The once great British motor cycle industry has almost completely collapsed. There isn’t really anything much left now, just a few ruinous fragments of the old names sliding into the abyss… At this time it’s hard to see any of the traditional brands making a comeback—just all too late now… This felt like a terrible time for British motor cycle enthusiasts, lamenting the tragic loss of a national, world-leading industry. The motor cycling press would clutch at every straw floating by on the torrent of despair, as if hoping on hope that there might still be some chance of salvation. The year is 1980: the start of a fresh decade, and a new age.

Perhaps some prospects for British motor cycling may not be in trying to recover the old, but starting anew?

Our first traceable reference to this feature appeared as a small column piece in the ‘Ride On’ section of Bike magazine No.89 August 1980, and it related that this project started with a comparative costing exercise to build a new 50cc machine wholly manufactured and assembled using only UK sources: £660, against the same complete bike in Taiwan: £130!

Unsurprisingly, the home option was considered too expensive, they’d never be able to sell anything at that cost, but the Taiwanese option was considered too ludicrously cheap, and there were associated concerns about quality and warranty. A compromise was decided: to use as many British parts as possible to finish a machine generally based on Italian components, and a further hope to progressively replace the foreign components with British parts sourced at comparative prices.

Kestrel Motorcycles was established by Managing Director Richard Newton, with its head office at 132 High Street, Southampton which, given the hometown’s historical maritime association, and some members of the business coming from a powerboat racing background, makes it unlikely for glass fibre work not to feature significantly in the design.

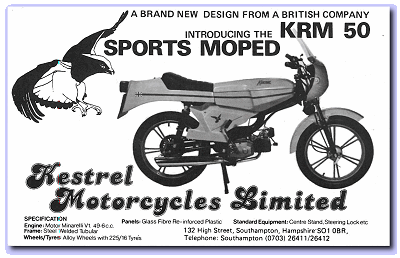

An initial picture appeared with the first press release in August 1980, describing the bike as powered by a Moto Minarelli 49.6cc single-speed automatic engine, aimed at sales in the sixteener sports moped market, and quoting an initial price of £303.47p + VAT (£349).

A notification had been circulated to the trade, and 63 dealers across the country had reportedly already expressed interest in selling the machines so, despite the lack of any particular detail at this stage, there seemed a fairly convincing belief that the new ‘Kestrel’ might actually happen.

Studying the small accompanying black & white picture to glean whatever one may, the cycle chassis appears to comprise a formed tubular spine frame with swing-arm rear suspension and telescopic forks, extensively clad with sports-styled glass fibre moulded body fittings, a single saddle, cast alloy wheels, and semi-faired headlamp. The bike was presented as new, but its background seems to go a little further back than the press release suggested…

Just flashback for a moment to 1977, and the closing phase of AJW Motorcycles. The original AJW company was established at Exeter by Arthur John Wheaton in 1926, and built its first production model with a 996cc British Vulpine V-twin engine.

The firm changed hands in 1945 when the founder sold out to Jack Ball, who firstly relocated to Bournemouth, Hampshire, then on to Wimborne in Dorset. Production using JAP engine models returned in 1948 on a fairly limited scale, with a Speed Fox speedway bike, and road-going Grey Fox side-valve twin that was dropped in 1950. A 125cc JAP-engined Fox Cub two-stroke was briefly listed for 1953, and further offered a built-to-order 500cc JAP single, but both concluded as their engines were discontinued later in the same year. The speedway model remained in production up to 1957, when Villiers bought out JAP and closed down its remaining engine manufacturing. The Birmingham-built Hercules Her-Cu-Motor moped similarly became a casualty of the Villiers/JAP conclusion, due to loss of its unique 50cc JAP engine.

To continue the business, AJW switched from trying to manufacture machines itself, to factored importation of Italian built Giulietta 50cc Minarelli-engined light motor cycles and mopeds, up to 1964 when the business seemed to go into mothballs for a decade, before resuming in 1974 with a new range of AJW-branded imported Italian Minarelli-engined mopeds and light motor cycles up to 125cc.

Period literature lists this business as AJW Motorcycles Ltd, Crowvale Depot, 8 Stone Close, Horton Road, West Drayton, Middlesex.

The entire imported range was de-listed in November 1976, whereupon J O Ball Ltd appeared to have sold on the AJW name to Chinwood Ltd, 80a Weyhill Road, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 3NP, which seems like a very small operation, since this address is now no more than a fruit and veg shop! In August 1977, Chinwood presented a new AJW Fox Cub 50cc automatic Minarelli-powered machine offered in two versions, as a moped with pedals, or as a kick-start motor cycle. Destined to become the very last AJW model before discontinuance in February 1979, this machine was only manufactured in very limited numbers.

While these Fox Cub models were built upon 2.25 × 17 spoked wheels, and seemed to have a sheet steel fabricated frame, might there appear to be more than a few coincidental similarities to the Kestrel design with its fibreglass body mouldings, and use of the same fan-cooled Minarelli V1 automatic engine?

