In 1960, Jack McCormack (as the first national sales manager of American Honda Motor Company), noticed that the Honda dealership of Herb Uhl in Boise, Idaho was selling more 50cc Honda CA100s than the combined total of all six dealers in Los Angeles! (The original Japanese C100 model had a single saddle and indicators, but the US market CA100 differed by having a dual seat, but no indicators). Jack discovered the dealer was selling its CA100s as a conversion to trail bikes by the fitment of knobbly tyres for better off-road traction, and a second rear sprocket with more teeth to reduce the final drive ratio. While the larger sprocket increased effective torque at the rear wheel for a lower top speed, Uhl claimed that in comparison to traditional big trail bikes that could be difficult to handle, the combined advantages of light weight and the automatic clutch particularly appealed to unskilled riders to enjoy off-road riding.

McCormack shipped a version of Uhl’s customised CA100 to Japan, with a request for Honda to create a production version, and by March 1961 a factory Honda CA100T Trail-50 model was completed for supply to the US market—and proved a North American sales success!

The Trail 50 was further modified with other changes leading to the creation of specialised versions for hunting and fishing by the addition of a rifle or fishing rod holder, and the naming of specific models as the Hunter Cub and the Fishing Cub, leading onto the 1962 55cc CA105T Trail-55 with high-level exhaust. The CT200 Trail 90cc four-speed motor cycle, made 1964–66, technically became Honda’s first CT-series machine, by fitting the 86.7cc OHV engine of the C200 motor cycle into the step-through Cub frame. There was also a CT200 Hunter Cub in 1964, where the motor cycle four-speed manual gearbox had been replaced by a three-speed semi-automatic shift in the manner of the original C100 50cc Cub, and this model was further taken as the basis to develop the first CM90 step-through scooterette in 1965. The CM90 was replaced in 1966 with the 89.5 cc ohc CM91, which received restyled forks and headlamp along the lines of its smaller C50 cousin (4.8bhp), to evolve into the now more familiar C90 (7.5bhp).

The strength of the C90’s extra capacity and power output lent itself better to a number of ‘special applications’, including a new overhead camshaft CT90 model to replace the CT200 Trail. The CT series prefix primarily relates to a group of different ‘Cub Trail’ off-road machines, but would also become further applied to a range of off-road motor cycles 125–250 from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s.

![]()

Our first variation concerns the Honda CT90, produced from 1966–79, which was adopted by the US Postal Service for mail and small package deliveries.

Our model employs the same standard size brake hubs and wheel rims as the road-going C90, but equipped with 17×2.75 trail tyres. The off-road frame is fitted differently in a number of aspects from the road model, with a single pad seat, which tilts from the front for access to the filler cap of the larger capacity fuel tank.

The frame is fitted with a stout telescopic fork set, which looks chunky enough to have been originated from maybe a CD series motor cycle. The handlebars are secured by alloy clamps onto a rotate-able alloy bracket on the top yoke, locked down by securing clip. This is so the handlebar set can be unlocked and turned 90º for compact storage or easier mounting on the back of a camper carrier. The frame down tube is trimmed with a plastic cover, which blends into an air filter box on the left-hand side, with a high-level intake to a box in the front of the rear carrier. The rear carrier is a tube and pressed steel fabrication, 15 inches square, which would normally carry a fibreglass moulded Postal Service mailbox.

A ‘reserve’ petrol tank hangs off the left-hand side of the back, but is not plumbed in, being a simple detachable fuel bottle for topping up the main tank. There’s also a helmet lock built into the reserve tank strap, which doubles-up to also lock the bottle strap. The main drive chain guard isn’t the usual full-enclosure of the road-going C90, but a high mounted single top strip guard for off-road purposes. The right-hand side of the frame has a conventional plastic battery box side panel, and high-level exhaust system. The forward frame is fitted with bolt-on chrome-plated tubular crash bars, from the bottom of the headstock, to fix at the front foot pegs, with a pressed-steel bash plate welded underneath the tubes to protect the lower engine from impacts, so it’s a fairly structural addition once bolted into place.

As well as the rear carrier, the postal service could also fit a front carrier above the mudguard and ahead of the headlamp, which may carry further bags down the front sides, as well as loading the rack. A mid-frame rack could also be fitted, with a carrier on top, and bags down the sides.

