Towards the tail end of the reign of Queen Victoria, North America might still have been perceived as the wild-west, but the continent was changing rapidly, industrialising, and well on the way to evolving as a new global super power.

Former bicycle racer George M Hendee established his Hendee Manufacturing Company in his hometown of Springfield, Massachusetts in 1897, for the purpose of building bicycles. These were initially badged as Silver King and Silver Queen (presumably indicating gent’s and lady’s style frames), then American Indian, and finally shortened to just Indian brand for 1898 to enable better product recognition for export.

Hendee was joined in 1900 by Carl Oscar Hedström, also a former cycle racer and manufacturer, and with Hedström working as designer and chief engineer, the company produced its first motor cycle with a 1¾hp single-cylinder engine in 1901. Two diamond framed test models were subsequently built and tried before the first production motor cycles went on public sale in 1902.

With a streamlined design and chain drive, the bikes were intended to be robust and fast, and the following year found Hedström claiming to have established the world motor cycle speed record at 56mph.

From the manufacture of 500 motor cycles in 1904, and winning the first three places at the 1911 Isle of Man TT races in 1911, production had risen to a peak of 32,000 machines by 1913, at which point the Indian Motorcycle Co would briefly seem to have become the biggest motor cycle manufacturer in the world.

Indian had reached the pinnacle, but time on the summit wasn’t to last long...

Indian Papoose

Carl Hedström left Indian in 1913 after disagreements with the Board of Directors regarding dubious practices to inflate the company's stock values. The Great War intervened, and George Hendee resigned in 1916, while most of the product was being supplied to the government and military, at the cost of domestic sales, which were taken up by competitor Harley-Davidson.

Despite losing prime initiative, Indian retained a very significant market share upto and through the Second World War, when control of the company passed from Du Pont, who had secured the business in 1930, to Rogers Group in 1945, which began the start of a steady decline towards the conclusion of production and bankruptcy in 1953.

At the collapse of the Indian company, Brockhouse Engineering of Southport in Lancashire and manufacturer of the Corgi mini-bike, acquired rights to the name. Brockhouse had established a trading relationship with the Indian Company in the early post-war years. Corgis were sold into the US as the Papoose model under Indian branding, and Indian Brockhouse 250 Braves were sold in both UK and US markets from 1950–55.

Brockhouse then continued selling practically the full range of Royal Enfield motor cycle models from the 150cc Ensign two-stroke single to the 700cc Constellation four-stroke twin, badged as various Indian models for the US market, and occasional AMC Matchless motorcycles with Indian branding.

In 1960, the Indian branding rights were bought by Associated Motor Cycles, with the intention of securing additional export of AJS, Matchless & Norton machines into the US under Indian branding, mainly by replacing the sales of their competitor’s (Royal Enfield) motor cycles. Except for the largest 700cc capacity, Enfield/Indian models were replaced practically overnight by AMC/Indian equivalents, but the amount of Enfield stock across the Indian distribution network would take time to clear, so a confusing selection of various models was being cleared across the US for a few years ... by which time AMC was sliding towards deep financial problems and final bankruptcy of the group in 1966.

Manganese Bronze Holdings Ltd bought the collapsed remains of the Associated Motor Cycles empire, including the rights to Norton, AJS, Matchless, Francis-Barnett, and James motor cycles, which were combined with their other existing motor cycle related business under the new business name of Norton-Villiers.

In the confusion following the AMC business collapse, Indian branding was seemingly ‘unofficially adopted’ by American entrepreneur Floyd Clymer, who attached it to imported Italjet mini-bikes with 50cc Minarelli engines and popularly sold these as new ‘Indian Papoose’ models, as well as returning to more Indian-branded Royal Enfield and Velocette-engined models with Italjet designed and manufactured frames.

Following Clymer’s death in 1970, his widow sold on the ‘alleged’ Indian trademark to Los Angeles attorney Alan Newman, who continued importation and marketing of the Italjet models under Indian branding, and established an assembly plant in Taiwan to manufacture and supply mini-bikes, mopeds, and light motor cycles from 50cc to 175cc using Italian Morini-Franco or Minarelli engines. By 1975 however, sales were fizzling out, and the company was declared bankrupt in January 1977.

