We pick up each of the chapters of each tale heading into World War 2, to set the stage for our Band of Three cyclemotors, which would all appear shortly after the war.

Our Band of Three cyclemotors

In the 1930s, the Bianchi Company began building trucks for supply to the Italian army to satisfy Benito Mussolini’s empiric ambitions in East Africa and the Balkans. Supply of military vehicles consequently found the famous bicycle and motor cycle manufacturer entered onto the target list in World War 2, and production ended dramatically during the allied bombings of August 1943, when the Bianchi motor works, its truck factories, and warehouse buildings in the triangle zone between Viale Abruzzi, Via Plinio, and Via Pascoli of Milan were practically all destroyed. Because the whole factory had been so extensively damaged, Bianchi was faced with the prospect of having to completely rebuild, but the future of the company was then hit by a second tragedy on 3 July 1946, when its founder Edoardo Bianchi died at 81, and control of the firm passed to Edoardo’s son Giuseppe.

By 1950 the bombed out Bianchi plant was rebuilt, modernized, and initially returned to production making bicycles again. The new works occupied the same triangular site along Viale Abruzzi, with its office building on the corner to Via Plinio, just opposite the Basso bar, while the cycle racing department was in Piazza Ascoli.

Bianchi’s post-war return to motorised vehicles in 1950 focussed on selling economic commuter machines for a transport-starved Italian domestic market. This began with a basic 125cc Bianchina motor cycle, and that great budget mainstay of those austere post-war times, a roller-drive motorised cycle which Bianchi sold as a complete machine, and called the Aquilotto.

The early Aquilotto engine was 45cc and fitted with a 9mm carburettor. The first models had 26-inch wheels, and were finished all in black with a chrome tank and a central wing of cream; then they moved to a black frame with optionally coloured fittings, but retained the chromed tank with the cream wing centre.

The 45cc engine was also offered as a cheaper Aquilmotor clip-on attachment kit, so customers could motorise their own bicycle.

A ‘Sport’ version of the Aquilotto soon followed, with a 12mm carburetter to make it slightly faster. Later ones fitted a different style of tank to the initial model, which could be either two-tone finished or chrome plated. From 1954 came the Aquilotto Oropa models, where the displacement remained at 45cc, but having a two-speed gear and clutch with chain final drive; also the Azalea model of 45cc with a curved top-tube frame and direct roller-drive transmission. A new Rapallo model introduced a smaller and lighter frame without seat stays, 24-inch wheels, and the engine size increased to 48cc (47.8cc). Next came the Amalfi, where the wheel size returned to 26-inch, but fitted with the new capacity 48cc engine. Rapallo and Amalfi models were direct roller-drive, while the Amalfi and Oropa models shared the same larger style of frame.

The final Aquilotto version, sometimes called the Avanti, was a small-wheel folding moped.

The various Aquilotto models proved more popular than the Aquilmotor as most customers generally favoured purchasing a complete machine, though the clip-on cyclemotor kit also continued with the 48cc engine unit.

Since the roller-drive Aquilmotor attachment engine could be fitted to any bicycle, they’re more usually found on all sorts of different cycle makes, and are much less frequently mounted on a Bianchi bicycle, because customers would generally just purchase a complete Aquilotto model instead. The complete machines were more popular in Italy where, unlike the UK, there was no tax advantage in buying the engine and cycle separately.

Il Buono

This Eduardo Bianchi cycle, coded by frame number B.367528S, is a fabulous example, with a Gent’s crossbar 22½" frame standing on 28" wheels with 1⅜" tyres, so it’s a long way up to the saddle—err, anyone got a stepladder?

There’s a round fuel tank transversely mounted below the back of the saddle and built on to the rear carrier. Both rod brake linkages run elegantly though the inside of the handlebars, with the front link emerging cleanly beneath the bars in the middle and ahead of the stem, then continuing slickly down to operate the conventional front stirrup calliper. The rear rod exits the handlebar just left of the stem, to connect to a typical pivot at the bottom of the head. The linkage then follows that unusual top-quality Italian V-link configuration from the bottom bracket, back up the saddle tube, to work the calliper beneath, at the top of the stay. While you’d generally expect to see this calliper location as the norm from later cable operated brakes, it’s quite unusual for earlier rod operated cycle brake systems, and places the brake mechanism at a higher position more out of the elements. This requires a little more engineering to manufacture, and is generally only found on the better quality Italian cycle frames … and there’s no doubt that our Bianchi meets that standard!

