The BSA Dandy was almost certainly born out of well-intentioned ideas to produce a keenly priced commuter machine to compete in a rapidly growing market that was largely dominated by imported 50cc mopeds.

It was shortly after this point, that things started going wrong…

There’s not quite any saying when the Dandy project began as such, but the model was most probably developing over 1955, along with the ill-fated ‘Beeza’ scooter, when some misguided management decision felt that both machines should be marketed as quickly as possible, and certainly long before any technical assessment or engineering development had opportunity to appraise their suitability.

The first prototypes of both these new machines were completed only a few weeks before the Earls Court Show so, rather foolishly, it was decided they should be exhibited, and an advance notification was released to the motor cycling press.

In established practice for the time, motor cycling journals prepared ‘Show Preview’ issues to generate interest, and The Motor Cycle rather got off to a false start, in announcing the new ‘Dandi’.

So it came to pass, when the doors of the exhibition unlocked at 10am on 12th November 1955, two completely untested models were displayed on the BSA stand. The halls were steadily filling with three-shilling public admissions, all at liberty to view and examine BSA’s latest undeveloped prototypes, when the official opening was presented at 11am, by Peter Thorneycroft, President of the Board of Trade.

Somewhat remarkably, retail prices were even posted for both machines: Beeza scooter £204–12s (including PT), Dandy scooterette £74–18s (including PT).

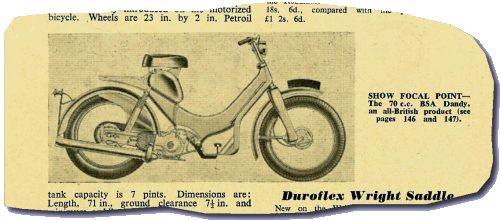

At this point it’s probably worth noting a few specific features from the official description of this model Dandy. Some of these would be changed later on, and are conveniently highlighted for reference.

‘The 70cc two-stroke power unit has a bore and stroke of 45mm × 44mm, and a compression ratio of 7 to one. Aluminium die castings are employed for the cylinder, cylinder-head, crankcase and gear box housing.

"The unit is arranged in a U-shape around the rear wheel with the cylinder head pointing rearwards on the offside, the crankcase running transversely across the machine, and the gear-box housing extending rearwards on the nearside. There is a dry-plate clutch and the final drive is by chain.

‘The carburettor and inlet port are enclosed within the crankcase on the offside, access being through a detachable, cast-aluminium cover, which incorporates an air cleaner.

‘The complete engine gear unit pivots in torsionally resilient rubber and steel bushes from the frame. There is leading bottom-link front fork. Range of movement at the wheel is 2½", front and rear. Pressed steel members, bolted to the cylinder head on the offside and to the gearbox housing on the other, extend rearwards to carry the wheel-spindle; that from the gear housing also forms a chain-guard. From these two pressings, brackets extend upwards and support two coil-springs, which provide the rear suspension and which are anchored at the top ends of the frame.

‘The open loop-type frame is constructed of two large steel pressings, seam welded together, and welded to the steering head tube. The six-pint fuel tank is attached to the frame and provides the mounting for the saddle. A parcel carrier is provided, and a toolbox is built into the frame.

‘A feature of the machine is the two-speed pre-selector gearbox, the pre-selector lever being mounted on the handlebars, which are up-swept. Mounted on the handlebars in a single streamlined housing is a 3½" headlamp incorporating a standby battery and an electric horn. A starting-lever which can be operated by either foot or hand is provided which operates on the gearbox final drive shaft. Wheels are 20 × 2½, and brake sizes 4" by 7/8".

‘The gear ratios are 8.9 to 1 top and 17.3 to 1 bottom—small wheel size should be remembered when comparing these ratios. Dimensions are: wheelbase 45", saddle height 28½", ground clearance 4½", height 33", and length 67". The weight will be less than 85lb.

‘Ease of servicing is an important point with the machine. The complete power-unit and gearbox, together with the rear wheel can be detached from the frame by undoing the pivot bolt. By release of three bolts the generator and clutch housing can be separated from the gear unit’.

Now, to be fair, the general description did vaguely include reference to what would probably become the most infamous of Dandy’s many features, but by the time the marketing spin had finished massaging the release, probably no one, including the unfortunate dealers, would have picked it out of the text or grasped the true implications of what this would involve … Can you spot what it might be?

