From origins in Edward ‘Jack’ Crane’s Petros Cycle Company, two of his sons, Henry (‘Harry’) and Edmund (‘Ted’) Crane began working in their father’s business from the age of 14 by assembling and selling bicycles.

The cycle trade has seen many fluctuations over its time, and by the turn of the century there was a dip of interest in cycling due to the advent of motorised vehicles, which found too many bicycle manufacturers chasing a reduced market. One of the casualties was Petros Cycles, and Jack Crane was declared bankrupt in 1906, so the family were forced to sell their home and move to a smaller property at Lightwoods Hill. With Jack now being a declared bankrupt, a scheme was devised to continue their business by buying new cycles in their mother’s name, then transferring the assets to the brothers for selling at auctions all over the country.

Sir Edmund Crane: cyclist

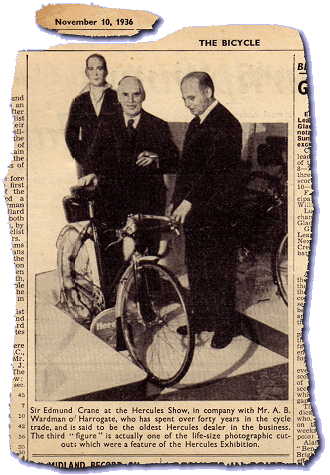

In the very early days of Hercules, Ted Crane pedalled around Birmingham searching for small parts and later, despite presenting himself as the archetypal factory boss (see picture opposite where he has a cigarette in a holder), he remained a cyclist. He is seen in middle of the picture below:

This was on an annual aouting of cycle manufacturers (later to become The Centenary Club) in April 1939. Here his is at a ‘map stop’ on the same ride:

He is on the left; with him are H G Jones (Villiers), J Bayliss (Baylis Wiley), A E Simpson (Raleigh), A D Mayo (Coventry-Eagle), and H N Brearly (BSA).

While this proved very successful, and subsequently allowed them to move back into a larger house, it also attracted the attention of the authorities, which considered their activities as fraudulent and illegal, so raised a case against them. Presumably on the advice of a solicitor as a precaution against being found guilty and receiving criminal records (which could have made it more difficult for them establishing a new business later), Harry and Ted registered a limited company (number 00111679), as ‘The Hercules Cycle & Motor Company Ltd’ on 9th September 1910, and before their trial at Birmingham Assizes in March 1911, at which all the family were found guilty. An appeal was lodged for a later hearing, which repealed the charge on a legal technicality, so they successfully avoided prison.

Harry and Ted had managed to save £25 between them, and decided to rent a derelict old house in Coventry Street to set up a new cycle assembly business, which would trade under the chosen Hercules name as it represented ‘Strength and Durability’. Official commencement date of the Hercules Company was always given as 1911, as it is presumed that production would have started shortly after the appeal finished in their favour at the second hearing. The brothers both worked 16-hour days, as Harry assembled the bicycles, Ted pedalled around Birmingham searching for small parts, while larger components such as frames and forks were delivered by hand cart from other local proprietary builders.

Sir Edmund Crane (centre) in 1936

At first, Ted had problems trying to sell their Hercules bicycles following the legal case against them, but once dealers realised the cycles were cheaper than any competitor’s models, and sturdily built to a better standard, the business began to establish itself on a simple formula of better quality and low price. The brothers started production at 25 bicycles a week, but output had grown to 70 per week before the end of the year, so larger premises were found at Conybere Street, Highgate, in a converted house with a covered yard and small garden … which they ambitiously called Britannia Works. The new site took on ten workers and began displaying business advertisements before Christmas 1911, but the level of trade soon outgrew the available space, whereupon they reportedly even had to pack bicycles on the pavement outside! Hercules motor cycles were also built from 1912, fitting proprietary MMC, White & Poppe, and Minerva engines. Other models were also offered with 3.5 and 4.5hp Precision and Sarolea motors.

Another new site was acquired as part of the former Dunlop factory at Catherine Street in Aston, which could now accommodate 250 workers and, by 1914, Hercules was manufacturing 10,000 bicycles a year and producing motor cycles fitted with Saxon forks, Precision and JAP engines, with an optional two-speed gearbox, or a larger 6hp JAP-engined model with three-speed Sturmey–Archer gearbox.

