Back before the world of Mercury was lost…

It wasn't until after the war that the Mercury Cycle Company was formally registered and established at Stratford Road, Birmingham in September 1946, on an authorised capital of £3,000. Mercury seemed to be one of those new businesses surfing the post-war wave to meteoric success, for within just two years they had secured significant North American export orders for bicycles; expanded into another factory at Dock Lane, Dudley; and were employing some 200 people.

Mercury military bicycle

Various Mercury cycles were also produced for military contracts that were traditionally secured on the basis of very competitive tender bid pricing to a defined specification.

Pillion bicycle for Cyclemaster

The first motorised products, launched in the early 1950s, were heavy duty cycle frames constructed for installation of the Cyclemaster motor wheel, and sold in gent’s ‘diamond’, and lady’s style ‘open’ frames. 1953 listings added the option of a pillion frame with seat pad and footrests, and the Roundsman: a one hundredweight rated delivery frame with a small front wheel and a large carrier.

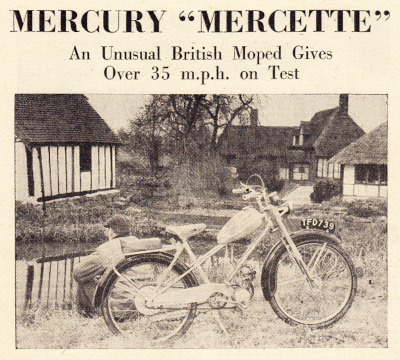

All four Cyclemaster-based motorised products continued up to 1955, when aspirations moved up another gear as Motor Cycling’s edition of 10 November announced that Mercury was entering the lightweight motor cycle market with the four-stroke Mercette moped and Hermes scooter with 49cc Ilo engine. The remarkable Mercury Mercette was a surprise appearance at the Earls Court Motor Cycle show in 1955, particularly because it would subsequently transpire to be the only British four-stroke moped ever made!

After the Earls Court Show in 1955, the Mercette was recorded in manufacturers' lists from February 1956, but didn't actually start arriving in showrooms till July, so most of the first sales season had been missed. This delay must be credited to engine supply. The motor’s only identification was the mark of ‘Mercury Industries’ moulded into the dipstick cap, but its true origin would not become apparent to the motor cycling public until April 1957 when the Hounslow perambulator manufacturer Dunkley announced its Whippet ‘60’ light motor cycle. Dunkley built several kick-start variations on its little four-stroke engine theme, but the pedal-start Mercette motor was uniquely made for Mercury, and few parts were compatible between the types.

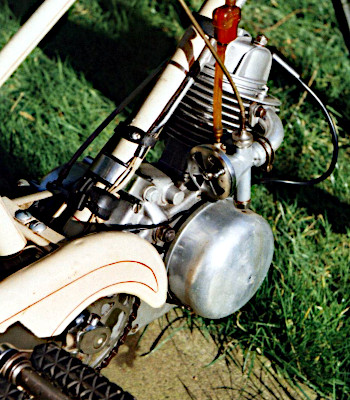

The 2bhp @ 5,200rpm ohv Mercury engine was obviously an original design and a marked diversion from the two-strokes that dominated the smaller capacities. Of all alloy unit construction with two-gears and a dry clutch, the 39mm square bore and stroke calculates out at 46.6cc, but Mercury chose to call it a ‘48’. The round fins on the alloy barrel and cross-flow head gave it a quaint and distinctive appearance, with a ½" Amal 360 carb on the right and sweeping curvy exhaust pipe to the left. A Wipac Series-90 was the chosen electrical set mounted directly on the crankshaft, so it produced a wasted spark on alternate revolutions and featured no ignition advance–retard facility, though the motor seemed to start and run all right! Lubrication was described as 'splash/oil mist', meaning there was no pump, and basically it relied upon the crank flywheels and gears just chucking it all about. The motor’s internal mechanics were where the real mind-bending stuff went on, with the cam lobes being integral on the gear input shaft between first and second! This was driven from the crank pinion by a reduction idler gear, which all required lining up when cam timing; no problem there, but when you rotate the crank and the marks only line up again after eight revolutions, you do wonder if you're going a bit mad! It may all sound very technical, but it actually reduced the number of components involved and made the engine quite straightforward to assemble, just as long as you didn't try to think too hard about how that cam timing actually worked.