Specifications of our Bianchi Aquilmotor No 39737 give 39mm bore × 40mm stroke for 47.8cc with 6:1 compression ratio, and rated at 1.5bhp @ 6,000rpm, with a Dell’orto T1-12-DA 12mm carburettor, and quoted speed of 35km/h (22mph).

The Dell’orto T1-12-DA carburettor features the usual confusing choke control marked Avv.to→ / ←Marcia, which is pretty unclear to many people, but translation misinterprets Marcia as ‘confine’, so we read this as choke position for starting … except the motor isn’t interested at all, until you switch to Avv.to, and then it starts!

There’s a dual control lever set on the right hand bar, working decompressor and throttle. Engagement lever down for drive, decompress on the trigger, pedal away to get the engine turning, then release the decompressor … and the motor readily fires.

The unsporting form of the handlebars didn’t readily lend themselves to adopting much of a crouch position (not that a crouch offered any discernable performance advantage anyway—we did try). Along the flat our Bianchi normally paced at 21mph, but on a light downhill run or catching a following wind in the sails, could be teased up to 24mph, but immediately drops the extra speed again once the bike levels out back on the flat.

The cycle lamps are powered by a Radius friction drive dynamo running on the front tyre: simple and adequate for the performance.

Born on 27th April 1897 in Stradella, Italy, Pietro Trespidi completed his studies at an industrial institute, then moved to Milan, where he was employed in Giuseppe Gilera’s workshop. In the early 1920s he returned to Stradella to set up his own workshop, where he repaired vehicles and, in his spare time, set about designing and building his own motor cycle with a 250cc two-stroke engine. Completed in 1924, Pietro’s motor cycle was tested and favourably reviewed in an article of April 1925 by the specialised Motociclismo magazine. The feature particularly praised the technical qualities of Trespidi’s motor cycle, which brought it to the attention of the townsfolk of Stradella. Given the modest economic situation of their ingenious fellow citizen, a group of people clubbed together to raise popular subscriptions of 100-Lira shares to establish the Società Anonima Moto Trespidi, which was subsequently founded on 10 February 1926, and described by Motociclismo as a ‘small factory with modern equipment, capable of producing at least six motor cycles per month’.

The business received some promotion when a 250cc ‘Sport’ ridden by Ignatius Pernetta won the Italian championship, and a ‘Turismo’ version was also introduced. After having built some 100 of the 250cc motor cycles in ‘Turismo’ and ‘Sport’ versions, increasing demand for the machines promoted a re-foundation of the company in 1927, raising further capital to expand production capacity.

In 1929 a 175cc light motor cycle was added to the range, but as the Great Depression began to take effect, the business experienced a dramatic fall in orders, managed to survive through 1933, but had to close in the early months of 1934.

Trespidi returned to his old mechanical workshop, and resumed his engine designs in the hope of being able to start new production activity in better times to come … but all that came was World War 2. Although Italy had surrendered and signed an armistice with the allies on 3 September 1943, which was publicly declared on the 8 September, the northern part of the country remained under the control of Nazi forces, who fought on until their final surrender at Caserta on 29 April 1945.

During 1944, with the Pavia area still occupied by the German military, Trespidi designed and built an ‘auxiliary micromotor’ prototype intended as an attachment engine to motorise a bicycle. During ongoing conflict within the region, with the support of some friends, he founded the Motobici company on 24 February 1945 to start production of the clip-on motor, which Pietro Trespidi named ‘Alpino’ … all while the Allied forces were still preparing for their Spring offensive of 9 April – 2 May 1945. That was quite an example of confident optimism!

The new Motobici Stradella (Pavia) Company became one of the first Italian cyclemotor manufacturers; it had already started production in small series of the chain driven ‘Laterale’ Alpino S48 during 1945, which was given a range of 70km on a litre of fuel and a speed of 40km/h. At the end of the Second World War, production quickly stepped up as demand for the Alpino increased, thanks to its already established reputation of being a well performing engine that proved virtually indestructible.

