Before joining Raynal in presenting a Villiers Junior engined autocycle for sale in 1937, Excelsior had previously started with 98cc Villiers engined motor cycles as far back as April 1931 in the form of a Universal AO model with two-speed gears operated by foot-change rocking pedal. It had a simple tubular frame with blade girder forks and was the lowest priced machine on the market, listed at a mere 14 guineas, though it came as standard with no lights.

A carbide lighting kit was offered as the cheapest illumination accessory for 15 shillings, or a further direct electric lighting set for 25 shillings.

98cc Universal models were annually updated by model prefix, BO for 1932, CO for 1933, DO for 1934, and EO for 1935, then seemingly replaced in the range by a 125cc version, until briefly returning in 1939 as a 98cc JO model with a longer frame, larger fuel tank, and also listed with a 125cc JO model, which continued as 125cc KO in 1940.

The popularity of autocycles effectively replaced Villiers engined light motor cycles for about a decade, until the first 99cc F-series motors were announced in late 1948. The 1F was a new two-speed trigger-change kick-start light motor cycle engine, while the 2F was a single-speed replacement for the Junior De Luxe.

While other manufacturers readily adopted the new Villiers engine models to produce new autocycles and light motor cycle frames to fit the new engines, Excelsior chose to continue with their wartime investment in their own S1, SII, and G2 autocycle engines and frames. The problem with this decision was that the Excelsior models quickly became outdated designs in comparison to their competition, which must have begun to compromise sales.

Further to this situation, Villiers replaced the two-speed 1F engine in October 1952, with a redesign. They introduced a new 4F two-speed trigger-change kick-start engine, which all other manufacturers began switching to, and the Excelsior G2 and Spryt autocycles began looking even more obsolete.

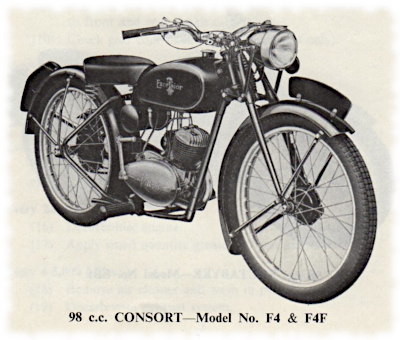

During 1953 Excelsior finally presented a new Consort light motor cycle to take the Villiers 4F engine, with a rigid frame, tubular girder forks, single saddle, and direct lighting set, which was somewhat inexplicably named model F4.

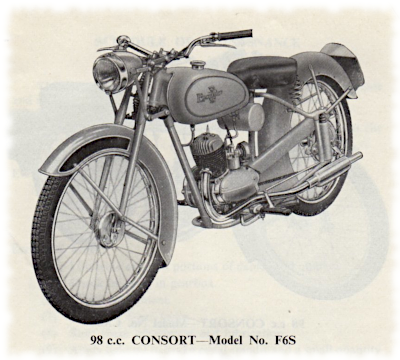

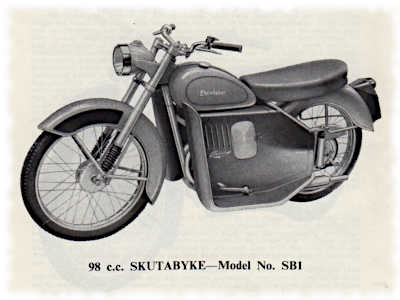

In 1956 the rigid F4 Consort was joined by a plunger sprung frame F4S version, which from April 1956 was fitted with a new Villiers 6F two-speed foot-change engine, so creating another new Excelsior Consort F6S model. When the new range for 1957 was announced, a new 99cc Skutabyk SB1 model appeared; this evolved from the F6S Consort fitted with battleship armour-plated panelling formed complete with one-piece leg shields, and was every bit as attractive and stylish as it sounds.

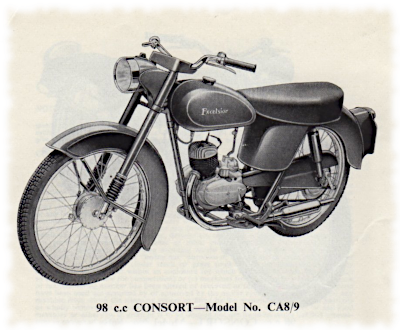

The F4 and F6S models also continued through 1957, then both Consorts were de-listed for 1958, though only to be superseded by a new Consort CA8 model with a 6F engine in a new frame with swing arm twin shock rear suspension, telescopic forks, and a dual seat (maybe functional, but a visually crude machine).