At the declaration of the Great War on August 14th 1914, the Hercules Company was turned over to the manufacture of shells and munitions. Post-war the business returned to bicycle production, but did not resume motor cycles. By 1921 the pre-war volume had been nearly doubled to just below 20,000 per annum, and Hercules Cycles were now the cheapest on the market, selling new for £3–19s–9d, and delivered in bright yellow vans sign-written with a slogan on the side, proclaiming ‘The Best that Money can Buy’.

Over 1923–24, Hercules completed acquisition of the rest of the former Dunlop factory at Aston, to now occupy the entire 13-acre site. The main entrance was changed to access via Rocky Lane, and the factory was renamed ‘Britannia Works’, where it also became the headquarters of the company offices. In 1927, bicycle production reached the ¼-million mark and, in 1929, Hercules took over another former Dunlop factory less than a mile to the North-West, at Long Acre, Nechells, Birmingham, which came to be called ‘Manor Mills’.

Ted Crane had read Henry Ford’s autobiography and adopted some of Ford’s mass production methods in setting up the Hercules factories. Just like Ford, Crane would not tolerate unions, and paid his workers on piecework rates, claiming he paid 10% above the federation rate of unionised companies, but expected 15% output above the assembly standard in return… In 1931 Ted Crane was described as ‘The Henry Ford of the cycle industry’ by the Daily Herald newspaper, and was certainly a very hard employer, not always liked by his entire workforce, and certainly despised by the unions.

In those days the cycle trade was mainly a seasonal business, and Hercules would employ an extra 1,000 people in January, and lay them all off again at the end of June (which was little different than many short term contract employment practices that still continue in modern industry today). The factories were all run using mass production principles, with the capacity to deliver over a thousand cycles a day from rows of assembly lines, and each bicycle taking less than 10 minutes to build. Hercules’s three millionth bicycle was completed in 1933, with over half the production having been sold for export, bringing in over £6 million from overseas sales, earning letters of congratulation from the King and Prince of Wales, and Edmund Crane was bestowed with a knighthood in 1935. By the close of the 1930s, Hercules had produced over six million bicycles and could claim to be the biggest cycle manufacturer in the world.

Shortly after World War 2, Sir Edmund Crane chose to retire, and sold Hercules to Tube Investments in 1946, for £3.35 million. TI had been the main supplier to Hercules and provided the company with the tubing from which its bicycle frames were made, so the acquisition of Hercules was a means of securing its primary business and adding value by further processes. A third Hercules factory at Plume Street, Long Acre was added in the 1950s, just a short distance from Manor Mills, and making the business one of the largest in Aston.

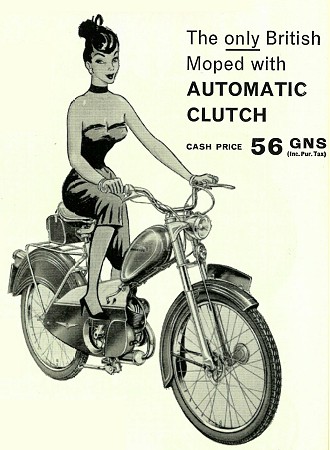

Following a gap of over 40 years, Hercules returned to motorised products with the launch of its first moped as the ‘Grey Wolf’, introduced at the 1955 Earls Court Show, which appeared in manufacturer’s lists from this time. By March 1956 it was apparent the somewhat sombre and austere Wolf wasn’t catching on, so was given a make-over with a few detail changes, renamed the Her-Cu-Motor 2, and entered on production lists from October 1956.

Presentation of the Her-Cu-Motor 2 was also accompanied by display of a Her-Cu-Motor 1 model, using the same JAP engine and Burman gearbox arrangement, though looking more like a traditional autocycle, and mounted in a 26-inch wheel ladies-style cycle made from heavy-duty tubing, with a rigid fork and frame. Prices were initially given as: Mk1 £60–18s, Mk2 £67–4s for display at the Earls Court Show of 1956, but revised upward to Mk1 £63–6s–4d, Mk2 £69–12s–4d for 1957. The Her-Cu-Motor 1 never seemed to have progressed beyond the 1956 show prototype and apparently never went into production. Possibly its autocycle looks were considered too old fashioned compared to all the other mopeds that displayed at the 1956 Earls Court Show.

