Brockhouse Engineering Ltd was established at Crossens, Southport, Lancashire in 1936 as an engineering and sheet metalworking business. In 1937 Brockhouse acquired the entire share capital of Vulcan Motor and Engineering Co, also based at Crossens. Brockhouse sold the rights to the motor vehicle side of the Vulcan business but retained the Vulcan Works for its own general engineering use, and renamed the site Brockhouse Engineering (Southport). During World War 2 the business made aircraft components including fuel tanks and gun turrets.

Elsewhere at the same time but completely unrelated, another piece of our jigsaw was falling into place…

The Welbike was developed at ‘The Frythe’ design and research establishment of the Special Operations Executive at Welwyn in Hertfordshire, under the directorship of Lieutenant-Colonel JRV Dolphin. Other equipment developed at the unit included a special Welgun, and a one-man submarine called the Welsub.

The original concept of the Welbike and its detail was the work of Harry Lester, and it was initially designed to fit into a Mk I parachute drop container 6ft 1in long by approximately 14in diameter. Welbikes were manufactured by the Excelsior Motor Co Ltd in Birmingham, and fitted with a Villiers Junior De Luxe engine.

It seems likely that the Welbike’s first combat drop was with airborne troops at the Battle of Arnhem in 1943, and subsequently on two or three other occasions, but generally the machines saw little active use.

Photographs taken at the 1944 D-Day landings in Normandy show Welbikes being taken ashore, but their main use appears to have been for message carrying around the various camps and airfields.

Excelsior had produced its third and last batch of Mk II Welbikes in 1944 under WD contract 294/23/S1946 and, although there is evidence that a fourth contract for Mk II Welbikes was placed with Excelsior in 1945, this contract was cancelled, and all the completed machines together with those under construction are believed to have been scrapped.

The three completed manufacturing contracts placed with Excelsior indicate 3,853 Mk I and Mk II Welbikes were built and, after the war, most were variously sold off with the majority believed to have been disposed through Gimbels department store in New York. After the war, Welbikes demobbed by the military were seemingly little sold in the UK because they could never legally be used on the public highway since they didn’t have a front brake, just a rear brake, and the law demanded two independent braking systems for road use.

During the war Excelsior had begun to set up its own engine manufacturing facilities under the belief it would be building its own engine for a future Mk III military Welbike. The point at which this process started is not clear, but this must have begun by 1944 at the latest, before cancellation of the final Welbike contract in 1945. Excelsior very probably started design of its horizontal cylinder Spryt motor in conjunction with John Dolphin during the war years, but establishing and equipping the new Excelsior engine shops to production capability in 1946 must have been at least a two-year process.

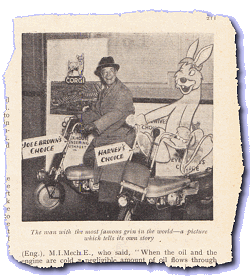

Following the war, John Dolphin founded the Corgi Motorcycle Company with himself as Managing Director, to develop the original Welbike concept into a civilian machine, which he called the Corgi, after its similarity to the tenacious Welsh terrier dog, with its short legs and long body. The Welbike concept subsequently developed into a completely different machine, with practically every aspect of the bike becoming changed for the new Corgi. Considering that Excelsior had built its military predecessor during the war, it might have seemed a logical progression that the company would also make a natural partner for John Dolphin to continue to work with into peacetime, and develop the Corgi prototype onward to production…..

When first announced to the public in developed prototype form in the Motor Cycling’s 21st March 1946 edition, the Corgi’s installed engine had been changed to a new Excelsior made Spryt engine, but the press interview with John Dolphin revealed that ‘The complete machine (including the engine made under licence from the Excelsior Motor Co Ltd) is produced by the Brockhouse Engineering Co Ltd of Southport’.

The Spryt Mk 1 engine began production with an M prefix letter and initial Corgi production got under way by the start of 1947. While a few samples were supplied for military assessments, the majority of early Corgis were mainly allocated to meet priority overseas orders, with exports being secured to Canada and the USA, then later, Belgium, Switzerland, and Denmark.

The original USA importers of Corgis in 1947 are believed to be The Corgi Motorcycle Co Ltd Incorporated of Providence, RI with showrooms in New York.

Like the Welbike before it, the original Mk I Corgi had no means of starting other than push, but this proved easy enough by paddling off with the clutch in, then simply letting go.

