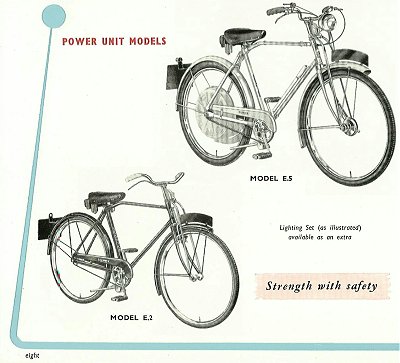

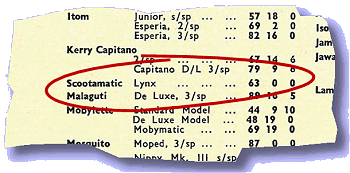

The cyclemotor cycles in the 1955 Elswick catalogue

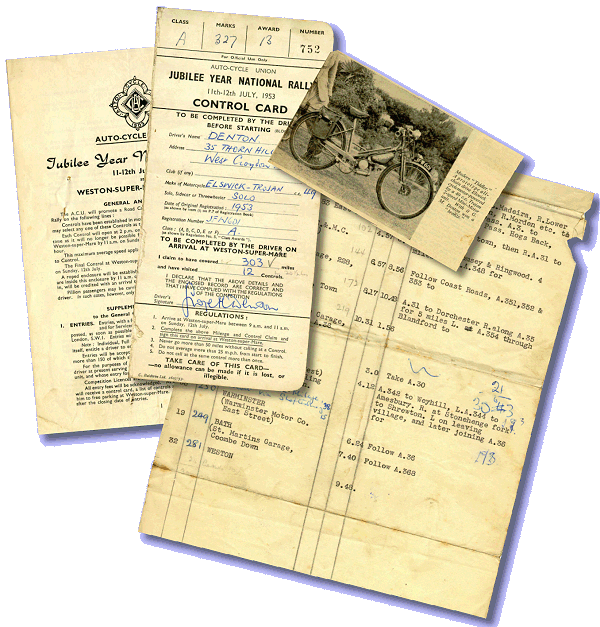

The Elswick–Trojan

[Photograph from the George Denton

archive]

Elswick–Hopper Cycles of Barton-upon-Humber ceased to be involved with powered two-wheelers long before the Second World War. After the war, in common with several other cycle manufacturers, they built a special strengthened bicycle for fitting a cyclemotor. Then, in 1953, the company was approached by the Trojan company of Croydon, to construct a frame for testing a new two-speed Piatti Mini-Motor moped engine they were considering for licensed manufacture. Although of the same period as the cyclemotor frame, the Elswick–Trojan was of completely different construction. When it was completed and assessed at Elswick, they were disappointed to find the gearbox particularly crude and clumsy in operation. The machine was duly handed back to Trojan and was subsequently ridden in the 1953 ACU 24-hour rally by Trojan Sales Manager Mr George Denton, to complete a creditable 303 miles and win a bronze medal.

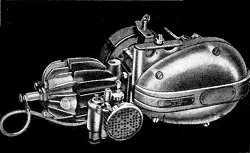

The Trojan 2-speed engine

Trojan’s promotional seed however, seemed to have fallen on stony ground since there appeared no takers for an option on the new engine. The licence was not taken up in the UK, though the two-speed Mini-Motor was adopted by a number of frame makers back in Italy.

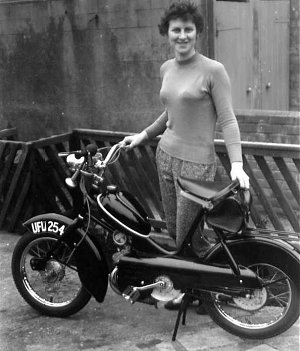

The Dunkley-powered test machine

Maybe this left Elswick with the idea about making their own moped, and assessments began later to select a suitable engine. The Mosquito cyclemotor was ruled out on the basis that the direct roller drive was too primitive. A Dunkley-engined Elswick test frame, number SCO1001, registered in July 1958, was running mileage on public roads, until it disgraced itself one day out at Skegness with a broken push-rod. Chief Engineer, Barry Wood was less than impressed at being stranded and left with no option but to drag the wretched machine home on the train—so that was the end of the Dunkley!

