Picking up our chapter in the late 1930s, early Excelsior Autobyks (autocycles) first appeared in November 1937, with a rigid frame and fork, and a short half-tank for fuel that incorporated a separate oil reservoir. No engine covers were fitted but there was a round toolbox between the seat tube and seat stays, while inverted handlebar levers controlled both brakes. A back-pedalling mechanism for the rear brake was introduced later. The price of an Autobyk in 1939 was 18 guineas (£18-18s).

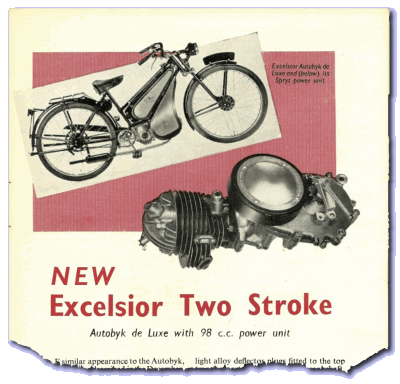

In 1940, a second model Autobyk De Luxe was introduced, with a larger, flat-sided fuel tank, engine covers, and a telescopic fork.

Excelsior motor cycles were produced until 1940, when the company was turned over to war-related work, which included manufacture of the Military Welbike, installed with the Villiers Junior De Luxe engine. During the war years, Excelsior began to establish its own engine manufacturing shops, intended to produce further motors for the Military Welbike. Though the facilities weren’t completed before the war ended, they would be ready and available to start manufacturing engines for post-war civilian production in 1946.

After the war, Excelsior returned to civilian sales in 1946 by re-listing their pre-war Autobyk with the Villiers Junior De Luxe engine. As production of the Autobyk resumed, it now included engine covers and a pressed-steel spring fork as standard, and was finished in black with cream panels on the tank sides and the engine covers. The price in March 1946 was posted as £35-15s + £9-13s-1d purchase tax but, because of the difficulties in obtaining raw materials in the immediate post-war period, and rampant inflation, this price could not be held and would be increased to £39-10s + £10-13s-4d purchase tax on 17th June.

Now we enter the strange imaginarium world of Excelsior’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, to find an evil mix between a Sprite and a Nymph. Sprytes are almost always female in appearance, have wings and can fly, are naughty, mischievous, flirty, and can easily be provoked to bite—so why might you call an engine after one of these fairy spirits? As it was, Excelsior seemed as if they had developed a sudden inability to spell properly when it came to naming their autocycles and engines: Autobyk? Spryt? What’s a Spryt?

The earliest presentation of one of the new Excelsior Spryt engines appeared in the Motor Cycling edition of 21st March 1946, revealed in an announcement of the new Corgi. The Spryt engine featured a horizontal cylinder and was arranged with a left-hand side magneto flywheel, in a very similar layout to the Villiers Junior De Luxe engine that had been fitted into the military Welbike.

It wasn’t until August 1946 when the new models for 1947 were being announced, that Excelsior re-coded its single-speed Villiers Junior De Luxe Autobyk as 47/V1, and presented its latest two-speed Super Autobyk. Powered by Excelsiors own 98cc Goblin engine, this became the only British-made two-gear autocycle, and was initially coded 47/S2, but was soon re-designated 47/G2 in November. The price of the Super Autobyk was initially set at £48-10s + £13-1s-11d purchase tax.

A new spring fork was introduced with the 1947 models; this had its fork blades each made of a single Reynolds 531 tube and used four rubber bands to provide the suspension. Again, raw materials prices and inflation were reflected by the increasing cost of these autocycles, when in March 1947, they went up to £45 for the 47/V1 and £55 for the 47/G2 (and also with purchase tax as extra on both these prices).

The G2 Autobyk only became available for sale from May 1947, and by the end of the same month, another autocycle had been announced to join the Excelsior line-up!

The Spryt engine was the motor originally designed and built for the Corgi, but Excelsior seemed to have suddenly decided to employ the Spryt in its latest S1 model Autobyk. The autocycle engine shared the same M-serial prefix with the Corgi and continued the ongoing number series, which strongly suggests that Excelsior was making the Spryt motor at this time for use in both machines. All early Corgi Mk I production was allocated for export, and the Corgi didn’t even become available for sale on the British market until 1948.

