The scene was set by the publication of the news of Dick Ostler’s 25cc Mini Auto roller drive cyclemotor model engine in the Model Engineer magazine edition 20th January 1949, and the UK’s cyclemotoring boom was subsequently carried along by an increasing demand for economic transport in the immediate post-war years.

By the end of 1949, production cyclemotors were already beginning to appear for sale on the commercial market, the GYS, Mosquito, Trojan Mini-Motor, and Britax announced its concession to import the Ducati Cucciolo.

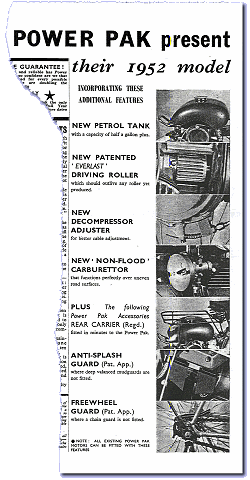

A new Power Pak 49cc clip-on cyclemotor was introduced to the motor cycling press in April 1950, price listed for sale at £25, and offered by Sinclair Goddard & Co. Ltd. 162 Queensway, Bayswater, London SW2.

Considering this cyclemotor would remain on sale for a decade, apart from the published adverts and literature, it’s quite remarkable that practically nothing is known about the people that actually produced the kits!

First announcements of the cyclemotor referred to both Power Pak Engineering Co. Ltd, and presented Sinclair Goddard as ‘sole concessionaires’ and ‘distributors’, suggesting this arm of the business might have been created for marketing the kit, and possibly wasn’t the actual manufacturer.

Sited just down the road from Whiteley’s department store, the 162 Queensway, Bayswater address is now a DIY Tool Store, and the area is mainly given over to retail and housing.

In Sinclair Goddard’s day it’s likely that the ground floor was arranged as a showroom with offices, and probably some workshop facilities for light servicing. Given this site is little more than a relatively small shop with flats above and behind, it would seem rather unlikely that the premises were used for the actual manufacture of engines, so it appears the cyclemotor kits were being made somewhere other than Sinclair Goddard’s registered address.

A Motor Cycling edition of 14th Dec 1950 gives some indication of the man behind the business, where an article on Power Pak reports in the text ‘Mr. H. Easton as Managing Director of the concern which now manufactures this little unit in London’.

When you take one of the units apart there’s no question regarding the nationality of its primary components, British manufactured bearings, a Heplex piston, Wipac magneto, and Amal carburettor—everything is clearly of UK origin.

General arrangement the Standard model Power Pak changed very little over the years, though there were several development improvements, mostly introduced throughout 1951, as minor problems came to light. The original models had a screw-in end to the crankcase allowing access to the big-end bearing, but from engine number 6751 this crankcase door was replaced by one held by three studs.

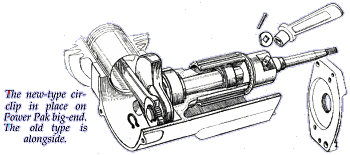

The big-end itself was held by a circlip which, if not properly fitted after an overhaul, could come off and drop into the transfer port, damaging the piston and cylinder. A modification of a heavier circlip was introduced on engine 9501. If dislodged this would seize against the crankcase end, stopping the engine before anything more serious happened.

Other variations concerned the petrol tap and pipe, though this was mainly because of supply problems rather than design improvements.

There were also two types of crankcase oil seal, drive roller and magneto mounting plate; in all cases the two types were not interchangeable.

Some Power Paks were built with a steel con-rod instead of the standard alloy one. Again, these were not interchangeable and the crankshafts they were fitted to were different too.

During the year, the cost of a Power Pak kit increased to £26–5s (25gns), and a text passage in 1951 reported that Sinclair Goddard & Co Ltd was chosen by the Council of Industrial Design to exhibit the Power Pak at the 1951 Festival of Britain. Power Paks were shown at the South Bank, and also included in the travelling exhibition that subsequently toured the country.

