AMF Gloria

cycle badge

AMF Gloria

cycle badge in

World Championship

colours

Insuperabile—a

marque used by

Gloria

MACFA—another

Gloria marque

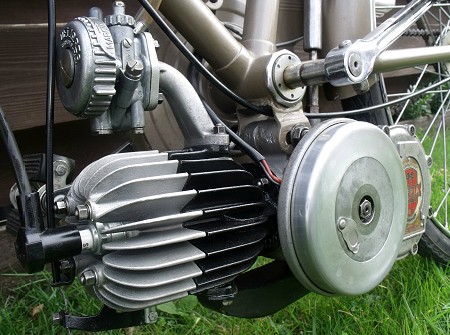

Badge on our

Gloria’s crankcase

Alfredo Focesi was born in Gonzaga in Italy on 6th September 1888. Details of his early years are a little sketchy because it was so long ago, but he initially seems to have helped his brother-in-law Giovanni Gerbi at his Cicli Gerbi cycle workshop in Milan. Giovanni Gerbi appears in period references as a famous road racing cyclist known as ‘The Red Devil’ from the red jersey he wore, and Alfredo had married his sister Artemisia. Shortly after the end of The Great War in 1918, a small cycle business called La Gloria was founded by Francesco Galmozzi, Alfredo Focesi, and seemingly set up and administered by Artemisia Gerbi.

This apparently led to the registration on 18th August 1921, of the AMF Gloria company (Alfredo Focesi of Milan, Gloria Cycles), which was established in a 90-metre square wooden shed in Via Scarlatti, Milan.

A few months later, on November 7th 1921, the National Fascist Party was established, and Alfredo became a fervent supporter and promoter of this new ideology.

Francesco Galmozzi had a significant influence within the early Gloria company, as the cycles became known for their technical, constructive and aesthetic ideas; while a meticulous attention to detail and standard of finish quickly elevated their racing models to an appraised art form.

Exotically decorated cycle frames came to be produced with the Gloria’s characteristic fleur-de-lys lug decorations. It was quite common for the bikes to have fleurs-de-lys budding off the fork crown onto each fork blade; from the head lugs onto the head, top and down tubes; from the seat lug onto the seat and top tubes; and from the bottom bracket shell onto the down and seat tubes, as well as the chain stays. The Gloria badge showed a stylised ‘AMF’ at the top of the shield, with a ‘Gloria–Milano’ scroll across the centre, and a small flower beneath. Such elegant machines were highly regarded.

October 28, 1922 is historically remembered for the infamous ‘March on Rome’, and the following day’s accession to power of Benito Mussolini’s Partito Nazionale Fascista.

By 1923, Gloria had taken over a cycle racing team from Parabiago and with Libero Ferrario becoming the first Italian cycle racing world champion by winning the amateur world championship at Zurich on 25th August 1923. All Gloria catalogues and literature of the period clearly demonstrated a political bias as Focesi openly validated the fascist principles as ideals of both his family and the business.

In 1925 the Gloria racing team again repeated its victory at the amateur national championship.

In 1926, Francesco Galmozzi left AMF Gloria to join another cycle company called Cicli Magri, which he subsequently acquired for himself in 1938 to found his own Ciclo Galmozzi brand and produce his own exotic and desirable cycle frames.

During the same year, Alfredo Focesi transferred the Gloria business in a move from the wooden shed in Via Scarlatti to a new building to serve as a factory-workshop at Viale Abruzzi 58, Milan, within just 200 metres of the Bianchi workshops, which occupied a triangular zone between Viale Abruzzi, Via Plinio and Via Pascoli, with a further extension building between Via Plinio and Via Pinturicchio.

Although the Gloria plant had three display windows facing the street at Viale Abruzzi, in 1927 Focesi opened another showroom with eight beautiful windows on the corner of Corso Buenos Aires and Via Scarlatti, for the sale of sporting and cycling goods, and AMF extended its cycle brands to include the names of Insuperabile, MACFA and Airolg.