The star motor that emerged from the trials proved to be the VAP type 57, and it was this engine that formed the basis of the main test and development programme. In July 1959, six prototypes went for a week's testing at the Motor Industry Research Association (MIRA) proving ground. There were always ways round MIRA’s strict confidentiality rules, and the Elswick team learned that Hercules’s testing in the previous week had been prematurely curtailed after only two days, by frame failures on the dreaded corrugated pavé surface (it is presumed these machines would have been prototypes of the Corvette). Five of the Elswick–VAPs survived their ordeals, with only one machine being sidelined by a braze fracture of a fork brake anchor. In conclusion of a successful trial, several of the team testers reported obtaining ideal conditions speedo readings up to an amazing best of 50mph on tailwind runs around parts of the track!

All the prototypes were tested with rigid cycle forks, excepting Number 5, which initially was tried with an unsuccessful rubber block compression, leading link system. Later it was modified to a short leading telescopic arrangement, though this too was considered unsatisfactory for production purposes.

Elswick–VAP prototype number 5, frame number A1004

Fittings for the cycle assembly were selected by Mr Hopfinger, consultant to the project, and comprised an assortment of proprietary components. Full-width Prior alloy hubs were laced into Dunlop 15×2½" rims and shod with 20" carrier grade tyres, these being the same sizes as adopted on several scooters by Mercury and Dunkley. Though slimmer in section, the substantial, panel-sided mudguards appear similar to the Mercury Hermes, Dolphin and Dunkley Popular scooter types in their style of valance, and would undoubtedly have been very functional for their purpose.

Ida Wood, the wife of Chief Engineer Barry Wood, covered considerable mileage in road testing, and stands with one of the restyled VAP prototypes. UFU 254 carries the next consecutive registration to Number 5, so was undoubtedly one of the original MIRA test machines, and shows how styling for the Lynx was being developed. It wears the first engineering model trailing link fork set produced in the workshops, the first one-piece side-panels replacing the chain & belt guard set, and the characteristic rack that also carried over to the Lynx. At this stage it still wears the ‘bubble’ tank on the top frame tube and appears in the maroon colour that finished all the VAP prototypes.

The ‘bubble’ petrol tank with its tool cover was the same one as selected by Reynolds for its prototype mopeds, however, following-on from testing the Elswick prototypes, it was preferred to relocate a VAP ‘standard’ tank to underneath the seat for functional cleanliness reasons. Re-siting of the tank would have left the twin tube frame particularly bare and, in line with the vogue toward press-formed frames, it was decided to box the main section within two panel halves. Along with the new chain & belt guard side-panel sets, these were ‘tinsmithed’ out in the model shop, and no press tooling was ever made. The frame panel forms were styled to extend forward of the steering head, where they were ported to access the frame space as a cable tidy, and the forward joint was closed by a large, enamel painted, shaped metal badge.

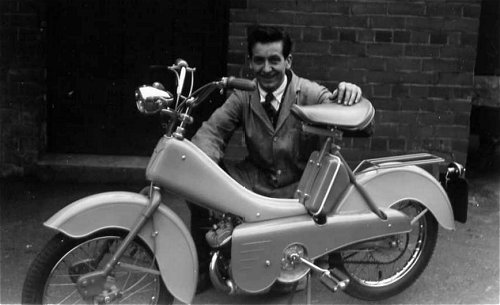

Barry Wood crouches behind one of the

two identical Lynx models prepared for Earls Court,

shortly before Harold Hunsley coach painted the finishing graphics.

The cycle parts were painted to a finish in two-tone blue, and graphics were skilfully sign-written by Harold Hunsley. Nowhere on the new styling models was the name of Elswick–Hopper to be seen—the machine had become … The Lynx!

The front forks were remodelled to a trailing link of the engineering team’s own design and manufacture, though there was a drafting error on the specification of the bottom link. When the 100 minimum batch of subcontract manufactured, machined, and chrome plated castings arrived back at the works, it was discovered the front suspension jammed as the spring link pivot was located in the wrong position! Oops! The Earls Court clock was ticking and time was running out to resolve the problem for the show, though it wasn’t really going to matter that the forks didn’t actually function, since the two show machines would only be required to ‘decorate’ the stand. The rule was always ‘dry tanks in the hall’ so there would be no need for the machines to even actually run.