In May 1947, Excelsior announced a new model S1 Autobyk autocycle fitted with the very same Spryt motor that was built into the Corgi, and pinned to their clutchcase cover was a brass plate, pressed ‘Excelsior Motor Co, Tyseley, Birmingham, England’. Both machines now shared the same M serial engine prefix and continued the ongoing number series, so they were only being made in one place, and that was at Excelsior.

The Corgi wheels were still spoked at this stage, with a curved rigid-fork like the Welbike, but it was shortly found that the spoked wheels were failing under the harder strain of road surfaces from the constant pounding by a rigid fork, and higher mileages involved with more regular use.

After the war, Brockhouse had acquired the Sunbeam and Karrier trolleybus businesses from Rootes and, in 1947, purchased the British Motor Boat Manufacturing Co to take over its business in making small cars, tractors and engines.

During 1947, Ralph Rogers (company president of Rogers Group, the new owners of the Indian Motorcycle brand) came to Britain to try and secure import rights for British motor cycles to the USA and, on his visit, met with John Brockhouse of Brockhouse Engineering. Brockhouse agreed to invest in Indian in return for a secure export base for Brockhouse products—though the timing of this meeting in 1947 meant the Corgi was already being built and exported through other channels before the Indian connection had been established.

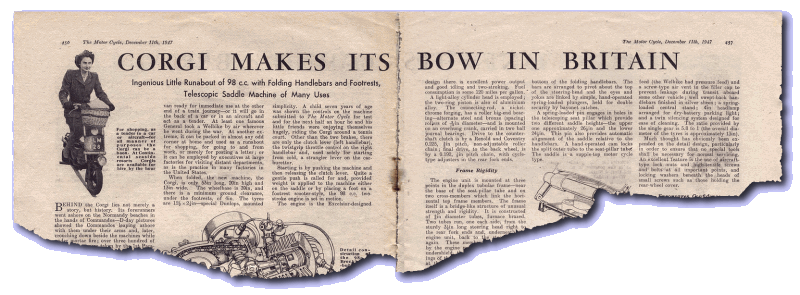

In an article ‘Corgi makes a bow in Britain’ in The Motor Cycle on 11th December 1947, it was announced that the Corgi would finally become available on the British market, but it would be well into 1948 before Brockhouse Engineering actually delivered bikes for sale to high street shops. All the early Mk 1 Series-1 Corgis (1946–47), were almost entirely built for export, with engine numbers up to 2000+, curved front forks, and spoked wheels, and it’s reasonably possible that these early export machines were built up using some left-over Welbike components from the fourth (cancelled) contract.

The Mk I Series-2 Corgis had already introduced a straight fork set in 1947 to replace the earlier curved fork, and an option of disc wheels was announced in January 1948.

While many publications reflect that Brockhouse adopted the Corgi project and built the bike complete with the licence-built Spryt Mk 1 engine, that clearly wasn’t the case at this time, because Excelsior looked to be using more of the same Spryt engines in its autocycles than Brockhouse was building Corgis!

Corgi serials had reached frame number 2372 and engine number M5385 before the first Mk I Series-2 bike was recorded for home market sale in 1948, which becomes a particularly important year for a sequence of significant changes.

At some point, John Dolphin had either sold Brockhouse a license to the Corgi’s manufacture, or completely sold out his Corgi Motorcycle Company to Brockhouse (which is the more likely scenario, since Brockhouse had proven more inclined to buying into its business interests).

As Corgis finally went on sale in British high street shops in 1948, its manufacturer was indicated as Brockhouse by transfers on the top of the fuel tank, imprinted pads on the tank sides, and a ‘Brockhouse Engineering Southport’ brass plate pinned to the face of the chaincase cover plate, but there are several good reasons to suggest that Brockhouse still wasn’t actually building the Spryt engine at this time, and that it was actually adopted in a later transition from Excelsior.

It’s very hard to see how Brockhouse would have been in any position to manufacture the engine from the start of Corgi production in 1947—after all, it had taken Excelsior some two years to establish their own engine shops, so Brockhouse surely couldn’t have achieved the same feat within less than half that time?

Excelsior continued building its S1 Autocycle model into 1948, and still continued fitting the Mk 1 Spryt engine with ongoing serials with an M prefix, rather indicating that the motors were still being built by Excelsior up to a point sometime later during 1948.