1952 saw the introduction of a Wipac Series-90 magneto with lighting coils and a new design of roller, known as the ‘Series-B’. Also, the ‘third-position emergency notch’ disappeared at about this time, which had been intended for use when the tyre pressure was low and no pump was available, but several owners found its extra pressure useful for overcoming roller-slip in the wet; however using the ‘emergency notch’ on a fully inflated tyre would eventually damage the main bearings, so it was removed.

The original direct-drive Power Pak cyclemotor continued into 1953, at which point it was re-titled as the ‘Standard’, and was joined by a new model ‘Synchromatic’ clutched version priced £27–6s–0d (26gns). The Standard model was now slightly reduced in price to £25–4s (24gns), so the Synchromatic represented an extra £2–2s (just over 8% more).

The original ‘Synchromatic drive’ was a system that operated the clutch by the same control as the throttle, where rotating the twist grip first engaged the clutch, then opened the throttle. Outwardly, the new Synchromatic model looked very much like the Standard Power Pak but was finished with a polychromatic copper-coloured fuel tank to distinguish it.

Once again, further modifications occurred in production, where there were two designs of clutch and roller, one with six locating teeth and one with four teeth.

Further detail improvements were reported at the end of 1953. For the Synchromatic there was a new twistgrip which incorporated a fingertip tick-over adjuster. Tick-over adjustment had proved a problem on earlier Synchromatic models, since the carburettor setting which gave a reliable tick-over could often result in a rich mixture (and four-stroking) at normal running speed. For the Standard models, having a reliable tick-over didn’t arise as an issue, because the engaged drive meant the motor never ran unloaded at low revs.

With a new claim of modified porting to improve engine efficiency, the clutch-less model soon became re-titled again as the ‘New Standard’ and now was fitted with a twistgrip throttle control.

1954 saw the listed price of a ‘New Standard’ dramatically reduced to £19–19s (19gns), while the Synchromatic continued at the same cost of £27–6s (26gns).

From August, the New Standard model was fitted with a BEC (Bletchley Engineering Co.) carburettor in place of the Amal instrument, and a further change to the New Standard toward the end of the year introduced a new fuel tank with a rib running all the way round the outside, which was not as elegant as the previous ‘smooth’ design, but cheaper and easier to produce.

Power Paks choice of fuel tank colours being offered at the 29th International Cycle and Motor Cycle Exhibition in November 1954 now extended to two-colour spotted designs, and it was announced that 1955 models could now be offered in colours to match any cycle on the British market. Meanwhile the price of the New Standard marked up to £24–2s, though the Synchromatic again remained at £27–6s.

Our Power Pak ‘New Standard’ displays engine number L36373 dated 1954, and fitted on a 23-inch Gent’s crossbar Raleigh frame 616970P dated to 1948, finished in original green, and seems to have come fully appointed with all the period features: rod brakes, lockable forks, a three-speed Sturmey-Archer Dynohub, stainless spokes, a cycle lighting set, and leather Brooks saddle. The bike however shows its years, the cycle frame being scruffy, rusty and weathered, but proudly wears its history with genuine soul.

The Power Pak engine is fitted with a Wipac Series-90 magneto set (with lighting generator coil), BEC carburettor, and a ‘seamed’ fuel tank in original standard cream finish. Normally the BEC carburetter relies on a ‘lift’ type enrichment mechanism to flood an auxiliary chamber for starting, so simply employed a plain air filter. This machine however has been further fitted with an Amal air filter, which gives an additional strangler shutter action that the BEC wouldn’t normally have.

The engine is operated from a Bowden dual-lever decompress/throttle control on the right handlebar, with the short (top) lever working the decompresser by cable to the cylinder head, and the larger (lower) lever raising the throttle slide.

A push-on/push-off type blade tap sits at the bottom right front of the seamed fuel tank but, because of the location of the fuel tap close against the engine mounting casting, you can push-off the tap, but you can’t get your finger round behind it again to push-on. Consequently you have to grip the head with your fingers and pull, which may not be so easy with gloved hands, or new sealing corks in the tap making the blade action tight.

It’s easiest to engage the drive lever before you start, then trim the decompresser lever on, and navigate to the launch pad with the motor turning over. As the motor spins, we think it sounds a little noisy on the main bearings, so we’re a little apprehensive.

