The Phillips Company was formally started in 1896, making cycle pedals and brakes for the cycle trade from Newhall Street, Birmingham. The original partnership of the firm consisted of John Alfred Phillips (born 1866 in Coventry), Ernst Wilhelm Bohle (born 1872 in Bergneustadt, Germany), and Henry Charles Church (born 1871 in Birmingham).

Tube Companies

At the end of the 19th century there was a huge demand for weldless tubes with the result that many companies were formed to meet the demand—so many that, by the turn of the century, more tubing was being made than manufacturing industry needed. There was a flurry of bankruptcies, recapitalizations, mergers, etc, that resulted in many companies bearing similar names and it becomes difficult to unpick them all. Although Weldless Tubes Ltd became Tubes Ltd it is not to be confused with The Weldless Steel Tube Co (often called the ‘Old Weldless’). In the early years of the 20th century, the ‘Old Weldless’ and Tubes Ltd were the main rivals and it is estimated that either one of them could supply enough tube to satisfy the entire British cycle industry. Tubes Ltd was the loser in the ensuing price war and the company collapsed in 1906; meanwhile the ‘Old Weldless’ suffered much reduced profits but, nevertheless, continued relatively unscathed … for a while.

Arthur Chamberlain salvaged enough from the wreckage of Tubes Ltd to reform the company and, after World War I, form Tube Investments which, in turn, would acquire the ‘Old Weldless’.

1905 Phillips advert

The Midland Gun Co had occupied number 77 Bath Street, Birmingham as the ‘Demon Gun Works’ from 1888 to 1902, after which Phillips seemed to move into these premises, and was posting trade adverts for its cycle fittings from this address by June 1904.

In 1907, J A Phillips & Co, bought the Credenda Works at Bridge Street, Smethwick, giving up its Birmingham premises. The Credenda Works site had previously been occupied by Birmingham Plate Glass Co, before being converted into a tube mill by the newly formed Credenda Seamless Tube Co in 1889. This business was bought out by Star Tube Co in 1896, which became part of Weldless Tubes Ltd in 1897, making tubes for cycle, marine, boiler, boring, mining, and gun carriage applications. Later called Tubes Ltd, the consortium comprising Climax, Credenda, and Star Tube works was virtually broke by the end of 1905. The tube works closed in 1906 and its Bridge Street premises was offered for sale in September 1906, where the plant included tube rolling mills and 16 steam engines.

So the Credenda works was purchased by Phillips in 1907, with presumably much of the dedicated tube making machinery already in place, which would certainly have been a huge advantage to a firm making cycle components, and later complete bicycles.

The previous Bath Street premises were probably around 15,000 square feet in area, while the Credenda Works comprised a long narrow site of some 8½ acres running west to east, with about one third at the eastern end still being undeveloped. It had an internal rail system shared with neighbours Kingston Metal Works, and giving access to the LNWR’s Stour Valley rail line, while to the south the site was bounded by the Birmingham Canal Navigations Feeder Arm, where the Bridge Street site had its own wharf: so excellent transport connections. The main works building provided some 90,000 square feet of space with ancillary buildings adding about the same again, making around 180,000 square feet of factory capacity.

J A Phillips left the partnership in July 1910, his father Henry Phillips died on 20th August 1910, and John A Phillips married Agnes Ellen Clifton at St Peters Church, Bournemouth, Hampshire in the first quarter of 1911, which might account why he is not found in the 1911 census as he was possibly travelling abroad following the wedding, though he still retained a minority shareholding in the business into 1914.

After the dissolution of the partnership there seemed to be a determined effort from Bohle and Church to promote the company’s products. In 1910 the company had a stand at the Stanley Show held at the Royal Agricultural Hall, Islington, London, from 11 to 19 November and, in the same year, it exhibited at the Cycle and Motor Cycle Show at Olympia, London. The range of products included handlebars, brakes, pedals, reflectors, roller skates, and hubs (newly added in 1910). By 4th August 1914, when Great Britain declared war on Germany, Phillips was employing 1,000 people.

Phillips‘s mark on a

1915 BSA military bicycle

Photo: V-CC Library

Although it exported bicycles, Phillips did not sell complete bicycles in Britain, just components, but there are indications that Phillips had supplied complete cycles to the military from 1908. A Phillips ‘Folding General Service’ military folding bicycle was in production in 1910, and there are reports of Phillips bicycles being supplied to the Birmingham City Battalion in 1914. Cycling military history states that Mk I to Mk IV military bicycles were all supplied by BSA, but it seems likely they must have contracted out to other companies.