1946 brought in the ‘Laterale’ Alpino S3 version, 1947 the ‘Laterale’ Alpino ST60 63cc ‘Carrier’ motor, and Piuma (Feather) model.

1948 introduced a 98cc motor cycle and a new type of rear-wheel, roller-drive, micromotor R48 attachment engine, while revisions of the earlier ‘Laterale’ chain-drive designs also still continued from 1949 as the C48, and CF48 of 1950.

The final of the 1948 Campionato Triveneto in Padova

Alpino riders Vincerà Pinardi (5) and Paolo Perotti (6) pull away from the

starting line;

most of the other riders are on Ducati Cucciolos.

1950 represented a year of change as production began to shift significantly from cyclemotor engines to favour new 75cc and 125cc motor cycles, and a 98cc Marinella scooter.

Following disagreements with the shareholders in 1950, Pietro Trespidi abandoned Motobici Alpino to found another company in 1951, again in Stradella, as SIMES (Società Industriale MEccanica Stradella), which launched under the Ardito brand with a model 49B auxiliary motor, and two-speed transmission. Using the same engine, Ardito built the Bicimotore 48 in various versions including a De Luxe model.

SIMES then marketed a model with 73cc engine, three-speed gearbox and dry clutch, with cycle components sourced from different proprietary manufacturers, and followed with an Ardito 75M Motoleggera, further two-stroke ‘sport’ light motor cycles of 100 and 125cc, and a 175cc four-stroke. Competition laurels for Ardito machines ridden by Paolo Perotti gave a welcome promotion for the brand.

Meanwhile, back at Motobici Alpino, production continued with the addition of an F75 scooter in 1951.

An extended range of 125cc motor cycle models was announced in 1952.

In 1953 the Ardito catalogue listed a Scooterino 49, Lusso 49 scooter, but although the business had got off to a promising start, it had entered the market at the beginning of a difficult time, since interest was already drifting away from two-wheelers toward cars. SIMES Ardito was very quickly compromised by a general decline of sales in the motor cycle trade, and increasing effects of the resultant competition for business, which immediately put the company into serious difficulties and forced it to close in 1954.

Il Brutto

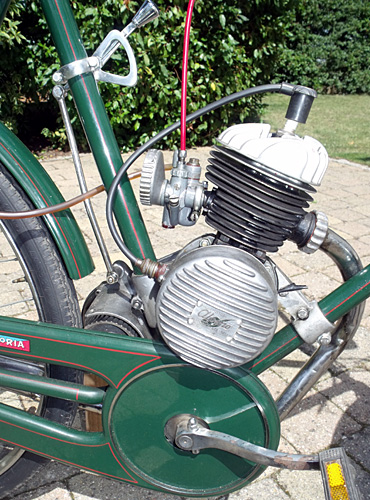

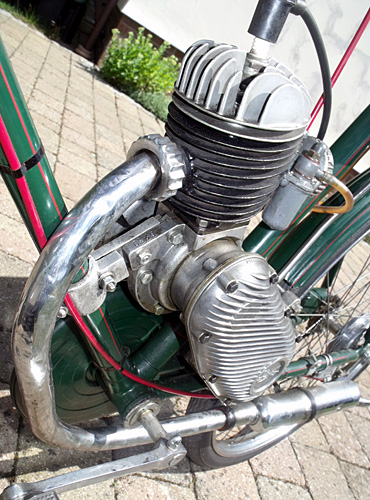

Our Alpino R48 clip-on engine number 6239, which we think dates from around 1953, comes fitted in an AMF Gloria 23" crossbar gent’s cycle frame number 75303 dressed in an extravagant green and red finish, which makes a pretty impressive combination!

During World War 2, the Bianchi factory and its warehouse buildings in the triangular zone between Viale Abruzzi, Via Plinio and Via Pascoli were practically all destroyed during the allied bombings of August 1943, but just a little further along Viale Abruzzi, the Gloria site came through much more fortunately, and was barely damaged at all.

Since the Gloria factory remained practically unscathed, it was well placed to benefit from a quick return to production, while many of its former cycle trade competitors were in a much less fortunate position, and work in the Gloria factory at Viale Abruzzi 42 markedly increased as the bicycle became the most common means of transport in the impoverished immediate post-war period.

