The P39 Gadabout

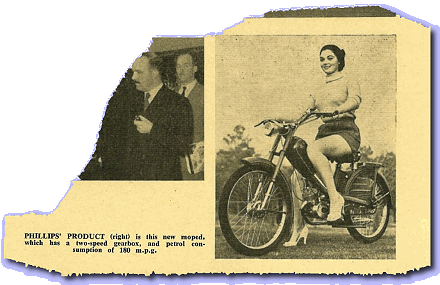

Phillips first presented its Gadabout moped at the Earls Court Show in November 1955, as the P39 model with a two-speed Rex engine. Like the P36X Motorised Cycle that preceded it, the Gadabout was another licensed design from the German Rex Company of Munich, and initially comprised a large percentage of parts supplied by Rex, but Phillips progressively replaced many of its German imported components with UK manufactured parts.

When the P39 was introduced, only the complete front wheel, rear rim, and a few cycle fittings were British made additions. The magnoto set soon changed from Bosch to Miller, the headlamp from Hella to Excelite (which was Phillips’s own brand), the rear hub from Prior to British Hub Co, then mudguards and front forks redeveloped to patterns made from within the British Cycle Corporation. A duplicated frame subsequently was produced by Reynolds Tube Manipulators (another Tube Investments group company), the original 7-pint ‘bubble’ petrol tank swapped for a larger 10-pint ‘teardrop’ tank in October 1956, and was matched with a shorter alloy casting to trim the frame down to the seat post.

In June 1959, Phillips introduced a new three-speed Rex-engined model Gadabout P50 De Luxe, and at the same time began advertising a P45 model Gadabout with the Villiers 3K moped engine, which became listed as available for sale the following month.

Phillips seemed quite late in presenting their P45 Gadabout, because the 3K engine had been introduced by Villiers back in the summer of 1958, and Norman had quickly managed to present its Lido moped with the new Villiers moped engine installed by October of 1958, well in readiness for the start of the 1959 sales season.

Phillips however was in little position to present its 3K engined Gadabout so quickly, since it still had contractual obligations and stock of the two-speed Rex engines, so the P45 could not be introduced as a as a replacement for the P39 until its two-speed Rex motors had been used up. The P39 Gadabout was notified as de-listed in July 1959.

While all the cycle fittings had progressively changed over the preceding four years, the colour had remained the same metallic red, so early Phillips P45 and P50 Gadabouts were finished in the same scheme as the preceding P39s. Its fellow TI/BCC group Norman company also employed the same painting technique on its Nippy mopeds, and the distinctive metallic colour would later be adopted by Raleigh and called Royal Carmine Red.

Finally, towards the end of 1959, the Gadabout colour scheme changed to a black and cream combination, which is the cue for us to present the first of our ‘Twins’.

Fitment of the Villiers 3K engine demanded several subtle changes to the Gadabout: firstly its new Villiers motor required a modified mounting arrangement, and a different profile of the 3K magneto cover meant a new pressing was needed for the bottom chain guard. The 3K engine employed a different exhaust pipe, and its own Villiers silencer, and the engine’s outboard back-pedal brake ratchet required a new form to the brake rod.

Villiers-made throttle, clutch and gear cables were also supplied with the engine, but were not compatible with the German-made Magura controls employed on its P39 predecessor, so Amal provided new twistgrip throttle and gear change sets to suit, which had already been employed on Hercules and Norman mopeds.

Our first Phillips Gadabout model P45 with Villiers 3K engine was registered RGV 552 by the West Suffolk authority in April 1961, and frame number 12N 7090, tells us from the 12N prefix code that Phillips made the bike in December 1959, so this would have been one of the earliest production bikes in the new colours. The new black & ivory scheme however, didn’t seem to have been improving Phillips’s sales against a background of falling demand for motor cycles in general.

That one of Phillips’s latest models took a whole year and four months to sell and register could be some indication how sluggish the trade was in 1960, and probably provides some insight into why Tube Investments began embarking on a rationalisation of its British Cycle Corporation divisions and products around this time.

The Villiers 3K engine with cast iron cylinder is specified at 40mm bore × 39.7mm stroke, with 7:1 compression ratio alloy head for a rating of 2bhp @ 5.500rpm, and fed by Villiers’s own SM10 carburettor with a 12mm venturi.

The crankshaft journal is fitted with an engine speed clutch, which invariably results in accelerated clutch plate wear, and primary transmission is delivered by chain. Since the engine runs ‘the wrong way round’, the primary chain works under loaded tension on its bottom run, allowing the ‘slack’ to drop back into the sprockets on its top return run, so tends to give the engine something of a characteristic ‘running rattle’.