Let’s leave our flashback for a moment, as standing before us many years on, is one of these very machines, somewhat deteriorated, a little incomplete, never registered and still never started! Now just press the ‘instant restoration’ button, and (eight months later) there we are—done! Ok, it’s had to have a few missing bits remade, like both side-panels, the exhaust, petrol cap, pedal chain tensioner, and rear sprocket. Then that front suspension geometry sorted out, the engine stripped and serviced, seat rebuilt, lots of general fettling (isn’t restoration easy in a few brief lines of text?) Finally, there's the MoT, age-related registration and we’re just about ready to take our brand new Lynx for its first ride!

With 20" wheels and a 44-tooth back sprocket, the Lynx works out at 6.7% higher geared than a conventional Auto-VAP on 23" wheels with a 54-tooth sprocket. This might be a contributory factor toward the reported ‘ideal conditions’ performance of the prototypes at MIRA, but surely not 50mph from a 1.75bhp motor driving a fixed ratio! When prototype Number 6 turned up in 2005, this became the only surviving example from the MIRA test still fitted with its original speedometer set, which proved to be a Smiths SN311/00 1770 anticlockwise 40mph model, so no claimed 50mph would appear to have come from this installed equipment.

The best guess here is that some test prototypes might have been fitted with other 60mph speedometers (possibly Huret or VDO), but had standard 23" speedo drives, so read 15% high. Allowing for this, our calculation brings the figure down to 42mph, possibly a somewhat more realistic expectation.

The Miller lighting fittings are driven from the VAP engine’s Magneclair electrical set. This is a particularly unusual device for the period in having no conventional round flywheel, so the plastic generator cover appears like a small rectangular box! The system features normal contact points with coil ignition, though in this case, its permanent magnetised poles remain static, and a small stator rotates within them! Following on with the inverse technology, flywheel effect is regained by the addition of a formed metal strip ringing the outside of the centrifugal clutch housing. Whatever the claimed capabilities of the unconventional Magneclair, in reality there barely seems enough power to dimly illuminate the 6V, 10W front & 5W rear bulbs. This wattage deficiency also carries over to the horn, which sounds less like a call of alarm, but more like a feeble cry for help from within the body panel.

The unscrew-on petrol tap is located through a port in the middle top of the left-hand side-panel, with access being a bit ‘snug’ so you won’t work it with your gloves on. Choke on the Gurtner D12mm carburettor is clicked on through another small finger-port at the front top of the right-hand panel; it clicks off as the throttle is opened. The wire gauze air filter butts closely up against the inside face of the right-hand panel, so a circular porthole allows the carburettor to breathe from the outside world. A trigger decompressor easily gets the motor spinning and stops it with a loud twittering noise when you’re done, so the general twist-&-go type operation is pretty conventional.

Following reconstruction and starting for the very first time on the stand, beside the bike and simply push down on one pedal; a cough on the first kick, then away and running on the second—not bad after over 40 years! Billowing clouds of smoke as you hold on the throttle to burn out the engine build oil, and tweak up the slide stop screw to find tick-over as the engine settles down. That little VAP motor sounds superb, and it’s easy to see why Elswick ended up selecting it. So smooth and fresh with a crisp popping note from the silencer, and so mechanically quiet compared to all the familiar noises that emanate from Mobylette Dimoby clutches. On which point, a surprise discovery comes when stopping our Lynx and trying to navigate it about the garage. It moves backward on freewheel, but doesn″t go forwards without turning the engine over. The reason for this is the drive to the motor is on a ratchet, and not a clutch like a Mobylette. This does go to explain why the Lynx pedal drive engagement mechanism is so easily changed by simply clicking a disc-switch in the middle of the flywheel, while the Mobylette has a wretched fiddly thing that jams and everyone is very loathe to mess with!