Around 1950, AMF Gloria was producing around 25,000 bicycles a year of all types: men’s, women’s and even children’s cycles, while an impressive display along the now ten ‘showcase’ windows around its showroom’s corner of Corso Buenos Aires to Via Scarlatti now also included its various new cyclemotors and mopeds. In 1948, Gloria had developed its first bicimotore (motorised cycle), with a roller-drive engine of 40cc that could be fitted into its own cycle frame and sold as a complete machine.

This was succeeded the following year by an improved bicimotore model, having its two-stroke engine and horizontal cylinder capacity raised to 48cc by increasing the bore size from 35mm to 38mm, and now rated at 1.1bhp. Late in 1949, the cyclemotor was joined by a band-sprung-frame moped, ready for the 1950 season. This used the same 48cc motor top-end as the cyclemotor on a hand change three-speed engine unit, with chain final transmission, and was presented at the Triennale di Milano by Gloria’s founder Alfredo Focesi.

In the early 1950s, Gloria was considered to be among the elite of Italian bicycle makes, and its finer road and racing models, marked La Garibaldina, were subject to the highest standard of finishing at the frame joints. These were finely fettled by careful hand filing, which took the craftsman three to four hours, compared to standard market models that were normally finished in just half an hour of work.

Gloria’s quality products were still mainly focussed toward the upper end of the market, at a time when, despite a greater affluence beginning to emerge, there was generally insufficient money available for excessive indulgence … but Alfredo Focesi, was gambling on an economic boom.

The three-speed moped was quickly developed to become the Gloria 3/m in 1952, with pressed steel frame, telescopic forks and swinging-arm rear suspension. This remarkable machine was probably the earliest recognisable ancestor of the ‘sports moped’, though performance limitations from its heavy cast iron piston and the 1.1bhp power output from the engine wouldn’t have been particularly athletic. The design however was amazingly advanced considering that many other manufacturers were only just beginning to build clip-on motorised bicycles!

In 1953, the range grew with the addition of the Glory-100 motor cycle, a 100cc overhead-valve single with a pressed-steel frame; and another 125cc model with a four-speed transmission, which was further available in Touring and Sport versions. In 1954 the business converted to a joint-stock company under the name of Commerciale Gloria SpA, ambitiously to raise capital for further investment and expansion. For the 1954 exhibition in Milan, Focesi introduced a further new 160cc four-stroke engined motor cycle, with swing arm rear suspension and an Earles pattern front fork.

The choices linked to the expansion of the business, however, failed to return its investments in time, because of insufficient sales, and on 21st February 1955, the Milan court declared the AMF Gloria business bankrupt, and production ceased in 1955.

The Alpino clip-on engine would have been a very period marriage with the Gloria frame, and it really looks the business! The finned reduction drive casing looks fantastic, and is obviously going to promise better drive roller traction by enabling the mechanics of a larger diameter drive roller, and going to improve its capability greatly in wet conditions.

The high performance and indestructible reputation of the R48 cyclemotor is matched by the fitment of Wipperman ‘Ultra rapid’ 12mm half-width alloy brake hubs laced into 26×1½×1⅝ rims with 650B tyres. This is an extraordinary cyclemotor that exudes a magical promise of performance, quality, and extravagance … we just have to get it going first …

Usual preliminary checks: no spark, but as we spin the engine, straight away, those main bearings don’t sound too good. Pressing on, clean the points, fit a non-resistor cap, and new plug … yes, we now have spark. Drain the tank of the stale old fuel … hmm, smells really nasty, perhaps we’d better clean out the carb too … so take off the carb … but you can’t? Nope, there’s not enough space to withdraw the carb body off the inlet manifold before it fouls the saddle tube!

What? Do you really have to take the engine out to remove the carb? Yes, I’m afraid you do.

OK, we’ll settle for twisting the carb body over on the manifold, then taking off the float chamber top and the main jet, flushing it out in situ, and blowing everything out with an air line.

Fresh fuel, and let’s give it a try.

Oh great, the Alpino engine doesn’t have a decompressor! So we’re going to be pedalling an unknown cyclemotor up and down the road, against compression, to try and get it to start—I don’t think so. So it’s out with the electric starter: a mains drill on the mag nut! After a drop of encouraging fuel through the plug hole and a bit of effort free cranking, we manage to get the motor fired up (and the rumbling main bearings certainly don’t sound any better now the engine is actually running), so run to warm … and hope it might go again when we try it again for road test.

