Towards the mid-1960s, Motobécane had firmly established its position in the general moped market, but was looking to expand its spectrum by production of a super-cheap and basic moped particularly intended for the teenage market.

Isodyne

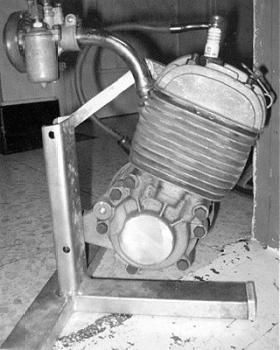

The idea behind the Isodyne (from the Greek words isos equal and dunamis power) engine was to produce a more even power output across the rev range. This was to limit the maximum speed of the Cady while still giving it a reasonable hill-climbing ability. The long inlet was a part of the Isodyne system and the pictue below shows a prototype Isodyne engine used to test the principle.

Their first prototype engine comprised a conventional ‘full crankshaft’ motor, with normal inlet arranged at the back of the cylinder, but when the M1 Motobécane Cady (or C1 Cady for Motoconfort branded versions) was launched in 1965, ‘Mines’ certification recorded its new ‘Isodyne’ motor with a very low power specification rated 1bhp @ at 3,600rpm, max torque quoted at 2,000rpm, and max revs at 4,300. The new model was equipped with 19-inch wheels in a rigid frame with rigid fork, and described a coupled throttle and front brake control, so a touch on the brake lever would shut down the throttle. Maximum speed for the M1 was quoted at 33km/h, and the cycle was standardly finished in burgundy paint.

There has been quite some speculation as to whether the Cady was aimed to compete against VéloSoleX sales, but the VéloSoleX seemed more inclined toward an older demographic, so direct market competition didn’t seem to be the intention.

It turned out however that Cady’s cheapness and lightweight would also have an appeal to older customers, particularly women in the 30 to 50 age group, so whether intended or not, the Cady was positioned to take a chunk out of VéloSoleX sales.

Another prototype Cady roller-drive CM model was briefly entertained in 1967, which would have seemed to be more specifically intended toward the VéloSoleX market, but this failed to secure production approval. Instead, at the October 1967 Paris Salon, Motobécane presented a new M1P (P = Pliant / folding) Cady version with smaller 16-inch wheels and headlamp mounted on the front mudguard, finished in the same burgundy colour and fitted with the same Isodyne engine. The quoted speed of 31.5km/h was presumably due to a lower drive ratio. Presented at the same event was an M1PR (PR = Petites Roues / small 16-inch wheels) model with rigid fork, and quoted a max speed of 31.7km/h. Motoconfort presented the same Cady models, though again prefixed with a C instead of an M.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, the M1 Cady was listed by Motor Imports Ltd starting from the Earls Court Show in November 1966, in preparation for the beginning of the next sales season in spring 1967.

Cady’s listed price at launch was posted at £51–19s–6d, while other Mobylette models were advertised as ‘from £55–17s–5d’ so the M1 Cady became their cheapest machine by nearly 14%.

Following devaluation of the pound on 18 November 1967, prices increased to £56–14s–0d for the Cady and £63–0s–0d for the AV42 Minor, which was the next cheapest Mobylette model.

Presenting an article on the Mobylette Cady really demands that we start with a good example of the M1, and this one is right on the button—completely original, and with a 1967 E-registration dating from the first year the model was listed in the UK, it couldn’t be better!

This is obviously a very lightly built bike, and easy to lift, so we lift it straight onto the scales—an all-up weight of just 4 stone 10 pounds, and wet with fuel—at just 66lbs or 30kg, that’s a really light bike!

M1 has rigid forks and a rigid frame, but we spot straight away that there doesn’t appear to be any adjustment at the rear wheel: the pedal chain has its usual arm tensioner, but how do you tension the drive chain? Though the rear spindle is clearly located in a fixed position fork at the bottom of the stay, closer examination reveals ‘long’ holes above to allow the rear stays to pivot and adjust along frame slots to tension the chain. VéloSoleX employed a similar method to adjust the pedal chain on their machines, which Motobécane seemed to have adopted for the Cady main drive chain, so we wonder how many other Solex features might be common with the Cady?