In 1948 the home market Corgis were initially offered with a choice of spoked or disc wheels for the first two months (to use up stocks of the spoked wheels), before the disc wheels became the standard fitment; then Brockhouse offered trade-in allowances to encourage owners to replace their spoked wheels with the new disc type, while others were exchanged under warranty when the weaker spoked wheels failed. Consequently, very few early machines managed to retain their original spoked wheels.

During the year, Brockhouse sold its trolleybus business on to Guy Motors.

Corgi Spryt S1 engines switched from M-prefix to a W-prefix later in 1948 somewhere around the 6300 mark, but still continued the ongoing number series, which probably identifies the point at which Brockhouse took over building the Spryt Mk I engine under license for the Corgi. It’s likely this transition represents the changeover point at which all the casting patterns and machining fixtures were transferred from Excelsior to Brockhouse. Up to this point Brockhouse would have been purchasing the Spryt Mk I engines from Excelsior; from then, only subsequent W-prefix motors would have been Brockhouse manufactured under licence from Excelsior.

Corgi frame numbers had reached around 3500 by the end of the M-prefix motor during 1948, which suggests that Excelsior might have built up to around 2,800 of its S1 autocycles with the Spryt Mk I motor over the same period.

At this point Excelsior would have been finished with the Spryt Mk I engine, and many of the patterns and fixtures for the forthcoming ‘inclined’ Spryt Mk II motor would already exist since it shared many aspects with the established Goblin G2 engine.

A picture of the S1 autocycle in The Motor Cycle for 7 October 1948 shows the engine with an inclined cylinder, so it looks as if Excelsior had changed over to the Spryt Mk II engine at about the same time. Excelsior’s Mk II Spryt engines are characterised by an S prefix to the engine serial and a restarted number series, while the frame numbers change from the original SA series to SB, indicating the switch to mounting of the new inclined engine.

There doesn’t seem to be any official record of when the W-prefix engine serial ran out, but it was somewhere into the early 10,200+ number group.

The first Mk II Corgi was recorded in April 1948, at frame serial 6303, and with a new engine number series starting from 16005, but this was presumably a development prototype, since it didn’t actually become available for sale until July 1948.

The main feature of this new model was the addition of a kick-starting facility to the Spryt engine. The installation incorporated a dog clutch on the output transmission, to disconnect the drive shaft from the final drive sprocket. This was controlled by the right hand footrest, folded up to disconnect the drive, then folded down to engage. Brockhouse also offered a conversion kit for anyone wishing to convert an earlier Mk I Corgi to kick-start operation, so any M or W prefix engine in a bike with a kick starter … may not be quite what it seems.

And guess what? Our kick-start ‘Mk II’ Corgi shows engine number Mk I W9890, so it’s actually one of these post-fit conversion kit Mk Is!

Waving a tape around the bike to get some impression of its diminutive dimensions, measures 54 inches end to end (just 4ft 6in, that’s small), and the handlebars fold down to compact at 20 inches high × 11 inches wide.

The footrests are only 5 inches above ground level, so could presumably be quite easy to ground on corners, but they do fold up, though we’re not sure that’d much consolation by the time they might have dug in and be spinning you round in the road.

By means of a locking lever and engagement pin on the saddle stem, the seat height can be extended to a maximum of 27 inches, pushed down to a minimum height of 20 inches, or removed completely.

The handlebar height in up position is 38 inches, and they pivot upward by swivelling a tube in the bronze top yoke, then engage into position by locking pins to the bottom yoke.

Bars fold down by unlatching two locking pins that engage the bottom of the handlebar stems into the bottom yoke, then a large diameter cross-tube turns the bar assembly down within the bronze top yoke.

The rigid front forks are simply short and straight tubes, and the top of the steering head is only 17 inches above ground level.

The rigid rear body section is panelled in to form a mudguard and give cleanliness from the drive chain. A handle bolts across the back of the bike from bosses on the rear frame, allowing a lifting point—though it doesn’t make Corgi any lighter when you want to pick it up. At an all-up weight of 7st 4lb it’s a pretty hefty piece of metal and, even if you’re lifting one end, at a time it’s still 3st 10lb front & 3st 8lb rear.

Disc wheels & tyres are sized 12½ × 2¼ which converts back to an 8-inch rim size, and 2.50 width mobility tyres are available that will fit, and in a suitably adequate 4-ply construction.