The Beeza scooter was a handsome machine with a 198cc four-stroke engine equipped with electric starting, which presented a modern and stylish impression. Though the Dandy rather balanced the display with a somewhat primitive and crude appearance, both machines were seemingly well received, and despite the total lack of engineering development, the show closed to the wildly ambitious claim that ‘Production was not expected to commence until Spring 1956’, meaning they were suggesting that bikes would be available and on the market in time for agent ordering by next sales season – in four months!

The general public, of course, had no idea of the true position and, needless to say, this didn’t happen at all.

The promising Beeza scooter actually disappeared completely, never to be seen again, while the 70cc scooterette progressed into the dark tunnel of development… Things might have worked out slightly better if the decision had been reversed, and the Dandy had never been seen again.

In the development phase to production, Dandy became subject to a number of changes, according to various marketing whims, cost constraints, and committee decided engineering alterations. A number of these were to offer little or no real improvement, and one in particular to catastrophically add to the already existing design problems.

It’s notable that the show prototype exhibited an aluminium cylinder, since the original concept was to produce the alloy barrel with a hard chrome bore.

NSU successfully introduced their Quickly moped with this feature and it was a process being developed by a number of other European manufacturers, Motobécane, Zündapp, etc, but at BSA, this method was only in its infancy. Certainly there existed a small division within the group that was exploring the process on an experimental scale but, in 1955, this was nearer the realms of science fiction fantasy than production practicality.

We will probably never know whether the show prototype Dandy actually had just a silver painted iron cylinder, a steel liner in aluminium cylinder, or possibly no finish whatsoever, as it may even have been completely incapable of running at all!

Whatever the answer to this question, the cylinder finning was intended to suitably satisfy the thermal dispersal properties of alloy—along the way, however, someone decided to go into production with a cast iron cylinder.

It’s been suggested this was a cost reduction idea, but it may equally have been a solution to the reality that BSA had no production hard chrome bore capability at the time (or ever, in fact).

While iron air-cooled cylinders are widely used on many motor cycle engines, the heat dispersal properties of iron are appreciably less, so require more suitable finning to account the difference—except that Dandy was produced in the same pattern! Considering the complete absence of fan driven forced air-cooling, coupled with the rear-facing cylinder arrangement that was obviously draft inhibited anyway, this was clearly a rather bad decision.

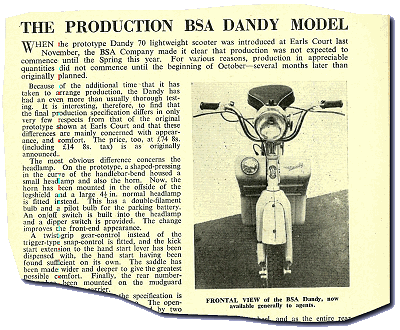

It took considerably longer than the earlier optimistic Spring date quoted before Dandy production models began progressing along the assembly lines in October 1956, and another sales season had already been missed.

Press releases at the end of the month were already representing the Dandy as ‘Manufacturer’s 1957 programme’, and detailing changes from the show prototype.

‘The most obvious difference concerns the headlamp. On the prototype, a shaped pressing in the curve of the handlebar bend housed a small headlamp and also the horn. Now, the horn has been mounted in the offside of the leg-shield, and a large 4½’ normal headlamp is fitted instead. This has a double filament bulb and a pilot bulb for the parking battery. An on/off switch is provided. The change improves the front-end appearance.

‘A twist-grip gear-control instead of the trigger-type snap-control is fitted, and the kick-start extension to the hand start lever has been dispensed with, the hand start having been found sufficient on its own.

‘The saddle has been made wider and deeper to give the greatest possible comfort. Finally, the rear number-plate has been mounted on the mudguard instead of on the carrier.

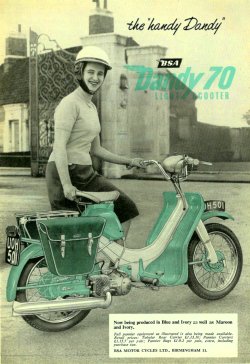

‘At present there are three colour finishes available: Light green (eau de nil), honey-beige, and dark lavender-grey. Wheel rims are chromium-plated, and the silencer is finished in heat-resistant silver-aluminium paint.

‘The price too, at £74–8s (including £14–8s purchase tax), is as originally announced’.