The M1 Cady has 23-inch tyres on 19-inch wheels, but the rims only have 28 spokes in both front and rear (same as the Solex), so they’d be a nightmare to replace, because 19-inch Endrick pattern rims with a 28-hole pierce are an obsolete specification. The rear hub has a tiny 70mm Leleu drum brake, while the front is a cycle calliper with blocks acting on the sides of the rim. The front fork is a lightweight pressed steel U-section with an open back (again, similar to the Solex). What isn’t remotely similar to the Solex, is the Cady engine. It’s mounted in the right place for best balance, low down in the middle of the frame, and viewed from the left side, looks reasonably familiar with an outboard clutch and inboard pulley for belt drive to a larger belt flywheel, which looks to be formed out of … what material? We tap the flywheel with our fingernail, which reveals the component is cast from aluminium! That’s certainly quite unusual, and it has a plastic engagement knob (drive-pedal), where all other Moby models had a pressed steel ‘changer switch’, which would continue on standard moped models for another 20 years yet—so why different components for the Cady? That aluminium belt flywheel is smaller than any other Mobylette models, and then you realise the clutch is smaller too! Those side-panels are also smaller…

There’s clearly been some miniaturisation theme going on here!

The front brake has an odd pivoting bracket built into the handlebar lever assembly… Hmm? Turn the twistgrip, and the throttle opens and closes in the normal way, but pull on the front brake while the throttle is open and the bracket moves to release the throttle cable. We wonder if it might be intended to emulate a similar feature on the Solex control, which engaged a latch on the throttle, and released the latch by brake operation.

Motor cycles generally employ throttle controls which default to the tick-over setting, so need the rider to regulate the speed as appropriate, but the ‘inverted’ Solex ran constant full throttle, and required the rider to regulate its speed by braking. This wasn’t as alarming as it might sound, due to the low power and limited performance of the Solex engine, and its latch-release operated in similar manner to a cruise control of today. The M1 Cady however, has a normal operation twist-grip throttle, so the coupled brake–throttle shutdown mechanism would seem a completely pointless feature?

We also note there’s no forward decompress action with this special Cady throttle control, so the decompresser is worked by what would normally be the choke trigger under the left-hand bar … so where’s the choke? Ahh, there it is, another little trigger tucked inaccessibly away amongst a nest of cables by the steering headset. That looks like quite an inconveniently located control to operate when you’re trying to start the bike! We try the trigger and find it stays in whatever set position you put it in, which is probably just as well, since it’d be very difficult to work if it sprang back like the normal trigger chokes do.

Then you notice an odd pipe coming from under the left-hand side-panel, going round the left-hand cylinder fins, and entering the cylinder next to the exhaust pipe … what’s that about?

Look round the right-hand side of the motor—and it’s just a blank crankcase cover, which means M1 has an overhung crank … so where’s the magneto? Ahh, there it is, behind the drive belt, so you have to take the clutch off to access the ignition set … how crazy is that? We bet the dealers didn’t like it! This is what Motobécane called their Isodyne motor (probably just a trendy new name for an old-fashioned overhung-crank design, with the intake next to the exhaust at the front of the engine, which allowed the space to add a third internal transfer port to the back of the cylinder to improve torque. They probably needed to improve the torque, because the 250mm long inlet pipe of 10mm diameter would mean 40% of the incoming charge from the carburetter would be ‘parked’ in the tube, and out of phase with the induction.

Lots of the screws on the motor were Allen hex-socket bolts, so the engine maybe looked a little technical for the time, though in reality represented a revival of a cheap old concept.

The Cady may look much like any familiar Mobylette of the period, but it’s actually a completely different machine.

Somewhere under the side-panels lurks a 10mm Gurtner carb, so it’s probably going to perform like any other Mobylette … isn’t it? Errr, no … maybe it won’t. Browsing the technical data, it doesn’t sound so exciting … Cady M1 with Isodyne motor with 8:1 compression ratio, rated 1bhp @ 3,600rpm and given max speed 33km/h—which is just a bit over 20mph.