The new Consort continued into 1959 as CA9, but was joined in April by the return of the former F4 rigid Consort, with tubular telescopic fork set and called F4F.

Since our featured bike was originally registered 138 CRT by East Suffolk CC in July 1959 we’re very confident that this is a Consort F4F model, and it complies perfectly with the specification.

Finally the Villiers motor has evolved from the dreadful trigger change 4F to the more sensible foot-change 6F; so now we get to try one and this 6F Excelsior Consort F4F looks like a proper little single-seat motor cycle.

Our bike has a small single position lever tap under the left-hand side of the petrol tank, which is OK, because there’s a balance pipe across the two halves that allows fuel across to the tap side without having to lean the bike over when the level goes down. The bad news is that you have to drain all the fuel if you want to remove the balance pipe to take the tank off.

Starting is a little different from earlier 1F, 2F, & 4F models with the Villiers Junior carb, because now the 6F engine is fitted with the newer Villiers S12 carb. We’ve found these a little quirky on starting on other models in the past, so there’s a bit of guesswork in our first attempt. It’s a cold day, so choke on (raise to engage), maybe a little tickle, then a couple of kicks and it fires right up. That seemed surprisingly easy, but within a few seconds the motor starts choking up, so quickly push off the choke and hold the revs on the throttle a moment to clear. That was certainly better starting than others we’ve tried, and the motor is ready to respond to the throttle very quickly too, so we don’t even have to wait for it to warm up!

Clutch in, up for first, which engages with a clunk, but the bike doesn’t creep forward, so the clutch is OK. Power on and feed in the clutch, and the take-off seems fairly brisk for a nearly sixty year-old Villiers of 99cc. Because the motor is only two-speed, there’s no pressing need to hurry up to the next gear, while the torque and flexibility of the Villiers engine makes the process easy and pretty much stall-proof.

When you come to switch up for second is about the point that you first find yourself looking down for the gear lever. The reason for this is it’s not conveniently located where you might expect it to be for your toe. In fact it’s way forward and above of your toe. The selector on the 6F engine doesn’t return the gear lever to the centre position, so it stops in the up position where you left it when you engaged first, and yes, it’s meant to work like that, because the motor was converted to foot-change from the 4F trigger-change, and that’s how it works.

The toe lever is also so far forward that you might think it’s the wrong gear lever, but that’s also correct, so you end up having to lift your foot off the footrest, then clomp your boot down on the lever. The change however switches quite lightly, so its easy to overdo the pressure you put on the gearshift, which isn’t so good because a thin hardened steel selector rod in the gearbox with two 90º bends is commonly prone to snap its ends off and disable the gearbox, so heavy changes are not a good idea.

These foot-change selector rods are frequently found broken on the 6F motors, so it’s something you need to keep in mind, and it’s a big motor strip down to replace the rod too.

Shifting down to second, the gear lever travels twice the distance you’d expect, because the selector hasn’t self-centred, so you’re shifting from first position, through neutral, and into second, this is effectively the full distance of a two-speed box, from bottom to top. With the long gear lever, it also gives a higher leverage to help that selector rod to snap, so it’s really not a good formula.

Now in second gear, the gear lever continues to sit in the low position, so you next have to place your foot well down and forward to get under the toe lever, which is another somewhat awkward action where you might find yourself lifting your foot off the rest again.

Basically that gear lever is always going to be in the position you left it, and the only time it’s in middle position is when the box is in neutral.

Is the foot-change actually an improvement on the trigger hand-change, or is it just as bad in a different way?

The overall performance of this Consort is quite impressive for its age and capacity, and Villiers issued motor specifications of 47mm bore × 57mm stroke, with 8:1 compression ratio, for 2.8bhp @ 4,000rpm. The bike powers up to town traffic pace very capably, then easily continues up to between 39 & 41 mph along the flat according to wind conditions or adopting a crouch, though you don’t have to crouch much because the seating position is very low anyway. Taller riders are probably going to find the riding position too low and cramped, and there’s not really any obvious means to adjust that, so the Consort may not be a bike to suit every size.

Handling was confident, and it handled quite well for a lightweight rigid machine, feeling well planted on the road—until you came across a bumpy surface at speed around a bend. The rigid rear might step out a little, but the most annoying thing was that the stand spring didn’t seem strong enough to hold the stand up and, over bumps, it swung down to bang on the road.