The press release notes neglected to include any reference of the change to iron cylinder … obviously only a minor detail, unworthy of mention.

The Dandy didn’t appear on the market until 1957, when it became BSA’s only new machine for that year.

Glass’s indicates the Dandy engine number series commencing at DS 101.

We find the frame number DS 1709 stamped along the bottom steering head race on our first featured Dandy, and wearing engine number DSE1474, this is one of the early production machines equipped with the hand-start lever, sold from Revett’s Motorcycles in Ipswich, and registered VRT 319 around February 1957.

As we pick the bike up, the owner’s tip is ‘Don’t bother with the stand, just a bent bit of wire and not very good, so I just lean it up… Oh, and I can’t get it to go, perhaps you can sort it out?’

Somehow things give the impression that we’re not off to a particularly good start with this one…

A few hours tinkering to try and coax our mount into life, gives us the opportunity to acquaint ourselves with Dandy’s delicacies.

The frame is commendably simple, and you do have to admire its originality for the time, basically just a press-formed V shape, with a large plastic blanking disc in the left hand crook?

Skimming through the manual, it says ‘The toolbox is built into the left hand side of the frame and has a circular plastic cover’ … which is hard plastic and requires a screwdriver to prise it off, and maybe the screwdriver is in the toolbox? When you finally coax off the cover and look inside, few people could probably imagine it as a toolbox, more realistically just a hole in the frame, covered by a bung—a bit of artistic license employed here we feel!

The ‘technical data’ section advises compression ratio at 7.25:1, which seems to be up ¼ point on earlier notes.

To fill up the petrol tank, hinge back the seat to access the fuel cap, and find the saddle comprises a foam pad on a sheet steel base, with two rubber buffers that stop on indents in the tank. This all seems very minimalist for a saddle claimed to offer the ‘greatest possible comfort’!

We have a look at the ‘bent bit of wire’ stand, which indeed proves to comprise no more than an artistically formed length of 5/16" diameter bar that pivots from a couple of bosses on a brake pedal lever frame, which itself pivots off the footrest bar.

In managing the bike to load it onto the stand, the most practical handling point proves to be lifting from the end of the rear carrier, and it’s nice to find that BSA have thoughtfully finished this tail in a one-inch radial form, that provides a secure and comfortable grip. Which is probably just as well, since the bike requires raising three inches and wobbles back for eleven inches, before settling onto both wheels again, where the stand now seems to act more like a double-sided prop. Teetering in wavering balance like Dali’s ‘Sleeper’, it has to be said—Dandy’s stand is not terribly convincing.

Then look back at where the stand stops against the underside of the motor, and there’s a deep groove worn into the crankcase casting beaded joint, and the bottom of the zinc air filter cover has been eroded away by the right hand stand leg, until the wear rate has slowed when it’s come across the steel bottom screw! Just a well-placed rubber buffer could have saved all the carnage, but too late!

Operating the seventeen-inch long hand-start lever from down in that forward left foot well is completely ridiculous!

What were they thinking?

It’s practically impossible to bend down and operate while seated. The best way to work it is to hop back and astride the rear carrier, rest your chest on the seat and pull in an upward arc as you straighten up—it must have been an interesting operation for a lady in a dress!

The riding position seems generally natural, until you go to put your feet on the footrests, when you find the hand-start lever in the way on the left, and the brake pedal in the way on the right, both rather obstructing putting your feet forward on the rests or quite within the leg-shield. The result is that you have to sit with your feet on the ends of the footrests, and toes turned outside of the leg-shield—like Donald Duck!

Pull the fuel tap plunger on at the bottom front right of the tank. There’s no flood option with the carburetter hidden away inside the engine, just a little choke rod sticking from the case, so we’ll have a bit of that. Leaning over the seat, pull up the starter with your left hand ... phut, phut, phut, nope! Try again … phut, phut, cough! Try again with the choke off … phut, cough, phut. Nearly? Try again … phut, cough, cough, and with a little twisty throttle the motor slowly bumbles into life with a low, flat note gargling from the fishtail silencer.

Running the motor a couple of minutes just to check it’s all settled down, things seem OK, so we decide to give it a go.

Twist the left grip fully forwards for first, but being a pre-select box, nothing will happen till you pull in the clutch. There’s a delayed action ‘clunk’, so that’s probably it, then feeding out the clutch and opening the throttle, just pull off as normal.