The Credenda Works was commandeered by the War Office for the making of munitions, and contracts were also received to supply the Government with cycle components; the Army Cyclist Corps was formed in November 1914 with one Cyclist Company for each Division, their role being reconnaissance and communications (message taking). As there were 75 Divisions, and a Company was about 250 men, this equates to 18,750 bicycles.

These contributions to the war effort were, however, to be halted: the Birmingham Mail headline of Monday 14 December 1914 announced ‘Big fire at Smethwick—1,000 workpeople thrown out of employment—Credenda Works gutted’. The fire had broken out in the enamelling shop, where enamelled items were baked in ovens, but the following fire then swept through the entire premises. The newspaper reported ‘From the Bridge Street entrance of the works along to the polishing shop, a distance of some hundreds of yards, only the outer walls remained. Inside, the iron girders and machinery were twisted out of all recognition … The shops involved were the automatic machine shop, the press, handle-bar, pedal, and frame workshops, the rubber stores and general warehouses. In the latter there was a large quantity of finished material, the whole of which, of course, was destroyed … The extent of the damage cannot yet be ascertained, but it is certain to reach a very big figure as not only the whole of the machinery, stock and materials, but also the works themselves have been destroyed.’

1936 advert for Phillips

cycle components

Under normal circumstances it could have taken several years to get the plant operating again after such a devastating fire, though this process would have been accelerated by wartime expediency. As Credenda Works was rebuilt, re-equipped, and did resume trading, one must assume that this was completed at some point, but must have compromised production for a period.

As if the fire wasn’t enough, just a few days after the fire, the company Directors and staff found themselves being prosecuted under the ‘Trading with the Enemy Act’; The Birmingham Mail issue of Thursday 17 December 1914, reported: ‘There were altogether 16 summonses, six against the firm, four against Ernest William Bohle, Credenda Works and Otto Hesmer, of the same address, and against Henry Charles Church whose address was also given as Credenda Works.’

It was alleged that in August and September of 1914 they had ‘unlawfully’ obtained 20,000 pairs of handlebar grips from Germany via Messrs Adler who had premises in England, France, and Amsterdam. The final hearing was reported in the Birmingham Daily Post on Friday 15 January 1915 when it was revealed that Otto Hesmer took the whole responsibility for the transactions; following legal arguments relating to case law however, the summonses were withdrawn by the Crown.

1919, and Tube Investments was formed as a holding company combining the seamless steel tube businesses of Tubes Ltd, New Credenda Tube, Accles & Pollock, and Simplex, based in Abingdon, Oxfordshire, and listed on the London Stock Exchange.

It was reported in The Times of 9 December 1920 that Arthur Chamberlain, chairman of TI, told the first AGM that ‘Phillips, a maker of bicycle parts, had been acquired since the amalgamation in 1919’. Tube investments further acquired Reynolds Tube in 1928.

During World War II, Phillips primarily switched to munitions work, producing vast quantities of shells (89 million!), armour piercing tips, grenades, land mines, aircraft parts, and again made complete bicycles for the military, particularly assembling Mk.V Military Roadster cycles with conventional roller lever brakes.

1947 advert for complete Phillips bicycles

In 1946 TI bought Swallow Coachbuilding (as founders of Jaguar Cars), but then only making sidecars at Walsall Airport, and also acquired Hercules Cycles of Coventry, once the largest manufacturer of bicycles in the world. This year, for the first time, Phillips sold complete bicycles in Britain.

In 1952, there now became two Phillips companies, both registered from the same address of Credenda Works, Smethwick, Birmingham. J A Phillips & Co Ltd was the original company who manufactured all the cycle related components, and the new Phillips Cycles Ltd, which was registered to cover assembly and sale of cycles, though commercial civilian bicycles were being made and sold before this date.

During the 1950s and due to increasing frame and fork failures of standard cycles fitted with cyclemotor kits, several manufacturers started producing special reinforced frames for mounting cyclemotor engines. Among them were BSA (including New Hudson and Sunbeam variants), Elswick, Mercury, Phillips, Triumph, and Sun.

In the Coronation year of 1953 Phillips launched an impressive range of 40 cycles including touring and sports models, children’s bicycles and tricycles, trade-bikes, and heavy duty machines designed to accommodate the motorised rear wheel. These were available as Gents’ ‘diamond’ or Ladies’ style ‘open’ heavy-duty cycle frames, with options of drum or rim brakes for the front wheel, and without the rear wheel if a Cyclemaster motor-wheel was intended to be installed.