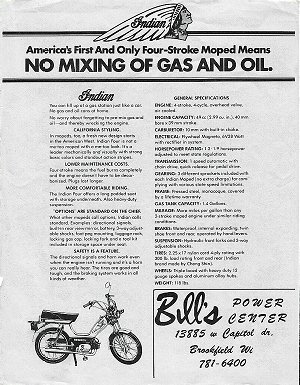

Later in the same year, the Indian name was purchased from the bankruptcy court for $10,000 by American Moped Associates, who planned to continue to employ the Taiwanese manufacturing plant to make a new moped...

Across the East China Sea in Japan, Honda had decided to discontinue its old four-stroke mopeds and replace these with new two-stroke models. Following a 10-year production run, the PC50-K1 was pensioned off in February 1977 ... but the engine design and a number of cycle ancillary components were licensed on to AMA to manufacture again at their Merida factory in Taiwan.

The result was the Indian AMI-50 ‘Chief’, which first appeared on sale in 1978.

Now it’s fairly obvious there are some people who’re going to say this is just a PC50 come back to haunt us, but it’s really not! The engine is clearly a mirror design, but absolutely everything has been re-made, and not a single original Japanese Honda PC50 component or fitment has been employed. It’s a completely new motor manufactured to the licensed blueprint, and everything is different.

So let’s have a look round our test feature bike dating from 1979... well, the cycle chassis is a pressed steel welded assembly with the fuel tank in-frame, and finished in a smart metallic red paint, nice looking telescopic fork set at the front, and swing-arm suspension at the rear. The body is topped with a generous 22-inch long dual seat, with rear footrest mounting points let into the swing-arm if you might be inclined to complete a two-seater conversion, so there’s a confident impression that the motor should pull well. A screw-locked sprung catch at the back of the seat pulls back to release the base to hinge upward and reveal a very generous full-length tool tray beneath.

Behind the plastic side panels are a small 6-Volt battery on the right-hand side with an Indian graphic printed on this, obviously original, component; a bundle of wiring; and the flasher relay. The left-hand panel covers the 10mm Mikuni carburettor, which breathes through an identical copy of the PC50 air filter housing and assembly.

A tubular steel and chrome plated carrier loops round the back of the rear mudguard for mutual support, and attached by a lower rail to support fitment of panniers.

Indicator stems mount off the rear carrier frame, and again up front from either side of the chrome headlamp brackets. The indicators themselves look a very familiar old-style Honda pattern, but examine the amber lenses and the Indian logo is actually moulded into the plastic!

There’s a nice chrome headlamp with 4-inch diameter lens, and moving on to the control gear, the left-hand brake cluster has a light switch off/on (American market mopeds only have a single filament lamp with no dip beam), horn button, and a decompressor lever below. The right-hand throttle/brake cluster has left/right indicator switch, and engine stop switch (no key-locking ignition).

Both left and right hand-brakes have in-built stop lamp switches in the lever brackets, so the brake light will operate on both front and back braking.

The Tatung Co speedometer is marked to 50mph for the American market, with a secondary graduation scale to 80km/h, and only shows just over a genuine 2,000 miles on the counter, so we might expect this to be a fairly representative example for our test.

Wheels & tyres are 2.25×17 on good looking chrome rims laced onto full width hub brakes.

Starting the Indian is fairly similar to a PC50, though the fuel tap is at bottom right of the tank, reserve/off/on, just to confuse you. The original PC50 Kei-Hin carburettor had a shutter-choke operated by a little lever off the carburettor, but the Indian 10mm Mikuni carburettor has a pad-choke operated by cable from a trigger under the right handlebar cluster. A disadvantage with this arrangement is that a pad-choke is either off or on, with no option of variable in-between setting like a shutter choke, so we expect to be ‘feathering’ the trigger for a while until the motor warms to run.