Towards the second half of the 1950s, the Tube Investments Group was continuing acquisitions to add to its portfolio of companies, but against this backdrop, was also reviewing many of the businesses it had, and these were developing into dramatic times for the cycle trade in general as a lot of rationalisations and redundancies lay ahead. The British Cycle Corporation of Tube Investments was formed in 1956 to manage its cycle-related subsidiaries, primarily in the Birmingham area, namely Armstrong Cycles (formerly of Sherborne Street; Birmingham); Brampton Fittings + Walton & Brown; Hercules Cycle & Motor Co; Phillips Cycles; Norman Cycles at Ashford in Kent; Aberdale & Bown at Bridport Road, Edmonton, North London; James Cycles; the former businesses of Raynal and Dunelt cycles at Rabone Lane, Smethwick; then later adding Wrights Saddle Co & Fittings, and Sun Cycle Co & Fittings as these further businesses were acquired in 1958.

Brampton Fittings historically operated its cycle parts business from a given address of Phoenix Works, Downing Street, Handsworth, and was also associated with Walton & Brown Cycle Fittings Ltd (formerly of 315 Summer Lane, Birmingham). This Downing Street premises was intended to become the centre for a number of the amalgamated BCC businesses operating in this area from the various local sites. Activities were planned to be concentrated into a large factory area based around the Downing Street premises as a central address, but large redundancies would result.

In 1956 following deadlock with the unions refusing to reform working practices, Tube Investments made 1,250 employees of the British Cycle Corporation redundant, many of these workers being from Hercules factories. Building of the Hercules Her-Cu-Motor moped at Britannia Works, Aston ended in 1958 when Villiers terminated supplies of its JAP engine. The unique arrangement of this machine meant that no other motor could be installed. The Her-Cu-Motor had been an inexplicably and bizarrely engineered machine and the end of production spared it from being a bigger economic disaster from its miserable sales record and lack of customer appeal.

1957 Hercules advertisement for the

Her-Cu-Motor moped and the

New Yorker bicycle

Production at Hercules Manor Mills factory also concluded in 1958, resulting in the loss of 700 jobs from the site as manufacture of components transferred to Phillips Lion Works at Newtown, Montgomery. Remaining business from the Hercules Cycle & Motor Co Ltd of Britannia Works, Rocky Lane, Aston, relocated to the Downing Street premises, which was subsequently re-titled as Britannia Works, Handsworth. The Aberdale directorships were formally relinquished in January of 1959, and on 27th February Tube Investments advised the press that ‘The business of the Aberdale Cycle Co Ltd has transferred to Britannia Works, Handsworth, Birmingham 21, as part of the new buildings of the British Cycle Corporation’ (now sharing the address with Hercules and James Cycles; at the former site of Brampton Fittings Ltd). Despite all the disruption to its cycles operation, Hercules managed to continue working on a replacement for the discontinued Her-Cu-Motor moped, and had been developing a Lavalette-engined Paloma machine towards production.

The unusual T-section oval-formed tube frame seemed to be based on an earlier rigid Paloma design, but the Hercules rigid-rear frame section was a different arrangement and was produced from within the TI Group by Reynolds Tube Manipulators, who also provided the frames for Hercules’s earlier Grey Wolf and Her-Cu-Motor mopeds, as well as frames for Phillips Gadabout models. The frame carried the same forward-mounted fuel tank as the previous Her-Cu-Motor moped.

Being part of the British Cycle Corporation, its forks, heavily valanced mudguards, rear carrier and stand were also common to the Phillips Panda Plus Mk2 moped, which was released at exactly the same time, so the Hercules looked to have been partly developed as a group joint project with Phillips. The French AML Motul Lavalette engine was 40mm bore × 39.6mm stroke of 49.6cc capacity in a cast iron cylinder, with an alloy head of 6.1:1 compression ratio, and rated at 1.8bhp. The VM magneto was Lavalette’s own make, though fitted with a larger lighting generator coil of 18W output as specified for the UK market, since the standard was only a 12W ‘marker’ coil for Lavalette’s own Paloma brand and other continental customers. The clutch employed a secondary starter-clutch set, with a single-stage automatic main clutch, and outboard belt drive to a cast zinc reduction flywheel, then final chain drive to the rear wheel. The throttle control and lever sets were Amal, but breathing was through a Gurtner D12 carburettor, while the quaint exhaust down pipe appeared like an inflated banana, and ended in a cylindrical silencer beneath the motor. Hercules’s assemblage of its selection of off-the-shelf parts from different manufacturers was then disgraced by large and unsympathetically styled side-panels in composite steel and aluminium, while the light blue and white paint job with pinstriped dream topping suggested the rider might be an aspiring ice-cream vendor, and the Corvette didn’t look set to give its competition too much cause for concern.