Pull on the Ewarts plunger fuel tap at the bottom right-hand corner of the fuel tank, and watch bubbles dancing in the clear pipe till the float chamber fills. Push down the choke shutter on top of the carb, and maybe a little tickle of the flood button just for good luck. The engine fires up within a couple of spins, but proves reluctant to pick up revs until it’s been warming for a while, so we play with the switches while waiting for the motor to join us… Yeah, the usual yellowy beam–dip headlight, though maybe brighter than we expected, and the Miller horn buzzes OK.

Two-speed gears are hand-changed on the Amal shifter, though forward for first gear isn’t particularly friendly to locate, requiring the grip to be twisted right round and held against the forward stop, until the clutch lever is fully released to engage the gear. Failure to execute this operation securely would inevitably result in the gear jumping out. Changing up, neutral is in the middle and indicated by a small arrow on the body of the casting, which is practically impossible to see from the riding position unless you peer down to examine the control. The shift up to top involves wringing the grip back through neutral, and further round towards the rider through 90° of arc, giving the impression of there being rather too much movement for the purpose of selecting just two gears.

Releasing the clutch lever engages second, which also feels like a big ratio jump, so the revs drop back, and the motor has to labour through a flat-spot to regain its pace. Once the engine has worked back into its power band, the bike settles to steadily cruising on flat in an upright position up to 30mph, and showing a best on flat in a crouch at 33mph.

Downhill in crouch paced at a peak of 36mph, at which the motor was buzzing fairly, but achieved this smoothly and comfortably enough, which was better than we expected.

Due to its relatively low 7:1 compression ratio, the Villiers motor fades away on uphill climbs, steadily dropping down to 22mph on our test hill, but never required shifting down to first against the light incline. Obviously there would come a gradient where a shift down to first would be necessary, but it’d climb most gradients in low gear—just slowly.

The 3K engine feels mellow and unspectacular, but they do just seem to keep plodding along forever.

Our P45 feels light to handle and well balanced, with weights of 3st 4lb front and 3st 10lb rear, so 98lb wet, which compares very favourably against the cumbersome and heavyweight Norman Nippy Mk4 (with the same 3K engine) at 114lb dry. The Gadabout rides very well, handles nicely on smooth surfaces, though a bumpy track will upset the rigid rear frame a little.

The round silver faced Huret 40mph speedo seemed to work initially, though the needle soon started wavering, then swinging wildly, then mostly didn’t work but managed occasional twitches—paramedics would probably report that the patient died during the test run.

Excepting the Excelite headlamp (Phillips’s own make and brand), all the rest of the electrical fittings are Miller, with the Villiers mag-set outputting 6V × 18W to the Excelite 15/15W beam–dip headlamp, 3W Miller tail lamp, 15W Miller horn, and Miller five-way handlebar switch beam–off–dip–horn–cut-out.

It’s nice to see a bike retaining all its correct and original equipment in working order. Even the horn still emits a charming buzz, which politely seems to ask people very nicely if they might care to take note.

The Gadabout P45 became Phillips’s only all-British-made moped, since it was the only machine in its range that employed all British-manufactured components.

Qualifications for the all-British moped club might form a disputed shortlist:

1. Hercules Grey Wolf and Her-Cu-Motor 2, with their JAP engines and Burman gearbox.

2. Powell Joybike with Trojan engine (though the Mini-Motor was designed by Italian Vincenzo Piatti).

3. Mercury Mercette with its Dunkley engine (though designed by Italian Bruno Fargion).

4. Phillips Gadabout P45 with Villiers 3K engine (though the frame originated from German Rex design).

5, 6 & 7. Norman’s Nippy Mk2 /type-2, Nippy Mk4, and Lido Mk1, all with Villiers 3K engines (though all the frames originated from the German Achilles design)

8 & 9. Raleigh’s RM1 and RM2c with Sturmey–Archer engines.

10. The believed extinct Talbot mopeds with original Trojan Mini-Motor and later two-speed Mini-Motor.

11. Reynolds moped prototypes built with Miller moped engines (but no examples are known to survive).

After which the qualification line may be drawn across the Ambassador Moped built with Villiers 3K engine (because the Finnish Solifer Company manufactured the cycle frame which was adapted by Ambassador and equipped with Continental fittings).

Our second Phillips Gadabout model P50 with Rex three-speed engine was registered FJF 707B on 4th December 1962 by Leicester, and the frame number code 4R 1200 tells us Phillips made this bike in April 1962.

The Ewarts fuel tap hangs on the bottom right of the tank, pull the plunger for on, then twist and pull again for reserve.

There’s no flood button on the float chamber of the Bing 1/13/3 13mm carb, since this enriches by a pad choke, thumb the trigger under the throttle twistgrip, while pushing firmly down on a pedal, and the motor generally fires up quite readily. Maybe thumb the trigger briefly once or twice more if the motor threatens to die off, but it soon clears to run without further choke, and is generally ready to make a getaway within half-a-minute.