Passers by stopped to admire the precious cycling gems on display. Some entered just to browse through the showrooms and handle the exotic racing models.

Fascist leader Benito Mussolini now dictated the restoration of ancient Roman numeration for the years on calendars and, in 1928, Alfredo Focesi appears in the lists that Il Duce published of the ‘fervid assertors of fascism’: personalities of the industrial, political and economic world who were loyal to the fascist ideology. Il Focesi, therefore, features alongside nobles, industrialists, politicians, statesmen and rulers of Italy who supported the regime.

Inter Milan

‘In 1929, the AMF cycle team changed its name to ‘Gloria Ambrosiana’ and wore a new racing strip featuring a grey shirt with a central band of black & blue vertical stripes (in honour of the former Inter Milan football club.’

Why former Inter Milan football club?

Football Club Internazionale Milan was formed in 1908 and the club’s title indicated its ambitions of accepting players from outside Italy. The club’s philosophy was not popular with the Facist regime and, in 1928, the club was forced to merge with the Unione Sportiva Milanese, becoming the Società Sportiva Ambrosiana. The black & blue strip was abandoned and the new club wore white shirts with a red cross.

Presumambly, like most other Inter fans, Alfredo Focesi’s sporting loyalties were stronger than his political loyalties and he showed this in his choice of colours for the Gloria cycling team.

After the defeat of the Facist regime, Inter Milan returned to its original name and colours.

In 1929, the AMF cycle team changed its name to ‘Gloria Ambrosiana’ and wore a new racing strip featuring a grey shirt with a central band of black & blue vertical stripes (in honour of the former Inter Milan football club). This pattern would continue until 1938.

Two more important prizes, the Italian junior championship and the Giro di Toscana, were won by the racing team in 1931.

In 1935 Focesi moved his home, the company headquarters, and the factory-workshop, to a new address just a few doors up the Viale Abruzzi, from No 58 to No 42, while the showroom remained in Corso Buenos Aires. The following year the company’s cycle racing team increased its victories by winning the Milano–Sanremo with Angelo Varetto, the Bernocchi Cup with Enrico Mollo, and the Giro di Toscana with Giovanni Cazzulani, and Giro d’Itala with rider Francesco Camusso.

World War 2 came and, during the allied bombings of August 1943, the Bianchi factory and warehouse buildings in the triangular zone between Viale Abruzzi, Via Plinio and Via Pascoli were practically all destroyed, but the Gloria site just a little further along Viale Abruzzi seemed more fortunate, and was barely damaged at all.

Decisive events for the social, political and economic future of Italy happened over April 28–29, 1945, when Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, was captured and shot.

Finally, as the war ended, Gloria cycles did not return to competition racing, though work in the factory of Viale Abruzzi 42 markedly increased as the bicycle became the most common means of transport in the impoverished immediate post-war period.

Since the Gloria factory remained practically unscathed, it was well placed to benefit from a quick return to production, while many of its former cycle trade competitors were in a less fortunate position.

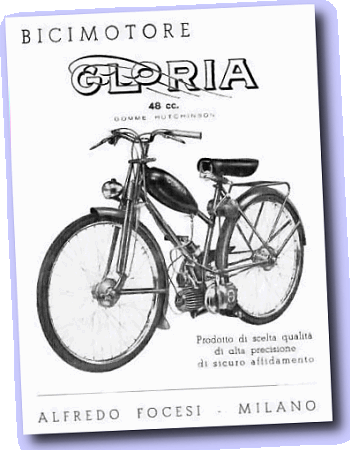

In 1948, and with an increasing public demand for economic motorised transport, Focesi decided it was time for Gloria to develop its first bicimotore (motorised cycle), with a roller-drive engine of 40cc, that could be fitted into their own cycle frame and sold as a complete machine.

This was succeeded the following year by an improved model, having its two-stroke engine and horizontal cylinder with the capacity raised to 48cc by increasing the bore size from 35mm to 38mm, and now rated at 1.1bhp. For the 1950 season, the cyclemotor was joined by a band-sprung frame moped late in 1949. This used the same 48cc motor top-end as the cyclemotor, on a hand change three-speed engine unit, with chain final transmission, and was presented at the Triennale di Milano by Focesi himself.