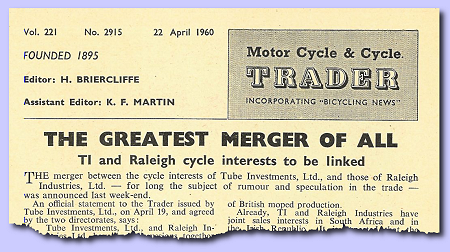

The merger of TI and Raleight is announced to the trade.

Hercules Cycles introduced its new Corvette moped built from the Britannia Works at Handsworth in April 1960, while the Tube Investments Group was settling terms for the take-over of Raleigh Industries, which was announced at finalisation of the deal on 19th April 1960. Glass’s Index indicates some sort of sequence to the Corvette numeration system. Frame serials are shown as starting at AZ1001 in April 1960 with engine no. 501563, and seem to end with HZ1013 and engine no.1004688 in December 1961. So how many Corvettes were actually made? Well, we don’t really know, because there are some aspects of the frame numeration code that still remain a bit of a mystery. Engine numbers aren’t really relevant since Lavalette motors were used in so many other machines on the continent, so the seeming balance of 503,125 engines is completely meaningless. Frame numbers AZ to HZ suggests there were eight prefixes over 20 months of production, and presume that each four-digit number series started at 1001, but we don’t know what number each series ended at. One might consider that each series could end at 9999, but there have so far been no recorded frame numbers higher than 2690. Surviving examples of the Corvette are few and far between, and there aren’t really enough frame serials recorded to help much toward figuring the code out. Frame serial CZ 1240 seems to be our earliest recorded machine so far, but there isn’t exactly a lot to go on. Glass’s also enters the Corvette model as HC5, but we’ve never seen that reference used anywhere else, and seemingly not anywhere by Hercules themselves, so it’s a bit of a mystery where that came from…

Hercules seemed to start changing cycle fittings on the Corvettes almost as soon as they entered production, the very earliest models reportedly built with French ‘Prior’ half-width aluminium hubs, and 52-tooth first type rear sprocket to suit that hub. Hercules probably started with hub types that Paloma were using at the time, but very quickly switched to cheaper hubs made within the TI group that Phillips were fitting to their Panda and Gadabout mopeds. The hubs already seemed to have changed by the time the Illustrated Spare Parts List booklet was printed, which shows chrome plated, steel type, half-width hubs with balancer flanges for front and rear, with a different second type of rear sprocket to suit, and this hub change would have needed different brake plate stop arrangements on the front fork and rear frame. Still within 1960, the rear hub had changed again, to a British Hub Co full width hub, and now a third type of sprocket to suit the Motoloy hub.

Serial DZ1646 becomes our first featured bike, and came as a total wreck in 1980 with its frame sawn in half, a seized engine, jammed wheels, and many parts missing. It was returned to running order in 1995, then re-registered, MoT’d and taxed in 2000 using parts ‘borrowed’ from frame GZ2690. Subject of our previous Hercules Corvette feature (now in The Moped Archive) in April 2001, the bike has subsequently campaigned at many club events. The donor parts were eventually replaced by a mix of Phillips Panda Mk2 components, an acquired spare side panel and front mudguard, and reproduction rear carrier in a 2013 rebuild, so the borrowed parts could be returned to frame GZ2690 and allow reconstruction of that bike back into a complete working machine again. Some may have been hopeful that the rebuilt DZ1646 frame might have looked a little smarter after its recent reconstruction, but these latest pictures show that its decrepit character has not only been faithfully preserved, but maybe even enhanced. It’s probably fair to say that this really isn’t a pretty bike. Yes, it looks like an old wreck, but it’s now 57 years old, and has remained in continuous use for the last 17 years!