Pull in the clutch, twist forward to first, and letting out the clutch locks the gear in. Clutching again for the up change goes through first and into second, it’s very noticeable that the hand change selector stops and locates second before you let out the clutch, so the gear goes straight in with no crunching about or feeling for the gear. The up change to third also locates precisely at the top of the box, so you quickly tune in to changing ratio with confidence that the gear is always going to be there without any messing about—this is simply the best moped hand change you will ever ride!

Downshifts are similarly pre-located, but on the down change you particularly notice the gear change only allows you to shift down to second, and won’t let you change beyond into neutral or first in one motion. This is a positive mechanical block in the hand change mechanism, so you have to let out the clutch before pulling it in again to access neutral or first—but there is an override mechanism. This is the mysterious little trigger you work with your left thumb beneath the twist change, and it allows you to change up or down, and go right through the box in a single motion.

The three-speed Rex feels a remarkably torquey motor despite its relatively low 6.8:1 compression ratio, and 40mm bore × 39.5mm stroke for 2.1bhp @ 6,000rpm. The quoted power rating figures given for the original two-speed Rex with its original 12mm Pallas carburettor, modestly never changed to the three-speed motor, despite its much better Bing 1/13/3 13mm carburettor, which represented a considerable improvement in carburetion performance.

The P50 pulls well from low revs in all gears. Generally up changes are around 15 in first and 20 in second, though will run up to 20 in first and just past 25 in second. Switching into third finds pleasant cruising around 25–30mph.

P50 sustains its speed quite well through varying conditions; its torque delivers a good account against moderate winds and light gradients, so with the flexibility of the three-speed gears, proves effective at maintaining a consistent average pace.

The Rex engine is beautifully smooth and quiet running, thanks to the precision machining of its internals, and being all-gear drive with no internal chains. The primary gear train and compact clutch is also what helps the Rex motor to maintain its slim appearance, compared to the bulbous look of the Villiers 3K.

Due to having an alloy cylinder, the Rex engine works out 2kg lighter than the Villiers with its cast iron barrel, which contributes to making the 3K motor weigh 20% heavier.

While the Rex engine runs quietly, the Burgess silencer delivers a deep and loud pulse from the exhaust, sounding particularly nice at low revs, and producing a powerful beat, which conveys the convincing impression of strong motor. Opening the throttle also produces a loud induction draw through the carb intake, its mesh filter obviously having little effect on suppressing its gulp for air.

While the potent induction draw adds to a further impression of strength, its constant roaring on throttle can however become a little tiring after a while.

Our best on flat with a tailwind paced at 34mph, though it was still building up at that point before a car slowed to turn, and our feeling was that it could probably have crept slightly higher … maybe pulled 35mph given a better opportunity.

Diving into the downhill run, the 45mph VDO speedometer that had remained stable throughout our test run, now started bouncing around past the 35 marker, and by the time we went through the dip at full speed, the motor was obviously revving at an unnatural rate. The Rex smoothly handled the higher revs, but clearly didn’t like being in such territory, while the speedo was also protesting by swinging its needle somewhere back and forth between an indicated 37 and 42, which our pacer clocked off at 39.

The following uphill climb found revs slowly dropping away on the ascent, but the torque of the motor again played its part as our P50 managed to crest the rise at 23mph, and still in top gear.

The back-pedal rear brake proves very effective, and requires conscious effort to deliver light control. The front brake also proves quite competent with the machine’s capabilities, so all good in the braking department.

The Excelite headlamp doesn’t seem so excellent, delivering a dull yellow lamp, but that is more likely to be related to a poor output from the generator coil of the Miller FW17 mag-set rather than any fault of the standard rated 6V × 15/15W headlamp bulb. The 3W Miller taillight however manages a red glow at the back.

A new Gadabout Mk-4 was listed from September 1961, but was little more than an economy branded derivative of the Motobécane-based Raleigh RM5, and never rolled down the factory lines at Phillips’s Credenda Works, but was actually built from the Raleigh Works in Nottingham.

Glass’s Index indicated the Norman Nippy Mk3 and Super Lido models as ‘discontinued 1961’, when the Norman factory shut its doors for the last time on 30th August 1961, but had been closed down so quickly that there wasn’t even time to build out some remaining moped stocks, so a small number of ‘unlisted’ Villiers 3K engined Norman Lido’s re-appeared in late 1961 and early ’62, seemingly to use up remaining Lido frame stocks after the last Sachs engines were exhausted. Presumably these had been assembled in Nottingham from leftover parts?

Phillips’s frame number codings suggest that production of some mopeds was probably still ongoing into 1962 at Credenda Works, Bridge Street, Smethwick, as this site was also being progressively wound down, but it’s unclear as to whether the bikes continued to be actually built there, or like tail-end Normans, seemingly assembled from parts shipped to Raleigh Works at Nottingham.

P45 and P50 Gadabouts were both officially de-listed in October 1962.