The engine is an Excelsior Spryt Mk I, with a Wipac FW-1054Z Geni-mag mounted on the left-hand side.

A silencer cylinder is mounted across and between the frame rails below the seat, and its steel central tube is closed at the ends with cast aluminium caps, which seem practically impossible to seal on their joints to the can or the exhaust tubes, so smoke will generally find its way out of most parts of the system.

Despite the leaks, our Corgi’s bark sounds beautifully mellow and smooth—that exhaust tone is absolutely gorgeous!

Starting should be straightforward, but this breed of dog is known for being temperamental…

The shallow fuel tank is formed of aluminium, with a balancer pipe between the two halves, and a pull-on Ewarts fuel tap plunger under the left rear of the tank.

The Amal 259, 7/16-inch bore carburettor has a tickler to flood the float chamber, and a lever choke, but we’re not sure what combination might be best for the conditions, so there’s going to be some guesswork involved.

The dinky kick-start arm is only 4 inches long, which is the same length as the folding arm on its head, and kick-start operation is notorious as a cartilage buster in your knee joint. After a few kick-starting attempts without choke, with choke, throttle closed, throttle open, flooded without choke, flooded with choke, the knee is starting to ache, so we give up on that. It’s great if the bike starts on the kick-start like it’s supposed to, but it doesn’t—so we decide to give it a push, and it starts straight away on choke.

Apparently this failing-to-kick-start was not an uncommon complaint, and many riders found it easier to paddle-start their Mk II bikes in the same manner as the Mk I.

The problem now is that you need to use your left hand to reach under the tank fairly quickly to turn off the choke, so the motor can run clear before it coughs out. The trouble is you’re now holding the clutch in with your left hand, so first you’ve got to fold up the right-hand footrest! This may sound completely mad, but the Mk II Corgi has an odd feature—there’s a dog-drive engagement mechanism connected across the motor to the right-hand footrest. When the footrest is folded up it disconnects the main drive so the motor can be kick-started. When the motor is running, you then pull in the clutch and fold down the footrest to effectively put it into gear, then you then ride the bike much like any other single-speed autocycle, but without a latch on the clutch.

You need to think of the right-hand footrest as a gear lever: when down it’s in drive, and when up it’s in neutral.

Generally if you’ve started on choke, then it’s easier to stop the motor and restart again once you’ve grubbed under the tank to find the shutter and latched it off.

Unlike an autocycle, Corgi has no pedals to assist its take-off, so the motor and clutch have to do all the work. Little problem here since Excelsior’s engine seems to deliver very adequate torque, and progressively sliding home the clutch lever results in a smooth getaway as we balance the power with the throttle twistgrip.

This carefully measured launch is accompanied by a constant and mellow exhaust tone as the motor pulls under load—it sure does sound good.

Opening up the throttle produces the feeling of a strong response from the motor, so there seems to be plenty of power for the unusual handling characteristics of this small and unfamiliar machine. The lack of suspension can make the handling feel a little unpredictable on occasions, but the technique is to keep the steering pointed in the direction you want to go, then hope the bike will follow the course.

The rear footbrake could be very effective if you wanted to plant your left foot on it, so most of the time required a measured application. The front brake also demonstrated a capable stopping force, so both brakes were clearly benefiting from the mechanics of the small wheel size.

The low footrests can present a very clear danger of grounding on turns, with the ever present possibility they might dig-in despite their folding pivots, so we err on the side of caution here and don’t push our luck too much on cornering.

Indian Papoose

With no speedometer fitted, we resort to our pace vehicle yet again, and the hill climb section is dispatched with relative ease as Corgi powers up at no less than 23mph as it crests the rise. The following on-flat run only managed to scrape 26mph, as the engine broke into an inexplicable fit of misfiring that cleared up again as soon as the speed dropped down a little. We stopped to clean the plug, but the same thing happened, so we returned to base to check the points, ignition set, and change to a new plug, but exactly the same thing happened again.

We tried a downhill run, but couldn’t get through the inexplicable misfiring, so the best we could clock with the assistance of gravity was 29mph—thwarted!