For controls, the right handlebar lever just works the front brake, and a right-hand footbrake works the back brake, so you’d think the left-hand handlebar lever would operate a manual clutch—wrong! It also works the back brake, by a linkage connection beneath the front right-hand side of the swing-arm, and the gearbox is a four-speed foot-change semi-automatic, worked by a heel-and-toe rocking lever on the left-hand side. It’s hard to fathom much useful purpose for this dual operation rear brake arrangement, because the leverage and force advantage of a foot pedal offers much stronger braking action, since you can’t apply anywhere near as much force with a hand lever … and it’s not really as if your right foot has anything else to do?

And why are rear footrests fitted, when there’s no rear saddle? Maybe it’s so the rider can stand on the rear footrests, and still work the back brake with the left lever… but then you can’t change gear with the shifter at the left-hand front footrest? No, it really doesn’t make sense, whatever way you look at it.

Our bike is only fitted with a side stand off the left footrest mounting, though a centre stand was originally fitted, but removed because it stuck out awkwardly and looked out of place. Now the bike always looks cool, parked at a jaunty angle…

Ignition only turns off–on, at top left-hand side of the headstock, with lights independently switched off–low–high on the right-hand bar set. The speedometer indicates up to 80mph (obviously well beyond the bike’s performance, which makes you think it’s an adaptation from something else (a CD maybe?), and marked 20 in first, 32 in second, 45 in third, and 56 in fourth, though this might seem a little optimistic? A second set of markers further shows 10 in first, 16 in second, 22 in third, and 28 in fourth; because the motor is fitted with a Hi–Lo ratio box which mounts outboard of the front sprocket final drive case. The Hi–Lo ratio is obviously 50% reduction, operated by a hand switch on the bottom of the casing, so you have to stop and dismount to change over the gear range.

Fuel turns off–on–res by a lever at the carburetter, low on the left-hand side, and you might notice there’s an additional pull-knob on the carburetter, which enriches the fuel for high altitude use (not much need for that in Norfolk). There’s also a choke lever, but we’re told this motor doesn’t like choke, so just kick and it starts.

Gears select four-down/forward on the rocking pedal, and there’s that characteristic clunk forward as you engage first, then open the throttle and the semi-auto clutch takes you away. Down into second and the four-speed box certainly feels as if it enables a better acceleration, but you need to consciously hold your left hand onto the bar grip or there’s an automatic reaction to be trying to use the brake lever as a clutch … must resist … but it’s so annoying. There you are trying to change gear with a brake lever…

You also find that if you operate the rear handbrake at the same time as you’re using the footbrake you can feel ‘feedback’ at your hand through the linked arrangement, and vice versa through your foot on the pedal. If you had three independent braking systems that could be operated at the same time, then that might make some sense. Some Cyc-Auto models and the HV Powell Joybike were examples that employed three independent braking arrangements, as back brake, front brake, and a transmission brake. The Raleigh RM1C and RM2 moped had a linked rear braking arrangement, in that pulling on the right-hand front brake also operated the back brake by the same lever. That was to purposefully give you better braking while you pulled in the manual clutch and locked it in with the flip latch, so you could then release the clutch lever and pull on the left-hand rear brake lever, then feel the extra braking force coming in as you applied more force with the second hand lever. Maybe the CT was supposed to benefit from a lighter hand braking option for off road use? But then every other geared trials bike manages perfectly well with a single footbrake … sorry Mr Honda, but this was a real dead-end idea.

The high-level exhaust is a proven and practical fitment for off-road use, and presents a crisp popping tone to the rider at lower revs, rising to a slightly angry snarl as the revs get up. The exhaust plays nice tunes for the rider, while the silencer makes it un-intrusive to pedestrians—an ideal combination!

Wringing the CT90’s neck, catching a strong tailwind on a downhill gradient indicated a best of 50mph on the speedo, though our pacer only clocked 47 on the sat-nav. It does take time to build the 90 up to speed because of the bike’s weight and its power to gearing ratio. Maybe given a longer downhill straight you could probably tease a few more mph above our top speed, but it’d seem pretty unlikely you’d see the marked 56 in fourth. The CT didn’t feel as if it would pull a higher ratio, so the end of the speeds-in-gears line looks like it was ‘projected’ rather than reality.