This was both annoying and disconcerting, because there’s always a worry that the stand might catch and make the moment more exciting than was planned!

The 6F motor evenly drones along at 40, then its revs climb further as we run into the downhill phase, the exhaust note pitches higher, indicating we’re going faster (no speedo). The engine continues with clear two-stroke firing right up the range, so seemingly with nothing to hold it back, and a clear and smooth tarmac road surface with no bumps to upset the handling, we go for max and tuck down for our pacer to clock us off at peak reading of 48mph. That was pretty impressive, and nearest the best result we’ve ever had from any F-series (except the Stella with its 9F 4.7bhp Kart engine).

Nor did our Consort even object, it handled the revs quite capably, with little in the way of vibration, and even running with no hint of four-stroking even though it was going though its quickest point with the motor off-load.

Straight into the hill, and the engine expectedly dropped revs up the climb, but still topped the rise at 30 in top, and showed no suggestion that it ever might have wanted to change down.

Along the flat you can feel that the motor gets blown down against a blustery day, but the characteristics of Villiers engines seem to slog through these conditions regardless; they may slow a little, but they never give in.

Returning to base, we find the motor ticks over with a slow pounding beat, but there seems no way to actually stop it, no switch, no cut-out button, so we end up turning off the fuel tap and putting our hand over the air filter till the engine finally peters out.

Parking up is when you get to the next big gripe about these Consorts: the stand again. It’s a horrible thing to operate! The bike is nice and secure on the stand, but how hard can it be to put a bike on and off the stand? After all, it’s only a small bike! You wouldn’t believe how unpleasant this is until you’ve actually experienced one of these machines, because you have to physically lift the back of the bike up by 5 inches (no wonder the rear carriers frequently break); then, rolling the bike on the stand through its effective arc, the machine travels an unbelievable 15 inches! This means that if you’re parking the bike back up to say a garage wall, you have to leave at least a little more than a 15-inch space to start pulling it back onto the stand, or you’ll end up smashing the rear light.

Considering all the years that Excelsior had been making motor cycles, you’d think they could have produced something better than that!

The telescopic forks worked the road well, giving a good ride at the front.

The 6V × approximately 27W direct lighting set produced a reasonable headlamp, certainly an improvement on the preceding generations of autocycles. Unfortunately someone had chosen to add a stop light onto the rear brake, which gave a nice bright warning—until you switched on the lighting set. Since the lights are rated to operate at the constant generator output, with no regulator or battery involved, they work until you touch the rear brake, where the stop light robs all the generator power and you’re plunged into darkness!

How dangerous is that?

Single-circuit direct lighting sets should never be retrospectively fitted with a brake light. MoT testers should know this, but many don’t appear to, and some people think that every motor cycle and moped should be fitted with a brake light. Absolutely not! If it wasn’t constructed with a brake light, then there could be a very good reason for that, so you shouldn’t fit one.

The horn is just a simple bulb hooter, and yes, that is legal, since using an AC electric horn around 17W could have exactly the same effect on the lights as adding a brake light.

The Consort exhaust pipe is a fascinating piece of plumbing, writhing like a snake under the engine, then curling out from underneath with a 4-inch set to the left to exit behind the footrest and connect into the silencer. The exhaust note it produces is most pleasant: a deep and mellow pulsing beat at low revs, and its tone throughout the rev range sounding a suggestion of greater power beyond the engine’s actual capacity.

The 4-inch front and 5-inch rear brakes were both effective and capable within the very good performance of this machine and, excepting bumpy corners at speed (due to the rigid rear frame), felt confidently planted on the road for most of the time. The F4F Consort 6F generally proved a good riding machine, went well, and followed a chosen line when hustled through bends.

The F4F was reclassified as F10 for 1960, while the miserably selling Skutabyk finally sold out the last of its old stock and was discontinued, though last years CA9 Consort still continued into the New Year as CA10.

1961 continued the Consorts as CA11 and F11, from when subsequent ‘changes’ mainly related more to annual model references rather than much effective development. These were tough times in the British motor cycle industry and great names of the past were now dropping like flies.

Along with discontinuance of the twin-cylinder models, the ‘old faithful’ rigid Consort F13 frittered out in 1963, while production of the C14 Consort ended in October 1964, not that Excelsior had particularly wanted to end the model, but primarily because the supply of 6F engines had become exhausted since Villiers had discontinued the motor in the early 1960s.

Excelsior manufactured its last motor cycles in 1964, and the business folded in 1965 with its trading name and assets purchased by Britax.