Mercette ‘48’ engine

The Mercette rigid frame pattern is known as a mixte (from the French for mixture, being suitable for both men and women), which construction was renowned in the cycle world for its strength, and became the favoured form for the old style Cyclo-Cross events. A negative aspect of the design is that it tends to make the upper frame space physically wider than a normal bicycle, and can become a problem when pedalling, though obviously not much of a concern with a moped. Front forks were sprung telescopic, simply greased and undamped, and the 26"×2"×1¾" wheels were amply covered by heavy, side shielded mudguards. The reason the rear carrier was so substantially constructed was its dual function as a sub-frame for mounting an optional pillion seat with rear footrests, so Mercury was obviously very optimistic about its machine's capability.

Other options included a Smiths speedometer kit mounting on the front wheel, and even a factory megaphone to replace the standard Burgess sausage silencer. Illumination, in no great excesses, came from 6V Miller cycle lamps around 6W/5W front and rear, while the token Miller horn was far less likely to frighten the chickens than the racket coming out the end of the exhaust pipe. Finish was a Mercury light grey (which generally seems to fade to beige over time), with maroon mudguards, then lashings of pinstripe coach-lining all over everything, which was part of the cheap and popular fashion to brighten-up the post-war years of austerity. Still, the Mercette was a large and skinny clothes-horse so it wore these trappings fairly well, unlike some of its smaller wheeled contemporaries, which looked like tacky, over-decorated seaside souvenirs (Yes, Hercules Her-Cu-Motor, we’re looking at you).

So much for the general overview, but confronting the Mercette face-to-face is a whole different thing—this really is one big-framed moped with a 47½" wheelbase and 76" total length. The saddle stands tall at 35", though the bike is by no means heavy at 7st 3lb (46kg), since its structure is just a very skeletal cycle frame with the little engine dangling beneath the front down-tube.

The wise move with a mythical creature like this, is to study and understand the complications of the bizarre contraption you are obviously proposing to ride before naively taking off and killing yourself, and this is just the machine to do it! It’s a two-speed hand twist-shift with a normal lever clutch, so you'd naturally expect to find a back-pedal brake … but it's just a conventional cycle freewheel, so follow the rear brake cable back to its source and you end up at the right hand lever! So where's the front brake? There's a second lever on the left bar cluster with the clutch and gear-shift, and now you know you really are in trouble! Since humans haven’t yet evolved with two hands on their left arm, for a mere mortal to ride one of these devices with any chance of surviving is going to take a very different technique. The plan is, whenever you want to slow down, to switch into neutral first so you can control both brakes as much as required, though this will introduce some operational delay to the application of the front brake, so riding with anticipation becomes an essential element. Not a fast riding style, but we may at least survive.

The two Mercettes from our 2002 article.

Fuel on, and starting was generally found to be more effective by lifting the flood chamber button and checking that the off–on–light switch is in the central position (since left position is engine cut-out). If you turn the pedals out of gear then it’s just like pedalling a bicycle, and only the back wheel goes round. On the stand, either push down on the pedals in second gear, or pedal away then clutch into either gear. With a little throttle the motor starts quite readily, then switch into neutral and keep it going on the throttle. If you chose to use the strangler instead of the flood, then you end up having to stop and stretch over the frame to open the strangler.

It’s best practice with splash oilers to give them a minute at low revs to get the oil round ... then taking our life into our hands, it’s off we go! First gear goes in with a light clunk, but no snatch, which you should expect since the clutch is mounted off the outside end of the output shaft between the front sprocket and the gearbox, not between the engine and gearbox like conventional engineering practice. So, remembering that every shift is technically going to be a crash change, it’s a relief to find at least the dry clutch feeds in nicely, and turning on the throttle the Mercette surges up the road with a throaty growl. Crash into second with a big ratio jump and build up to a steady chuffing cruising speed, then hope you're not going to have to stop again too soon. Settling down on the move gives you a chance to take stock of your precarious situation. Because of the tall frame you have a high centre of gravity, and with the long wheelbase, the ride becomes more stable with speed. The amount of clattering, whirring and general engine noise that comes up at the rider could easily be enough to cultivate total paranoia in the mechanically sympathetic, but all accompanying riders say it sounds just brilliant so maybe it’s best to go with their opinion. The oddest thing is thundering along at 25mph on this thing sounds like a 250 BSA, which is certainly some cause for confusion and amusement to spectating pedestrians, who look round for a big classic bike, and see: a peculiar engined moped! The undamped telescopic forks soak up the worst of the road bumps, but the rigid rear end proves quite a test of durability for the rider. Once you get used to the whole alien experience, the handling manners feel quite good on smooth roads and it’d take a brave (or crazy) rider to push it to cornering limits. Despite the 2bhp rating of the motor, it’s only got half the firepower of its two-stroke cousins so tends to fade away on inclines in top gear. The lights don’t prove to be too bad considering their feeble wattage and are not far below the limited capability of the performance. Riding the Mercette is real biplane aviator stuff, and it surely ranks among the most fantastic rally machines for sheer rarity, general interest and that wonderful four-stroke sound. Twist on the throttle and it bops away like a classic single, then running at cruising speeds of 25–30mph and the motor’s snarling at the world as if it really means business, then roll down the throttle and there’s that familiar overrun growl. The Mercette is a moped that thinks it’s a big motor cycle! When chuffing along a smooth, clear road it’s a marvellous ride, but in practical terms: Kamikaze pilots only!