Some reports claim Excelsior had tested the Spryt engine to a maximum speed of 47mph in an autocycle frame (we tested a special blueprint-tuned G2 to a paced 48mph downhill in the 2×2 article back in October 2014), but this would certainly have been referring to a two-speed Goblin G2 model with some 25% ratio increase against the single-speed Spryt. Mathematically this suggests that speeds up to 35mph could be likely from the Spryt motors, however there was some concern about the motor over-revving at such speed, so it was recommended that ‘The Corgi should not be run at speeds exceeding 30mph, except for very short distances’.

Brockhouse was also developing some of its other activities, and now listing its British Motor Boat Products Division from the Southport site, with advertising for the HoeMate tractor in 1949, then further PlowMate and CultMate three-wheel tractors in 1950, when it also introduced the four-wheel President tractor as the new largest machine in its range. Brockhouse also established an export channel to the USA for its motor cycle products…

Despite losing the prime initiative for civilian motor cycle sales to Harley–Davidson, Indian retained a very significant motor cycle market share up to and throughout the Second World War, when control of the company passed from Du Pont, who had acquired the business in 1930, to Rogers Group in 1945, which began the start of a steady decline towards the end of production and the bankruptcy of Indian in 1953.

Brockhouse had acquired some share interest in the Indian Company during the early post-war years and, having established engine shops at Southport to produce the Corgi cycle chassis and later adopt its Mk I Spryt engine licensed from Excelsior in 1948, used the same facilities to build and present the Indian Brave 250cc single cylinder side-valve motor cycle in 1950. The Indian Brave was initially built purely for export to the USA and distribution through the Indian dealership network, so didn’t generally become available in the UK until after the collapse of the Indian company in 1953, when Brockhouse Engineering acquired full rights to use of the Indian brand name.

An Indian Brave and a Corgi

in the Brockhouse display

at the 1952 British

Industries Fair

Having established its trading relationship with the Indian Company in the early post-war years, later Mk II & Mk 1V Corgis also were sold into the US from 1950 as the Papoose model under Indian branding.

The Brockhouse 250cc side-valve engine unit was also sold to Dot and OEC for use in some of their motor cycle models, but the Indian Brave found little favour in either the US or UK markets and was discontinued in 1955.

A number of Indian Papoose machines, however, were employed by the US Air Force during the Korean War for use by maintenance personnel, and were often kept aboard aircraft for use in moving around the bases.

A two-speed Corgi with an Albion J2 gearbox was produced, initially as only 350 Mk III models built during 1951. A redesign produced a revised two-speeder in the form of a new Mk IV model with telescopic forks and a windshield set. This was presented at the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1951, for market sales to begin in 1952.

When the Corgi mini-bike was introduced with its compact design, tiny wheels and historic military origin, it was a fashionable novelty that appealed in the immediate post-war years. The trouble with fashionable things is that they tend to go out of fashion, and sales of the Corgi started falling away in the early 1950s as a new fad for scooters started to capture the customer’s eye.

The Mk I model recorded frame numbers up to serial 6,302 before the announcement of the first Mk II in April 1948, which represented some further 18,700 machines up to October 1952. The two-speed Mk IV model was introduced in November 1951, and only accounted some 2,000 examples over the Corgi’s three final years, clearly demonstrating how the market had moved on by the time the last Corgi rolled off the assembly line in October 1954, completing the series at frame number 27050.

In 1955, Brockhouse claimed the Southport factory had not been profitable since World War 2 and used this as justification to end all motor cycle production and begin winding the site down. After the Indian Brave motor cycle ceased production in 1955, the BMB Division four-wheel President Tractor became the last remaining vehicle to be manufactured from the Southport site when it finally closed down in 1956.

A new Brockhouse machine shop was established at West Bromwich to manufacture hydraulic transmissions, under the name of Brockhouse Engineering, while an arrangement was made with Enfield Cycle Co to manufacture practically the full range of Royal Enfield motor cycle models from the 150cc Ensign two-stroke single to the 700cc Constellation four-stroke twin under Indian branding, so Brockhouse could continue selling various Indian models for the US export market. Occasional AMC Matchless motor cycles were also factored with Indian badging, and in 1960 Brockhouse completely divested its involvement with motor cycles by selling the Indian branding rights to Associated Motor Cycles.

By 1961 Brockhouse (West Bromwich) was going full steam ahead, with 220 employees working on automatic hydraulic transmission systems incorporating hydraulic torque converters for use in various industrial appliances.

In 1964 the factory was extended, and the Brockhouse Group of companies still continues in business today (2017)—which goes to underline that its better future was definitely not in motor cycles.