Pre-selecting second requires a big handful, twist the left grip right round through some 120° (and it’s a heavy action), then pull in the clutch lever, wait for the clunk, then release again to find the motor is engaged into second (top ratio).

The 70cc motor does, however, labour well against low revs, so will doggedly pull itself up to pace.

A few practice shifts up and down the box soon gives a grasp of the operation, but it’s a slow and ponderous gear change system. The gears prefer to select in their own time, at their own optimum speed, and don’t seem to want to be hurried. Trying to change down prematurely from second to first will induce grinding and clonking protestations from the box, so the rider quickly learns it’s best to avoid that sort of thing (Ah yes, the manual says ‘Do not engage low gear if the Dandy is exceeding 10mph’).

The pre-select gear change novelty soon wears off; the better riding technique is to try to take corners at sufficient pace to remain in top and minimise gear changes, since slow and cumbersome ratio shifts will generally just slow your progress.

With the pace bike as escort, since Dandy has no speedo, the scooterette cruised along happily enough about 25mph, emitting a low, flat drone out of the fishtail. Best on flat clocked 31mph in a stunted crouch, since the ‘traditional’ riding position really doesn’t encourage ‘getting down’ much. In deference to Dandy’s heat-seizure-prone reputation, we only tried this in a couple of measured bursts, then eased back gently to steady running again—no sense in looking for trouble!

Saving all for the big downhill run, pace bike read off our descent at 38mph, and while the engine was certainly getting quite ‘excited’ at this speed, the pilot was also getting increasingly nervous about the prospect of something letting go. This dive-run was certainly faster than any sane person would probably want to try on one of these things themselves, then Dandy charged the climb on the other side, and while constantly fading against the incline, still crested the rise at 22mph in top without the need to have to change down.

Probably expecting the worst from the stubby leading link fork, in conjunction with the crude and exposed coil springs at the rear, the ride was appreciably better than anticipated! At no point over the standard circuit did the rider observe any adverse surface to comment upon.

In accordance with the 2.50×15 (20×2½) wheel & tyre specification we’ve sampled before on Elswick–Hopper mopeds and the Ariel Pixie, handling was well planted, sure footed, and confident in corners.

Running four-inch diameter × 7/8" shoes in the half-width hubs with balancer flange, the front brake gave a heavy feel and proved so poor in operation that it even failed to provoke any reaction from the leading-link forks, while the foot pedal-operated rear brake felt clumsy but adequate.

A switch on the headlamp operates lights, with left for dry cell parking set, centre for off, and right for generator circuit to 6 Volt, 18/18 Watt front and 6 Volt, 3 Watt rear. The headlight seemed pretty bright when we tried it, but then we noticed the rear didn’t come on, so the extra wattage from the blown tail filament was probably contributing to give a bit of a false impression there.

If Dandy’s ticking over and you’re looking to stop it, there’s no cut-out, no decompresser, no switch, and no key—to which the manual says, ‘If the engine does not stop, it indicates that the throttle is not closing properly. Always turn off the fuel or, better still, turn off a few seconds before stopping the engine’. Huh? We guess you’re just not supposed to have it set to tick-over.

Having now experienced our first early production Dandy, what can we do but move on to a later version to see how BSA might have improved the model in light of a little ‘customer feedback’?

The registration serial of our second bike shows NSK 842, which looks suspiciously like an age-related re-issue, so the bike’s traceable history probably looks to have been lost. Wearing frame number DS 4110 and engine stamped DSE ERS2008, this machine isn’t actually all that much later, just over 2,500 bikes down the series, a mere sneeze for the likes of BSA, but a surprising number of detail changes from the early model do illustrate the pace of development in production – and the ongoing attempts to improve initial faults.

The wire stand now pivots from further forward and, fixed by a clamp-plate beneath the leg-shield set, results in a firmer posture as a result. Comparing the lifting arc, the modified arrangement now only raises the bike just one inch, and back 6½ inches. Much easier to operate, a considerable improvement, and it now appears the stand is actually capable of supporting the bike!

Also changed is the brake pedal, which now pivots at a higher position from a boss in the frame, with the whole lever relocated above and within the leg-shield well, rather than the foot pedal coming through the floor from underneath.

Folding back the seat, the now plain petrol tank seems to have lost the pressed indents that the rubber stops nested in. As a consequence, the saddle pad no longer appears to rest horizontally, and now feels to be tilting from the back when you sit down.

