from January

1966.

The earliest ‘D’-registered factory

prototype RM7s were completed and running around on

pre-production road tests from summer 1966 (JAU 70D), and

early ‘E’-registered examples (after August 1966), at

which time the models were already branded by a Wisp graphic.

The earliest ‘D’-registered factory

prototype RM7s were completed and running around on

pre-production road tests from summer 1966 (JAU 70D), and

early ‘E’-registered examples (after August 1966), at

which time the models were already branded by a Wisp graphic.

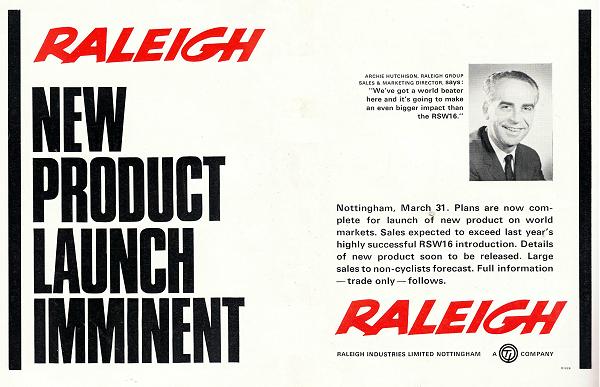

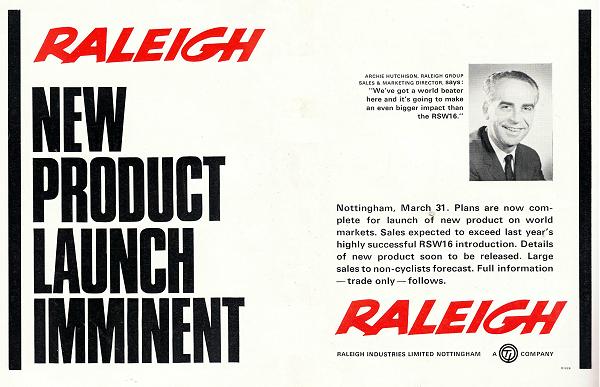

The new moped was introduced on April 14th 1967 priced at 57

guineas (£59–17s–0d), but Raleigh never

officially referenced back to the original RM7 project

designation, and only ever called the machine

‘Wisp’.

The launch promotions and publicity material for the Wisp were

particularly iconic, with a ‘symbol of innovation’

sculpture piece commissioned by Raleigh Industries for

‘Wisp’, incorporating the letters R and W.

There was a classically famous photo-shoot with the fashion model

‘Twiggy’ (Lesley Hornby) riding a Wisp. A

fantastic 16-page colour printed sales booklet that is now

considered as highly collectable literature, and accompanied by a

series of punchy advertisements in newspapers, magazines, and the

motor cycling press. A rhinestone studded Wisp was

decorated to tour the circuit of promotional events, and

Pathé Newsreel filmed two lady models riding Wisps at

Kenley RAF Station, Surrey

(2½ minute video and stills available).

With all the old continuous-fin 6.5:1 compression,

1.4bhp engines finally

used up back in November 1965, production Wisps in 1967 were

fitted with the newer replacement split-fin, 7.5:1 compression

engine rated 1.7bhp.

Published specification data for Wisp however, mistakenly

returned the original 1.4bhp rated information, which was

subsequently interpreted that its performance had been restricted

by fitment of the special inlet manifold cast by Raleigh to

maintain the carb float bowl level due to Wisps greater

inclination engine mounting.

Though the special Wisp manifold reduces this inlet bore to

3/8" (9.52mm) from the AR10mm

Gurtner carburettor, this tiny change certainly wouldn’t

wipe off 0.3bhp from a

1.7bhp motor.

The Wisp was mainly only produced in two colours, Fiesta Blue

& Spanish Gold, though the rhinestone studded Wisp was

finished for marketing promotional purposes, and some white ones

were reportedly produced later in the run, but we’ve never

seen any.

Our

first tester, registered on 27th September 1967 is a Fiesta Blue

Wisp trimmed with white cables, saddle cover, carrier box, and

handle grips, showing frame number 016420, and fitted with

original specification 44-tooth rear sprocket.

Our

first tester, registered on 27th September 1967 is a Fiesta Blue

Wisp trimmed with white cables, saddle cover, carrier box, and

handle grips, showing frame number 016420, and fitted with

original specification 44-tooth rear sprocket.