Unlike the neat PC50 ‘thumb-trigger’ decompresser, the Indian decompresser control is a clumsy and overly large plastic lever under the left handlebar cluster. PC50 engine decompression has a light action and doesn’t actually require an enormous lever as may have typically been found on the mighty old side-valve V-twins—perhaps there’s some traditional influence hanging on there, but it’s unnecessary on a moped, and not as neat to operate as a little thumb trigger.

The same little ‘engine drive switch’ on the right-hand crankcase cover needs to be switched ‘on’ from pedal mode to enable the engine to turn. Spin the pedals and the engine fires, but splutters out, and needs several attempts with feathering of the choke trigger before we manage to keep the engine running on. The choke needs lots of feathering in this initial phase, and we do have to run the motor for quite a while to warm up enough to keep it going without any choke, so there are no quick getaways in the morning with this Indian. The original Honda shutter-choke arrangement was definitely better.

The exhaust note is quite pleasant, reasonably muffled but having a sharper sounding punch, without being intrusive—we quite like that.

Nudge Indian off its centre stand, and the legs don’t really spring back up properly. The spring doesn’t look particularly stretched or anything but the stand seems a bit stiff on the pivot, so we expect that a previous owner has probably been pedalling it up on the stand, which never does them much good-though with only 2,000 miles on the clock we’re surprised it’s got mashed so quickly.

Same as the original Honda motor, the automatic clutch engages with a lump, and there’s an initial flat spot until the engine manages to struggle up some revs, then acceleration seems maybe a little better than the PC50, though you soon realise this is probably because the Indian feels to be lower geared, since it’s revving quite angrily before you’ve even got to 25 on the clock! A brief exchange with our pace bike rider soon revealed the situation to be deeper than that, since we quickly established the Indian speedo was reading a little fast—25 was actually just 21!

Vibrations through the pedals were already very noticeable—and you certainly wouldn’t get that level of vibration from a Honda engine. Honda engines run smoothly, but the Indian was growly and harsh.

Turning onto the main road is where the AMI-50 proves to be really lacking, with a best on flat reading of 27 to 28 and an actual speed of just 24, while the motor was snarling angrily due to over revving from its low gearing (a brief diversion to assess the drive ratio: PC50 had a 15-tooth front sprocket, driving a 29-tooth rear sprocket, with 2.00×19 tyres; Indian has a 14-tooth front sprocket, driving a 28-tooth rear sprocket with 2.25×17 tyres. To save you all the painful mathematics, the Indian is pitched 10% lower than standard PC50 gearing), but it soon became apparent that the Indian’s limitations didn’t end with the drive ratio!

You’d normally expect a bike with a low drive ratio to be more capable against a hill, but the Indian readily faded on just a mild incline, indicating the motor also being down on expected power. The Honda PC50 was rated 1.8bhp, but this Taiwanese shadow of the original was very clearly producing rather less than this, which is maybe why the Indian engine was kitted with a lower drive gear-because it wasn’t up to the job?

Quite a bit of this power was obviously being lost in rough running and vibration because the engine build quality wasn’t good enough, and overall these factors would probably work against the Indian to drive it to an early grave. We also noted a smoky presence in the exhaust from some trace of burning oil, so maybe the cylinder bore and piston ring quality weren’t up to Honda’s standard either?

Whipping our pony to a frenzy for the downhill canter just about saw 30 on the speedo, while the shadowing pace bike clocked this maximum off at just 28mph. This speed was clearly beyond any engine revs this nasty motor wanted to run-it really wasn’t happy, and the following uphill climb came as some relief as the revs faded away into the ascent ... and faded ... and faded some more. There was some thinking that it may even grind to a stop, but we kept the throttle on and struggled over the crest at just 16mph. A thoroughly miserable performance that might not seem too dissimilar to some antique cyclemotors from the early 1950s.

General handling and cornering were OK, though a little sloshy, but the shiny cover of the dual-seat was particularly annoying since you constantly slid around on its glossy surface.

Assisted by a 6V battery, the indicators worked OK, but the horn proved so feeble that you could barely hear it, the pace bike rider commented that the brake light seemed to be constantly flickering from even the slightest touch on either of the levers, and the general lights came on when you flicked the switch—but we didn’t really care any more by then, since riding the Indian had been such a disappointment.