Other local businesses were also responding to the increase in trade and, by 1950, the bombed out Bianchi plant was rebuilt, modernized and returned to production. Its new works occupied the same triangular site further along Viale Abruzzi, with its office building on the corner to Via Plinio, just opposite the Basso bar.

Bianchi’s cycle racing department was in Piazza Ascoli: just a small workshop with a simple workbench on the right being and, in the middle, two chains with hooks hung from the ceiling to keep the bicycles suspended while working.

Around 1950, AMF Gloria was producing around 25,000 bicycles a year of all types: men’s, women’s and even children’s cycles. The impressive display along the now ten ‘showcase’ windows around the corner of Corso Buenos Aires to Via Scarlatti now included its cyclemotors and mopeds.

In the early 1950s, Gloria was considered to be among the elite of bicycle makes and its finer road and racing models, marked La Garibaldina, were subject to a higher standard of finishing at the frame joints. These were finely finished by careful filing, which took the craftsman three to four hours; the standard market models were normally finished in just half an hour of work.

While it was felt to be the right time for the AMF company to launch this new initiative of motorised products because of the increasing demand, there were considerations that didn’t seem to have been accounted for in the marketing strategy. Gloria’s quality products were still mainly concentrated on the upper end of the market, at a time when, despite a greater affluence beginning to emerge, there was generally insufficient money available for excessive indulgence.

For a medium-sized company like Gloria, maintaining sales would be particularly important to support its investment in motor cycles, otherwise the planned expansion could prove to be the beginning of a decline … Focesi was gambling on an economic boom.

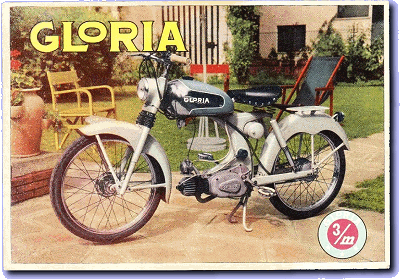

The three-speed moped quickly developed to become the Gloria 3/m in 1952, with pressed steel frame, telescopic forks and swinging-arm rear suspension. This machine was probably the earliest recognisable ancestor of the ‘sports moped’, though performance limitations from its heavy cast iron piston and the 1.1bhp power output from the engine wouldn’t have been particularly athletic. The design however was amazingly advanced considering that many other manufacturers were only just beginning to build clip-on motorised bicycles!

Unfortunately the remarkable Gloria 3/m was destined to remain without any further descendants.

We dated our Gloria cyclemotor at 1952 for UK registration purposes, but at the time it came through the workshops for attention to its motor and cycle chassis to return the bike to running service, we knew practically nothing of its specification.

You don’t come across many of these machines. This is the first complete one we’ve actually seen in the flesh, and probably the only one in Britain.

We didn’t have much information to start with, and it proved practically impossible to find much more, so mostly everything we can relate is from examinations when the motor was stripped.

With a 38mm bore × 40mm stroke, the capacity actually calculates to 45.4cc, which seems to be what Gloria called their ‘48cc engine’. Compression ratio of the radial-fin cast alloy cylinder head is unknown.

The matching radial-fin cast iron cylinder runs a cast iron piston, which gives especially quiet mechanical operation because the common materials have the same expansion rates, so can be run at closer tolerances than an aluminium piston in an iron cylinder. Cast iron pistons do however involve rather more weight, so are generally going to be encountered in only relatively low revving engines. The piston has three compression rings: 38 × 2.5mm C-slot.

Transmission from the crankshaft to the drive is by sprocket and chain within an oil bath case, with no internal clutch, to a final drive by roller.

The extraordinary fabricated steel drive roller seems to be a jig-welded assembly of 35 components, of which 32 are individual teeth! It’s an amazing piece of craftsmanship, and we can’t think that we’ve ever seen anything like it before … and the deeper you get into the Gloria motor the more you become impressed with its exacting standards of engineering. The quality of castings is superbly fine, and all engine fasteners are machine screws!