One way or another, Kestrel would appear to have ‘inherited’ the design and tooling of this final Fox Cub model after AJW Chinwood ceased trading. It seems apparent that their ‘machine wholly manufactured and assembled using only UK sources costing £660’ was based upon an updated costing of Chinwood’s last AJW Fox Cub, and this original design was probably also what was comparatively quoted for the cheaper Taiwanese costing.

Kestrel settled, however, on an Anglo-Italian combination for their machine, going to LEM at Lippo di Calderara di Reno near Bologna for most of the rolling chassis components. LEM was a relatively new company, only established in 1973 to manufacture mopeds, scooters, and children’s mini-cross bikes. LEM replaced the fabricated sheet frame with a tubular form frame, and updated the spoked wheels to cast alloy.

Exactly when AJW had originally introduced their Fox Cub models, the specification of the moped became redefined on 1 August 1977, when its official description changed from ‘A machine of engine capacity not exceeding 50cc, and equipped with pedals by means of which it is capable of being propelled’, to ‘A machine of engine capacity not exceeding 50cc, restricted to 30mph, and weighing not over 250kg’. This basically meant that a moped need not now have pedals, but could have footrests and a kick-start instead, though AJW would presumably have already been holding stock, or be contractually committed to some quantity of the pedal Minarelli engines, so would have continued to offer their Fox Cub in both versions to try to clear obligated stock. By the time of the Kestrel’s first appearance in August 1980, the new 30mph restricted kick-start & footrest moped formula was becoming the norm, so the new standard arrangement was obviously favoured.

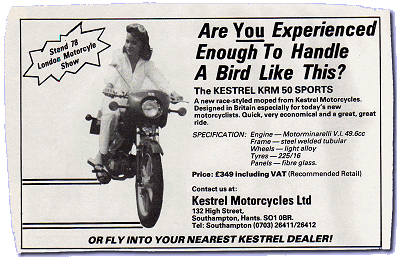

The following month an advert appeared in the September 1980 edition of Motorcycle Mechanics, illustrating a different coloured Kestrel machine fitted with indicators, quoting a confirming specification of the Minarelli V1 (automatic) engine, and advising a wheel & tyre size of 2.25 × 16, but also on the advert ‘Stand 78 London Motorcycle Show’, so Kestrel looked to be going to Earls Court…

Three Kestrel models were indeed shown at Earls Court, one white, one green, and one red; these were all prototypes based on the earlier fabricated AJW frame.

At the Earls Court Show, Kestrel handed out printed promotional cards for the KRM50, which basically followed the information already given, and specified alloy wheels with 2.25 × 16 tyres (notably a smaller size than the 2.25 × 17 diameter wheels & tyres on the AJW Fox Cub).

Subsequent to the show, a moped feature on Kestrel appeared in Bike magazine, December 1980 edition, including motor cycling press impressions of a black Kestrel sports moped with a four-speed foot change Morini Franco motor of the same type formerly fitted to the now extinct NVT Easy Rider Sports ER-4 models.

This is the first time we’ve actually confronted a real live Kestrel, now over 30 years old, and you don’t see many about (we’re not sure there were ever many about in the first place), so we’re keen to take the opportunity to check it out. The fuel tank looks interesting since it doesn’t have a filler cap, and is obviously a fibreglass ‘box’ with a lid. Unclip the two latches at the front, and the top comes off to reveal a steel tank housed within, and enough space in the front of the compartment to house some service tools.

The front forks look familiar and, within the fairing, the headlamp & speedometer mounting assembly confirms that this seems to be the same front end set as fitted to Tomos A3 models. The speedometer however is a 40mph CEV, as also are the headlamp, tail lamp, and simple moped-type AC switchgear. Though a steering lock is fitted to the headstock, there is notably no ignition key-switch, so the engine is simply stopped by a plain cut-out button on the light switch.

There’s a frame plate riveted to the headstock, reading ‘Manufactured by LEM Motor Italy for Kestrel Motorcycles Ltd, moped, 110lbs, frame number 010460’, and a manufactured date of 24.03.80.

The fitted alloy wheels & tyres are 2.50 × 16 on the front and 2.75 × 16 on the rear, which are obviously a different tyre size than quoted in the literature. We figure these tyres might have been changed, since both fitted tyres appear slightly too wide as the front tread pattern grazes slightly on its mudguard bracket, and the rear lightly brushes the lower chain run with its outside edge. The alloy wheels look to have worryingly small diameter brake hubs, so we make a mental note of that for the road test later.

The Minarelli V1 automatic motor has a fan-cooled cast iron cylinder with an air-cooled aluminium head. Specifications are given as 38.8mm bore × 42mm stoke for 49.7cc with 12:1 compression ratio and quoted 1.7bhp @ 6,500rpm. The plastic moulded fan-cool ducting looks pretty cheap and tacky—cast alloy might have looked so much nicer, but that was the way things were starting to go.

