1817 … In the beginning, and credited to the invention of Baron Karl Von Drais, there was the Drasine, a primitive and heavy contraption made out of wood. Resembling the general shape of a bicycle, this German Laufmaschine (running machine) came to be widely popularised, being more commonly known as a Velocipede in France, and Hobby-Horse or Dandy Horse in Britain.

In 1859 James Starley mended a broken sewing machine, and was taken on at the London factory of chair manufacturers and sewing machine dealers Newton, Wilson and Co of Holborn, London. While in their employ he proposed some successful developments to double chain-stitch machines, which led him to further technical improvements and mastery of the mechanisms.

A partner in this business was Josiah Turner, who took a great interest in Starley’s developing skills and often visited him socially. By working at home in the evenings to develop his ideas, by early 1861 Starley had produced his own model of sewing machine, designed to stitch round the edges of cuffs or the bottoms of trouser legs after they were made up. This machine was made at home in the evenings.

On 14th May 1861 James Starley left Newton, Wilson & Co, then, with Turner and Silas Covell Salisbury, an American, went to Coventry to embark upon the importation and marketing of sewing machines from America. Renting part of the premises of a Mr John Newark, Salisbury and Starley patented the design of Starley’s ‘European’ sewing machine, but establishing their own business to return a profit proved somewhat more difficult.

In September 1861, local social interest in finding work for under-employed watchmakers led to the formation of the Coventry Sewing Machine Co, which secured the designs and services of Messrs Starley and Turner. The pilot works established at Little Park Street, Cheylsesmore, Coventry, and an alternative title of the European Sewing Machine Company was adopted for sales into France. Expanded premises were soon needed and the business occupied a larger factory at King Street, Cheylesmore, Coventry where European, Express, Godiva, and Swiftsure model sewing machines were produced.

In 1865, M Michaux at 29 avenue Montaigne, Paris pioneered the earliest form of pedal rotary crank on a velocipede, and began to offer these commercially for 200 francs. The Michaux bicycle was shown at the Paris Exhibition of 1867; examples were purchased by Rowley B Turner, who brought them back to England and convinced the Coventry Sewing Machine Co to begin making small numbers of these velocipedes for the British market, making this the first British company to manufacture pedal cycles.

In 1868 the Paris agent secured an order to build some 500 ‘Michaux’ bicycles for export to France, and the company reformed itself as the Coventry Machinist Co to handle the order.

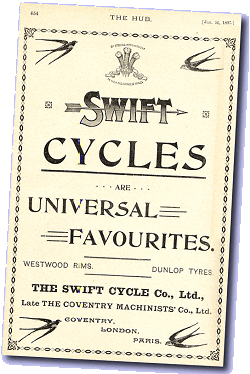

Unfortunately however, the Franco-Prussian War intervened, and the French agent welched on the deal, leaving the company unpaid for their works and out of pocket … but not for long, as the business speedily registered the name of Swift Cycles, to sell the bicycles for themselves.

Many key individuals were to begin their cycle careers at this business including James Starley, William Hillman, George Singer, and many others, before starting up their own further cycle businesses in Coventry.

The European Sewing Machine Company was liquidated in 1869 as there seemed more interest and business prospects in the new bicycle trade than the established and saturated sewing machine market.

In effectively becoming the pioneer of British cycling, the Coventry Machinist Co also provided the cradle for this developing industry, from which a number of key names would soon emerge.

At this time James Starley was foreman of the company and instrumental in development of the basic velocipede, however, in 1870 he left to set up in business with William Hillman, and produce the Ariel bicycle, a significant landmark as the first all-metal lightweight cycle.

1882 Bayliss Thomas tricycle

Over time, the physical form of cycles began to develop, with improvements to the ‘Ordinary’ or ‘Penny Farthing’, up to Swift ‘Safety’ machines in the late 1880s. Starley’s position as foreman was filled by Thomas Bayliss, who with other workers John Thomas and John Slaughter, subsequently left to establish their own business in 1874. The new firm was registered as Bayliss, Thomas & Slaughter Co, producing from premises at 287–295 Stoney Stanton Road, Hillfields, Coventry, and was one of the earliest manufacturers of ‘Penny-Farthing’ type bicycles under the Eureka and Excelsior brands.

The company shortly changed its name to Bayliss, Thomas & Co, although Slaughter remained a director of the business.

During an exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1896, Bayliss, Thomas & Co presented and demonstrated a motorised cycle fitted with a 1¼hp Minerva engine. Around 250 people tried it without mishap, so the company went on to develop a further commercial model powered by a 2¾hp MMC engine (Motor Manufacturing Co of Coventry), which was commercially sold in 1896 under the Excelsior brand—to become the first British motor cycle.