A seven-inch long kick-start pedal replaces the earlier hand-start lever, but is still an awkward device to operate, though for different reasons. Because it’s a typical scooter-style, rear-facing kick-start pedal, the arc only begins at 90°, so you only get ¼ effective swing to reach the bottom of its stroke. The pedal positioned behind the rider makes it practically impossible to work left footed from a seated position, so you really need to be stood off the bike to kick with your right foot—except that the pedal only just clears the gearbox, and you’re forced to kick over with your toes to avoid fouling the casing. It’s just another starter that’s still not very nice to work!

The addition of an 11-inch wide by 10-inch long steel-bar rack mounted atop the 6-inch wide by 10-inch long pressed carrier increases the luggage capacity somewhat, but is an accessory one could hardly imagine being fitted to the early hand-start version since it’d then become practically impossible to stand astride the rack to start the machine. Presumably the bar rack must be a later development accessory?

We’ve got a 50mph Smith’s speedo set on this bike, but despite the drive seemingly turning the cable OK, the instrument seems reluctant to indicate anything, so once again, our wing man on the pace bike is called on to take the readings.

Apart from the kick pedal, starting procedure is the same, and a couple of jabs on the kick-starter has our second Dandy chugging into life. Push off the choke and a few revs clear the engine ready to ride.

The clutch proves really savage on this engine, and snatches on so sharply that it’s practically impossible to achieve any sort of controllable take-off, so coupled with the clonky pre-select gearbox, this bike is quite capable of making any rider seem like an incompetent novice!

For some unaccounted reason, both front and rear suspension seemed rather more bouncy than our earlier model, and the general ride felt vague and jelly-like, interspersed with further moments of a different unpleasantness when the front brake was applied, and the fork reared up on its leading links.

With the old starting handle out of the way, you could now tuck your left foot comfortably into the foot well, but with your other boot in matching position on the offside rest now finds your right foot actually sitting below the pedal—not the best position if suddenly called upon for desperate braking.

All the time on this bike, transmission whine in both gears wears at your nerves, and after a five-mile ride, is rather beginning to erode the last vestige of any enjoyment from the journey.

Despite all the niggles, this bike did seem to run a little quicker, recording best on flat in a crouch as 34mph. Maybe a little more confident, or plain suicidal, the downhill run paced off at 40mph, and charging the climb on the other side we crested the rise at 22mph in top—exactly the same as our earlier example.

Again with no speedo to gauge our general pace, it was a little surprising for the marker to report we’d settled to an average cruising of 28mph, and 3mph faster than the earlier example, so maybe some interesting comparison between the performances of different machines?

The hand-twist gear-change now seems to have added a spring loaded secondary latch, that blocks against ‘inadvertent’ changing down to first and requires a thumb operation to release the gate—presumably an effort to address disaster to the pre-select gearbox from premature down change.

It should appear to have offered a solution to the problem, but adds yet another hurdle to the already cumbersome gear change process.

We try the lights and horn, but to no effect, having been told by the owner that the electrical output could be intermittent from a suspect wire connection in the mag-set—and obviously deterred at the prospect of needing to remove the engine and split the cases, etc.

Yes, the old design problems are still cursing surviving Dandys in the 21st century!

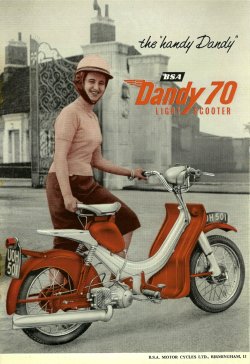

Comparison of Dandy adverts from 1958 & 1959

General motor cycling references indicate the Dandy continued in 1958 with some detail changes, which presumably comprise the differences we observed on our second test machine.

The engine layout from right to left, comprised first the carburettor mounted on the casing and piston-ported into crankcase. The overhung crank journal crosses output, to the flywheel magneto and clutch in the middle of the engine, then into the two-speed, pre-select gearbox at left. From this, a chain down the nearside drives the rear wheel.

One of the main problems lay within this arrangement, since access to the contact points required the whole engine removing from the frame, the main cases parting to access, and one of two different extractors to remove either the Wipac or Lucas flywheels within. All motor cycle agents knew only too well that contact points are the second basic service item to check after the spark plug, and the trade deeply hated the adversity of Dandy’s arrangement.

Why BSA ever progressed this absurd design to production is quite beyond anyone’s comprehension.