Mercury quoted a top speed of 37mph solo and 30mph two-up, there may seem to be some optimism here, but such claims are unlikely to be tested much on such an elderly and rare machine. Our Mercette was never fitted with a speedometer, and we never did any top speed pace on it for the original article, so never really knew what it was actually capable of.

In the Cycling road test of 12 December 1957, the Mercette was fitted with a speedometer (maybe a Smith’s magnetic), and reported ‘flash’ readings up to 45mph on down gradients.

Dunkley and Mercury seemed to share many common parts on their machines: petrol tanks, front forks, and even paint. It was sometimes hard to tell where one company ended and the other began. Mercette frame serials ran from 100 to 765 by October 1957, at which time Mercury was getting into financial difficulties. By the next month, the reduced workforce was on short time, and what resources the factory had in the ‘motorised division’ were probably being concentrated on the new Pippin Scooter. The Palace of Cards collapsed on March 1st 1958 and all production at Mercury ceased on this date. With massive debts, Mercury Industries entered into voluntary liquidation on the 20th March. The brief flight of the winged messenger of Roman Gods was over. The buying public never did take to the Mercette, and who could blame them? It was a user-unfriendly monstrosity that developed an unpleasant mechanical reputation for dropping its valve seats out of the cylinder head! There is little evidence to suggest any more Mercettes were completed beyond the 665 October figure, and the few rare and invaluable survivors leave just a tiny window to glimpse back into the Lost World of Mercury. Dunkley continued briefly, introducing its 49cccc Popular Major Scooter in December, but by spring of the next year had been taken over by M.G.Holdings, who also swallowed up Dayton Cycles, and in May transferred all production to the Park Royal site. This was probably no more than an asset stripping exercise and simply building out acquisition stock, since the Dunkley range was dropped at the end of 1959, followed by Dayton models also going out of production after the 1960 season.

Our original ‘Lost World’ article on the Mercette was produced for another publication in April 2002, before we started IceniCAM and before we started performing paced road tests, since which time the Mercury had been extensively rallied at UK events, as well as in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. The motor dramatically and very terminally expired on the 11 April 2010 Radar Run event, and it subsequently proved that the internal damage was so extensive as to be irreparable, while suitable replacement parts were simply not available to repair the original engine.

The Mercette was down, but this was not the end, because there was a crazy plan to evolve something that Mercury never made: a Super Mercette!

Options of trying to fit any of the Dunkley engine models to the Mercette frame would be obviated by the fact that all the Dunkley motors have a substantial kick-start boss that would completely foul the Mercette pedal sprocket, so you can’t fit any Dunkley engine, and if you convert the frame to footrests, then it’s no longer a moped.

You can’t fit the Dunkley internals into Mercette crankcases because the journals and main bearings are different sizes, and the larger 44mm cylinders won’t fit the 39mm crankcases … snookered … except … taking a Dunkley Whippet 61cc motor, removing the complete kick-start mechanism, cutting the boss off the case, and alloy welding a blanking plate in place to reseal the case, then carefully retexturing the surface with an engraving tool so it matches a sand-cast finish … you’d never know …

A total engine rebuild, and we have a 61cc, 2.4bhp Mercette compatible motor, offering 33% more cc and 20% more bhp. It seems likely that this would cope with up-gearing … so the time for some comparative maths …

The Whippet ‘60’ has a 10-tooth front sprocket and a 44-tooth rear sprocket on 2.00–19 (23") road wheels giving a 72" circumference. 44 ÷ 10 = 4.4 and 72 ÷ 4.4 = 16.36; therefore one rotation of the front sprocket moves the Whippet forward 16.36".