To start Wisp, there’s a little petrol tap

‘key’ that inserts through a hole in the left-hand

engine cover just below the petrol tank. Though the

‘key’ is removable, that function is only intended to

enable the cover to be removed, which wouldn’t be possible

with the ‘key’ permanently fixed in place as part of

the fuel tap. It isn’t really practical to use this

as any security device to disable the fuel supply since it

isn’t so easy to relocate the extended shaft back into the

petrol tap socket, and requires rotation of the flat on the shaft

to feel into alignment with the flat in the tap, then push in to

click home.

Turning the key clockwise through 90° turns on the main

tank, and a further 90° clockwise to the stop gives reserve

supply.

Turn the throttle twistgrip forward to decompress, pull in the

trigger choke under the left-hand bar, firmly kick the pedal to

spin the motor and twist the throttle open at the same

time. If you’re lucky the motor might catch. If

not, then pedal up the road (we don’t really recommend

pedal-starting on the stand since this is usually what’s

responsible for lots of ruined moped centre stands).

Apart from an initial flat-spot when the clutch shoes engage

the drive, acceleration from a standstill proved quite

reasonable, though it was very quickly obvious that this was

because the bike appears dramatically under-geared, and achieving

only 22mph (paced) along the

flat. The bike further slowed to 19mph against a light uphill gradient,

which rather surprised us since we thought the low drive ratio

would allow it to climb the incline without dropping any pace,

but not so—never underestimate the power of gravity!

Downhill run 25mph, but this was ridiculously

over-revving. Vibrations through the seat were akin to

receiving an electric shock, and were so uncomfortable that you

really didn’t want to be sitting on the sprung ‘super

comfort’ foam padded-saddle. Within a few hundred

yards at this speed, it felt as if you’d been injected with

anaesthetic! This was a level of vibration that crossed the

pain threshold. No wonder it’s common to find so many

cracked number plates and mudguards on Wisps!

Downhill run 25mph, but this was ridiculously

over-revving. Vibrations through the seat were akin to

receiving an electric shock, and were so uncomfortable that you

really didn’t want to be sitting on the sprung ‘super

comfort’ foam padded-saddle. Within a few hundred

yards at this speed, it felt as if you’d been injected with

anaesthetic! This was a level of vibration that crossed the

pain threshold. No wonder it’s common to find so many

cracked number plates and mudguards on Wisps!

The riding experience wasn’t quite as claimed in the

sales booklet, which stated ‘Beats 25mph without any fuss. Feels great

all the time’—that’ll be artistic license

then.

In January 1968 the rear sprocket was changed to 36-tooth to

address dealer and customer complaints of over-revving causing

engine failure, and excessive vibration. The Wisp frame was

also reportedly modified at this time with an increased angle on

the head tube and the handlebars altered to suit the new

angle.

Considering that the rear sprocket change raised the final

drive ratio by over 18%, it’s easy to appreciate how

dramatically under-geared the early Wisps were with the original

44-tooth sprocket.

The 44-tooth rear sprocket was initially fitted,

simply because it was the smallest sprocket available from

Motobécane to fit the Atom hub—but it very clearly

wasn’t at all suitable for the tiny Wisp wheels, and why

Raleigh even went ahead with putting out production bikes with

such a dramatically low drive ratio that could so easily over-rev

their engines, was a total mystery.

The 44-tooth rear sprocket was initially fitted,

simply because it was the smallest sprocket available from

Motobécane to fit the Atom hub—but it very clearly

wasn’t at all suitable for the tiny Wisp wheels, and why

Raleigh even went ahead with putting out production bikes with

such a dramatically low drive ratio that could so easily over-rev

their engines, was a total mystery.

Raleigh had to make the 36-tooth sprocket themselves as a

special.

Considering that the RM6 Runabout, fitted with the same engine

and using the same 44-tooth rear sprocket, drives 23" diameter

wheels to the Wisp’s 16", then the original Wisp seemed to

be running a 30.5% lower drive ratio!

Our

second tester is a Spanish Gold Wisp, which colour scheme was

trimmed with the same white cables, though black saddle cover,

carrier box, & handle grips. Fitted with the smaller

36-tooth rear sprocket and registered in 1968, this would appear

to be a ‘new specification’ manufacture, but with

frame number 012376, this appears to be a lower serial than our

first 44-tooth tester, so we’re a little confused how

Raleigh’s frame numbering was working on these

machines? Our conclusion is that this bike might have been

retrospectively fitted with the smaller 36-tooth sprocket to

resolve its revving and vibration issues.