In 1897, the Swift Cycle Company was formally launched to take over business of the Coventry Machinist Co—the following year they began making motor cycles as well as cycles.

By 1902 Swift had developed single-cylinder motorcars and by 1905 a four-cylinder model, followed by others. In 1915 Swift ceased the manufacture of motor cycles to concentrate on car production, which lasted until 1931—another casualty of The Great Recession. The name was bought by Kirk & Merifield, and production moved to their Birmingham factory.

Hot on the heels of Raynal, Excelsior joined the autocycle market with a ‘surprise announcement’ Autobyk at the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1937, making them the second manufacturer offering machines equipped with the new Villiers Junior engine. Many more would follow.

The Junior De Luxe motor soon replaced the earlier Junior type but, during the war, Excelsior established its own engine manufacturing shops, intended to produce further motors for the Military Welbike, though these weren’t completed before the war ended, but were ready and available to provide engines for civilian production in 1946.

The ‘first’ production Excelsior ‘autocycle’ engine was technically the (first) Spryt motor type described in Motor Cycling magazine in March 1946, for application in the civilian Corgi design derived from the military Welbike. It would however be 1948 before Brockhouse Engineering delivered Corgis for sale.

Excelsior returned to civilian sales in 1946 with its pre-war Autobyk and Villiers Junior De Luxe engine. At announcement of Excelsior’s new ‘Super-Autobyk’ with own-built 2-speed ‘Goblin’ engine in August 1946, the Villiers JDL model Autobyk became coded V1 (maybe unsubtly intended to put customers off their competitors ‘Doodle-Bug’ engine?).

‘It’s a Secret!’

Excelsior drops a hint about its

new Autobyk in 1937

The V1 motor option was listed up to the JDL engine’s obsolescence in 1949.

The G2 Autobyk was available for sale from May 1947, and by the end of May 1947, another autocycle engine model had joined the Excelsior line-up!

The S1 Spryt B (indicated as MkII cast onto the crankcase) was basically a cheaper single-speed version of the Goblin motor, but the geared G2 offered an appreciably higher overall top ratio, raised to 8.5, from just 11.3 on the single-speed Spryt, representing a mathematical 25% increase, and better performance potential.

For our first test of the day we proudly present an Excelsior G2, the only British-built two-speed autocycle.

Petrol tap is found at bottom left of the 11 pint fuel tank. There’s a small operating lever attached to the choke shutter on the Amal 259/001 carb, and a flood button to the float chamber, so there shouldn’t be any problem getting it rich enough to start, however cold the weather.

With neutral located between bottom and top, push down/forward for first, and all the way back/up for second. It’s hard to tell quite how well the gearbox selects its ratios, since with Archimedes advantage of an 8½-inch gear lever, you’re probably always going to be able to force the change, though we’re advised that selection can be made easier by double-declutching. Gently turning the rear wheel and moving the lever, the drive ratios both locate plainly enough, and neutral is easily found with a positive click in the middle, but such things don’t necessarily work quite the same under load.

Since G2 has a neutral, this is a rare autocycle that doesn’t have a latching lever on the clutch. It’s generally preferable to engage second gear for starting, pull in the decompression lever at the left hand bar to get the engine spinning, release, and the engine coughs into life with a few thumping blasts of smoke. Open out the choke, and the exhaust tone flattens as the engine clears its lungs.

To avoid embarrassment, it’s always best remembering to switch the gear lever to neutral before pushing the bike off its stand.

Pull in the clutch, and if selection of first from a standstill seems to baulk, then rocking the bike backwards or forwards slightly may help. Tweak up the throttle lever, feed out the clutch, and G2 pulls easily away. As the pace builds toward our next ratio, clutch again, throttle down, reach forward and down for lever ball, pull up and back for top, throttle back, and we’re on our way to find comfortable cruising speeds up to 33mph. Our best on flat with tailwind indicated 37mph by the pace vehicle, since our G2 has no speedometer set fitted.

The Goblin engine on our G2 has received some dramatic porting modifications, with the transfers and exhaust bridge all lifted by 33%, so this motor should theoretically produce more power at revs, and the compression ratio has been raised by one point from 6:1 to 7:1, so we also expect its hill climbing ability to be somewhat improved upon a standard motor.

The Kirton downhill run recorded 42mph, and we charged the hill on the other side to try the climb without changing down. G2 did drop back to 23mph before storming the rise still in top, and giving a far better account of itself than reports might have led us to expect from a standard machine.