OK, without any decompressor, the procedure is to notch down the drive lever on the left of the saddle stem, which tilts the engine to bring the drive roller into engagement with the tyre. There are five notches on the latching quadrant, from disengaged, to increments of engagement pressure to optimise drive without roller slip according to conditions. A lighter engagement setting in dry conditions can reduce transmission drag for increased performance and fuel economy, but a higher pressure may be required when the load increases against inclines, or under wet conditions when the roller may slip.

Back the engine onto compression, then raise the lever back up to disengage the drive, so you can pedal the bike up to speed before re-engaging the drive and spin the motor over.

Our efforts to pre-run the motor and restart while the engine is still warm seem to pay off, as the motor starts right away.

Our text might make this starting operation seem simple and straightforward, but its most certainly not!

Operating the drive lever requires reaching down the frame with your left hand, with only your right hand to steady the handlebars and work the throttle lever—all while you’re still pedalling against the compression!

To make matters worse, the carburettor has no choke or strangler to assist starting. It just has a flood button, so that’s going to be a little random.

Imagine a cold start on a frosty December Monday morning in Barrow-on-Humber, already late for the first shift at Elswick-Hopper Cycles’ Barton factory for the 7am morning shift, and you’re faced with a cold, damp start on your fancy Mediterranean cyclemotor … which has no idea that temperatures below 45ºF even exist!

Yeah, that’s a really long way from our warm re-start.

Anyway, we’re up and running with our pacer peeling in behind to track our progress, so tease open the throttle lever to see how the Alpino motor responds, and it’s very impressive! The torque is remarkable for an early 1950s’ cyclemotor, this is easily the strongest clip-on motor we’ve ever ridden … loads of power … is this really 50cc? You could easily believe it’s 70 or 80cc!

Even our pacer is taken by surprise as we smartly zip the Gloria–Alpino away from our shadow, so James throttles on to catch back up by the junction, but we’re away first, and already tearing up the road.

Happy that our Alpino is up to performing temperature, we’re giving it the beans, and revelling in the excellent acceleration with James in chase—then, aargh! Tank-slapper! What? Hitting a violent tank-slapper in the mid 20s is something that nobody could ever expect, and on a flimsy cyclemotor, it’s nearly as scary as it is on a Model-100 Panther at 60mph because the frame has broken on one side of the swingarm, and is chucking itself across both lanes of a dual carriageway.

When you get into a tank-slapper, the only way to handle it is gently ease back the throttle, and try all you can to keep the bike on the road until the oscillations abate, and those eight seconds seem to last for eight minutes.

600cc Panther or 50cc Gloria–Alpino, getting in a tank-slapper at any speed is a pretty scary moment.

James in the meantime has braked back to a clear distance just in case we can’t control it, and once the moment is passed we return slowly back to the workshops to check for any faults, like a rear wheel nut loose on one side maybe … but following a careful inspection, we fail to find any obvious cause.

So after pumping up the tyres nice and hard, and taking our brave pills, we try for another run.

Cautiously tweaking open the throttle lever, and firmly holding on to the handlebars, we gingerly push the bike up past the mid twenties. James is pacing from a noticeably more respectful distance this time as we push into the high 20s—maybe pumping up the tyres has made the difference—meanwhile our pacer is clock watching to see if we can get past the 30mph barrier. Alpino powers the Gloria strongly forward as a possible contender for our cyclemotor land speed record, and while the performance of the engine certainly feels like it could power to the moon, Gloria suddenly decides to chicken out of the celestial opportunity for greatness at 29mph, and throws us into another tank-slapper.

Because we were braced for the very real possibility of another tantrum from Gloria, we held on and checked back the throttle as soon as the twist & shake started again, and once Gloria had finished her moment in the limelight—that’s enough of that game, we’re going home.

Our Alpino–Gloria seems to be just too fast for its own good.

It really felt as if the Alpino engine could have eclipsed even the Teagle’s 31mph record for 1950s’ cyclemotors, but not on Gloria, and not today.

The great looking Wipperman hub brakes … didn’t work anything like as well as they looked; they were useless, and having lost any further interest in riding Gloria again, we later realised we’d never even tried the lights.