Stopping and switching over to the low ratio, finds the 50% reduced range really low, so absolutely not suitable for any on-road applications, but it does allow this small capacity engine to be more capable in off-road applications where it wouldn’t normally have the power to cope, and it does make the bike more controllable at lower speeds.

Electrical systems were 6V back in the early days, and the CT90 inherited the same equipment as its road going C90 cousin. CT90s could be equipped with indicator sets, with a left–off–right switch built into the left-hand bar set, and winker circuits integral in the standard wiring harness, but this US Postal Service version never had any fitted.

For a relatively small capacity motor cycle, the CT is certainly a heavy lump to manhandle. You really feel the weight of all the bolt-on additional steelwork that this Postal Service bike has to drag around and it could be a harder lift than you might expect when loading it onto the back of a camper carrier rack.

The CT90 ended production in 1979, to be replaced by the CT110 in 1980. This was basically the same machine with its capacity increased to 105 cc, though it initially lacked the reduction box; however this was returned for following production. CT90 models were never sold in the UK, but the road-going step-through Honda CE90 was sold from 1967, and listed up to July 1977 when it was replaced by C90Z2 listed from May1977, and then re-designated C90ZZ in May 1979. In 1982, Honda uprated the electrical system from 6V to 12V, introduced CDI ignition and changed the model designation to C90C from March 1983, until that was de-listed in February 1984 to be replaced by C90E.

Restyled Cub models were presented in 1984, with a square headlamp for the UK market, plastic-covered handlebars, and a plastic rear mudguard, though the Japanese home market Cub models retained an option for the traditional round headlamp or the new square style. Confusing the ongoing model changes, the C90E was joined by the C90MF from April 1985, and then both models re-designated C90G and C90MG from September 1986 onwards.

![]()

While the US Postal Service adopted the CT90 to suit their own particular needs, the Japanese Mail Delivery Service evolved and specified their own unique MD90 version for use in somewhat different conditions.

While Honda supplies the MD90 direct to post offices across the whole of Japan, it is a model that is not available for retail on the Japanese market at all, since after a couple of years, their contract replaces the bike, and takes back used ones for refurbishment, disposal or resale abroad. MD90s discontinued new production some years ago, and they are being steadily replaced in service with a newer C110MD Mail Delivery model.

Our MD90 model is dated at 2006, and was produced way beyond the date of the C90 that it was derived from. Its most obvious and distinctive feature is the unusually small diameter 14-inch wheels & tyres, though they’re also exceptionally wide at 2.75 inches. Also, the headstock mounts a telescopic fork set, with cast alloy slider legs and particularly long stanchions, because of the small 14-inch wheels. Since the small and wide front wheel and telescopic fork arrangement excludes the fitment of the usual lightweight plastic C90 front mudguard, the wheel is instead covered by a robust steel mudguard with steel brackets.

The seat is held down with rubber suckers, so you have to give it a firm pull to lift. Fold up the saddle from the front to access the fuel cap, with a mechanical fuel tank level indicator set in the top of the tank. The fuel tank is the same type as the CT90, being wider on the sides for a larger capacity, and topped by the wider foam single saddle, though now with a plastic moulded base (replacing the earlier steel pressing), and fixed at a height of 30 inches.

The front carrier frame is specifically designed for this MD90 model and made to mount on the front fork set, though it isn’t actually intended for parcels but carries a Mail Delivery letter bag, which would hang on hooks either side of the headstock. The 15-inch square rear carrier frame also has an extension tube form to protect the rear light from backing into walls, etc. Standard mail delivery equipment was a red-polythene expanding rear carrier for parcels, with a cargo net, so intended to accommodate quite bulky loads. The rear carrier frame also has a right-hand handhold on the left-hand side to help lift the bike onto the centre stand. The MD90 is both clumsy and very heavy to handle, and would be a lot heavier again with a full load of mail, so the lifting handle is really needed—but how does a left-handed postie manage? Clearly longer than the normal C90 centre stand with just 8-inch legs, the MD90 stand is taller with 10-inch long legs, which we measured for comparison.