We tug the flood/enrichment spring, pedal off, and drop the decompresser, down the road a little, turn and back, but not a peep. Next we choke up the strangler and try again, now with occasional pops, down the road a little, turn and back, but now it seems too rich? Finally we decide to open out the strangler and go again, a few pops, keep pedalling and throttle-up, then the engine gargles into life and takes over.

We take a couple of turns up and down the road to get a feel of tractability on turns with the throttle down, and it seems quite good despite the motor being cold. If the turn feels too tight to take under power, then you just tweak on the decompresser lever and gently cycle round, then ease off the decompresser and throttle on again after the turn. It‘s all easily manageable this way, and there’s a pleasant popping tone coming in from the exhaust as the engine takes up.

How does a motor that sounds so rough when it’s not running, manage to sound so smart when it goes? The engine is docile and tractable, it seems really quite nice!

The crisp popping note flattens out to a mellow drone as it pulls under load in response to tweaking on the throttle lever, and our pacer eases into formation behind, so we throttle-up and go for our test ride up the lane.

Since the skinny 26 × 1? tyres don’t offer much pneumatic effect, the bumpiness of any rough road surface comes hammering through to the rider as the speed increases; the rigid cycle forks are quite unforgiving, and Mr Brooks’s leather saddle soon reaches the limit of what its basic springing is likely to absorb. Turning onto the main straight, and noting the conditions are still, so wind direction won’t be a factor to consider today, we cruise the outward leg to work some heat into the engine in preparation for a full-throttle return run.

This seems all very pleasant, riding by the hedgerows and fields on a sunny day, with the exhaust gently gargling away behind.

Reaching the end of the straight, the road both ways is clear, so we throttle down to gently pedal-assist our turn around in a wide circle at the junction, then throttle back up and Power Pak takes over for our blast back down the one-mile straight.

Our ‘Standard’ levels out at a paced top speed of 24mph on flat in still air, at which it seems difficult to tease the motor any faster since the North Road pattern pullback handlebars aren’t so conducive to adopting much of a crouch position.

Starting in 1950, early Power Pak engine numbers had no prefix letter, with the series probably starting from 1000+, and running up to around 20000.

An L-prefix was added to Standard model direct-drive motors in 1952, with the new series restarting from 30000+. Starting of the L-prefix was probably an indication that development of the Synchromatic version was underway, and might anticipate some ready means to identify the different crankcase types.

When the Synchromatic was introduced in 1953, its different engines were identified by an S-prefix, with the new series starting from 50000+.

Standard L-prefix motors became OL-prefix around the 41200 mark in 1954, but continued the same numeration series.

Synchromatic S-prefix motors became TS-prefix around the 62800 mark in 1955, but continued the same numeration series.

The Synchromatic TS-prefix motors dropped the S to become a plain T-prefix around the 64130 mark around 1958, and again continued the same numeration series.

The highest ‘Standard’ OL-series prefix recorded so far is OL45181 so they never reached to 50000 where the S-series started.

While the L & S prefixes were obviously introduced to distinguish the Standard motors from Synchromatics, there seems no identifiable purpose of adding the O to the Standard prefix, adding the T to the Synchro prefix, or removing the S from the TS-prefix.

Our Synchromatic Power Pak with engine number S56788 is also dated at 1954 and is mounted in an almost identical 23-inch Raleigh gent’s crossbar frame 744468P dated to 1949, and fitted with a FG 4-speed Dynohub.

The method of operating a Synchromatic Power Pak changes appreciably from the relatively clumsy roller drive cyclemotor engaged engine, which has to stop when the bike comes to halt, then be restarted, to something more akin to a manually clutched moped.

The clutched engine differs in other aspects beyond the clutch, since its aluminium cylinder head doesn’t have a decompresser like the ‘Standard’, because there’s less likelihood that you’re going to need one since you don’t need to stop and restart the motor so frequently like the direct-drive version.

The lack of a decompresser also offers a cleanliness advantage since the valve was always a constant source of oiliness from the inverted cylinder.