The difficulties associated with operating a fiery cyclemotor like the Alpino with no decompressor, create a lot of complications in its use. The awkward to locate and operate engagement lever means taking your left hand off the bars at time when it’s hardest to control the bike as it’s usually about to stall out. Every time you stall to a stop, it makes re-starting really hard work. If you’re in town traffic, you’re going to be seriously thinking about buying a different cyclemotor.

Our third chapter again picks up the story during World War 2, during which time the Turin lawyer Corrado Corradi was operating a small business producing and selling car parts and accessories. In 1944 he started supplying clip-on engines for mounting over the front wheel of a bicycle, which were believed to be 49.5cc two-stroke OMB Tauma auxiliary motors made by Officine Meccaniche Benesi of Turin.

In 1947 Corradi also sold further 58cc two-stroke Benotto OMB Sirio ciclomotori kits, which attached at the left-side rear wheel spindle.

Corrado subsequently decided to start making his own engines, and founded his own company Industria Torinese Meccanica Srl. in 1948 at Via Francesco Millio, employing former aircraft pilot from Sicily, Guiseppe Spotto, as a young engineer, and assisted by colleague Silvano Bonetto to begin designs of new auxiliary bicycle engine kits.

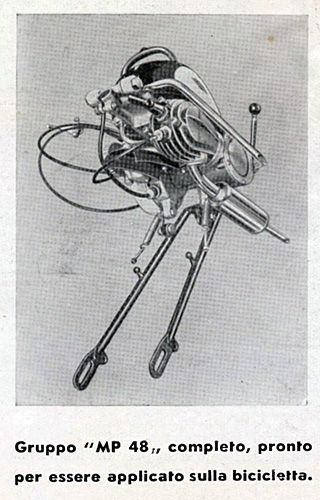

The first clip-on 48cc two-stroke engine FM version was mounted above and driving the front wheel, and was sold under the simplified brand name of: Itom.

A second MP version of the same motor was developed to mount behind the cycle saddle and driving above the rear wheel, then finally a more popular third variation placed between the pedals and driving the rear wheel from beneath the bottom bracket, which became quite famously known as the ‘Tourist’ model.

In 1950 Itom produced its first complete Motorette Alba 48 TR cyclemotor with a tubular frame and automatic clutch, which was shortly followed by a two-speed motor version.

The front and rear mounted MP48 Itom cyclemotors were imported to Britain in 1951, and were marketed by Adimar of 222 Brixton Road, London SW9, then both were replaced by the Tourist model in 1953.

Well that was brief, because here we are already at our third Italian cyclemotor.

Il Cattivo

Seemingly based on a Henry Ford Model-T paint scheme, it’s all black, and if viewing the bike from the right-hand side, a casual glance could easily take the machine to be no more than an old-fashioned bicycle.

The black front and rear mudguards are both fitted with spray valances, and you’d barely spot the low-slung Itom engine tucked behind that big black fully-enclosed chain-case, and that matching black camouflaged fuel tank mounted on the down tube blends right in with the general blackness, so your casual observer probably wouldn’t register that either.

The flat-bottomed fuel tank comes as part of the ‘Tourist’ kit, and simply bolts at an angle onto the cycle frame down-tube by a couple of U-brackets. It looks more like it should be mounted on the top crossbar tube in sports motor cycle style, but maybe the width of the back of the tank might obstruct the pedalling arcs? Maybe it wouldn’t drain its fuel so effectively, and maybe the longer fuel line routing could be prone to being caught? All illustrations demonstrate the tank mounted on the front down tube, but it really doesn’t look quite right from some side angles or the front.

We’ve been unable to identify the make of the cycle frame, but there’s no doubting its quality from the rod brake linkages both running tidily through the inside of the handlebars. The front linkage neatly emerges beneath the bars in the middle and ahead of the stem, then continues down to operate the conventional stirrup calliper. The rear rod exits the handlebar just left of the stem to connect to a typical pivot at the bottom of the head, with a rod to the bottom bracket and another pivot, then a V-linkage back up the saddle tube to connect to the calliper at the top of the rear stay.

Look around the cycle frame, and the rear lamp built into a fitted cycle lock is a novel touch.