Starting is similar to other Mobylettes, but with some of the controls in a slightly different arrangement. Push down the fuel tap for on at bottom right inside the frame rail. Pull up the choke trigger at the headstock, thumb on the decompresser trigger under the left bar; on the stand, kick down the pedal to spin the engine and release the decompresser. No, it doesn’t start. We try again—no. And again—no. Ok, let’s try it with a bit of throttle on—no. With a lot of throttle on—no. Without the choke—no. OK, let’s pedal it up the road, decompresser on to get the engine spinning, release the trigger and keep pedalling, twisting open the throttle, still not firing, try it without the choke on and keep pedalling… Chug … chug … chug … chug—yes, Cady splutters into life, hooray!

It feels very ‘gentle’ with feeble power pulses … you can readily tell that this is a low power motor. We run the engine for a minute while our pacer gets sorted out to follow us, then ease softly away on full throttle. Cady crawls up to a slow speed (we don’t know what because it has no speedometer, but it’s definitely not fast in any way—we’re not sure we’d even describe this as acceleration), then it seems to run out of steam at cycling pace.

As we leave the village, there’s a gentle uphill slope that Cady snivels up at 18mph as our pacer pulls up beside to urge us along with a ‘Come on then!’

‘I can’t, this is all it does, it’s flat out!’

If the Cady came across a real incline you’d certainly expect to be pedalling it up.

Levelling out at the top, we tuck down along the straight in still air to clock a best on flat of 22mph, then turn around for the return leg, and fold into the tightest aerodynamic form we can for the downhill run. Strongly assisted by the pull of gravity, Cady manages to hit the dizzying heights of 26mph. At this speed, vibration from the motor is typical of an overhung crank engine running beyond its comfort range, and the extra speed falls off immediately as we level back onto the flat.

M1 Cady’s performance is so feeble that it feels like travelling in slow motion.

The 70mm Leleu rear drum brake returned a soggy feel at the lever and delivered only a gradual retarding effect, while the calliper front brake was creaky and ineffective—though it’s not as if much braking was really needed, because the bike was so slow.

Lights turn on by a slide switch on the headlamp, which is only equipped with a basic filament bulb, and there’s no electric horn on this model, just a basic bulb hooter was fitted because Cady was designed on a very low budget.

A telescopic fork Cady was planned for display at the Paris Salon in 1968, but industrial action at Motobécane delayed its appearance until January 1969.

This delayed M1PRT (PR = Petites Roues / small 16-inch wheels, T = Téléscopique / tele fork) model was released in 1969, to subsequently succeed the original rigid fork, 19-inch wheel M1. The austere burgundy paintwork of the M1 was also swept away, as the new bike was presented in brighter colours of red, blue, white, and topaz, though it still continued with the same overhung-crank Isodyne engine.

M1 Cady imports to the UK ended in November 1969 as stocks of the original model ran out.

The rigid frame M1PRT was soon joined by another small-wheel model in January 1970; the M1PRTS (S = Suspension arrière / rear suspension) had a new swing-arm sprung frame.

New Cady M3PRT Commuter and M3PRTS Commuter De Luxe models were listed for UK importation from April 1974, which presented a change to a new ‘Super-Isodyne’ engine. The new motor was apparently rated exactly the same 1bhp @ 3,600rpm general specification as the previous engine, and differed only in replacement of the original overhung crank design with a conventional twin-flywheel configuration crank supported by a short journal and bearing on the crankcase cover side.

Comparison of M1 and M3 engines

M1PRT & M1PRTS listings were both formally withdrawn in August 1974, presumably as the last stocks of the old Isodyne motor models had become exhausted at the factory, at which point they became officially succeeded by new M3PRT and M3PRTS models.

Also released in August 1974, was a third model: M3PRTSG (G = Graissage séparé / Pozilube).

Our second Cady tester is a 1975 P-registration rigid-frame machine with small wheels, where much of the detail has faded from the headstock plate on this bike, and is mostly unreadable, but the model is an M3PRT with the new Super-Isodyne engine.

This certainly looks a small machine, so out with the tape, and it measures up at just 61½ inches from the taillight lens to the tip of the front wheel. Saddle height is 31 inches, and handlebar height is 40 inches, so they’re fairly conventional measurements—it’s just the short length that makes it appear strikingly small. We guess you might describe it as short and stubby? It’s like an odd shrunken version of a moped!

Because of the physically small size of this bike you do start wondering how many of its components might be special miniaturised versions of standard parts?