Because of the weight, it’s generally much easier to use the heavy-duty prop stand, which is attached by a very substantial mounting plate bolted to the left-hand rear swing-arm.

The rear shocks are also special heavy duty units, having an extra 25mm length over the standard C90 units, to keep the centre stand height right with the small wheels, and presumably to accommodate possible heavy loading of the rear carrier.

The handlebars are clearly purpose-built for this special application, and carry the front indicators on welded brackets. Parts of Japan can become very cold in winter, so the luxury of heated grips comes as a standard fitment, with a ‘Grip Heater’, and ‘Off–Lo–Hi’ temperature control. The control switches are plain and simple, marked ‘Turn’ and ‘L/R’ on the twistgrip side, with horn button marked ‘Horn’ and ‘Lights–Hi/Lo’ on the left-hand bar set. Perhaps surprisingly for a special Japanese market model, all the control fittings are indicated in English! The front brake has a parking latch, so you can set it ‘on’ to act like a handbrake on a car.

MD90 side panels are larger than the normal C90 and CT90, so they overlap the rear mudguard arch. This would ordinarily mean the side panels would be open at the back, but the back corners are in-filled with blanking sections.

Though the MD90 ohc engine is the old C90 type with the large clutch casing (which was normally 6V), this version is 12V, but maybe surprisingly for a bike that seems to have every available special feature and more, the motor is not equipped with an electric start, so is kick-start only. There’s an Exhaust Gas Regulator circuit routed from the exhaust port in the cylinder head, which we don’t recall seeing previously on this engine type?

The speedometer is calibrated in kilometres up to 85mph, with 1st→25, 2nd→50, 3rd→80.

Our bike has been geared up from 14 teeth to 15 teeth on the front sprocket, which was primarily intended to just drop the revs for more comfortable cruising, but could have slightly increased the top speed up to a further 2mph under favourable conditions. The 15-tooth front sprocket runs a heavy-duty 428 (1/2"×5/16") chain, which would be a serious upgrade for a standard C90, but the MD90 sprockets and chain are up-rated because of the heavy loads it’s intended to deal with.

The change pattern is three speeds, semi-automatic, all forward/down, with heel-and-toe rocking pedal shift.

Fuel turns on at the carburetter; pull on the choke, a little throttle, and the motor fires up within a couple of kicks to a subdued exhaust puff-fuffle. Click into first with the expected little forward lurch, and then open the throttle for the automatic take-off. Throttle down and click into second, and the bike snatches again as you throttle back on. With these semi-auto gearing arrangements, changing up or down is rarely a smooth operation unless you pick the revs just right and train yourself to ease in the throttle. It’s just a game you can play to while away the riding time around town … and warming up the engine in preparation for our top speed run paced on the sat nav.

On a long and shallow downhill section with a light tailwind, we saw 80mph indicated on our speedometer, and tracked at 53mph by our pacer with the sat nav.

![]()

After Honda had pretty much finished with the original Super Cub themselves, the design was licensed on to the Chongqing Guangyu Motorcycle Manufacturing Co of China (which more commonly goes under the name of Kamax), who subsequently produced a line of motor cycles based on the Super Cub design, including the EEC Super Cub. This Super Cub ‘remake’ was developed specifically for the European market in co-operation with Super Motor Company, which was established as the sole European distributor of the EEC Super Cub, to sell in three different variations as the Super 25, the Super 50 and the Super 100.

Registered in 2011 as a Super Cub KN110-7A, and badged on the front as ‘Super Motor Company’, our low mileage and totally original Cub is really super, with ‘Super’ on the side of the engine, and convinces us it must be super. They really like the ‘super’ word… yes, everything is super!

These Super Cubs were imported to the UK by Urban Rider, 51 New Kings Road, London, SW6 4SE, and the certificate of conformity indicates it was manufactured on 28th June 2010

The rear tyre is a wide section 2.75×17, with the front a more usual 2.25×17, both being the original fitment Yuanxing tyres. The rear rim is marked 1.85 wide and date coded 10.05, and front rim marked 1.6 wide and date coded 10.04. These are wide rims for this type of machine, which make the tyres look even bigger.

The brake hubs look to be 110mm rear and 130mm front, so they’re also larger brakes than its Honda 90 ancestor.