There didn’t seem to be much reason at this time for Excelsior to be introducing its own Spryt-engined S1 single-speed autocycle when it was already selling the Villiers-engined V1 model, and obviously had ample stocks or contract commitments to the Junior De Luxe motor. Maybe Excelsior decided it would rather be selling its own S1 Spryt engined single-speed autocycle in preference to the V1 Villiers Junior De Luxe, because presumably the profit margin should have been higher for their own-make motor.

The original S1 frame fitted with the horizontal-cylinder Spryt Mk I engine became identified with an SA serial prefix, and our first objective was to source one of these early type S1s for examination and road test. This would never be an easy task, because there don’t seem to be so many of the Mk Is about, but we were lucky enough to fall upon one that appeared to be a late registration example on 26th January 1949, with engine serial Mk IV.M4978 and chassis SA/8232.

Features of the frame include the band-suspension forks, a pressed steel rear carrier, and back-pedal rear brake with proper shoes operated from the freewheel by a Bendix in the hub (a lot better than the pathetic ‘Coaster’ type hubs with the expanding-cone brake).

The engine is fitted with the Miller FWXB magneto flywheel set, which gives a miserable 9W output from the lighting generator, so weak that it might barely seem worth the trouble of even switching the lights on the small Miller headlamp at night, there’d be little expectation of being able to see anything!

Pinned to the clutch case cover there’s a brass plate, and pressed ‘Excelsior Motor Co, Tyseley, Birmingham, England’, so little question who made this Spryt engine in 1948, at a time when it was generally believed that Brockhouse were building the Corgi and making its engine under licence—no they weren’t!

There are some aspects of the horizontal cylinder arrangement on the Spryt Mk I that don’t look so ideal for its installation in an autocycle, for instance the decompresser cable constantly had ‘issues’ in fouling the front mudguard when the steering turned, and so annoying to this owner that the decompresser was removed and replaced by a blanking plug! Also the badly positioned Amal 259/01 carburettor sits quite forward on its manifold, and so reportedly prone to being sprayed with water and grit from the front wheel, that a shield was improvised by some previous owner and bolted onto the left-hand leg shield stay from the cylinder head. The petrol tap switches push-on/push-off at the bottom left of the fuel tank, then tickle the carb flood button and engage the choke by a rod that rises through a port in the left-hand leg shield.

Pedal starting without the decompresser isn’t as difficult as we expected, a few spins of the pedals and the motor reluctantly rattles and rumbles to life—well what do you expect for a 68-year old autocycle?

While the pace vehicle is readying, we roll off the rear stand and clip it into the latch at the back of the rear mudguard, then hook a bungee strap on too for extra security. These old autocycle rear stands will quite commonly unlatch over a bump, then you’re dragging them behind you down the road … and this stand certainly looks as if it’s unlatched a few times in its life!

Pedalling away up the road we unlatch the clutch lever and open the lever throttle to feed in the power—maybe less like power and more like some reluctant old agricultural device slowly gathering impetus, but that’s quite enough for an initial impression of the handling. The band-fork Excelsior autocycles have a long 52-inch wheelbase, and are some 80 inches long, so they always prove pretty cumbersome at low speed. The situation isn’t made any easier by the traditional pull-back North Road handlebar pattern, which doesn’t afford the best control of the steering, and generally results in a bit of a wobbly take-off.

Usually longer wheelbase bikes become more stable at speed, but this S1 Spryt doesn’t really do speed … it’s a lot better at slow! Picking up a few mph presents the appreciation that it’s partial to a bit of wobble and weave from its ‘wavering wheels’, so initial impressions are a little disconcerting—and everything just gets worse the faster you try to go.

There’s a modern digital cyclometer mounted on the bars and, as the speed creeps toward an indicated 25, you really begin to wonder if you should have made out your will before undertaking this experience. The best interpretation of ‘slow & safe’ on this bike is found under 25mph, but the motor will rumble on past that marker through intermittent bouts of 4-stroking combustion, to generally lumber along at around 28 on the flat, at which its getting well into the unhappy zone of shaking and vibration.