Starting begins with the usual switching on of the petrol tap, then you’re faced with the Dell’orto T1-10FO 10mm carburettor … which is unsurprisingly marked in Italian. While operation of the flood button on the top of the float chamber may be fairly obvious, markings on the air filter & strangler may not be so … what’s ‘Marcia→ ←Avv.to’? Well you can guess by trial and error, or now there’s internet translators from Italian to English … Avv.to is obviously the abbreviation for something we don’t know in Italian, and Marcia = March, or ‘confine’, so maybe that indicates the choke position?

OK so let’s try a bit of Marcia. Switch the drive lever down to tilt the motor and engage the roller, mount up, pull in the decompresser lever under the left hand grip, and let’s try a pedal … up and down the road, which manages no more than a few intermittent pops and splutters while twiddling with the throttle, but the motor doesn’t want to catch. OK, so we’ll try it again with a little Avv.to instead, pedal up the road with a bit of twiddly throttle, and it burbles into life with a pleasant popping tone from the exhaust.

So there you are: it didn’t want any Marcia.

Gloria gently pulls up to around 15mph before some four-stroking combustion effects start creeping in from inefficient gas scavenging through the small exhaust port. This was a typical feature of many old-time two-stroke motors, where the low height of exhaust ports gave reasonable torque at low revs, but failed to clear spent gas at higher revs, resulting in four-stroke running at speed. As gas scavenging became disrupted at revs, this pretty much represented a cap on the top speed, since the motor wouldn’t rev any higher. As these engines come under load however (ie: going uphill), the gas scavenging improved and cleared to normal two-stroke running, and they generally pull uphill quite steadily as the motor digs in. There is often some improvement to firing efficiency as the motor gets hot, so we run Gloria along a little more to warm up properly.

Coming to the end of the straight for a turn in the road to return to base, we have a go at disengaging the roller by raising the drive lever and throttling down revs so we can keep the engine running through the turn. Gloria takes this operation quite easily, then pedalling up to a light cycling pace in the return direction, we ease the drive lever back down to engage, then throttle up, and we’re underway again … well that worked easily!

As more heat gets into the engine there is a steady improvement in combustion up to a maximum of 20mph, where continuous four-stroke blustering limits further revs, and the cast iron piston begins to induce vibration through the cycle frame, so that really is the best she’ll do. We do try easing back the throttle from full open, to see if we can maybe tease a point at which the four-stroking might abate, but it doesn’t help—that’s just how the motor seems to be.

Heavy cast iron pistons don’t like running up to revs, so the motor is best equipped for steady low rev cruising.

One of the plus points of a cast iron piston in a cast iron cylinder is that use of the same materials mean the tolerances can be closer, which makes the engine both smoother and mechanically quieter, and is exactly the qualities that Gloria demonstrates.

Everything about the Gloria’s cyclemotor displays an extraordinary level of craftsmanship and an exemplary engineering standard of precision. Quality and attention to detail is exceptional and, though the bike isn’t fast, it’s a truly beautiful machine to ride.

Turning the light switch on the headlamp results in illumination at both ends, equivalent to conventional cycle lights, but powered from the internal generator. Both internal coils are linked to jointly act as low-tension generators, with power for the lighting circuit tapped off from the negative (non contact point) terminal of the external HT coil. It’s a very unusual magneto flywheel generator system, and we can only think of one other cyclemotor so arranged: the Vincent Firefly.

In 1953, the range grew with the addition of the Glory 100 motor cycle, a 100cc overhead-valve single with a pressed-steel frame; and another 125cc model with a four-speed transmission, which was further available in Touring and Sport versions. In 1954 the business converted to a joint-stock company under the name of Commerciale Gloria SpA, ambitiously to raise capital for further investment and expansion. For the 1954 exhibition in Milan, Focesi introduced a new 160cc four-stroke engined motor cycle, with swinging arm rear suspension and an Earles pattern front fork.