Equipping the machine with a dual-seat and pillion footrest mounting points on the rear swing-arm was little more than a flight of fancy by the marketing people of American Moped Associates—the pathetic engine never had any capability of pulling two people!

It’s an awful machine, simply due to the poor manufacturing quality.

We can just be grateful it was only sold into the American market.

Spoked wheels were replaced by cast alloy wheels for production from 1980.

American Moped Associates reportedly planned introduction of a two-speed transmission for the Indian mopeds in 1981, but this never came to fruition. Indian distributors frequently took to complaining about lack of stock and supply, while AMA excused the situation by always saying they were completely sold out. This might have been credible for a quality and popular moped representing good value for money, built to a standard comparable with Puch and Motobécane but, sadly, the Indian was none of these things—and bad reputations get around, so maybe the Indian moped was actually a tough sell! A more likely reason for the stock-outs was most probably supply issues from the Merida manufacturing plant in Taiwan.

AMA’s further daydreams for a new Indian moped and larger Indian motor cycle for 1984 completely evaporated as they chose instead to sell off the business to Carmen DeLeone’s DMCA (Derbi) group in 1982, who really only bought the company out to secure use of the Indian name for their own intentions, promptly discounted the remaining moped stock to clear it out, and discontinued manufacture.

As it worked out, only a few miserable Derbi-Manco go-carts were stickered-up and sold with ‘4-stroke Indian’ branding, before the Indian badge disappeared from all motorised vehicles from 1984.

On through the later 1980s and into the 1990s the Indian logo continued as little more than a line of branded clothing licensed and marketed by Philip S Zanghi, profits from which were supposedly going towards raising funds to finance production of a new Indian motor cycle. Meanwhile, DeLeone progressively transferred the Indian rights across to Zanghi in the early 1990s, who promptly declared himself President and CEO of Indian Motorcycle Manufacturing Co Inc of Berlin, and set about an investment scam to ‘resume’ Indian motor cycle production at East Windsor, Connecticut.

In June 1994, at Albuquerque, New Mexico, Wayne Baughman, president of Indian Motorcycle Manufacturing Incorporated, presented, started, and rode a prototype Indian Century V-Twin Chief. Baughman had made previous statements about building new motor cycles under the Indian brand but this was his first appearance with a working motor cycle.

Neither Zanghi nor Baughman began actual production of any motor cycles.

Subsequent challenges regarding ownership to the Indian trademark opened a whole can of worms and resulted in Zanghi’s arrest in June 1996, from which he was charged, and ultimately convicted on 23 counts of securities fraud, tax evasion & money laundering, then sentenced to 7½ years imprisonment in August 1997.

By the time the dust had settled on this latest episode, Indian had probably fallen to its lowest low, but now there was really no telling how long the brand might be bumping along the bottom before a climb back up might begin...

In January 1998, Eller Industries was granted permission to purchase the Indian copyright from receivers of the previous owner, and then contracted Roush Industries to design an engine for their new Indian motor cycle to be built in a new factory to be constructed on Umpqua Indian tribal land at Cow Creek. Three models were shown to the motor cycling press in February 1998, with a public unveiling of the prototype cruiser planned for November, but this was prevented by a restraining order from the receiver under the claim that Eller had failed to meet the terms of its obligations including payment of administrative expenses and presenting a working prototype.

The contract was declared void, and Indian was back to bumping along the bottom again...

The Federal bankruptcy court in Denver, Colorado allowed the sale of the trademark to IMCOA Licensing America Inc in December 1998. The Indian Motorcycle Company of America was formed from the merger of nine companies and began manufacture of new ‘Gilroy Indian’ Chief, Scout, and Spirit models produced from the group member California Motorcycle Company facilities, initially fitting S&S engines, then 1,600cc Powerplus motors from 2002.

This business shortly went into bankruptcy and ceased all its production operations at Gilroy, California on 19th September 2003, so Indian was back to bumping along the bottom again...

