Turin lawyer Corrado Corradi founded his Industria Torinese Meccanica Srl. in 1948 at Via Francesco Millio, to begin production of auxiliary bicycle engine kits that were designed by Guiseppe Spotto, a young engineer from Sicily who had been a pilot in the Second World War, and his colleague Silvano Bonetto.

The first clip-on engine version was mounted above and driving the front wheel, and was sold under the simplified brand name of: Itom.

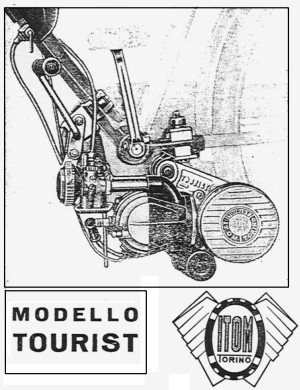

A second version of the same motor was developed to mount behind the cycle saddle and drive above the rear wheel. Then, finally, a more popular third variation was placed between the pedals, driving the rear wheel from beneath the bottom bracket; it became quite well known as the ‘Tourist’ model.

In 1950 Itom produced its first complete cyclemotor with a tubular frame and automatic clutch, which was shortly followed by a two-speed motor version.

The front and rear mounted Itom cyclemotors were imported to Britain in 1951, and were marketed by Adimar of 222 Brixton Road, London SW9; both were replaced by the Tourist model in 1953.

Back in Italy, Itom launched a new Esperia moped in 1953, with a two-speed gearbox mounted in a pressed steel frame. This was followed in 1954 by its Astor and Astor Sport mopeds, with 2- & 3-speed manual gears and pedals.

Itom had started its production making auxiliary engines for bicycles, and still continued building all its own engines as the business graduated towards early mopeds and sports mopeds, which began to set them aside from many other Italian producers, who widely began to adopt proprietary engines from the likes of Minarelli and Morini.

The established Tourist cyclemotor popularly remained in production as a clip-on kit, but also was offered by Itom as a complete cyclemotor-moped in a fabricated pressed-steel frame with girder sprung forks, and called the ‘Alba 48 TR’.

Several similar proprietary cyclemotor frame kits like Casalini and Paglianti had begun to appear on the Italian market, as well as other manufacturers’ own frame kits like BMG, Ceccato, Nasetti, etc, and it can often be difficult trying identify the source of some of the original pressings or fabricated assemblies, so we’re not entirely sure if the Itom Motoretta Alba 48 TR was all their own make, or comprised of a percentage of proprietary bought-in components.

Advertised along with the Itom Micromotore Tourist 48cc clip-on cyclemotor and Alba, was another extraordinary model: Ciclomotore Ideal TC 48, which seemed to have been unveiled in its first appearance at the 31st International Milan Show in December 1953.

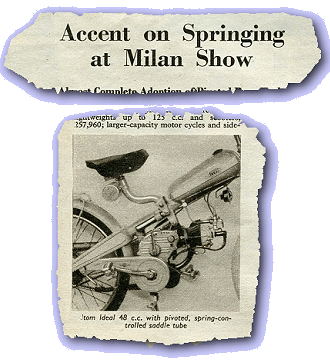

Journalists from the British Motor Cycle magazine attended the Milan Show and presented a report from the show for The Motor Cycle edition dated 3rd December 1953, in an article headed ‘Accent on Springing at Milan Show’, about all the exotic motorcycles on display. They were obviously taken enough by the Itom Ideal to include a passage on the TC 48 with a technical description:

‘Micromotor interest is typified by a new 48cc creation by Itom—the Ideal. The frame comprises of a single, large-diameter tube, which runs straight from the steering head almost to the rear mudguard, where the tube is brazed to a rigid fork of pressed steel; the result is a straight-line frame from head to rear wheel spindle. A down tube which carries the bottom bracket for the pedals at its lower end descends from the main tube at its joint with the rear fork. Front-wheel springing is by a link-action, pressed-steel girder fork. Saddle suspension is by means of a shallow S-shape tube more than a foot long, which at its lower end, is pivoted to the main tube. Movement is controlled by pushrods and compression springs contained in small cylinders positioned one each side of the main tube. The arrangement is such that considerable soft action travel of the saddle is possible in response to rear-wheel shocks.

‘The 48cc two-stroke engine differs from the well known Itom friction-drive cyclemotor only in that it is built in unit with a countershaft which carries a large-diameter cork clutch at one end and a sprocket for the rear driving chain (separate from the pedal chain) at the other. The primary drive is by spur pinions.’

They further included a picture titled ‘Itom Ideal 48cc with pivoted, spring-controlled saddle tube’, right next to a picture titled ‘The sensation of the show is the new Gilera 304cc overhead valve parallel twin’.

They must have been pretty impressed by the little Itom…

It was only a glimpse of temptation for the readership to dream about, however, as the Ciclomotore Ideal TC 48 was never sold in Britain … actually, it hardly seemed to have been sold much at all, because examples are extremely infrequent, and we’ve been unable to find any further references to the machine.