Initial take-off is best aided by some light pedal assistance as the single stage automatic clutch locks in quite readily and the high drive ratio works against it in this phase. Obviously not suited to take-offs on an incline! The motor, though, pulls quite steadily, and soon eases you up to a very pleasant cruising pace of 20–25mph, at which point it seems to encapsulate the whole feeling of the late ’50s and early ’60s Super-DeLuxe-a-Matic! Some vibrations start to creep through the machine above this speed, becoming noticeable in the buzzing of the various body panels and through the Tarantula rubber saddle, so the general tendency is not to run the bike much quicker for very long. The motor itself runs smoothly and cleanly while pulling under throttle, but readily breaks into four-stroking on light load, though the effect is quite muffled and not disturbing. The ‘open ported’ carburettor surprises with its unobtrusive intake draw, so the laminated wire gauze filter proves fairly effective in damping out the sound.

The cycle frame is a rigid rear, and you’d think the front end was as well! Despite their technical appearance, those undeveloped trailing link forks prove to be way over-sprung and the links generally remain firmly against the down-stop buffers. The steering is also quite light, and there's a tendency for the machine to wander somewhat, which requires the rider to compensate by a little more concentration to pilot a straight course. Cornering under power at speed is very confident thanks to the 4-ply × 2½" wide tyres, much firmer than any comparable moped, and more like a light motor cycle. While the excellent full-width Prior alloy hubs deliver the expected braking performance, the effect is completely ruined by the behaviour of those forks! Under front braking they nosedive, to kick back hard against the stops again as the machine slows or the brake is released. The same effect also occurs every time one hits larger bumps or potholes, and you very quickly wish the bike had some other arrangement. The other reaction when spring compression takes the links off the down-stops is that change in state suddenly makes the fork-set feel rather unstable. There’s no damping system in this action either, so the whole front suspension function becomes a fairly disconcerting experience for the rider. It takes quite a bit of getting used to, and never feels particularly right. It’s unlikely that Elswick’s testers would have recommended the system for production—that’s if they’d had the opportunity to try it!

Thrashed mercilessly, crouched, on long downhill stretches, top speed achieved was 36–37mph, confirmed by a pace machine. At that speed, the engine was revving smoothly and confidently (having gone through the vibration band); so that completely explodes the myth on the speed capability.

Visually unusual, though a striking looker, the Lynx would probably be comparable with the contemporary belt and chain drive Raleigh RM4, Hercules Corvette, VAPs and basic Mobylettes—but how would it fare in the market place against the competition?

A Lynx on the Scootamatic stand

at the 1960 Earls Court Show

The two show models really did grace the hallowed halls of Earls Court in November 1960, on Stand 83, though they were merely listed among ‘Auto-VAP, Capri, Como, Honda, Laverda, Lynx, Velo-VAP’. No launch announcement, no press release—just a couple of cats in the crowd, and probably few people even noticed they were there. It was almost as if there was no real interest in actually selling the Lynx, so what had happened?

Stand 83 didn’t even represent the Barton works, but bore the name of Scootamatic Ltd with a London office, Sales & Service Headquarters in Nottingham, and seven regional service centres (interestingly, one of these was located at National Works, Hounslow, the former Dunkley site). Formed by the management of Elswick–Hopper, Scootamatic was a new company specially set up to handle sales of the above listed imported mopeds and scooters (though they actually declined the Honda, thinking it wouldn’t sell—a bit like Decca Records failing to sign The Beatles!) Having finally estimated the Lynx at a manufactured cost of £58, it was coming out significantly more than the purchase cost of factoring a comparative Auto-VAP (the Caravelle model was actually being listed for £56 13s 0d at this time), so it looked like the obvious decision had already been made. In terms of wider practicalities, the two Lynxes were no more than display models and no capable tooling existed to actually make them. Scootamatic was hardly in a position to accept any orders for them at the show!

Despite this, the ‘Scootamatic Lynx’ appeared in the December 1960 Market Guide of Power and Pedal, listed at £63 0s 0d.

Though it was planned to run the two frame side covers and both side-panels on Elswick’s 90 ton press, in reality it would have been difficult to see Elswick finding the financial justification required for the considerable outlay to cover the cost of the full tooling suite. Besides which, the model panel forms were still not even developed for practical production manufacture! Maybe, if Elswick had decided to go with the basic, original prototype format a bit earlier, then things could have been different. The rigid cycle forks and simple fittings would have been much more economic, well within the general manufacturing capability, and without the crippling tooling outlay.

The Elswick–Hopper moped’s evolution into the Lynx had developed beyond practicality, and in the cold light of day, there was little real chance of the machine ever reaching production; nevertheless, the two models stood for a while longer as ornaments in the company foyer.