Dated at 1960, characteristics of DZ1646 are a half width steel/chrome front hub with balancer flange, full width British Hub Co. Motoloy rear hub with ‘slotted’ 52-tooth type-3 sprocket, and laced into gunmetal painted Dunlop Endrick 19×1.2 36-hole Endrick pattern rims. It’s worth noting that these particular rims were never chrome plated on early Hercules Corvettes, and also as fitted to the Phillips Panda Mk1 moped since its introduction in February 1959. This machine wears a Huret 40mph speedometer set, which was fitted as an aftermarket accessory kit using a handlebar mounting bracket, because the original Miller headlamp shell at this time was a blank pressing, while later shells would feature a speedometer socket. Brake operation is by orthodox cycle hand levers, so with all conventional controls, there are no particular considerations to deter even the novice rider—so off we go!

The dainty centre stand was clearly never intended to take any stationary starting efforts, so these are machines that should always be pedalled away down the road. Fuel turns on at the bottom left of the tank with a plain Ewarts plunger tap, just pull for on. The choke clicks down to spring release when the throttle is opened, but when you pedal off, you quickly awaken to realise there’s no decompresser facility to the Lavalette engine, so it takes a fair bit more effort to get the motor spinning, and requires just a delicate take-up on the throttle to start the motor firing without tripping the choke, then allowing the motor to warm for a few seconds before opening up. Right from the outset it’s pretty obvious that this is not a very rider-friendly method of starting.

According to the makers, the centrifugal locking clutch isn’t supposed to come in until 9mph is reached, but on this bike occurred almost immediately, so required pedal assistance to pick up working revs. The motor readily picks up speed, and with its moderate intake surge and roaring exhaust, feels strong enough to suggest the maker’s 1.8bhp claim is pretty fair. Comfortable cruising indicates on the bouncy needle Huret approx-o-meter around 25–30mph, and on the flat would run consistently along above 30mph, but vibrations particularly on the handlebars would start to become tiring if that were maintained for long. The makers claimed 37mph maximum, but our pacer only managed to clock several bests on flat of 34mph upright with a light tail wind, or the same in crouch against crosswinds, though it’s probably fair to expect that a newer and ‘tighter’ engine might have achieved more, whereas our old and loose example was dropping some of its revs in generating vibration instead. The downhill run paced at 40mph, which was only achieved under much protest from the obviously over-revving motor on the brink of exploding, then we charged into the following uphill. Corvette attacked the hill gallantly for an old automatic, battling the slope to crest the rise at a creditable 24mph, so it certainly tries to give a good account of itself on inclines. The four-stroking issues that affected our previous test of this bike in 2001 seem to have been resolved by replacing a leaky float in the carburetter, but pulsing the twistgrip to throttle-on the engine does make it run noticeably happier under load, which is a typical symptom of a slackening big-end bearing, and seconded by the vibration at revs on constant throttle. The accompanying ‘throttle-on’ sound produced from the carburetter intake and the roaring exhaust could however be misinterpreted as a race challenge to any accompanying rider, so pulsing the throttle to smooth the ride is something that is best done with a little discretion… The lever & cable operated rear brake is appreciably less effective than the same British Hub Co unit in other back-pedal, rod operated mopeds like the Norman Nippy or Phillips Gadabout, which demonstrate the comparative weakness of the cable arrangement. The front brake efficiency was also somewhat conservative, so some degree of forward thinking riding technique is probably recommended. The unshielded outboard belt pulley unsurprisingly proves to be as vulnerable to rainwater ingress as it looks, and under wet conditions may readily slip the drive belt, so it’s best to maintain a firm tension. The 5-inch Miller headlamp produces a typical dull golden glow from its 6V × 15/15W bulb, but at least it’s a bigger glow than a lot of other period mopeds, which invariably had smaller headlamps.

Even for a rider of average build, it just doesn’t seem possible to find a happy riding position, since the frame appears to pitch the seat too far forward. With the handlebars set back for an upright stance, they come too close and low for comfortable turning control, and the grossly over-sprung forks give a harsh ride. To negate these effects the bars are adjusted to a forward hunched position to put more weight onto the forks, which feeling more solid and sporty than an upright position, can become quite tiring to the wrist and arms over moderate distances.