Rare or not, it doesn’t matter, because we’ve still managed to get hold of one…

Ideal’s engine (serial 51159) wears the familiar top-end of the Itom Tourist cyclemotor, with cast-iron cylinder and alloy head but, instead of the expected direct roller drive, the right-hand crankcase is extended to house a manual clutch with an external operating lever on the outer cover. The motor is fed by a Weber carburetter with air control lever—move forward to choke, back for air—and there’s also a flood button on the top of the float chamber.

It’s fitted with a Magnetti Marelli magneto set a with lighting generator powering the Aprilia lamps, which are switched from the left-hand handlebar, beam–off–dip, and an electric horn.

Under the left-hand bar set is a decompresser lever and, above, a manual clutch lever.

On the right-hand bar set: a twistgrip throttle and brake lever … with two cables coming out of the lever bracket, which means it’s got linked brakes. Yes, one hand lever works both brakes—we hope!

The subtle curves of the handlebars are unspoilt by clumsy bolt-on controls, since all the lever brackets are neatly brazed to the bars before plating, while the sturdy cast alloy levers present plain and smooth faces to the rider with no visible cable nipple holes. The control set is commendably thought out.

Moving down to the pressed steel blade girder fork set, we’re unsure whether this is Itom’s own make, but it could well be, because it has a friction damping arrangement on the bottom link with a pressure-adjustable knob marked ‘Itom – Torino – Brevettato’. The bottom link is a straight bar, but the top link is curved … it doesn’t have to be curved, another straight bar would work just as well, but the curved bar looks more elegant.

The fork bottom yoke has a bracket coming off it to match up with another bracket off the headstock bottom, so you can put a padlock through the two holes, making it a very early steering lock.

The top headstock bearing is marked ‘Itom’ all round the edge—more attention to fine detail.

The rigid mainframe (stamped 01164) is a single spine in a straight line from its joint in the middle of the headstock tube to the rear axle; it divides into a pressed-steel loop around the rear wheel.

Another tube drops down from the bottom junction lug to house the pedal bottom bracket, and terminates in a mounting for the centre stand.

The frame is an interesting engineering study for its time, simple, strong, though stylish.

The main frame isn’t sprung, so the saddle-mounting frame is sprung instead. This is a fascinating curiosity, comprised of an S-shaped tube, tension sprung at its bottom mounting by two compression springs in chrome plated cylinders either side of the frame. The stem is topped by an Itom-badged saddle and fitted with a cylindrical toolbox underneath.

A stout tubular rear carrier frame is topped by a Nisa aftermarket pillion pad with a front grab strap, but with no sign of any footrests.

The forward frame section carries a rounded lozenge-shaped fuel tank, trimmed across its centre by a curved alloy strip. The screw filler cap is phenolic thermoset plastic (Bakelite), marked ‘Itom – Micromotori – Ciclomotori’—just don’t drop that cap and break it, because you’d probably never be able to replace it.

Fuel turns on at the bottom right of the tank, maybe we’ll flood and choke because it’s a cold January day here in Britain, and our Itom may be missing its warm Mediterranean climate.

Rotating the pedals only turns the rear wheel, but doesn’t spin the motor, and pulling in the clutch lever makes no difference, so how does this work? Looking around for a likely drive engagement control, we note a round Bakelite knob extending from the front drive sprocket on a spindle. The knob idles on the spindle, and it’s top is marked ‘Itom – Torino – Micromotori’, so that’s helpful! Since turning the knob has no effect, we try pushing and pulling it, but get no movement until we turn the rear wheel a little while pushing in, then the spindle clicks home and locks on a dog drive somewhere in the depths of the machinery.

We can now start on the stand by holding in the decompresser, spinning a pedal like a kick-start to get the motor turning, then releasing the decompresser halfway down the stroke.

After a couple of spins the motor fires and, following a couple more attempts, we manage to keep the engine running to warm.

At this point it’s worthwhile noting that the rear wheel is spinning under drive, so not to push the bike off its centre stand unless you’re holding in the clutch, when you can mount up and pedal assist the take-off while opening up the throttle and feeding in the clutch.

If you do happen to forget the clutch, and nudge the bike off the stand, then it will leave without you.

While inspecting the bike we were also curious about a chrome-plated pipe union connecting to the top of the exhaust pipe, so we lie down to study where that’s going: back to join the decompresser vent on the cylinder head. Another Itom fine detail to make for a silent decompresser!

The exhaust pipe joins a cylindrical can in front of the bottom bracket, then exits out the left-hand side through a tailpipe to carry the oily smoke away from the rider. It creates a mellow popping tone at low revs, raising to a smooth hum as we blip the throttle.

Best on flat was 24mph with tailwind, and Ideal was readily blown down to 20 into a headwind, where the motor didn’t seem to develop enough power to be able to get a better pace up. It felt to struggle so much into a headwind that the rider could be inclined to crouch to help progress.

Downhill run with tailwind was paced at 29mph, which the motor achieved without any four-stroking, and running smoothly at the revs.

Overall the motor felt low on power, so weak against headwinds and light forward gradients.

The clutch lever felt as if it had a long travel, but only bit in the last part of the release, and though working very effectively, it never felt a comfortable operation and we didn’t quite get used to it.