Our Synchro doesn’t have the twistgrip operated Synchromatic control, but uses a conventional grip-lock clutch lever on the left-hand bar, which latches into disengage when pulled in, while the throttle is operated by separate rotary lever on the right-hand bar.

The lack of the Synchromatic dual-control device does mean that you may find you have to throttle down and latch-in the clutch lever before you can get free hands to start pulling in the brakes, so leaving a ‘breathing space’ ahead soon becomes a natural instinct.

Starting is different without the decompresser: you pedal off with the engine de-clutched, and then when you’ve built up speed, drop the clutch to get the motor spinning and keep pedalling till the motor starts.

The heavy inverted iron cylinder with deflector top piston is specified as 39mm bore × 41mm stroke for 49cc, with a single transfer port up the back of the cylinder, exhausting direct into a backwards facing silencer.

The Amal carburetter is backwards facing, with an air filter strangler which is quite difficult to operate from the riding position by groping behind you when you’re not familiar and confident with the bike. Once you get used to where it is, and which way it switches, then it becomes more possible to operate its shutter from the saddle.

The exhaust note gargles along at low speed, but doesn’t give you much impression that it’ll get up to high revs, and it doesn’t really. Deflector top designs are invariably rather like that, and generally tend to deliver their best efficiency at lower revs.

Opening up the throttle lever and building the motor up to speed, it plods steadily along, solid and relentless with a flat drone emanating from the silencer.

Our Power Pak Synchromatic clocked a maximum of 27mph along the flat, paced by Sat-nav.

The dry plate clutch works well and does prove useful in operation, in that you don’t have to stop the engine at junctions or in traffic queues, etc, so the Synchromatic becomes a much more practical machine to use around town.

The Power Pak feels rather like a commercial truck of the cyclemotoring world—unspectacular, but relentlessly slogs along to dependably get to its destination.

The Synchromatic continued with the Amal carburetter and the seamless tank for a while, presumably using up stocks of these items, until a service bulletin in 1955 notified revision of the seamed tank incorporating simpler mountings, and at the same time, the cast aluminium lifting handle at the back was changed to a smaller plate.

Synchromatic models subsequently appear to have adopted the seamed tank and BEC carburettor from somewhere around engine number TS63500+.

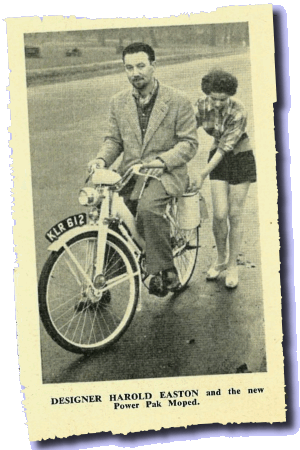

A forthcoming discontinuation notification of the Power Pak cyclemotors was reported in October 1955, and seemed prompted by the announcement of a new Power Pak Moped, which the Motor Cycle magazine credited to Sinclair Goddard of 162 Queensway, Bayswater, London W2. Its rival magazine Motor Cycling, presented a similar report credited to Power Pak Engineering Co. Ltd, of Coventry, and further related that ‘production of 1,000 machines a week of the new Power Pak Moped is envisaged, thanks to the acquisition of a large and modern factory in Coventry’.

This Coventry address can be found in an earlier announcement in Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader edition 20th August 1955, that dealers should send small repairs (bearings, magneto & carburetter service, etc) to 162 Queensway, and larger jobs to Longford Works, Black Horse Road, Longford, Coventry, so this might seem to be the ‘new premises’ also referred to in pre-Earls Court Show Power Pak Moped advertisements.

The timing of these announcements at the end of October was in preparation for the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show from 12th–19th November, where all three Power Pak models were exhibited on stand 19 and, for the first time, the price of the Synchromatic unit had been increased to £33–11s, while the New Standard would now cost £28–7s–10d.