BSA fitted both Lucas and Wipac mag-sets to Dandy motors, and to complicate matters further, there was nothing so simple as a fixed point where they changed over from one make to the other. The two different manufacturers’ systems seem to have been randomly fitted right throughout production.

DSE engine serial prefix indicates Wipac mag-set, DSEL indicates Lucas mag-set fitted.

Another Dandy snag lay in the gear-change pre-selector arrangement, which was controlled from the left-hand twist-grip, and gave appreciably more trouble than the simple gearbox methods established on continental mopeds of the period.

Neither did problems end with the carnage of broken gearboxes, but holding Dandy on throttle was inviting piston seizure as the iron barrel invariably failed to dispel its heat. The rear wheel further tended to throw road dirt onto the cylinder and clog its fins, usually making a bad situation appreciably worse.

Step forward Edward Turner as, for its sins, the BSA Dandy proudly features in number one spot on our worst list of bad designs, closely followed in second place by the Honda Camino which requires removal of the engine to service the carb, whereupon the frame collapses!

And third, the stupid Mobylette Cady, which demands removal of the clutch and primary drive—to access the contact points.

We feel the above bikes qualify in the top three, since these are basic service items that should be readily accessible. Machines may usually be lower placed due to general design difficulty on aspects requiring only occasional attention.

Fourth in our chart is the Clark Scamp: you don’t want a back puncture on one of these, since you really need to take the engine off to be able to remove the rear wheel!

Fifth place is the BSA Winged Wheel, which requires complete removal of the mag-set, the left-hand crankcase, and withdrawal of the crankshaft, to be able to take off the piston!

Sixth … Oh dear, it’s BSA again, with the 75cc Beagle and 50cc Ariel Pixie. This is where you have to split the crankcases to be able to remove the final drive sprocket—though isn’t much of an issue with these machines, since the engines always break with some other terminal malady long before anyone ever gets to wear a sprocket out.

Seventh: the Motom 60S kick-start, for being utterly useless, since you have to shift all the way up the box to top gear to use it, then pull in the clutch and change right back down again to first to pull off. After trying this ridiculous novelty to satisfy how it works, riders thereafter just resort to bump-starting.

Eighth position might be the Hercules Corvette, since you have to forcefully prise the rigid-rear frame apart to be able to remove the back wheel, just because you can’t clear the drop-outs enough to release the brake plate stop.

Ninth slot probably goes to the Vespa Ciao, with an equally inaccessible carb arrangement that likely ‘inspired’ Honda’s Camino to copy its popular Italian design, but saved a few places by favour of its Dell’orto carburettor being far less prone to problems than the Japanese offering, and semi-accessible by removing the frame cover plate.

And completing the top ten, we’re afraid this goes to the Stella Mini-bike, where you have to drop the whole leading link suspension set out of both fork legs, just to be able to remove the front wheel—all because it’s just not possible to disconnect the front brake stay. They made very few of these machines, so there weren’t many riders to suffer.

These are our favourite service horrors, but there could be further places just waiting to be claimed with your own nomination—perhaps you might care to send us your offerings?

It’s interesting to note BSA’s official serial progression over Dandy’s years of listing.

| Engine | Frame | |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | DSE 11001 | DS 11501 |

| 1959 | DSE 14462 | DS 15165 |

| 1960 | DSE 18001 | DS 17901 |

| 1961 | DSE 21651 | DS 21801 |

| 1962 | DSE 22164 | DS 22268 |

The figures do rather suggest that the majority of Dandy sales occurred in the early phase, mostly before it developed a reputation. The later years seemed to be barely selling anything at all, presumably after word got around.

The Dandy was officially dropped at the end of 1962, and the year-on-year production figures pretty effectively summarise its epitaph ‘Goodbye to bad rubbish’!

There may be some feeling that the choice of title for BSA’s scooterette was either inappropriate, and may neither have helped with its sales.

While the Pocket Oxford dictionary defines Dandy as ‘1. Man greatly devoted to style and fashion. 2. colloq. excellent thing. US colloq. Splendid’. Larousse says ‘a foppish, silly fellow; a man who pays great attention to his dress. adjective (colloquial) smart, fine, a word of general commendation.’

We quite liked the novelty of testing these machines, and they did ride better than Dandy’s preceding reputation might have led us to expect—but would we want to run one? Er ... No thanks!