Progressing on to supplying a complete machine, the Phillips ‘Motorised Cycle’ with a fitted German Rex single-speed, manual clutched engine and braced rigid fork was introduced in October 1954 at £49–15s (inc. purchase tax), but by September of 1955 the same machine was being listed for £55–12s–10d, reflecting quite a high annual inflation rate running around 11% at this time.

The following month brought a Mk 2 Motorised Cycle fitted with a telescopic fork set, having simple greased springing for suspension, with no damping function. The P36X designation and £55–12s–10d price tag remained the same for the new sprung-fork model, which succeeded the original rigid Mk 1.

The list price of the P36X Motorised Cycle rose to £57–17s–11d in 1956, and though the Gadabout moped was costing over £11–7s more, it did seem to be attracting better sales.

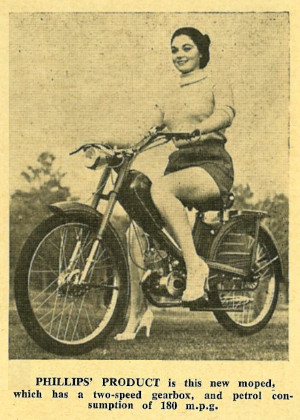

Leila Williams posed on the

Gadabout for the 1955 Show publicity

Another of the 1955 publicity photos.

Simply having the cheapest purchase price was seemingly no longer the prime factor to consider in a transport purchase. The post-war years of austerity were coming to an end, and now that the buying public was acquiring more disposable income they were choosing to buy better-built machines, so favour for a cyclemotor was swinging toward the moped.

Phillips introduced its new P39 Rex-powered two-speed Gadabout moped at the 12 November 1955 Earls Court Motor Cycle Show, and employed the same design of telescopic fork as the Motorised Cycle.

As the first sales season was about to start on 31 March 1956, the posted base price was 68 guineas (or 70 guineas with a fitted speedo).

The logo on the clutch case as an imperial crown, but no name badge was pinned to the mag cover, which was simply left blank. Phillips didn’t seem to want to advertise that it was fitting a German Rex engine.

Lots of features were markedly different about the earliest P39 Gadabouts in comparison to the later models. Most of the early bike components comprised German made Rex components, which Phillips would progressively phase out and replace with English manufactured equivalents.

With the first P39 version, it’s probably simpler to start with the few British parts: the chrome plated half-width front hub is British Hub Co with a balancer flange laced into a Dunlop Westwood pattern rim, with a matching rim laced on the rear unknown continental alloy full-width hub, and fitted with Dunlop 2.00 × 19 tyres. The rear lamp unit is an early version of the Wipac S446 (which had to be fitted to be UK compliant), the saddle was British market, and Phillips applied tank transfers and a headstock badge.

The German content in these early models was literally everything else, the frame, mudguards, chain guards, rear hub. Rex made the original seven-pint ‘bubble’ petrol tank matched with a longer alloy casting to trim the frame down to the seat post, which would become swapped for a larger ten-pint ‘teardrop’ tank by Phillips in October 1956, with shortened alloy casting to trim the frame down to the seat post. The Rex upper and lower chain guards were both identified by a swage line that Phillips deleted from their own equivalents. The Hella aluminised steel headlamp and unique switch would subsequently be replaced by Phillips’s own Excelite headlamp and Miller switch. The Bosch mag-set was changed to a Miller FW17. The German Magura throttle and hand-change components were destined to change to Amal, and it’s unusual to find such a mostly original and early P39 example as this to illustrate as a comparison.

Our bike’s lower chain-guard is a custom aluminium fabrication because the original pressed-steel component was absent, and was created to blend with the engine and mag cover—we think it looks great!

Rex quoted the engine specification as 40mm bore × 39.5mm stroke for 2.1bhp@6,000rpm with 6.8:1 compression ratio and a 12mm Pallas carburettor. The original standard fitted front sprocket was 12-tooth, and a period Power and Pedal road test in June 1956 reported a max of 32 mph, but our bike has been geared up to 13-tooth (7.7%), because the motor felt as if it could pull this increase and offer a slightly higher cruising speed.