The choices linked to the expansion of the business, however, failed to return its investments in time because of insufficient sales and, on 21st February 1955, the Milan court declared the AMF Gloria business bankrupt. Production ceased in 1955.

The last racing bike seen at the Corso Buenos Aires showroom in 1956 was fully equipped with the best fittings available at the time: Ambrosio handlebars, Aquila saddle, Pirelli tyres, Universal brakes, with a Campagnolo Gran Sport gear set, and priced at 39,900 lire.

Shortly after, a number of windows in the showroom were panelled over as the stock was sold off, until the display was reduced to just two lights, then finally closed. The factory was shut down, and all the company’s activity was wound up in 1956.

Italy was now in full economic boom, but Gloria was bust.

The level of its business was not structured to support all its activity and investments associated with its rapid transition to such an ambitiously expanded range of motorised products. Delusions of grandeur carried over from the pre-war days of fascism and extravagance had echoed away in the post-war reality, and there was no longer the spare cash or the same demand for such up-market products. Gloria’s beautiful quality came with a high price tag, which ultimately led to its downfall—times had changed.

After a few months, the showroom in Corso Buenos Aires on the corner of Scarlatti, reopened as a great exhibition of furs.

Toward the end of the ’50s, Focesi was drinking at the Picchio bar, behind the central station of Milan, when Francesco Galmozzi showed up. Focesi gestured him over, and apparently, on his knees and racked by remorse, asked forgiveness for the ruin of Gloria, for which he seemingly blamed himself. The day after the events of the Picchio bar, Alfredo Focesi was found near his last home in Via Gasparotto, Milan, having committed suicide with a pistol shot to the head.

Since the closure of Commerciale Gloria SpA, only the brand name survived when a company with plants in Veneto managed to salvage the title to the Gloria name in 1960. Subsequently, following several changes of ownership, the Masciaghi brothers returned the Gloria mark through the Carrefour distribution chain, as a label under the Italian Intramotor brand which manufactured bicycles, tricycles, mopeds and motor cycles from 1976–78.

Gloria Intramotor mopeds with 50cc capacity included the Blanco, Dream, Kid, Scout, Super Scout, Mini Kid, Pinto, Verona, and Gipsy. These were initially equipped with Morini Franco and Minarelli engines, then later with Sachs motors. Motor cycles with 125cc Sachs engines like the 125cc Enduro featured a 6-speed transmission, while the competition motocross Panther was rated at 25bhp with a 7-speed gearbox.

Our second bicimotore (motorised cycle) is actually more of an azionamento a rulli ciclomotore (roller drive moped), but the story similarly starts from an apparently unlikely beginning: on 17th November 1905, as a son is born to a notary at Montecchio Maggiore near Vicenza in northern Italy. Pietro Ceccato completed his education with studies as a medical doctor and started working as pharmacist.

Pietro Ceccato in 1950

In his spare time he played on different musical instruments and was also interested in electronics and technical subjects in general. His first engineering creation was a music stand with a foot pedal to turn the pages. Motor cycling also captured his interest, road racing in particular. He started racing on a Moto Vicentini (a company which later was taken over by Gillet–Herstal) but, with a 350 Velocette, he attracted more attention and Rudge offered him a 500cc racer to run! While the Rudge resulted in a victory at the Italian championship in 1933, he quit the dangerous pursuits of the racing scene following the birth of his first daughter Adriana, and concentrated on music for a while.

Ceccato Romeo micromotore

In 1934, he sold his house to raise cash in an entrepreneurial venture to start the production of office materials, profits from which allowed him to purchase a building area of 10,000m² in the ‘Alte’ district of Montecchio Maggiore. Here he started a factory making any quality products for which he thought there would be a public demand. Abbreviated names were adopted for the titles of the businesses founded there, first FIPA (Italian Factory Pistols and Aerografi) making electric bread ovens, paint spray guns, grease and lubrication equipment, then in 1938, MAPA (Garage Equipment Machines), producing service station accessories, hydraulic rams, and assembly of engines for a number of different applications … until World War 2 interrupted proceedings. Immediately after the war was over, Ceccato started making air compressors, hydraulic car lifts and other garage equipment.