Our

second tester is a Spanish Gold Wisp, which colour scheme was

trimmed with the same white cables, though black saddle cover,

carrier box, & handle grips. Fitted with the smaller

36-tooth rear sprocket and registered in 1968, this would appear

to be a ‘new specification’ manufacture, but with

frame number 012376, this appears to be a lower serial than our

first 44-tooth tester, so we’re a little confused how

Raleigh’s frame numbering was working on these

machines? Our conclusion is that this bike might have been

retrospectively fitted with the smaller 36-tooth sprocket to

resolve its revving and vibration issues.

Both our feature bikes mounted the ‘super comfort’

pad-saddle, which hinges from the front, with a shock absorbing

compression spring between the back of the base and the saddle

mounting frame clamped to the seat post.

Another un-sprung version of the ‘super comfort’

pad-saddle was also sold as an accessory for Raleigh RM6, RM8,

and RM9

Rather than simply being mounted ‘flat’ as the

un-sprung ‘super comfort’ pad-saddle, insertion of

the spring requires the saddle to be pitched at a suitable

forward angle so it can comfortably sit flat under compression of

the spring with the rider mounted.

Starting procedure was exactly the same as the earlier model,

and pulling off from a standstill, you notice the gearing

difference straight away. There’s now a big flat-spot

as the clutch shoes engage the drive, and the motor labours hard

against the higher ratio. It’s easy to imagine that

there might now be some circumstances where the bike might

appreciate some pedal assistance in pulling away.

Acceleration is obviously slowed by the ratio change, but it

does make a huge difference to the Wisp. The engine revs

are much more leisurely, considerably reducing vibration, and

making the whole riding experience a lot more comfortable for mid

range cruising.

While the final drive gearing has been raised by over 18%,

this doesn’t seem to translate directly into 18% more speed

for our test mount, which burbles along quite happily, but seems

too docile to achieve anywhere near the kind of screaming revs

our earlier under-geared example achieved. Possibly our

brief test run being its first outing following 25 years in the

back of a lock-up garage wasn’t enough to clear the

cobwebs, but the pace results were a little disappointing.

It just didn’t seem quite ready to get-up-and-go.

23mph along the

flat, dropping back to 19 on uphill climb, and 25 downhill.

Little difference really to the earlier low-ratio version, but a

whole lot more comfortable to ride.

23mph along the

flat, dropping back to 19 on uphill climb, and 25 downhill.

Little difference really to the earlier low-ratio version, but a

whole lot more comfortable to ride.

Theoretically achieving the same revs should have expected

26mph along the flat and 29 downhill, but this example proved a

little off the pace for its top speed.

At the end of June 1969, Raleigh’s owners Tube

Investments delivered the bombshell news to its employees of the

Motorised Division that they were all on three months’

notice of redundancy, and that all powered products were to be

dropped. Introduced 14th April 1967, Wisp production

officially ended in September 1969, along with the RM5

Supermatic, RM8 Automatic MkII, RM9 Ultramatic, and RM9+1

(RM10).

With a revised frame numbering system, only the faithful RM6

Runabout soldiered on to burn off stocks, until January 1971,

when the last Raleigh moped officially disappeared from the

lists.

After some four years in development, the iconic Wisp had been

in production for a mere 2½ years.

So what came first, the chicken or the egg? Neither

actually—The RSW16 bicycle and RM7 Wisp were conceived at

exactly the same time, somewhere back in 1963 when Raleigh were

deciding on a way to reply to Alex Moulton’s small-wheel

bicycle. It’s just that the RSW16 bicycle was

completed for sale first in 1965, while the Wisp moped required

more development, so consequently wasn’t launched until

1967.

Next—An ancient name, returning back from the

pioneering dawn of motor cycling, though strangely, one of our

most difficult research projects to track, since so little ever

seems to have been published about them!

It’s been particularly hard piecing together all the

various fragments of related history scattered over an incredible

137 years. This project research file was actually started

in April 2006, way back before we’d even started

IceniCAM!

You want a clue what the bike may be? Who takes 46 years

to build a moped? Return of the New

King.

This article appeared in the January 2016 Iceni

CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2016

M Daniels.]

Making The Chicken or the Egg?

The concept and structure of our

Raleigh Wisp article was formulated quite some time back, and was

planned with the intention of creating a definitive and fully

comprehensive production.

Since the Wisp technical specification was revised after its

first season to address the over-revving and subsequent engine

failure & vibration issues, we would be needing standard

models in each configuration.

The Wisp was only sold in the two metallic colours of Fiesta

Blue and Spanish Gold, so we would also ideally be wanting two

bikes, both in original factory finishes for the photoshoot.

Being primed with a reflective aluminium base coat, then

coloured with a translucent topcoat, makes the original metallic

finishes of the Wisp particularly difficult to reproduce

properly, and most seem to become repainted in either a standard

block blue or some proprietary gold, which rarely look anything

like the original finish.