Also wanting to test the stories about first being a crawler gear, we wound her right up to pace 26mph in first, so though no one would ordinarily run one of these bikes up to such revs in bottom gear, that rather busts any myth about what it’s capable of in low ratio.

Feeling as if the slightly curving Kirton downhill run hadn’t let us to stretch our G2 to its full capability, we went on for the straighter Brightwell downhill run.

Like some great lumbering medieval monster, our G2 steamed up to a best downhill pace of 48mph! Accounts from the following pace vehicle suggested this performance appeared to be very much approaching the engineering limit, with the back of the bike apparently snaking down the road! It was pretty hard to appreciate this from the pilot’s point of view, being rather fully occupied in simply keeping the brute on track for the record attempt.

Typically of overhung crank designs, there’s quite a degree of rumbling and mechanical noise produced with increasing pace. This really isn’t a region these primitive motors are comfortable in, as slack bearings and old clearance tolerances begin to protest at the revs. They’re much happier pulling under load at lower speed.

With the tweaked porting and raised compression ratio on this machine, we never actually needed any change down to first to tackle any of the hills on our test circuit, but thought we should give the operation a try to see how awkward it might be in the heat of the moment. So, with the revs dropping away against an incline, the rider has two options: pedal assist, or change gear? This decision is likely to be decided by the level of fitness and length of climb, based on the knowledge that G2 will capably manage practically any ascent in low ratio.

Appreciating that trying to change gear at the same time as pedal assisting the machine uphill is highly likely to result in some catastrophic disaster, the decision to go for the change has to be made before forward speed has dropped below the critical point, so it’s necessary to synchronise the following actions. Clutch-in, with left hand also holding the bike on course, while thumbing down the throttle lever on the offside bar, then move your right hand for the centre-frame gear lever to try and crash it quickly down to first (which action requires the rider to lean ahead).

With forward speed rapidly slowing, any temptation to drop the clutch before getting your right hand back to the throttle needs to be resisted; otherwise the resultant engine braking could overcome the rider’s one-handed control at this stage. Only with a second hand back on the bars and opening the throttle, is it actually safe to release the clutch, by which time the bike will have practically stopped! The advice to any other bikes riding with a G2, is don’t be close behind them on hills!

As it happened, any ability to pedal assist this machine on hills became a non-option as the rear hub pedal ratchet quickly ceased to operate during the test, since the bitterly cold day solidified its grease, leaving us with no pedal drive or rear braking functions. Before the mechanism failed, the back-pedal brake seemed to function well enough, and the front brake seemed adequate in joint operation with the rear—but being reduced to the forward brake alone certainly introduced an appreciation of its limitations!

Wheel & tyre size is ‘old’ autocycle 26×2×1¾. Given weight 118lb approx, 11 pint fuel tank.

Square 50mm bore & stroke. Given outputs 1.67bhp @ 2,000rpm, 2.33bhp @ 3.000rpm, 2.6bhp @ 3,500rpm. These figures might seem to compare favourably to a Villiers 2F motor, which lists at 2.0bhp @ 3,750rpm (with limiter pin fitted in the carb. Remove the limiter pin and power is raised to 2.8bhp @ 4,000rpm).

Bigger than the 4-inch VEC flatback headlamps with 3-inch reflector and plain covering glass more commonly found on most period autocycles, Excelsior mounts a 5-inch Miller headlamp shell with proper 4¼-inch lens to try and make a little more of the higher rated 21-Watt Wipac ‘Genimag’ set (while our booklet quotes a miserable 9W output produced from the earlier Miller FWX flywheel magneto, with specified bulbs: head 6V/6W, tail 4V/3A).

Instead of the original autocycle seat, which offers a more comfortable supporting area, our G2 was fitted with a small cycle saddle that really didn’t afford quite the same level of luxury.

Late in 1948, Villiers announced the imminent discontinuance of their pre-war Junior De Luxe autocycle engine, to be succeeded by the introduction of new two-speed 1F motor cycle and single-speed 2F autocycle motors.

While many other British motor cycle manufacturers readily adopted these engine types to produce new model autocycles and lightweight motor cycles, Excelsior completely shunned the new Villiers proprietary engine models to stick by their old style S1 and G2 autocycles to support manufacture of their own engines.

Excelsior must have appreciated their marketplace disadvantage for several years, but it wasn’t until Villiers replaced the 1F with a new two-speed 4F engine in October 1952 that Excelsior finally succumbed and presented its new F4 model Consort powered by the Villiers 4F in April 1953.

The F4 model Consort continued into 1955, when it was joined by a new F4S Consort with plunger rear suspension.