On 20th July 2006, the Indian Motorcycle Company was revived yet again, this time largely owned by London-based private equity firm Stellican Ltd. From established bases in Minnesota and North Carolina, the new concern picked up with a small, limited production/specialist manufacturing of the same ‘Gilroy’ Indian Chief model left by the previous company, uprating to a 1,720cc Powerplus motor in 2009.

In 2011, Polaris Industries and parent company of Victory Motorcycles purchased the rights to Indian Motorcycles branding and relocated operations from North Carolina to merge with existing Victory production facilities at Spirit Lake, Iowa. Polaris Victory is a well established, proven and successful builder of good quality big V-twin cruisers, and a new range of Indian models is due to be presented in late 2013, for release and general sale in 2014.

This really might seem like the best opportunity yet for a proper practical return of volume manufactured Indian branded motor cycles.

May we see an Indian moped manufactured ever again? ... Probably not!

Next—Our journey round the world of Cyclemotors, Autocycles and Mopeds resumes as we chase the setting sun across the Pacific Ocean. So far west that we cross the International Date Line, where distant west turns full circle to become the far east, and our setting sun leads us to the land of the rising sun! Finally washing ashore in strange and distant oriental lands, this seems almost as if it’s another world ... like landing on Planet of the Apes!

These bikes have something of a cult following, and we’ve been promising this epic four-bike follow-up feature for a while.

This article appeared in the

July 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & Indian moped photographs ©

2013 M Daniels. Indian Papoose photograph © 2004

A Pattle. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Our first encounter with the Indian moped came at Utrecht in March 2012 and, never having seem one before, we made a fairly thorough examination, thinking it might be our only opportunity since these machines were never exported to Europe as far as we know, so a pretty rare machine on this side of the Atlantic. Moving along, we later found that Paul Kelling (who’d come with us to this event) had dallied behind to do a deal with the trader, so the Indian ended up coming home with us.

The Indian AMI-50 Chief turned up again later in the year, for exhibition on the EACC stand at the Copdock Show at the end of September, and after the event we managed to blag it for a feature ... what a fantastic opportunity!

A whizz through the workshops (carb, ignition and sprucing up) soon had the bike sorted for road-test and photoshoot in October 2012.

The AMI-50 motor looked much like the PC50, because it was a reprint of the Honda design. The Indian moped really looked promising, and we so much wanted it to be every bit as good, maybe even better than the authentic PC500, but sadly it proved to be a massive disappointment ... little more than a poor quality copy of the original Japanese blueprint, which was cheaply made in Taiwan.

We were almost willing the later Indian development to be an improvement and to outperform the real McCoy, but it wasn’t; it fell a very long way short. Which only goes to show - if you want a moped to be like a PC50, and go like a genuine Honda, then you may not find this from some low budget clone made in China.

Almost like some religious belief, all the V-twin traditionalists reflect back to ‘the good old days’ for a prophetic return of a real Indian motor cycle, built again in America—and that may be about to happen!

In 2011, Polaris Industries purchased the Indian Motorcycles brand, and relocated operations from North Carolina, to merge them into existing facilities in Minnesota and Iowa. A new range of Indian Motorcycle models are due to be presented later in 2013 for market sale in 2014.

Indian motor cycle enthusiasts may wholly dismiss practically all the various imported and Indian branded variants that have come and gone over the years since collapse of the original American company and, though the AMI-50 Chief was certainly a disappointing machine, even by moped standards, it was still an episode in the on-going legend that makes up the Indian story.

The Indian moped might have turned out to be a rubbish copy from the original Honda design, but is still as much a part of the Indian history as the Vespa scooters and Vespino mopeds were a part of the Douglas history, though the traditional flat-twin enthusiasts often flatly deny that part of their story in exactly the same way.

It happened, it’s history - and that’s how it was.

Though the Indian required a bit of workshop time to tickle it up to test standard, actual costs were pretty minimal, and sponsorship of the feature was covered with a modest donation by Alex Taylor from Abingdon. We’re sure he’d be proud to have sponsored presentation of a feature on a classic Indian - but maybe not so much this one!