Since presenting the correct colours was considered so

important for the photoshoots, we decided that only good original

paintwork would suffice, which instantly ruled out a lot of the

available examples.

Our first and most promising opportunity came in summer 2012

when the workshops bought in a brace of bikes from Hemel

Hempstead, as a ‘his & hers’: a 1964 80cc Suzuki

K10 and a 1967 Fiesta Blue Raleigh Wisp in early 44-tooth

configuration.

Of the two bikes, the Raleigh Wisp was actually processed

first and, as an obviously low mileage machine, restored to

fantastic original condition. This represented a great

example to get our article started, but the road test proved an

horrendous experience, with screaming revs and shattering

vibration due to the original undergeared 44-tooth low drive

ratio.

You instantly appreciated how Wisps’ first customers

must have felt—it was dreadful!

Having got the blue Wisp road test & photoshoot completed

in August 2012, the bike was very quickly sold on.

The workshops then set about restoring the Suzuki K10, which

was subsequently completed for RT&PS in April 2013, but

didn’t appear in the Thin End of the Wedge article

until in January 2015.

The Wisp project had meanwhile gone into mothballs awaiting

the availability of a later specification Spanish Gold example

with 36-tooth rear sprocket. You’d think this should

be a fairly easy demand to satisfy, since there are lots of Wisps

around, but it seems funny how you can never find exactly what

you want when you’re after something so specific.

It wasn’t until August 2014 when we were at the West

Anglian section’s Shuttleworth Shuffle event based at

Moggerhanger village hall, that we diverted to the outskirts of

Milton Keynes after the event, to collect another 1969 Wisp that

the workshops had done a deal to buy in.

This machine proved to be the correct original Spanish Gold

colour and later 36-tooth specification we were looking

for—but what a derelict! 25 years storage in the back

of a lock-up garage had certainly taken its toll.

This was going to take an awful lot of fixing …

there was a major worklist for this bike and the rotted petrol

tank had to be replaced & repainted.

It was July 2015 before this Wisp rolled out of the workshops

for RT&PS,

and again, our second Wisp was shortly sold on after its purpose

had been fulfilled.

Meanwhile, towards the last months of 2014, the workshops had

also acquired a promising and obviously minimal-use

RSW16 MkII bicycle that required some work and new tyres,

but was clearly too good not to save—so now we had the

opportunity to add a third element to our Wisp feature.

The RSW16 was fixed up for RT&PS in January 2015,

then shortly sold on to the same buyer of our Kieft KS50 from the

Racing Heritage feature in our last

edition of October 2015. When Norman Crawford bought the

Kieft and RSW16, he also made a donation to sponsor the KS50

article, but we’d ‘misplaced’ his details at

the crucial moment when the credits were being attached, so

Norman ended up sponsoring his RSW16 instead.

All articles are initiated as individual text files on

RT&PSs, so

the Wisp file started from notes on the Fiesta Blue bike, then

the Spanish Gold notes were added on later, and the file

subsequently collated with related research notes from

there. Much of this text was developed and written up while

Danny was in Malta during September 2015; in fact most of

IceniCAM edition 36 was drafted over this week in the

Mediterranean, so we were actually well ahead of the game for a

change this time.

The RSW16 file was separately developed from its own

individual file, so by the time we’d decided to present the

RSW and Wisp features in the same article, they’d already

evolved as separate entities. Instead of engaging in a

complete re-write to blend both text files together, it was

decided to produce the article in two distinct chapters.

This unusual structure however, seemed to work out quite

naturally for this particular feature, since Raleigh launched the

bicycle so quickly in 1965, while the RM7 motorised version

wasn’t completed until a whole two years later.

Not until all the various Raleigh project timings were

collated, could it really be appreciated that the RSW16 bicycle

and Wisp were actually initiated at the same time in 1963, while

everyone had always presumed that the Wisp had evolved later as a

development of the bicycle.

Several titles for the RSW/Wisp article were toyed with, but

From Cycle to Moped & The Chicken or the Egg? seemed most appropriate for

the time honoured question of which came first?

Raleigh marque specialist Les Gobbett has had a long-standing

sponsorship credit lodged with us for another Raleigh article,

and it’s certainly taken a while to work this Wisp feature

to completion: 3½ years in fact! We felt it was

particularly important being patient enough to get all the

article details absolutely right in the end, to finally present

such a worthwhile and definitive reference piece about the Wisp

moped.