Equipped with Villiers 4F engine with cable operated two-speed trigger change, we’re a little surprised to find our rigid framed Consort test bike coded with frame number F4S/4517, but we guess that’s how Excelsior must have prefixed the serial, and that’s how it is.

Looking round our Consort, the first and most striking impression is what a small bike it appears. The seat seems really low, so getting out the tape measure confirms that it’s just 27 inches from the ground to the top of the saddle and, with the lightweight Lycett, that’s not adjustable either.

Continuing with other basic measurements since we have the tape out, 72 inches (6 feet) nose to tail, and 48 inches (4 feet) wheelbase, so maybe Excelsior just based the bike on nominal Imperial sizes?

The wheel & tyre sizes of 2.50×19 are a little down on the probably expected 2.25(2.50)×21 rims of period 2F powered autocycle brethren, so further contributes to Consort’s slighter stature.

The rear wheel is disposed with both brake drum and main drive sprocket to the left hand side (some light motor cycles fitted alternative hubs with drive sprocket to left and brake drum to right), and in Excelsior’s case connects the foot brake by rod on the same nearside.

The rigid frame is distinguished by widely spaced rails beneath the engine on both sides, and same wide stays up to the saddle post. The front down tube, main spine and central saddle stem are all single tubes, and the assembly is connected by traditional brazed lugs.

Fuel sloshing around the two separated halves of the low-slung conventional saddle tank doesn’t have to cause concern about having to tip the bike over to refill the left hand half with the single fuel tap, since the halves are connected beneath by a balance tube. Pull on the plunger tap, and while we’re just getting a feel for the rest of the controls, our pace bike rider indicates our Consort’s Junior carburettor is leaving a little fuel puddle on the floor … over excitement about the forthcoming test run, or maybe just a stuck float needle? We nudge the flood button, hoping to free this off, then opt for a quick starting attempt without any choking of the air strangler since we’re now concerned that the motor might be flooded.

A couple of kicks and a twist of throttle to give the drowned carb some air soon bursts the motor noisily to life … that exhaust is certainly loud!

After a moment warming the motor to clear while waiting for the pace bike to get started, we pull in the clutch, right-thumb the trigger change forward into first, and ease away up the road. Staying in first to cruise around the corner and down to the junction (blimey, that silencer doesn’t do much silencing!), then notch back up to second (top) as we continue onto the lane. It’s the usual cumbersome 4F trigger change, best not to hurry or it’ll only complain. Change up early and change down late to avoid crunching the dogs. The change trigger is inconveniently just out of reach from the twistgrip, so you have to let go of the throttle, and this ponderous operation engages both hands, so you aren’t going to be making any signals to other motorists while you’re occupied with the gear change.

You soon get used to scowling motorists at junctions.

On to the main street and we gun the motor up to the 30 limit. The exhaust produces lots of impressive noise under throttle, but the resultant acceleration somewhat fails to match its loud advertising … you rather find you’re waiting for the bike to catch up with the noise!

From any disturbed pedestrian who looks around, it’d almost be embarrassing, but you know you can get away with it since it’s so obviously an old timer … Noisy? No mate, old motor bike = diplomatic immunity!

It’s surprising how readily you adjust to the small physical size of the bike considering its diminutive proportions. You’d expect to be conscious of feeling cramped for space considering the footrests are set 8 inches above ground level, so leaving only 19 inches leg height, but the footrests are set a foot forward of the saddle so, despite being low, the riding position is more square-set than you expect.

Comfortable cruising speed settles around 30ish, though generally we preferred to be running slightly over the 30 since the motor didn’t feel to be labouring so much.

The Webb tubular girder forks quiver away up front, doing their job of ploughing a smooth furrow, and the Excelsior frame certainly feels solid enough to ride—it’s planted on the road like a brick outhouse! The generously coil-sprung Lycett saddle absorbs rigid reactions from the hard tail rear frame, and everything seems effective enough within the general performance of the bike.

Turning into a blustery tailwind we tuck into a crouch and urge up the pace to a best on flat of 38–39mph but, try as we might, the magic 40 milestone eluded us on the flat.

No trouble with that barrier on the tucked-in downhill run, dials on the pace bike and our own chronometric matched 45mph into the bottom of the dip. The engine capably handled this new dimension with no fuss or bother, and the cycle frame confidently tracked its course through the dive as though following its foundations. Consort took the fast run capably in its stride, and then charged into the ascent on the other side. Labouring against the incline, the following uphill climb dropped our pace back to 24mph, cresting the rise triumphantly, still in top gear.

Now with the engine thoroughly hot, a brief burst up to max in first attained 24mph, but leisurely riding would be normally be changing up around half that speed.