In the immediate post-war period the recovering Italian economy quickly developed a need for a cheap means of motorised transportation, including Ceccato’s own employees who wanted a more practical way of travelling to work than a bicycle, so Ceccato produced a cyclemotor. The first model in 1947 was a 38cc two-stroke attachment engine with roller drive, mounted above the rear wheel, and fitted onto a sporty cycle frame finished in sparkling red. Most of these early ‘Romeo’ cyclemotors were sold to Ceccato’s own workers. A second model of Romeo cyclemotor followed in 1948 with its capacity expanded to 48cc. In 1951 a 49cc two-stroke moped was introduced and also a 75cc 2-stroke motor cycle. These were soon joined by other 100 and 125cc two-stroke motor cycles, then later by a 175cc model. All machines were now being developed and tested at Ceccato’s own private track.

At the start of 1953, a 200cc horizontal two-stroke twin with four-speed transmission was introduced, its engine looking almost identical to the Motobi Catria, but which of these came first remains an unanswered question.

The factory site was now expanded to 16,000m² and the number of personnel increased toward its peak of 700.

The Ceccato factory in 1953

Because Pietro was such a large local employer and his personnel management was very social, the town district’s name ‘Alte’ became popularly changed to ‘Alte Ceccato’, which would later be adopted as its official name. Because of Pietro’s passion for racing, the Milan–Taranto and Motogiro d’Italia long distance races were contested in 1953. Two 75cc and two 125cc bikes were entered, and they did complete in positions further down the field, but that was not good for enough for Ceccato and Pietro felt that he needed a winner to promote sales. By a strange chance, fate was about to play a particularly lucky card… A promising but inexperienced engineer called Fabio Taglioni, who had been working for Mondial since 1950, had designed an interesting 75cc overhead camshaft racing engine at Bologna’s Polytechnical Institute. Fabio approached Guisseppe Boselli, head of FB–Mondial with the design, but because Mondial was already successful in 125 and 175cc GP racing, and a 75cc class world title did not exist at this time, Boselli was not interested in it—but introduced Taglioni to Pietro Ceccato in the summer of 1953.

The engine was just what Ceccato needed, so Pietro bought the plans, and with designer Guido Menti started upon its construction. The 75cc prototype, with open valve springs in a temporary frame, was built at a lighting pace and made its first test circuits in the autumn of the same year. The chain-driven overhead camshaft used cam followers with tiny wheels to ride the cam, and initially produced 6bhp at 10,400rpm, but its future looked promising. By November of 1953, Angelo Marelli had already clocked 115km/h over the flying kilometre at the Monza racing circuit. Fabio Taglioni continued at Mondial, but still returned to Ceccato to help with tuning and development of the 75cc motor, before joining Ducati in 1954 as Chief Designer and Technical Director, where he produced a long line of famous Ducati designs until retiring in 1989.

The Ceccato factory in 1957

By 1954 quite a number of Ceccato 75cc racing bikes had already been built and, fitted with an 18mm carburettor, the power output was teased up to 8.5bhp at 11,000rpm. Menti and Pietro replaced the chain-driven camshaft by a train of gears, the aluminium sump received cooling fins, and the open hairpin valve springs were enclosed by a housing around each spring. The frame, and especially the rear swinging arm, was changed to increase its rigidity, and that development would be repeated a few more times yet. In 1954 Vittorio Zito finished seventh in the Milano–Taranto race and Eugenio Fontanilli took first at the Coppa UCMI, Orlando Ghiro finished first in the Moto Giro di Toscane and eleventh in the Moto Giro, while Carlo Carrani finished first in the Trofeo Cadetti. In 1954 Ghiro also broke world records on a partially streamlined 75cc model in both the 75cc and 100cc class on the Castelfusano circuit near Rome. On the one-mile flying start he clocked just under 135km/h, and also set new records for the kilometre flying start and standing start.