This tale has to start

with a chap called Alex Moulton, an aircraft engineer, who came

up with designs in the late 1950s to produce small-wheeled

bicycles. He approached Raleigh with the idea, but

negotiations broke down, so he formed his own company as Moulton

Bicycles Ltd and established a factory at Bradford-on-Avon,

to begin building bicycles himself.

This tale has to start

with a chap called Alex Moulton, an aircraft engineer, who came

up with designs in the late 1950s to produce small-wheeled

bicycles. He approached Raleigh with the idea, but

negotiations broke down, so he formed his own company as Moulton

Bicycles Ltd and established a factory at Bradford-on-Avon,

to begin building bicycles himself.

The earliest ‘D’-registered factory

prototype RM7s were completed and running around on

pre-production road tests from summer 1966 (JAU 70D), and

early ‘E’-registered examples (after August 1966), at

which time the models were already branded by a Wisp graphic.

The earliest ‘D’-registered factory

prototype RM7s were completed and running around on

pre-production road tests from summer 1966 (JAU 70D), and

early ‘E’-registered examples (after August 1966), at

which time the models were already branded by a Wisp graphic. Our

first tester, registered on 27th September 1967 is a Fiesta Blue

Wisp trimmed with white cables, saddle cover, carrier box, and

handle grips, showing frame number 016420, and fitted with

original specification 44-tooth rear sprocket.

Our

first tester, registered on 27th September 1967 is a Fiesta Blue

Wisp trimmed with white cables, saddle cover, carrier box, and

handle grips, showing frame number 016420, and fitted with

original specification 44-tooth rear sprocket. Downhill run 25mph, but this was ridiculously

over-revving. Vibrations through the seat were akin to

receiving an electric shock, and were so uncomfortable that you

really didn’t want to be sitting on the sprung ‘super

comfort’ foam padded-saddle. Within a few hundred

yards at this speed, it felt as if you’d been injected with

anaesthetic! This was a level of vibration that crossed the

pain threshold. No wonder it’s common to find so many

cracked number plates and mudguards on Wisps!

Downhill run 25mph, but this was ridiculously

over-revving. Vibrations through the seat were akin to

receiving an electric shock, and were so uncomfortable that you

really didn’t want to be sitting on the sprung ‘super

comfort’ foam padded-saddle. Within a few hundred

yards at this speed, it felt as if you’d been injected with

anaesthetic! This was a level of vibration that crossed the

pain threshold. No wonder it’s common to find so many

cracked number plates and mudguards on Wisps! The 44-tooth rear sprocket was initially fitted,

simply because it was the smallest sprocket available from

Motobécane to fit the Atom hub—but it very clearly

wasn’t at all suitable for the tiny Wisp wheels, and why

Raleigh even went ahead with putting out production bikes with

such a dramatically low drive ratio that could so easily over-rev

their engines, was a total mystery.

The 44-tooth rear sprocket was initially fitted,

simply because it was the smallest sprocket available from

Motobécane to fit the Atom hub—but it very clearly

wasn’t at all suitable for the tiny Wisp wheels, and why

Raleigh even went ahead with putting out production bikes with

such a dramatically low drive ratio that could so easily over-rev

their engines, was a total mystery. Our

second tester is a Spanish Gold Wisp, which colour scheme was

trimmed with the same white cables, though black saddle cover,

carrier box, & handle grips. Fitted with the smaller

36-tooth rear sprocket and registered in 1968, this would appear

to be a ‘new specification’ manufacture, but with

frame number 012376, this appears to be a lower serial than our

first 44-tooth tester, so we’re a little confused how

Raleigh’s frame numbering was working on these

machines? Our conclusion is that this bike might have been

retrospectively fitted with the smaller 36-tooth sprocket to

resolve its revving and vibration issues.

Our

second tester is a Spanish Gold Wisp, which colour scheme was

trimmed with the same white cables, though black saddle cover,

carrier box, & handle grips. Fitted with the smaller

36-tooth rear sprocket and registered in 1968, this would appear

to be a ‘new specification’ manufacture, but with

frame number 012376, this appears to be a lower serial than our

first 44-tooth tester, so we’re a little confused how

Raleigh’s frame numbering was working on these

machines? Our conclusion is that this bike might have been

retrospectively fitted with the smaller 36-tooth sprocket to

resolve its revving and vibration issues. 23mph along the

flat, dropping back to 19 on uphill climb, and 25 downhill.

Little difference really to the earlier low-ratio version, but a

whole lot more comfortable to ride.

23mph along the

flat, dropping back to 19 on uphill climb, and 25 downhill.

Little difference really to the earlier low-ratio version, but a

whole lot more comfortable to ride.