Despite assembling VAPs (which were serialised as a continuation of the Elswick frame numbers) and Capri scooters at St Mary’s Works, Barton, the factored profits at Scootamatic contributed little to Elswick–Hopper, and this work came to an end in 1966.

By 1968, Coventry Eagle’s Birmingham site at Smethwick was up for redevelopment, and it was decided to relocate to Barton-on-Humber where they took a lease on some of the old Elswick buildings that were no longer required by Hopper. Falcon racing bikes progressively developed as the dominant brand after Ernie Clements had bought out the Coventry Eagle Company, and moved the business inland from the Humber, to the old Corah factory at Brigg in 1973, now calling it Falcon Cycles. Cash flow pressures in 1978 resulted in Falcon being purchased by Elswick–Hopper; they continued making both brands and acquired others. The cycle business was sold off to Casket in the late 1980s, and finally to Tandem Group plc, as it remains today–the UK’s largest cycle manufacturer. Reading down the listed Tandem brands are: Falcon Cycles, F Hopper & Co, Elswick Cycles, Coventry Eagle, Wearwell Cycle Company, British Eagle, Townsend, Optima, Shogun, Holdsworth and Claud Butler.

Elswick plc continued beyond the cycle trade as a print and packaging business in self-adhesive and garment labels, before disappearing within a larger group takeover in 1994.

Tracing the records in Lincolnshire Archives (Lincolnshire CC issued all the Elswick registrations) doesn’t reveal many more secrets. The Elswick–Trojan shows in the registration records as a ‘Mini Motor Bicycle’ on 19th January 1953 with engine number CBC1102, its last licence expired on 30th April 1963 under registered keeper Miss V Snowden, 60 Serlby Lane, Harthill, Sheffield.

The latest piece of the jigsaw: MIRA test prototype number 6

with frame number A1006, surprisingly turned up in 2005

(restoration is ongoing), and was re-issued serial UFU 256

as a machine of historical importance.

Of the Elswick–VAP prototypes, four serials are recorded in a block as UFU 253 to UFU 256, issued on 26th August 1959. However, the registration cards are blank so details of the frame numbers were not entered at the time.

The card for the other surviving Lynx, frame number A1005, registered 27th May 1968 is also blank of machine details, however the log does record that the registering agent at this time was actually the Elswick Works. As the old Elswick factory site was progressively cleared, local enthusiasts managed to rescue the two historic Lynxes, thankfully both survive. A1005 was used locally for a few years, before being restored and preserved, still in its hometown of Barton.

The Elswick–Dunkley picture was taken in the post works ownership of Chris Welch who rode it in 1963 & 1964. Its last licence expired on 31st March 1965 under the ownership of Roger Keal of Barton, who reportedly disposed of it in a rubbish bin when the engine packed up!

Finally in 2002, after 42 years, the second Lynx, frame number A1014, completed restoration and took to the highway—a little piece of history now out on the autocycle rally circuit.

The old factory buildings still stand, chiefly occupied by Meldan petrochemical industrial fabricators. The 1911 assembly shop currently sees little use under M&M Picture Frame Mouldings Ltd; Coles Engineering occupies a small machining workshop at the site off Marsh Lane, while the Soutergate entrance is home to general engineers W M Codd, and Beck Hill Motors garage.

During research into production of the Lynx article quite a file of other unpublished research material was recorded into the archives of IceniCAM, including further references on the Elswick–Trojan, the Elswick–Dunkley, and photographs of all the Elswick–VAP prototypes at the MIRA test track and Barton Works. Copies of this material are available upon application to IceniCAM Information Service.

Some of the archive material about the Elswick–Trojan

[Text & photos © M Daniels. Period documents and pictures from IceniCAM Information Service.

It was back in 2003 that we published the first article about the Lynx. Over twenty years later, we exhibited the Lynx on the EACC″s club stand at the 2024 East Anglian Copdock Bike Show. Some large-scale copies of the photos featuring Rhoda and the Lynx were made for the occasion. What we weren’t expecting was that Rhoda would be visiting the show; she, in turn, was somewhat surprised to be confronted by large pictures of herself on the wall! To mark the occasion, Rhoda posed for a photo in front of the earlier pictures.