The board at Raleigh was enlarged with a new director appointed from Tube Investments, and joined by the Managing Director of the British Cycle Corporation, to now control all component manufacture, cycle building, and motorised activities of the TI Group. Destiny of the BCC was now handed to this new Raleigh management, who came to a decision to rationalise the number of group cycle brands, and move toward use of Raleigh designs and standards since that brand was now larger and better known in the greater domestic market, and following a steady decline in other branded exports.

In October 1960, Raleigh de-listed their Sturmey-Archer powered RM2c moped.

Our second Corvette is frame EZ1246, and was originally registered from Lincolnshire Authority in November 1960. The remains of this machine were acquired in very poor condition, and comprised little more than a partial kit of corroded parts, and there were no wheels. Some components were salvaged from a reportedly very early model Corvette that was scrapped in Leicester, including aluminium half-width Prior hub rear wheel, type-1 sprocket with long outer slots and a band of inner holes. This appears to be the same Prior hub and brake-plate as used on early Mobylettes, and is fitted with a 52-tooth Ideal first type sprocket, (listed under a Mobylette part no.15260). The hubs were rebuilt with new Westwood pattern chrome rims and stainless spokes. The back brake plate stop was relocated on the frame to suit the hub and the cable anchor feature was welded to the brake-plate stay. The front brake-plate stop was relocated on the front fork leg. A stainless steel speedometer bracket was made-up for a 40mph, triangular, silver faced Huret, mounted across the handlebar clamps. We believe this machine would have originally had a half-width chromed steel front hub and, once again, it is missing the top trim of the right-hand panel.

We note the fitted Ewarts plunger fuel tap on this bike is now a reserve type, pull for on, then turn and pull again for reserve. Starting this machine employs much the same procedure as the other, except that the starter clutch shoes have been relined on this machine, so the clutch more readily bites to start turning the engine over. This can make starting a little harder because there’s no decompresser to help get the engine spinning, and it’s not possible to build up so much pedalling momentum, which requires the rider to use even more effort to pedal through the compression. Fortunately the engine catches to run quite readily, because if a Corvette proves reluctant to start, it can be quite a sapping experience. With the engine turning over, ease the throttle open slightly so as not to release the choke latch, and the motor fires then, briefly leaving it to run on choke till combustion starts to falter, before opening up the throttle to release the choke slide and run clear. It generally helps to keep bursting the throttle open initially to make sure it doesn’t die out, or you might be finding yourself pedal starting again. Corvettes are probably fine for young and fit legs, but may not suit everyone… Clearing the throttle we get underway for another test run with our pacer shadowing the ride. EZ1246 readily pulls up its revs, even on a cold motor, but also seems to be aided by what initially feels like a low drive ratio, where we start to become overly aware of the buzzing revs between 20 & 25mph indicated on the period and classy 40mph triangular Huret speedometer with silver faced dial, which makes it look like a proper instrument. Maybe our impression is not so much of a low drive ratio, as vibration, which is coming through the pedals already and, as we try running a little faster, some of the tinware starts drumming like a Caribbean steel band. This bike certainly experiences some vibration issues, and by the feel of things there’s going to be something vibrating at whatever speed we chose to run at. The motor is an ‘old growler’, and feels as if the big-end and small-end bearings have developed a little too much slack in them (seems to be a common theme with these old Lavalette engines). The engine feels acceptable enough running lower revs up to 25mph, but starts to grumble beyond that, while different cycle frame fittings resonate and sing along with the motor as the revs increase. This engine doesn’t like running fast, but settles down a little better as it warms up, holding a constant 25–30mph indicated, and we urged it on to a paced best on flat of 31mph, but you could feel it wasn’t happy, so we didn’t want to push it any further. Thinking about the possibility of a breakdown, and maybe the prospect of pedalling the bike if the engine failed, we did note that the mechanism which engages the drive on the zinc cast belt flywheel is locked by a large nut on these machines, so isn’t something that could be readily switched over to pedal mode without a suitable spanner—and there is no toolbox provided on a Corvette, so you might even have to carry a spark plug spanner in your pocket at all times… As usual, the over-sprung front forks delivered a hard and bumpy ride. The rear brake tended to groan a little at low speed, but stopped effectively enough, while the front brake worked fine, so those beautiful half-width alloy hubs don’t just look pretty in their chrome Westwood pattern rims with stainless spokes and 2.00 × 19 Cheng Shin tyres. This bike may not be an original example, because of the changes to fit the hubs, but the conversion looks to have been worth the trouble. The 5-inch Wipac headlamp with one-piece glass lens and rim comes from an early Raleigh RM9, but suits so well, and the cream colour of its shell didn’t even need painting to match. Pity the lights barely worked beyond a dim glow to the bulb filaments, because only a Paloma ‘12W marker’ generator coil was available to fit the engine, so it doesn’t create enough power to drive the total 18W lighting set.