Nobody is going to hold this bike for long at that speed, because it’s a bit like hanging on to a runaway train, but it’s our duty to do the maximum downhill run—or die trying, which at this moment does seem very possible! Our first run scraped up to 32mph on the cyclometer before the nerve failed and we bottled out, then gathering all our determination and resolution for the second run, saw 33 on the cyclometer, which our pacer actually confirmed at a 34mph reading on the satnav!

The following uphill climb slowed to 16/18mph, with a long snake of impatient traffic having built up behind, but the Excelsior still slogged up without any need for pedal assistance.

The handling is best described as clumsy and cumbersome, while both brakes are crude to control, though reasonably effective in operation.

Returning to base, the bike’s owner was fully in agreement that the handling was little short of terrifying, and seemed most incredulous that we’d actually managed to exceed the 30mph barrier—and survived!

The Excelsior Spryt Mk I horizontal engine ran up to about serial 6300 with the M prefix, but it’s not so easy to figure out how many of the S1 autocycles were built with the Mk I engine since the Corgi also used the same motor. Corgi had reached around frame 3500 by the end of the M prefix motor, which suggests that Excelsior might have built up to around 2,800 S1 autocycles with the Spryt Mk I motor from May 1947 and into the season of 1948—where everything was about to change.

While Villiers formally announced its new F-series engine models late in 1948, in preparation for the 1949 season, it’s very likely that customers of the Junior De Luxe autocycle engine were informed earlier in the year that the JDL would soon be replaced with the new 2F motor. Indeed, several manufacturers already turned up with new 2F-engined autocycles at the November 1948 Earls Court Motor Cycle Show, so they must have known this somewhat earlier to have their new models ready for display.

Mk I Corgi Spryt engines switched to a W prefix in 1948 somewhere around the 6300 mark, which probably identifies the point at which Brockhouse took over building the motor under license for the Corgi, and a picture of the S1 autocycle in The Motor Cycle for 7 October 1948 shows the angled cylinder, so it looks as if Excelsior changed over to the Spryt Mk II engine at about the same time.

Excelsiors Mk 2 Spryt engines are characterised by an S prefix to the serial and a restarted number series, while the frame numbers change from the SA series to SB, indicating the switch to mounting of the new inclined engine.

The S1 Spryt B (indicated as Mk II cast onto the crankcase) was basically a cheaper single-speed version of the Goblin motor. The geared G2 offered an appreciably higher overall top ratio, raised to 8.5, from just 11.3 on the single-speed Spryt, representing a mathematical 25% increase, and better speed potential (which is what Excelsior would have been quoting in summer of 1946 as achieving test speeds up to 47mph. We actually pace-tested a blueprint-tuned G2 up to 48mph on a downhill run in the 2×2 article of October 2014). On a good G2 under ideal downhill conditions around 45mph could be possible—but on a single-gear Spryt, there’s no chance of a speed anywhere near that.

Prices posted at the 1948 Earls Court Motor Cycle Show found the cheapest autocycle being the Aberdale JDL: £39-14s-9d + £10-14s-7d purchase tax. The New Hudson JDL was £44-0s-0d + £11-6s-10d purchase tax, the James JDL also £44-0s-0d + PT, and the new James 2F engined Superlux £47-10s-0d + £13-3s-1d PT. Excelsior’s V1 & new S1 Spryt Mk 2 autocycles were posted at exactly the same price, £45-0s-0d + £12-3s-0d PT, while the Excelsior G2 was by far the most expensive autocycle listed at the show: £55-0s-0d + £14-17s-0d PT.

Excelsior only posted discontinuance of its Villiers engined V1 autocycle at the end of the 1949 season, most probably when stock of its Junior De Luxe engines had finally been exhausted, by which time the new inclined-cylinder S1 Spryt Mk 2 autocycle had already taken its place, so now we’re set to try one…

Frame number SB3968 with engine number S4888 is dated at 1952, and the obvious changes to the cycle frame include adoption of the round/conical fuel tank that was also used on the G2. It’s a great character tank that brings a smile to your face, and looks rather like one of those old style fire extinguishers.

