Sponsored by Paul Efreme,

East Anglian Cyclemotor

Club,

Essex ‘Chapter’.

There’s traditionally something a little less conventional for the third feature, and we pick up the main theme of this story in 1916, as Danish engineer Jorgan Skafte Rasmussen founds a factory in Saxony to produce steam fittings, and in the same year attempts to build a Dampf Kraft Wagen ‘Steam Engine Vehicle’. In 1919 he made a toy two-stroke motor called Des Knaben Wunsch ‘The Boys’ Desire’, then enlarged and developed this into a motor cycle engine titled Das Kleine Wunder ‘The Little Marvel’, which becomes more commonly credited as the real beginning of the DKW brand name. Manufacturing was established at a factory in the east German town of Zschopau and, by the 1930s, this would grow to become the world’s largest motor cycle producer.

Jumping forward in time to the subject of our presentation: DKW introduced its new Hobby scooter in 1954 and, being quite a different animal from the bikes we typically review, we’ll have a little look around first to assess its general features.

Instead of the typically expected disc wheels for a scooter, Hobby rolls along on 16"×2.50" spoked rims, with conventional drum brakes both ends. Also not particularly common for a period scooter, the front forks are telescopic, with the whole upper assembly enclosed in an irregular shroud that looks more industrial drainpipe than styling, and is capped by a flat crown that mounts a 60mph VDO speedometer marked for DKW, so presumably made specifically for them.

Skimming through DKW’s Hobby manual, it claims the scooter to be ‘The only two-wheeled vehicle fitted with an infinitely variable automatic gearbox—the system is called Uher’, so investigating under the gloomy cover of the rear body shell might allow us to shed some light on the secret workings of these mysteries? The one-piece steel body shell hinges from the front once two 10 millimetre bolts are removed from just above the passenger footplates, but doesn’t raise far before it’s realised that you also need to remove the driver’s seat pad (3×6 millimetre bolts), to fully raise the shell. The petrol tank goes up with the body shell, and pretty much allows access to most of the motor for servicing, though the cover doesn’t securely remain in the upright position so it’s probably best to have something handy to tie it with. The hinge pins can be withdrawn, and the whole body shell lifted away for more unrestricted access.

Basically, it’s a belt-drive CVT (Constant Variable Transmission) primary drive system that has pretty much now become universally adopted for practically all small capacity scooters. The only fundamental difference of this early DKW set is that it features a manual clutch to effect engagement of the front outer cone in driving the belt, so with the clutch lever held in by its griplock latch allows the motor to idle as if in a neutral gear. Final drive is delivered by chain, which is fully enclosed in a two-piece case. Rear suspension comprises a simple swing-arm arrangement acting on rubber buffers in compression and rebound, so we probably won’t be expecting any luxury ride from that system!

Up front of the compartment sits the engine unit, a single-cylinder, fan-cooled, 75cc two-stroke, of 45 millimetre bore × 47 millimetre stroke with 6.3/6.5:1 compression ratio, and fed by a 14mm Bing carburettor, for a given 3bhp @ 5,000rpm.

Many of these ‘old generation’ scooters are quite substantially constructed, and Hobby certainly doesn’t appear to have been built with much economy of materials in consideration for the low power and small capacity engine that has the job of hauling round this assemblage of fabricated steel and aluminium die-castings. Hobby weightily tips the scales (wet), at 12 stone 10 pounds, a portly 178 pounds or, in metric for a continental machine, that’s 81 kilogrammes. As well as being lined with aluminium trims, the rear body shell seems generously ventilated by a liberal scattering of assorted louvres, grills, portholes, and ornamental grids—probably some design version of hedging their styling bets: add a bit of everything and you can’t go wrong?

As well as the DKW badge, our Hobby scooter is also marked with a somewhat familiar logo of four circles in a line, and Auto Union branding, so let’s take this suitable break from the scooter to track a little more of the wider background.

Today, the four-circle logo is most commonly associated with the Audi Motor Company, but there’s a long and chequered history behind this connection...

Leaving his post as production manager to Karl Benz, August Horch went on to jointly establish his first company in partnership with Salli Herz on November 14, 1899 at Ehrenfeld, Köln, and relocated to Reichenbach im Vogtland in 1902. On May 10, 1904 he founded Horch & Cie Motorwagenwerke as a joint-stock company to manufacture motorcars at the industrial centre of Zwickau in Saxony. Following boardroom disagreements, Horch left to form a second motor company on 16 July 1909, as rival to his original business, and calling this August Horch Automobilwerke GmbH, also in Zwickau. A title challenge from his earlier Horch company recognised this as already being a registered brand, so now seemingly holding no rights to re-use of his own name, August faced the prospect of renaming his new concern...

Horch (pronounced Horsh), and taken from the German verb hören (to hear), Audi was proposed as the Latin translation of its founder, and the Audi Company was registered on 25 April 1910, making Horch motors under the rival brand. August Horch left Audi in 1920 for a senior position in the transport ministry, though he remained a member of its board.

Connection to our story came in 1928, since established local companies were attracting attention as DKW sought opportunities to expand, and Jorgan Rasmussen acquired Audiwerke to extend his business interests. Also in 1928, Rasmussen purchased shares in Schüttoff, who had been building motor cycles at neighbouring Chemnitz since 1924, which subsequently introduced models with DKW engines. By 1932 the firm had become fully absorbed, and the brand disappeared. The Auto Union came about on June 29, 1932 as a result of the amalgamation of four companies, DKW, Audi, Horch and Wanderer; hence the four ring badge, one for each of the companies joined.