The ‘Tourist’ two-stroke motor with iron cylinder, alloy piston and cylinder head is given as 39mm bore × 40mm stroke for 48cc, and rated 0.7bhp at a lowly 3,000rpm, though could be claimed to produce up to 1.4bhp at obviously higher revs.

The double-sided decompressor–throttle control lever clamped on the right handlebar is a neat twin control, but not for this bike, because the bosses that clamp it to the handlebar completely block the front brake lever from operating! It’s not anything you can fix either, because no matter how much you try turning the control up or down the handlebar, or rotating the control on the bar, it still fouls in every position—except if you move it in towards the centre of the handlebar, but this inconveniently places the throttle control well out of reach, so you’d have to take your hand from the grip.

Apart from being highly impractical, it doesn’t exactly help anyway, because we find the front brake lever very firmly sticks on whenever you pull it in. You have to physically push the brake lever off again to get it to disengage, so it’s no use either way–OK, we’ve effectively got no front brake.

Looking down at the left-hand side of the motor, there’s an interesting foot operated engagement pedal with a Gilera rubber on the peg? No, that’s original Itom equipment supplied with the Tourist kit, and it’s just a Gilera kickstart rubber. Push the lever down to engage the drive, toe it up again to release, so you can use it like a clutch.

Another piece of the Itom kit is the special dogleg left-hand pedal crank arm, which is essential to clear the protruding magneto casing.

The carburettor is the same Dell’orto T1-10-SA as fitted to the Alpino, but Itom equipped their carb with the more usual filter and confusing choke control marked Avv.to→ / ←Marcia, but we’ve been here so many times before that we now know that Marcia = running, and Avv.to + Avviamento = starting.

When it comes to starting the Itom, turn on the fuel tap, and switch the choke control to Avv.to. Because of the foot operated engagement lever we don’t need to lock in the drive before we set off, so we may not need to use the decompressor to get the motor started. You can simply pedal away, stomp down the lever to engage the drive, and maybe the motor will fire up—but this won’t exactly be a flying start because the choke is on, and the motor will soon start coughing. There are now two options: stop and reach down to turn the choke off by hand, or tip the choke lever with your left foot and nudge it across to Marcia. This can work to a degree, but in the long term it’s maybe not the best idea to be putting the boot into your carb with a pair of hobnail beetle crushers.

The Itom exhaust is a tinny and un-baffled can, which emits a low flat drone, rising in pitch as the revs build up. People are definitely going to hear this coming, and going, but the noise will always be with the rider. Smooth running can be compromised by some bouts of four-stroking bluster particularly when the engine is cool and off-load, though these tend to abate as the motor gets hot and is pulling under load.

Our first runs were performed in wet conditions and plagued by roller slip, which was probably not helped by the low under bottom bracket mounting position presenting the transmission directly in the elements. Even re-adjusting the engagement to higher pressure failed to clear the slipping problem, because the roller is a relatively small diameter as a result of the simple direct-drive design. Other indirect drive cyclemotors with internal reduction gearing would hold an advantage under the same conditions, since they can run a larger diameter roller for better traction. 20mph proved the best performance available under these wet conditions, because the drive roller always slipped on the tyre once the throttle was fully opened. Once conditions had dried, our third run seemed better as full throttle could now be applied without roller slip, but with the drive engagement still set to maximum pressure, the best achieved speed seemed limited to 22mph on flat due to four-stroking bluster. As we cruised around our course to see if the motor might improve as it got hotter, it actually seemed to do the opposite, with some intermittent firing, which felt like a developing ignition fault … so back to base again for further investigations.

With the dirty contacts now properly refaced, and the engagement pressure adjusted back to suit dry conditions, our Itom now accelerated rather better, and seemed to cruise comfortably and consistently at speeds up to 22mph, managing to pace up to 24mph along the flat in a couple of sections, and further mercilessly thrashed up to 26/27mph in downhill sections, but still the four-stroking combustion issues prevented the engine from cleanly running at higher revs. Performance in the dry proved better once we’d got the bike sorted out, but the Tourist was certainly very restricted in its wet capabilities.

The Itom Tourist cyclemotor remained on sale in the UK until 1961, listed at £28–10s, which surprisingly was still the original posted price when it was first introduced to the UK in 1953!