By 1961 the steel half-width hub stock must have been exhausted, because Hercules now started fitting a British Hub Co full-width Motoloy front hub to match the back and the Miller headlamp shell now had a speedometer socket closed with a removable blanking plate.

On January 15th 1961, 1,000 workers at Phillips Smethwick factory stopped work for the rest of the day, in protest against a BCC announcement to concentrate cycle production at Nottingham. The following day, cycle production at Raleigh was cut back 30% due to falling orders and built-up stocks, with 7,000 employees going to a four-day week from January 27th.

In February 1961, Raleigh introduced its new RM4 moped, a licence-built machine based upon Motobécane components and assembled at the Raleigh Motorised Products Division in Nottingham.

Frame GZ2690 dates as a late 1961 model, and was acquired as just a rolling chassis with no engine or registration in year 2000, purely for the purpose of donating parts to frame DZ1646 and get one working machine. After DZ1646 was reconstructed with its own components in 2013, GZ2690 reclaimed its original parts and was returned to working order with an engine reassembled from parts. Characteristic features of this machine are full-width British Hub Co Motoloy front and rear hubs, with slotted type-3 52-tooth rear sprocket, and Miller headlamp with speedometer socket filled by a Smith’s blanking plate. Having no speedometer, our test run would be reliant on the pace rider. The established starting procedure was exactly the same as the other two machines, particularly the seemingly essential process of easing the throttle open slightly so as not to release the choke latch to get the motor to fire, then running to warm before opening the throttle to clear the choke. The snatchy starter clutch and lack of a decompresser again meant appreciably more effort to pedal was required to get the motor spinning. Happy cruising was again found in the mid to upper 20s, above which the increasing vibration and noise from drumming panels becomes somewhat tiring. Our best on flat paced at 31mph, and downhill run clocked 39. The uphill climb slowed to 19mph before cresting the rise, but capably dealt with the ascent, and we were always confident that it wouldn’t require any pedal assistance. The brakes proved capable at all times, and the lights almost shone as the most effective of the three bikes so far. It quickly proved essential to pedal assist out of junctions when the single stage clutch is locked on, since it only seems to disengage on this bike if you actually stop, so for an American style ‘rolling-stop’ you will probably need to be prepared to pedal assist on most occasions.

From our highest recorded Corvette frame number, we now return to our lowest recorded serial number, for reasons that will become more obvious, because this machine has become somewhat modified, and is no longer representative of a standard vehicle. Frame CZ1240 wears our earliest recorded frame number, is our only example still retaining its original registration number when it was purchased new on 4th July 1960, and still wears its original engine number 1000161. The bike only transferred to its second owner in 2011, but in extremely dilapidated condition and completely missing its rear wheel, so a replacement wheel from a Raleigh RM4 (Atom full-width alloy hub) was adapted to suit, and fitted with a 48-tooth rear sprocket to gear the main drive ratio up by 7.8%. The decomposed original half-width width chromed steel front hub with balancer flange was also exchanged for a matching (Atom full-width alloy hub) Raleigh RM8 front wheel, which required using a different 80mm rear brake-plate to suit the fork mounting, and repositioning of the brake-plate stop in the front fork. Condition of the engine demanded complete rebuild, and was re-bored (from standard 40mm) up to 41.5mm, now making the motor 53.6cc. The cylinder head face was skimmed back to the fin, and now runs without a head gasket, so compression is probably in the order of 8:1, then the original Gurtner D12mm carburettor replaced by a Gurtner BR13mm, and fitted on a short intake directly behind the cylinder (replacing the original long-elbow manifold). This replacement (ex-Mobylette) carburetter also features a cable-operated plunger choke, so is somewhat more user-friendly to starting. While the starter clutch has recently been relined to improve starting, what may not seem so helpful is the increased compression ratio, since the Lavalette engines have no decompresser and can be difficult starting anyway, so we are a little apprehensive that may involve more effort. Fuel on and pedal off while holding the choke trigger and hope for the best.