The headlamp has changed to a much larger 6-inch diameter Wipac unit, which is now powered by the Wipac 6-pole Genimag with 21W lighting output. The magneto set is now mounted on the right-hand side of the motor, the cylinder is inclined, and the crankcase is cast with Spryt Mk II, so this engine is a completely different bottom-end casting to the earlier Spryt-1, but shares the same barrel, head, piston, and many other internal components with the earlier motor.

The same Amal 359/01 carburettor is now set backwards facing on a different inlet manifold, so it’s no longer in the direct firing line for grit and spray off the front mudguard, so that’s a big improvement.

The fuel tap push-on/push- off is still located in the same left-hand position on the conical tank, so we turn on, tickle the flood button till we see a presence of petrol, and flip over the choke strangler to richen the mixture.

This time we have the luxury of a decompresser to help us get the pedals into a starting position, because the inclined cylinder resolves all issues with the decompresser cable fouling the front mudguard. The decompresser really does help this bike because this Spryt Mk 2 motor seems to have more compression than our previous Mk I—maybe it’s not so tired?

The decompresser helps because you can’t turn back the pedals into a starting position because of the back-pedal brake, and trying to turn the pedals against the compression would be slow and irritating.

Theoretically you could start one of these by standing off the bike and kicking down on the pedals while holding on the decompresser to get the motor spinning, then follow through the stroke as you drop the decompresser—but this bike doesn’t want to play that game, so we have to pedal it up on the stand while fiddling with the throttle control lever to get it to cough into life … then it stops again.

After a couple more efforts flooded with the strangler, then not flooded with the strangler, the motor finally decides to catch, and we run it a while to clear the choke.

Latching in the clutch lever we note the rear wheel is still spinning, so before nudging it off the stand to some potential disaster, we back-pedal the brake—but the engine stalls! OK, it’s got a badly dragging clutch, so we’ll probably have to pedal it away up the road, and treat it like a direct-drive machine … maybe the clutch might free up when it gets going and warms up a bit?

Off we go, and there certainly feels like more torque from this engine, less mechanical noise (though it doesn’t have the leg shields fitted), and doesn’t weave and wander quite so much as the first S1, possibly because its wheels are re-laced with heavier gauge spokes, and has new rims that run true, and tyres that are properly seated—these things can make a difference!

Pulling in the clutch lever on the approach to our first junction, the clutch is still dragging, so we hold it back a little on the brakes and throttle up slightly to make sure the engine doesn’t stall, then pace the junction so we don’t have to actually stop. It’s clear this clutch is going to be a bit of a nuisance. Usually the clutches slip when they go; it’s quite unusual to find one that drags like this.

The North Road handlebar pattern on this bike seems less of a pull-back form than the previous bike, so you can apply some better control to the steering, which does make the ride a little less ‘concerning’, but the steering is still clumsy and cumbersome. The handlebar shape is still not really suited to adopt a crouched position, but that doesn’t appear necessary anyway since the motor capably manages to pull up to revs.

On flat was paced at 33mph upright stance and 35mph on the downhill run. There didn’t seem so much four-stroking from this engine, but it did suffer several bouts of misfiring instead, so either some malady in the magneto set or a whiskering plug issue was going on there. Our Spryt 2 motor slogged uphill to crest the rise at no less than 20mph, so managed a slightly better account of itself than our Spryt 1.

The clutch never improved during our run, so there was probably something not right about that, and wasn’t helped by the latch lever having lost its spring, so you had to flick the latch up with your finger to get it to hold-off every time.

The lights … actually worked! We were most surprised! The 18/18W dipper headlamp managed to produce a sort of reasonable illumination, and the 3W back light was glowing nicely too!

Is this the first autocycle we’ve run that had decent lights?

Both brakes worked reasonably considering they’re 65 years out of date.

The ride felt hard from the rigid rear, but the front forks seemed quite reactive, and felt as if they smoothed out the front-end better than a spring fork might have done.

Only Excelsior and Francis–Barnett autocycles employed band fork suspension and, last time we tested a Powerbike-56 back in August 2004, we were most impressed with the ride on that machine, so band forks—OK!

By the mid 1950s, autocycles were becoming a fast dying breed in the face of the rise of the moped, motor scooter, and automobile.

Excelsior’s S1 & G2 autocycles were both posted as discontinued at the end of the 1956 season.