The length of the front forks appears normal, though there’s a special bracket welded to the top yoke to bolt up to a location pin through the handlebars and set them into a fixed position … so, special top yoke and handlebars.

The front and rear hubs are tiny 70mm Atom 28-hole, so they’re not going to be common with any other Mobylette types. This model has unique 16-inch rims with a 28-hole pierce, and fitted with 2.25 × 16 tyres, so you’d certainly find it extremely difficult to source replacement rims of that specification today.

The rear hub is fitted with a dished 36-tooth sprocket, but would be of no consolation to Wisp owners after that size since this sprocket only has a 72mm centre bore with a 4-bolt fixing, so it won’t fit anything else (Wisp uses 94mm bore with 6-bolt fixing).

The pedal chain-wheel is a conventional flat, pierced sprocket, but because of the diminutive stature of the machine, the pedal arms have to be shorter to reduce the risk of grounding, just 125mm centres.

The rigid rear frame is a similar (though smaller) version of the M1 set-up, with the same pivoting-fork arrangement for drive chain adjustment.

The saddle stem clamp has a quick release lever, so is presumably intended for easy saddle height adjustment without tools, or to be readily removable for compact stowage.

The small belt flywheel, measuring just 180mm diameter, is now made out of a pressed-steel welded assembly, with a plastic pedal/motor engagement switch.

This M3PRT Cady has a Luxor 118 headlamp shell with the option to install a speedometer, but the socket is closed by a blanking plate, suggesting a speedo was probably not a standard fitment on this budget model.

An electric horn now appears standard equipment and is fitted beneath the headlamp nacelle. On this example the original horn seems to have expired, though it still remains in place, and another functioning pattern horn has beed attached on the right, below the headstock.

The delicate legs of the pressed steel stand seem as if they’re only intended to stand the machine on, and really don’t look as if they’d withstand any pedalling on the bike without bending, so starting is either going to be down to the ‘kick-start technique’, or a flying start up the road.

In deference to the flimsy looking stand, we opt for the ‘flying start’, so: fuel on, engage the decompresser, pedal away, engine spins, drop the decompresser and keep pedalling … no go—so thumb the choke trigger, and it fires right up. We cruise gently along the road getting a general feel for the bike while flicking the choke trigger a couple of times till the engine runs clear without wanting any more, and the motor is ticking over steadily already.

Like the earlier M1, power-pulses don’t feel overly powerful, so we do wonder if the Super-Isodyne motor is really much more ‘Super’?

Opening the throttle, it responds with a familiar feeble effort as we slip into gentle motion, and it’s clear that a little pedal assistance would still be appreciated to improve the getaway, then we experience the usual single-speed Mobylette type bottom-end flat spot as the clutch lumps in. The Super-Isodyne Cady is still a low power moped that still wants a bit of rider input to get underway.

Once through the initial phase, the motor feels to deliver moderate torque from low revs, and acceleration feels somewhat better than expected, up to a comfortable cruising speed generally less than 25mph, because a degree of increasing vibration starts to filter through around this point, and the vibration becomes progressively more intrusive beyond 25.

Our light uphill climb dropped the speed back to 23mph, which the bike managed competently without any need for assistance.

It’s immediately obvious that the Super-Isodyne motor is certainly a performance improvement on the original overhung crank design, because we can readily get up to much the same speed along the flat as our M1 Cady could only manage downhill.

Another issue is, however, revealed at speed as soon as you run over a section of bumpy road, because you certainly feel the jolts through the geometry of this small rigid frame. Maybe it’s because you’re sitting right on top of the rear wheel, but it doesn’t take long before the battle fatigue starts setting in!

The only real answer to the vibration and battering is to ride a little slower, and things become much more comfortable cruising at 20–22mph.

Along the flat our pacer clocked us off maintaining 26mph in an upright stance, and adopting a crouch could further raise this up to 28–29mph, though this extra 2–3mph would readily drop away again when sitting upright, so the Super-Isodyne motor couldn’t generate enough power to hold the extra speed.

Best light downhill run in a crouch paced at 30mph, but with a fair level of vibration now suggesting the motor was ‘over its edge’. Engine revs had obviously topped—out, and that was all we would reasonably expect it to do.