In 1955 Ghiro finished fourth in Milano–Taranto and Pozzoni was second at the Giro d’Italia. On the strength of these competition successes, Ceccato added attractive and sporty OHV four-strokes to its road bike range, with cleanly designed 125cc engines. The single down tube cradle frame 6.2bhp Gran Turismo with 16mm carburettor was soon followed by the semi double cradle framed Gran Turismo-S with a 7.5bhp engine and 18mm carburettor. A 150cc GTS model was also created, and the top model for 1954 was a 175cc chain driven OHC bike of which few were ever made. It was also quite straightforward to produce a 100cc derivation from the 75cc racer. This delivered 11bhp at 10,500rpm with a 20mm carburettor and, from this engine a one-off DOHC version was also built, which reached 11,500rpm.

On the first of January 1955, Orlando Ghiro and Vittorio Zito broke 14 world records in both 75cc and 100cc classes.

125cc and 175cc racing bikes were also built. The 125 produced 13bhp at 10,000rpm, and about twenty were made. Ten Ceccato 175cc racers were built at the race department of the FB–Mondial factory and, though their engines produced 14.5bhp, these bikes were not as successful as their smaller counterparts due to fierce competition from Ducati and FB–Mondial in particular.

In the midst of this racing background comes our Ceccato Romeo cyclemotor of 49cc, and dated to 1954.

It’s no competition secret that we can’t tell you anything about details of the motor specification; it’s just that it’s so obscure that we’ve been unable to trace any technical references.

Some elements of the frame pressings look as if they might have been sourced from Casalini, who supplied components to a number of manufacturers around this time. The frame is assembled by electric welded construction with pressed steel girder forks and an Aprilia headlamp.

A lifting handle is included in the crook of frame, which was a common feature for mopeds of the day, for carrying the bike into town houses or upstairs.

A transfer, ‘F. Becar, S. Giorgio DiP’, presumably indicates the original dealer.

Wheels & tyres are 24×1¾ (600×45) making this appear like a small bike with its low-slung motor hanging close to the ground. The engine has an iron cylinder with alloy head, both with horizontal fining, and direct transmission by a steel drive roller.

For drive engagement, the motor pivots from a mounting bracket at the top of the cylinder barrel. There’s a rocking lever behind the bottom bracket. Heel back to disengage, toe forward to pivot onto drive. The rocking lever also has a thimble screw adjuster on the side to adjust and set the roller engagement pressure.

A prop-stand mounts on the left-hand side, bolting a side-stand onto a bracket welded to the left-hand lower frame. It was clearly built with this arrangement, which would seem quite an advanced thought for its date.

There’s an external HT coil behind the saddle stem tube, so the magneto internals must comprise a low-tension coil and lighting generator.

Turn on the petrol tap and fuel feeds into the motor through a Dell’orto TI 10 SA 10mm carburetter with flood button (which we didn’t use, after being advised that the air strangler gave best results): Choke off: Marcia, on: Avvto.

A decompresser trigger is tucked under the left handlebar to help get the motor spinning. Engage drive, pedal off, drop the decompresser when the engine turns over and, while the motor fires up quite readily, it does tend to snatch at low revs.

The rocking lever can latch off the motor; rev to warm up, then pedal off and toe back into engagement. We have to look down to spot the respective heel & toe levers on the rocking pedal because they’re not conveniently positioned like a gear-change would be, and you have to move your foot from the pedal to the required part of the lever to effect the shift. It’s not really a clutch, more a drive engagement device that just works off & on, but doesn’t deliver any actual clutching effect where you could normally feed the operation in.

Opening the throttle, the noisy exhaust sounds like its straight through … and it is!

Power comes in well, and the engine delivers a strong response right from low revs, so much so that if you’re sitting back on the saddle it feels as if the steering goes light, though that’s obviously being assisted by the weight distribution being largely over the back wheel from the short and stubby wheelbase.