The Pallas was an early spray-tube carburettor carried over from the earlier Rex single-speed motorised cycle engines, but fitment onto the two-speed moped exposed its performance weakness: flat spots! In first gear the flat spot is less noticeable due to the lower ratio, but switch into second, open the throttle, then wait and wait as the motor struggles to find the carburation to claw up more speed. If you run up the revs in first, you can mitigate the flat spot effect, but that’s not nice way to ride a torquey motor like the Rex.

The situation might be exacerbated by the original Rex rubber tube connecting the carb intake (which is long obsolete) having perished and rotted away, which may compromise draw through the carb to the frame. Swapping out the Pallas 50 & 52 main jets we have seems to have little effect, and though a 55 is listed, we don’t have any—but we do have jet drills, so we open one up to 55, and it does seem to somewhat negate the flat spot effect and slightly improve the performance.

Time for a road test: fuel tap off–on–res; there’s no flood button on the Pallas carb, but a little choke lever on the left-hand side of the carb, which is confusingly marked as ^AUF (in German = ‘On’ in English) in the up position, except it isn’t, because when the lever is up the choke is off! Yes, when the lever is down the choke shutter is definitely closed so the choke is ‘on’. AUS is German for ‘off’ so we’re not imagining this? You absolutely need the lever up to open the shutter for normal running, and we don’t know if this is a Pallas thing, or a German thing? Confused? We are...

The clutch lever has a nice enough action, and we turn the twist-change forward for first, selection seems fine, the clutch bites as the lever releases, throttle on, and the motor torque makes the take-off easy. Throttle down, change back for second, and the motor still capably pulls through the ratio increase. Our support vehicle sat-nav paced steady comfortable cruising up to 30mph on the flat, and tracked the light downhill run at 33–34 max. The onboard VDO speedo proved one of the most defective instruments we’ve seen, sometimes randomly indicating up to 35mph, though generally tending to show slower while the revs increased toward the paced maximum speed, and only indicating 20mph! The faster you went, the slower it indicated! It simply didn’t seem to equate to whatever speed you might be actually be doing, and was among the most useless speedometers we’ve ever experienced.

The lights worked fine, beam–dip, and the horn croaked excitedly, all controlled from the curious Hella Bakelite switch. There’s a two-position rotary switch on top for lights off–on, then another smaller two-position rotary switch on the side for beam–dip. Another push button at the bottom facing of the switch unit works the horn, and another push button at the bottom front is the engine cut-out. It’s an interesting and unusual switch.

Handling was fine on smooth tarmac, but hitting bumps and potholes delivered jolts through the rigid rear, and the saddle springing didn’t really help much. The springing on the front forks works OK, but there are no seals in the leg caps, so there’s a constant loss of essential grease—you pump it in the top grease nipples, it runs out the bottom and you wipe it off, then pump some more in the top. That’s how it works!

Brakes were pretty good, the rear could lock up easily without restraint on back-pedal pressure, and the front controllably effective on the hand lever.

It feels light to handle, so lets put it on the scales: 3st front, 3st 5lb rear, so pretty well balanced at a total of 89lb, and a couple of pounds lighter than the period Mk 1 Norman Nippy at 91lb. The Norman models only put on weight as they progressed through their series up to the Mk 4 at 119lb, but the Gadabout models mostly remained much the same.

The P39 Gadabout with two-speed Rex engine was de-listed in July 1959, to be succeeded by the P45 Gadabout with two-speed Villiers engine from July 1959. The Villiers version was £5-5s cheaper.

Other Gadabout models followed the original P39. There was a version with swing-arm rear suspension made for special export to New Zealand. The P45 with a Villiers 3K, a P50 with a three-speed Rex and further swing-arm rear suspension special NZ export versions of both these models, then the final Motobécane based Mk4 Gadabout PM2.

The British Cycle Corporation was formed in 1956 as a subsidiary of Tube Investments, consisting of Phillips Cycles, Hercules Cycles, Armstrong, Norman Cycles and Sun Cycles.

TI finally acquired British Aluminium after a protracted struggle lasting through the years of 1958 and 1959. Raleigh Industries were acquired in 1960, bringing further Raleigh-owned brands BSA Cycles, Humber, Triumph, Rudge, New Hudson, Sunbeam, Three Spires, Sturmey–Archer, and J B Brookes under the British Cycle Corporation; then Tube Investments appointed Raleigh to rationalise the BCC.

Raleigh subsequently ‘cancelled’ Phillips and continued the brand in Nottingham using their own frames.