The Mercette has a 10-tooth front sprocket and a 54-tooth rear sprocket on 26 × 2 road wheels giving a 81.7" circumference. 54 ÷ 10 = 5.4 and 81.7 ÷ 5.4 = 15.13; therefore one rotation of the front sprocket moves the Mercette forward 15.13".

The Whippet is higher geared, which is no surprise since the Mercette is lower powered.

The Dunkley Popular scooter has a 10-tooth front sprocket and a 48-tooth rear sprocket on 2.50–15 (20") road wheels giving a 62.8" circumference. 48 ÷ 10 = 4.8 and 62.8 ÷ 4.8 = 13.08 (13.5% lower geared than Mercette).

All of which is probably of little concern to any standard machine owners, but when you get into specials and are looking at putting a Whippet 60 motor into a Mercette—it’s going to be a bit revvy isn’t it? 7.5% under-geared in fact! This means that the Mercette ‘60’ would be dropping 2.25mph @ 30mph based on the same revs. To correct this error requires adjustment somewhere. Changing the Mercette rear sprocket is out since it’s an integral part of the hub and the spokes are laced through it! Alterations inside the engine are very difficult, so that really narrows it down to changing the front sprocket, which is an integral part of the clutch cage centre boss (it may not be easy but it’s the least difficult option). Raising this to an 11-tooth front (Mobylette donor) to the 54-tooth rear = 4.9 and 81.7 ÷ 4.9 = 16.67. That’s a gearing increase of 1.9% over the standard Whippet ‘60’, so would add 0.6mph @ 30mph based on the same revs—ideal!

So cut the 10-tooth front sprocket off the back of the clutch basket, and copper-bronze weld a new 11-tooth sprocket in its place. This suggests that 40+mph might now be possible on a Mercette, but would you want to be doing 40+mph on a bicycle with poor brakes?

Hold that idea for a moment, because when we got the Super Mercette going for the first time, there were obvious problems with clutch slip. We’d fitted the Whippet dry clutch, which uses two stronger heavy-duty springs (instead of the five smaller springs of the Mercette), and employs a single plate with two friction plates riveted or bonded to the centre plate, so there are two effective friction faces taking the transmission load. The problem was addressed by making a new steel centre plate, and two floating friction discs, so now we are effectively spreading the transmission load across four friction faces—and that solves the slipping issue!

Another aspect of the engine conversion is that it now proves practically impossible to ‘kick-start’ the bike on the stand because of the increased capacity and compression ratio. The only practical starting process is now to pedal off the bike to build up pace, then switch into gear (second or first) to ‘shock’ the motor into turning over and starting.

The Whippet 362 carburettor is the same ½" size as the Mercette 360 carb, and both run a 35 main jet, but the 362 doesn’t have the ‘flood’ option which Mercette starting practically relied on, but so far the Whippet engine’s starting doesn’t seem to even need use of the strangler!

The exhaust note has noticeably changed, and has a sharper ‘crack’ to its tone now, more Sports Tiger Cub than a soft and woolly C15.

With the clutch sorted, the 10% increase in drive ratio is immediately noticeable, though it proves no problem for the motor to pull as pace still capably increases in second gear. Our Mercette is clearly going to be faster now, but increasing the brake cable wire diameters from 1.5mm to 2mm just seems to deliver a limited improvement as you can now only pull on the same awful brakes a little harder. It’s still necessary to anticipate and plan ahead for safer riding, so you try to maintain a ‘reaction gap’ to any vehicle in front…

With the increased drive ratio, low speeds in second become a little more prone to snatching, so comfortable cruising speeds are now found between 22–35mph. Top speed on the flat paced at 40mph in still air, and on a light downhill 41–42mph, which would also probably be expected with a tailwind on flat.

We couldn’t find any archive reports on the top speed of the Whippet ‘60’, but Dunkley did claim 45mph for the Whippet ‘65’ Sports, which was 64cc with a higher compression ratio, and rated at 2.6bhp, so our pace of the Super Mercette appears to be within expectations (it still doesn’t have a speedo).

The rigid rear frame still delivers a hard ride on rough road surfaces, the engine still fades against inclines, and produces a lot of mechanical clatter from the backlash of all its internal straight cut gears. The Super Mercette is still just as fragile and prone to failure for any other of the multitude of Dunkley related reasons, and far from being a perfect bike—but when it works, it’s a fantastic machine to ride …