The third and final Cady tester of our set is a sprung frame machine with small wheels, where the headstock plate shows ‘M1PRTS’ and ‘5–11–1969’, indicating the date the first Cady small-wheel suspension model frame was recorded … and this doesn’t really reflect the 1976 P-registration machine we actually have here, because this is absolutely an M3PRTS since the engine is certainly the ‘Super Isodyne’.

It’s apparent this Cady model is also quite a tiny bike, like another moped in miniature, so we roll out the tape to measure its length, nose to tail, same 61½ inches as the rigid frame PRT version, and on the scales (with fuel in the tank), less than 6 stone, just 83lb, or 37kg if you prefer. That’s a pretty small bike, which might appear a little undersized for some riders…

The front-end aspects appear the same as the PRT model, but as you look toward the back of the bike, then things start to change … because this Cady has a conventional twin-shock rear suspension and it’s quite neat how they managed to trick this into the same limited space.

The rear swing-arm looks shorter than normally expected on 50V models, and since the 16-inch tyre appears to be closely nestling into the crook of the swing-arm, it doesn’t look like you’d be getting any 17-inch wheel in there, so the Cady swing-arm must be smaller. The rear shocks also seem shorter, so a quick measure indicates them to be 250mm centres, as opposed to conventional 50V rear shocks at 300mm normal length.

This saddle stem clamp also has a quick release lever, so presumably also intended for ready saddle height adjustment without tools, or to be readily removable for compact stowage.

The PRTS pedal chain-wheel comprises an unusual pressed-steel dome welded to the pedal shaft as an assembly, which we figure might be a necessary change to clear the swing-arm pivot behind it. The bike is so small and compact that its construction obviously required a little more imagination.

Despite the additional engineering of rear suspension with a lot of special parts, the PRTS is still a small and light machine.

Kick-starting on the stand is very similar to most Mobylette models, with a push-on petrol tap to the right-hand side.

The Cady twist-grip throttle still doesn’t have the usual forward decompress action, instead featuring a thumb trigger below the lever set to operate the decompresser, while the choke still operates on the usual left-hand side trigger. Press down on a pedal to get the motor spinning, then release the decompresser trigger, and she fires up first time! The starting was easy, though we do need to keep feathering the choke trigger for a little while or the engine threatens to die out. Within a minute the motor manages to run without the choke, so we leave it ticking over to warm while we get our helmet and gloves, and muster the pace vehicle.

Though the M3PRTS Cady has the same Luxor 118 headlamp shell with option to install a speedometer, the socket is again closed by a blanking plate, so despite this being the top model, we conclude a speedo may never have become standard fitting on any type of Cady throughout the entire production run?

Apart from the usual single-speed Mobylette type bottom-end flat spot as the clutch lumps in, the motor feels to deliver capable torque from low revs, and acceleration again feels rather better than expected (compared against the old Isodyne motor), up to a comfortable flat cruising speed around 25mph with minimal vibration.

Our pacer clocked 27mph in an upright stance along the flat, 33mph in a crouch on the light downhill run, and dropping down to 24mph against the light uphill gradient.

Immediately it’s apparent that there’s appreciably less vibration than with its rigid frame cousin, and the same section of road that battered us around on the PRT seems a much easier ride with that extra letter …. S = suspension!

This M3PRTS rode much more comfortably than the rigid frame version, and certainly vibrated less, though it might be difficult to attribute less vibration to the sprung frame itself, but more possibly differences between individual engines and their installation.

Considering the original M1 Cady’s slow performance reputation with its Isodyne motor, we were very surprised to find both the M3 Super-Isodynes readily went much better on test, managing up to 27mph along the flat, and up to 33mph paced on the light downhill run. All other aspects of the two motor types remained identical, with exactly the same cylinders, porting configuration, pistons, compression ratio, and carburettors. The only difference between the early and late motors is the crankshaft arrangement, overhung crank versus twin journal crank, while all other aspects of the engines are identical, so this clearly illustrates what an improvement the crankshaft design can make.

Officially, the Cady name was dropped after January 1976, though all the same models continued, their tankside decals displayed ‘Moby’ instead. Final listings for M3 models were posted in August 1977, when the range was replaced by the 7 series.

Motobécane had earlier produced a prototype with the Super-Isodyne motor adapted into a frame similar to the 7-series, but seemingly decided against continuing with the 1bhp engine type.