All the fibreglass mouldings probably seem a little bizarre to any modern biker, but fibreglass was the lightweight material of the day, before the advance of the large-scale plastic moulding technology that now cloaks motor cycles of the 21st century. Kestrel looks like a small sports motor cycle, but works like the most simple twist-and-go moped. Cock the fuel tap, off–on–reserve, click down the choke on the Dell’orto SHA12-14 carburettor, just a couple of jabs on the kick-start has the motor fired up, then fully wind back the twistgrip to snap off the choke. Hold the throttle on a little to clear its throat, and within just a few more seconds the engine is already running clean and ready to go. The exhaust note is sharp and crisp, which PC Muscleneck might even call ‘loud and intrusive’, but there is clearly a baffle in there, so we think it must be OK, officer.

Roll out onto the road and gun the throttle for lots of revving and even more noise as the motor comes under load against the slipping auto-clutch, but there’s not half so much acceleration as revving and noise. Initial progress is so sluggish that you’d probably want to assist, if it only had a pedal set, so in reality the best you may offer is a scoot with one leg. The relatively slow progress continues up to 20 on the dial till the clutch fully bites, when the motor pulls pretty well from then on.

Turning onto the main road, the usual exchanges with the pace bike confirm our speedometer is reading reasonably accurately at 20, so we ease ahead to settle around a comfortable cruising rate up to 30mph and warm the motor on this outward leg.

The relatively long tank and straight-ish handlebars present a mildly forward riding position, slightly sporty, and easy to tuck down into a crouch. A confident and purposeful stance that was also comfortable to ride … we’re quite getting into the feel of this bike already.

As speed starts to creep above 33mph on the clock, clean combustion breaks into some bluster of four-stroking that only eases if you back off the throttle slightly or rise a slight incline. The already noisy exhaust becomes particularly crackly and aggressive, an observation later raised by our following pace rider. This is typically an effect of a restricted exhaust porting failing to clear burnt gas, though it can improve slightly when the motor gets thoroughly hot.

Compensating for the poor acceleration phase up to 20, there’s a conscious effort to adjust your riding style and dive through corners to keep the speed up, which Kestrel handles fairly well, so it’s generally possible to maintain a good average pace unless you have to pull up at a junction—where you find out how truly poor the brakes are!

The left lever has a spongy and useless feel that pulls right up to the grip for very little retarding effect from the back brake. The right lever is slightly better, it feels like a brake, but proves well below acceptable, and creaks as the bike finally slows to a halt. Kestrel goes far better than it stops!

Our CEV speedometer proved reasonably accurate up to an indicated 35, above which the needle began to bounce & swing about, and wasn’t so convincing.

Charging into our downhill run, tucked behind the fairing with the exhaust snarling ferociously through its four-stroking dive, and the needle waving somewhere around the end of the dial, our pace bike clocked maximum speed 39, maybe just glimpsing 40 through the dip as Kestrel went on to attack the following hill climb. As soon as the motor came under load on the ascent, the four-stroking went off like a switch being thrown, and you could feel the little Minarelli engine really dig into the task ahead. As the exhaust note smoothed out to a resonant two-stroke purr, you could tell the V1 was out to give a good account of itself on this job, and Kestrel crested the rise at 31mph—what a cracking show that was for an automatic!

After that, we pushed the Kestrel through some pretty hard riding on the return leg, mostly keeping up the pace to avoid the automatic dead-zone, and clocked our best on flat reading paced at 36mph in still air and tucked down behind the screen, with the engine thoroughly hot.

The Kestrel proved a lot better riding machine than would probably be expected from an automatic moped motor, and handling was good enough to push the bike along at a pace. The poor acceleration phase up to 20mph counted against it, and the small hub brakes were woefully inadequate. Four-stroking issues with the engine could be resolved with a little careful tuning, which would certainly improve general running and probably smooth out the angry exhaust tone. Despite the obvious shortcomings, overall we quite liked riding the Kestrel: the sports styling is quirky and interesting, surviving machines are infrequent and unusual—and honestly, we’d probably chose a Kestrel over many of its contemporary 70s’ & 80s’ automatic moped stable mates. Slo-ped restricted to maximum 30mph? Well it’s certainly still in standard trim, and didn’t seem too performance limited to us. There’s maybe a feeling the specification plates were just tacked onto some of these old mopeds without too much concern about actual compliance in the early years of changed regulations.

In the New Year of 1981, everything went very quiet on the Kestrel front, and as time ticked into the spring … then summer … it was becoming apparent the bird wasn’t coming home to roost. Kestrel disappeared, and was never seen nor heard of again.

According to reports from a former salesman who worked for Kestrel, after having completed all its prototype models and seemingly being ready to go into production, the company apparently did a final costing assessment and decided that after buying the components and assembling the bikes, the project left little margin for profit, so they aborted the whole idea at the 12th hour and reportedly only sold about a couple of dozen various pre-production machines.