Lights are worked by a three-position Lucas switch in the 4½-inch headlamp shell. Ahead is off, left position does nothing (presumably dry cell battery parking position, but there is no pilot bulb in the forward reflector), right puts on headlamp for beam–dip switching on the handlebar.

The rear lamp may look like some ‘modern custom’ aftermarket accessory, but is actually an original and period Lucas fitment. Generally, many people may not be familiar with these lamp types, since most manufacturers fitted cheaper Wipac or Miller equipment, and Lucas sets were rather less common on smaller capacity machines.

Many light motor cycles running direct lighting sets typically relied on the old style rubber bulb hooter, and only usually mounted an electric horn for their De Luxe models with rectified lighting and a battery. Our Excelsior however has got round its generator’s low direct output, by cleverly mounting a little, stainless-steel cased electric horn from a later Motobécane moped, and this tiny AC device emits a high pitched energetic screech to unexpectedly startle the unwary.

Cabled from a drive on the front wheel, there’s also a Smith’s D-shape chronometric S531/L-1600 55mph speedometer set fitted, the needle of which clicks away its indications in true clockwork manner. Ratios proved accurately matching readings to our pace bike, so we’re happy with the calibration of that.

Other equipment includes a round toolbox below the tank & seat, with a removable lid thoughtfully disposed on the nearside, so you’re not crouching in the traffic lane while attending to any technical matters with the bike.

There are clips to mount a hand pump atop the chain guard, and the hand pump is there just in case you might fancy some vigorous exercise squeezing a little more pressure in. On the subject of the chain guard, the back face of the guard is thoughtfully extended down with a guard to shield the return run of the chain and prevent the tyre from spraying on water and road deposits. It’s just a fine detail that makes the bike practical to use in all weather, and a trick that other manufacturers could miss in the interest of economy.

Consort only slightly disgraced itself by tiddling little puddles on the floor if you inadvertently left the fuel tap on while not running the engine—just a slightly leaky needle valve seat on the carb float, but seemingly no bother when the bike was running.

The accessory Smiths instrument also mounted an illuminating speedo bulb, presumably of a couple of Watts, though whether this slight additional consumption might have contributed toward to the resultant dim golden headlamp may remain a point of conjecture. We think the dim lights would have probably been pretty dim anyway; this seems pretty much the norm for most of these machines with their medieval generators.

Rather like The Wizard of Oz, Consort’s exhaust volume sounded bigger than the bike. The rider of our following pace bike liked the crisp tone, which particularly emphasised the sharp irregular two-stroke popping as you shut down for the overrun, though did seem a little too aggressive when you were actually riding it. The lack of baffling was further demonstrated as bystanders behind the bike, and our pace bike rider during the test, commented about feeling exhaust ‘pulses’ even 6–10 feet away!

For 1956 the rigid-framed F4 Consort continued with the trigger-change 4F engine, while its F4S plunger-framed cousin initially introduced the new Villiers two-speed foot-change 6F engine. As stock 4F engines ran out later in the year, the rigid-framed F4 Consort also became equipped with the foot-change 6F engine.

Spryt and Goblin engine production ended as the Excelsior S1 and G2 autocycle models were discontinued at the end of the 1956 season due to falling demand for autocycles, which had been dramatically losing sales to mopeds and light motor cycle models for several years.

The F4 and F4S Consort models continued for 1957, and were joined by a startlingly ugly fully-panelled F6S Consort Skutabyk.

The F6S continued on listings for 1958, while the F4 and F4S were both replaced by a new swing-arm frame CA8 Consort fitted with telescopic forks, which also introduced a progressive new year-on-year model numeration system.

For 1959, the sprung frame Consort continued as CA9, while the old rigid frame Consort complete with girder forks returned as a ‘budget model’ F4F, though now employing the ‘standard fare’ 6F motor.

For 1960 the Consorts became C10, and ‘utility’ F10, now with telescopic forks.

1961 continued the Consorts as C11 and F11, from when subsequent ‘changes’ mainly related more to annual model references rather than much effective development. These were tough times in the British motor cycle industry and great names of the past were now dropping like flies.

Production of the Excelsior Consort ended in October 1964, not that Excelsior had particularly wanted to end the model, but primarily because the supply of 6F engines had become exhausted since Villiers had discontinued the motor in the early 1960s.

Excelsior manufactured its last motor cycles in 1964. The business folded in 1965 with its trading name and assets purchased by Britax.

In an exercise harking back to the Corgi compact for its ability to be stowed in the boot of a car, Britax briefly revived the Excelsior name in the late 1970s for a miniature fold-up machine factored from Italy.