Right up its range the engine continues to find surprisingly good torque and climbs hills well, so you may think it’s probably not going to get up to higher revs, but it does pretty well!

The top speed does become limited from phases of four-stroking restricted by exhaust scavenging at high revs, but Ceccato impressively stonks up to a Sat-Nav paced 26mph along the flat, and we manage to urge it on even further to 29mph on the downhill run with the aid of gravity, though the four-stroke misfiring combustion was significantly holding back further motor revs at this speed.

We thought the Ceccato Romeo delivered a strong and gutsy performance for a machine of its time.

We tried the lights; they worked, but were dim, though we’re not sure that it is fitted with the correctly rated bulbs.

At just 51 years old and only a few days after the new year had started, Pietro Ceccato died suddenly of a heart attack on 6th January 1956. The business was taken over by another family company that did not change the course set out by Pietro, and continued all its former activities. Zito won the Milan–Taranto race in the 75cc sports class, and from the 32 bikes that started, only 17 reached the finish, of which 12 were Ceccatos, and scored nine in the top ten as Laverda managed to spoil a clean sweep by sneaking into the fourth position. Orlando Ghiro finished first in the Giro d’Italia after winning all stages. In 1957 Fontanelli finished second at the Giro, which was the last year of long distance racing on public roads, because of fatal accidents in the Mille Miglia car race of that year. The Ceccato company had established some minor exports to Libya, France and Holland, but its greatest sales were achieved in Argentina and, in one period, even more Ceccatos were sold into Argentina than in the Italian home market! Guan Zanella, who started as a motor cycle producer in 1957 at Caseros near Buenos Aires, adopted the 100cc and 125cc Ceccato two-stroke engines for his own frames, the badge on the tank reading ‘Zanella–Ceccato’. Ninety percent of these machines were sold in the Argentine home market and the remainder in surrounding countries with just a few finding their way to the USA, from which the Standard Atlantic Corporation of Miami took up direct imports into the States in 1961.

In 1958, Ceccato started production of a new moped featuring roller transmission, while its frame had a tubular chassis with a telescopic front fork and a swinging arm rear suspension. Sporting victories were also reaped in motocross, grass track and hill climbs. In 1960 a new 24-hour world speed record was established on the French Autodrome de Monthléry by Ceccato’s racing chief Olindo Fongaro and famous French road racing champion George Monneret. Because of a serious drop in motor cycle sales it was decided in 1961 that the production of motorbikes should be ended, to concentrate on other products.

The company remained active in production of motor cycles until 1962, after which the accumulated stock was large enough to last until 1963 when the final bikes were sold. As Ceccato decided to wind up its motor cycle manufacture from 1961, Zanella opted to take on licensed production of the Ceccato engine designs themselves, adopting plant machinery and tooling to resume manufacture in Argentina from 1962, when they also began production of 50cc bikes.

While Ceccato had ceased building motor cycles, the company continued with a change of direction in the products it manufactured, successfully making air compressors and car wash machinery, so the business expanded over the following years. The Ceccato racing team still competed in Formula 2 races and hill climb competition events until the mid-sixties. Pier Carlo Borri took the title at ‘Campionata Montagna’ in 1965 and 1966. Zanella continued producing its Ceccato-licensed engines until 1990, when it started fitting Yamaha engines instead, until the Argentinean dollar crisis forced Zanella to close all activities in 2002.

Pietro’s original plant at Via Bataglia 1 in Alte Ceccato was closed in 2002, as it had become too small. Along the Milan–Venice highway, just outside Vicenza, a new 60,000m² factory was opened. Today Ceccato remains an important player on the global compressed air market. At present the company is one of the largest producers of car and train washing machinery in the world, and has a global network of own offices and importers, while its air compressors have continued to be produced for over sixty years. Because motor cycles were only part of a wider range of products, Ceccato successfully continued, while most of its motor cycling competitors ended up closing their businesses. In memory and honour of the company’s famous motor cycle history, the new factory reception at Via Bataglia holds a permanent display of three brand new motor cycles from the final production year.