The new Power Pak Moped display machine was equipped with further accessories of a pillion seat mounted on the rear carrier and footrests bolted from the rear wheel spindle. A price of £54–17s–0d was given for a ‘Standard’ Moped, and £64–15s–0d against a De Luxe version, though quite what might be intended to comprise ‘included fittings’ or ‘further accessories’ wasn’t exactly clear. The Power Pak Moped’s frame ‘carry handle’ was a very typical continental feature and suggested that the cycle chassis was unlikely to hail from any British manufacture … it wasn’t! The frame, assembled complete with the fork set was offered for sale as a proprietary kit by Italian manufacturer Casalini, and presented in a 1952 edition of Moto Revue, while the engine was the Itom Tourist roller drive cyclemotor unit, which was already listed in the UK 1953–61 as a clip-on kit, and imported by Itom concessionaires: Adimar, 222 Brixton Road, London SW9.

The prediction however proved somewhat premature because the Moped was destined never to reach production, and in January 1956 a further announcement from Sinclair Goddard confirmed an about-turn, that the Power Pak cyclemotors would continue in production.

No one really knows quite what or who Sinclair Goddard may have been, since this appears as no more than a faceless, shadowy name, connected with nothing but the cyclemotor and its associated accessories. There appear no other references to this company, either before or after the cyclemotor, and no association with any other product.

Just the tiniest clue about who may have been the leading figure behind Power Pak can be found in Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader edition of 26th November 1955, presenting a picture of ‘Designer Harold Easton and the new Power Pak Moped’, and it’s notable that the young lady pictured with him also appeared in a number of the publicity pictures, wearing the same clothes, so we can probably conclude these shots were all taken on the same day.

It seemed that Mr Easton wore a few hats, and was fairly influential around the company.

There are also period text entries referring to Bruno Fargion moving from Sinclair Goddard (Power Pak) to Dunkley at Hounslow, and credited as designer of their two-speed, four-stroke motor series. Since the first 46cc Mercury Mercette version of the Dunkley engine also appeared at the very same Earls Court Show as the Power Pak Moped, it might seem that Mr Fargion had probably gone to Dunkley before 1955.

The timings of these movements are such to suggest that Bruno Fargion was probably responsible for the Power Pak Synchromatic clutch model design, though whether his term went any further back to the original cyclemotor engine design is unclear at this time.

The Italian designer would certainly seem the most likely connection between Power Pak’s Managing Director, Harold Easton, and the Casalini frame kit for the Power Pak Moped, and it might appear more than co-incidental circumstance that Dunkley’s first S.65 scooter announced on 30th January 1958 was also based upon Casalini chassis components.

It has to be concluded that Bruno Fargion must have had some positive connections with Casalini, and probably suggested the Casalini frame kit to Harold Easton for the Power Pak moped, but had already moved on to Dunkley by the time the Power Pak Moped appeared.

Subsequent to its Earls Court Show debut on 12th November 1955, the Power Pak Moped further appeared in 1956 trade listings, though only posted at a single model price of £56–12s–6d (presumably for the ‘Standard Moped’), but there is no evidence that any production models were ever made or sold.

There were no further references to the Power Pak Moped, though quite why the project failed has never been wholly clear.

There wouldn’t seem to have been any sales cost issue, since the basic Power Pak Moped was competitively priced, with only the Norman Cyclemate and the Mobylette Standard being listed cheaper.

It appears most likely that in attending the Earls Court Show in 1955, Mr Easton noted the increasing selection of newer geared and chain driven mopeds presented by other manufacturers, then probably appreciated limited prospects for his new roller direct-drive ‘Moped’, and that marketing this largely factored machine to replace the Power Pak cyclemotor range was going to be pretty pointless.

The Power Pak cyclemotors continued in 1956 trade listings, both with their prices increased as previously notified at the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1955, the New Standard listed at £28–7s–10d, and Synchromatic at £33–11s–0d.

Toward the end of the ’50s, the cyclemotor market was rapidly dwindling, but the Power Pak continued to be available until 1961—one of the last three cyclemotors on the British market (Cyclemaster and Itom being the other two).

Both variations of the Power Pak cyclemotor remained on trade listings throughout the 1961 season, but failed to return for 1962.