We’re surprised that this bike very noticeably requires more speed building up before the starter clutch engages (suggesting a stronger spring), and spins the motor straight away, but doesn’t actually start until we release the choke trigger, probably suggesting that’s making it over rich. We brake to a stop and run the motor to warm a little before pulling away, while our pacer takes up station astern. As the centrifugal clutch shoes again lock in prematurely (as they all seem to do on these motors), we really notice the effect of the raised drive ratio as the engine lugs against the flat spot of dropped revs. Power pulses from the motor feel stronger than our previous machines, so there is an observable difference from the capacity and compression ratio increase, as the motor pulls up through the lower revs. It’s also quickly obvious that the engine is prone to four-stroking unless it’s being fed throttle, another likely sign that it’s running rich. Readily picking up the pace, the gearing increase makes a huge difference in reducing the vibration by lowering the revs—this is definitely the smoothest running Corvette of our set. Cruising with minimal vibration is a very significant improvement to rider comfort, but the tired old cycle saddle with saggy springs most certainly isn’t! Glancing down at the handlebar-mounted speedometer, it’s 3.58? Ah, it looks like a speedometer, but that’s a clock! Best paced on flat was 28mph, with the bike being readily blown down by any headwinds, suggesting the motor was probably over-geared to the present power output of the engine. Though expecting more, the downhill run only paced a peak of 33mph, with some feeling that it wasn’t getting up to revs because of running over rich. Despite the raised gearing, the uphill run however gained strength from the extra fuel and compression ratio, with a hearty show of not slowing below 24mph on the climb. The brakes tended to eerily creak at low speed, but worked fine, the bike handled well enough, though the front forks felt typically over-sprung when they came to any bumps in the road. The raised gearing was a considerable improvement at reducing vibration and rider fatigue; while further adjustment of the fuel mixture and bedding in of the recent rebore will probably deliver improved future performance.

In April 1961 an announcement from the newly titled TI Raleigh Industries Group outlined further restructuring of factories of the British Cycle Corporation. Forthcoming closures were announced of Norman at Ashford; Sun Cycle & Fittings Phoenix Works at Aston Brook St; J.B.Brooks (saddles) in Great Charles Street, Birmingham; and Wrights Saddle Co of Dale Road, Selly Oak. A question hung over the Phillips Lion Works at Newtown, and it was stated that, over the next three years, manufacture of all bicycles for the group would relocate to Nottingham, while mopeds, scooters, motor cycles, saddle work & luggage from Brooks and Wrights was to concentrate at the Downing Street, Britannia Works. On 30th August 1961, Charles and Fred Norman retired as the Ashford factory doors closed for the last time. Though the Norman factory was now closed, new Norman Nippy Mk5 and Lido Mk3 models were listed from September 1961! New Phillips Panda Mk3 and Gadabout Mk4 models also were listed from September 1961, though never rolled down the factory lines at Credenda Works. As derivatives of the Raleigh RM4 and RM5 models, these were actually built from the Raleigh Works in Nottingham, while Phillips Credenda Works at Bridge Street, Smethwick also now appeared to be in the process of winding down. Phillips and Norman mopeds had now become no more than a group-assembled and market-branded product.

The ‘intended relocation over 3 years’ of all group mopeds, scooters and motor cycles to concentrate production at the Downing Street, Britannia Works in Birmingham as stated in April 1961 ... never happened! Raleigh’s established motorised division in Nottingham continued to build all products.

After a production run of just 20 months, building of Hercules Corvette mopeds officially ceased in December 1961, and by 1963 there seemed very little recognisable remains of the former Hercules Empire. With its factories all disbanded in the early 1960s, the Hercules brand was dropped, though its name remained on the companies register under the TI Raleigh Group, until being finally dissolved on 2nd December 2003. However, along with BSA and Phillips logos, Hercules cycle branding still continues under the auspices of TI Cycles India. The Hercules Cycle & Motor Co. Ltd company records are retained at the National Cycle Archive.