It’s a real surprise to see the retro-look Super Cub fitted with the old style leading-link front forks on such a late dated machine; you’d have thought that generation of engineering would have been left in the past.

The round headlight is 130mm diameter, with a 12V × 35/35W quartz halogen bulb, so another upgrade, and super bright. Plastic is widely used for the cycle fittings, including the mudguards, side panels, leg shields, headlamp nacelle, indicator casings, and rear lamp/rear mudguard assembly.

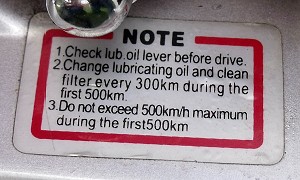

With all the factory stickers remarkably still in place on this 9-year-old machine, we seek to glean what information we can, because researching these Chinese manufacturers can be extremely difficult.

Some of the stickers are printed in Chinese, though others appear to be in English.

Sticker on engine:

1. Check lub oil lever before drive (What? Maybe they meant ‘oil level’, but it does say ‘lever’)

2. Change lubricating oil and clean filter every 300km during the first 500km

3. Do not exceed 500mph maximum during the first 500km (=300mph just running in! Wow, this thing is fast!)

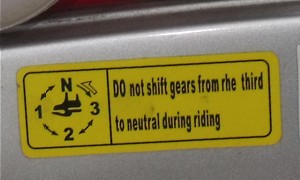

Sticker on chain guard:

‘Do not shift gears from RHE third to neutral during riding’ (Is anyone any wiser from this information?)

With nothing more to gain from further scrutiny, it’s time to go for a super ride.

The electric starter is located above the engine as per the original Honda Super Cub design, and there is also a kick-start. The ignition switch is mounted on the lower right of the steering head set, but there doesn’t appear to be any access to the carburettor through ports in the leg shield like the original Honda, so we presume that our memory of a fuel tap is now just a bygone and figure this Super Cub has evolved to turn on its fuel automatically by vacuum tap.

We do however manage to find a thumb choke trigger hiding beneath the left bar set. Above this, a horn button, indicator switch L–off–R with push to cancel, and on top a rocker switch for lights beam–dip. The right bar set further has a starter button, light switch off–on–park, and a rocker kill switch for the ignition.

We give the starter a spin with a tease on the choke trigger, and the motor ticks into life to the sound of a rattly sewing machine, since the silencer so effectively muffles most of the exhaust noise.

The frame is fitted with a centre stand, but surprisingly no side stand, so nudge off the main stand and onto the wheels.

With the gear rocking-pedal on the left-hand footrest, click forward/down into first, ease open the throttle and the automatic clutch snatches in sharply. The auto-clutch engagement is far too snappy, which makes take-off control most unpleasant, though we believe this can be adjusted to soften the effect.

The Super 110cc motor delivers good torque from low revs, and you can easily lift the front wheel if you snatch on the throttle. Acceleration is brisk as we change up through the gears, and contrary to the chain guard sticker which suggests the bike has three gears, it turns out the motor actually has a four-speed rotary gearbox! The rotary box allows you to change direct from fourth to neutral when stationary, but not when moving, because some internal mechanism blocks the selector in motion.

Calibrated in mph, the Super speedometer proved little more than an approximate instrument, which was difficult to read as the needle only moved over a narrow arc, and its close markings were hard to make out.

Our pacer clocked a best of 48mph on flat in upright stance on the outward leg, and at snarling revs, 54mph on flat and tucked in a crouch on the return leg (indicated around 80km).

The LED fuel gauge built into the speedo is a uselessly random electronic device, flashing from one red, one amber, or any of the six green lamps at its whim, but proved hopeless at conveying any indication of the actual fuel level.

There is a lockable fuel cap under the lockable seat, which seems like double security! Maybe fuel theft is a big problem in China?

The light action drum brakes proved sharp and effective, but did make some complaining noises in operation, and the beeping indicators certainly reminded you that you’d left them on.

With Honda having moved on from its Super Cub, and having licensed out the design to Chongqing Guangyu in China, it was something of a surprise when the wheel seemed to turn full circle in 2017, as Honda re-introduced a new retro-design Super Cub with a return to the traditional round headlamp, and looks very similar to the Chinese licensed machine.

![]()