A difficulty with the single-speed &manual clutch operation, is that you do notice the absence of being able to select a neutral, particularly at junctions or in standing traffic; you have to keep the clutch lever held in all the time you’re stationary … or stop the motor then pedal off again to re-start. It’s also an issue when slowing to approach junctions, because you can’t signal left with the clutch lever held in.

A similar difficulty occurs under the same circumstances when slowing to turn right at a junction. Because the bike has linked brakes operated from only the right-hand lever, you have to pull on the brake to slow down, so again you can’t signal!

The wheels are laced onto half-width hubs and the tyres are marked 1¾ × 19¾ (1¾ × 20), which might be a ‘difficult’ size.

The linked brakes actually work well, with quite adequate braking from the single lever, but the controls certainly make it difficult for the rider to indicate.

Presumably dated around 1954, the ride was generally quite good for an early cyclemotor-cum-moped of that period. The friction damper on the girder fork certainly took the bounce out of the springing and stabilised the front better than similar undamped equivalents we’ve ridden.

You were very aware of the ‘floating’ springing working in the saddle mounting frame, and moving to absorb motion from the rigid rear, while the cycle frame still handled confidently under general riding and on cornering.

While the pedal chain was conventionally sized at ½ x ⅛, the main drive chain seemed unusually small, and measured just ⅜ pitch × ³⁄₁₆, which is a size more likely to be found on a primary drive! That’s very odd!

Extensive research efforts to find further information about the Ideal failed to turn up anything else at all, so at this time we no idea how long the model was made for, or how many were produced.

While the Ideal was an imaginative and striking design exercise, it’d be easy to see potential customers being put off by the limitations of its single-speed & manual clutch arrangement with no neutral, and linked brakes, which certainly made it a difficult machine to ride.

Its rarity may be some clue as to the model’s success and, since Itom made its own engines, the company would be in an easy position to readily drop an unsuccessful machine.

1954 introduced the first Astor Sport model, with a three-speed hand change and pedals, which were mandatory for all 50cc machines at the time.

1957 brought out the Astor Sport Competizione moped, rated for 75km/h (46mph) in standard trim. Itom sold a further tuning kit for competition use, comprising a high compression cylinder head on chrome bore cylinder, various types of pistons with either two or three rings, a Dell’orto SS20mm carburetter, and an expansion chamber exhaust. The last competition models tuned with this kit were claimed to be capable of 110km/h (68mph) and without a fairing!

Over 1957–58, Itom moved to larger premises at the former Maglificio Fratelli Bosio plant in Sant’Ambrogio di Torino at Valle di Susa, to expand its production of motor cycles.

1959 launched the 65cc Tabor motor cycle model, initially with a three-speed twist change, 16mm carburetter and rated at 3.5bhp for a top speed of 70km/h (43mph). Later the model was equipped with a four-speed hand-lever changed gearbox, then subsequently converted to a foot-change selector. The 65cc Tabor was the only machine that Itom produced that required registration, since 50cc machines in Italy at this time were exempted.

As from 1959, pedals were no longer a requirement on 50cc machines in Italy, though traditional mopeds with pedals would still have their place. Kick-starts with footrests and footbrakes ushered in a whole new generation of proper 50cc sports motor cycles for the home market, which had previously only been built for export, while export models could still retain pedals for those markets where they were required.

At the end of the ’50s Itom became IMSA (Industria Meccanica Sant’Ambrogio).

In 1960 the Itom Junior model came out, and 1965 introduced a machine that would become the most famous and iconic of all, the Itom Astor Sport with four-speed foot-change gearbox, Dell’orto UA18S carburettor, and producing up to 6bhp @ 10,000rpm for 95–97km/h (60mph). These were typically finished in the classic period livery combinations of a white frame with yellow (or red) fuel tank, tool-boxes, mudguards, and chain guard, with white flashes and black or green lines.

By 1965, Itom had around 130 employees, when on the evening of 26th August, a sudden fire developed in an attic section of the factory, which destroyed the roof of the plant, and caused extensive damage to manufacturing equipment and completed products.

1969 launched the Sirio Cross off-road model, with Astor 4M engine and Dell’orto UB20S carburettor, and a new version of the Astor in 1970.

1972 season dropped the Astor model after 8 years production, and replaced it with a new sport model called the Sprint, which runs a Zanetti engine with head and cylinder from the Astor. Its angular fuel tank is now painted in monochromatic apple green, with a simple Itom logo in white block letters.

In 1973, Itom ceased making its own engines and joined the rest of the herd, fitting proprietary 50cc Franco Morini engines. A new range was presented at the Milan Motor Show in December, including two 125cc machines, one a street-scrambler with Franco Morini engine, and the other called ‘Cross Competition’ with a German Zündapp motor, but both models only remained as prototypes.

Itom also turned to building innovative rotary system air compressors and water heaters for medical applications, but these were a financial disaster, and the losses incurred contributed to the closure of motor cycle production at the Sant’Ambrogia plant in 1975.

In 2010 the road leading to the old plant was named after it: ‘Via Itom’, and in its background, the Liberty building that housed the Itom plant from 1957 to 1975.