Fourth member Wanderer, established as Winklhofer & Jaenicke in 1896, initially making bicycles, then progressing into motor cycles, cars and vans. The Wanderer brand was adopted from 1911, with the company making civilian machines up to 1941, and military vehicles until 1945. Wanderer was owned by the Dresdner Bank in 1929, and as the Great Depression began to bite, the firm collapsed, resulting in the sale of its motor cycle side of the business to Frantisek Janeček, who moved this production to Prague as JAneček–WAnderer, and later shortened into another familiar and enduring brand—Jawa! The rest of the Wanderer business was subsequently divested in the Auto Union merger of 1932.

Auto Union is most iconically remembered in evocative celluloid images of awesome rear-engined racing cars from the last years of the ’30s decade, as the technical advances of German ‘Silver Arrows’ Auto Union and Mercedes Benz motor sport teams dominated motor racing from 1934, until the outbreak of the Second World War.

Auto Union factories were turned over to military production during the conflict and, consequently, attracted heavy bombing from Allied air forces. They were further severely damaged by fighting in the last two years of the war. The US army occupied Zwickau on April 17, 1945 but, following withdrawal of US Services on June 30, 1945, Saxony and Zwickau, including the Horch/Auto Union racing facility and Audi plants, were re-occupied by the Russian Red Army. On orders of the Soviet military administration, elements of the factories were dismantled as war reparations, while an estimated eighteen ‘Silver Arrows’ team racing cars were found stored in a colliery by the Russians, shipped back to Moscow for ‘research’, then distributed to scientific institutes and motor manufacturers for analysis.

While most of the cars were probably reduced to scrap, so far, five vehicles have been recovered, ranging from collections of parts to almost complete cars. Restoration work has been carried out by British firms Crostwaite & Gardiner, with Roach Manufacturing, giving us the surviving Auto Union racers that can be seen today.

With the Wanderer plants at Siegmar and Schönau completely destroyed by the end of the war, manufacturing was never restored at these locations.

In 1947, the former DKW factory at Zschopau returned to the production of single cylinder two-stroke motor cycles up to 298cc. Though largely based upon previous designs, there was also a new 350cc two-stroke flat twin (mechanical disaster).

Since a lawsuit prevented the East Germans from using the DKW brand, the products were badged as IFA (Industrieverband Fahrezeugbau), which typically communist inspired title translates as: Industrial Association for Vehicle Construction.

Following the occupation, the entire assets of Auto Union AG were expropriated without compensation, and on 17 August 1948, the Chemnitz company was deleted from the commercial register, which had the effect of liquidating the former business. The remains of the Horch and Audi plants at Zwickau became the VEB (for ‘People Owned Enterprise’) Automobilwerk Zwickau, or AWZ. Now under East German control, the former Audi factory in Zwickau restarted assembly of its pre-war motorcars in 1949, these models being renamed IFA F8 and IFA F9, being similar to German DKW versions from the same design that also returned to production in the west.

From 1955 to 1958 old Horch factories produced the 6-cylinder Horch P240, quite a prestigious car at the time. The former plants of Horch and Audi from Zwickau were unified in 1958, to create a new IFA brand of Sachsenring within the East German corporation, with the former P240 model becoming renamed Sachsenring P240. As the Soviet administration inexplicably banned foreign exportation of the P240, the East German economic administration decided to stop production of the vehicle. IFA also produced the initial Trabant P-50 model from 1957.

From the pre-war Auto Union, only the DKW brand survived in post-war West Germany, and with loans from the Bavarian state government and Marshall Plan aid, a new Auto Union was launched at Ingolstadt on 3 September 1949, which is where the Hobby scooters were subsequently built.

Products continued DKW’s tradition of front-wheel drive vehicles with two-stroke engines, including manufacture of a sturdy 125cc motor cycle, and a DKW F89-Schnelllaster delivery van.

Many employees of the destroyed factories in Zwickau were employed at Ingolstadt to restart this production.

A former Rheinmetall gun factory at Düsseldorf was adopted as a further assembly facility after 1950, and introduced the company’s first post-war car as the DKW Meisterklasse F89P, available as a saloon, four-seater Karmann convertible, and van, based on the pre-war DKW F8 & F9 models.

Returning to our Hobby scooter, expecting to start and run this will obviously require turning on the fuel tap somewhere ... but unless you’re familiar with the machine, you’d probably never be able find it! Open the front door to the body shell, then fumble around in the top right of the cavity to find the lever, down for on, and over for reserve.

There’s an enrichment lever that pokes out through the door vents, so you can engage this with the door closed, though it may not require any further attention once you’ve switched it on, since the choke lifts off automatically as the throttle is opened.

A lawnmower-type recoil starter handle sits down on the left hand side between the end of the apron and back footrests and, pulling out, the steel cable extends out 30", so there shouldn’t be much issue with any operator ‘hitting the stop’.

Below the helmet/bag hook in the front apron, there’s a steering lock that would appear to effectively operate into the steering stem tube, which in conjunction with the secretly located petrol tap, would probably be considered top class security in such days before the invention of ignition keys.

Classed among the ‘Trials of Hercules’ would probably be pulling in the Hobby clutch lever, which is so heavy, that you try and pace yourself to junctions in the hope that you might, if possible, be able to avoid hauling the brute in again!

The speedo reading proved fairly accurate, and best on flat paced up to 35. With Hobby being no lightweight, gravity possibly helped the downhill run make 37, and the following uphill climb never fell below 24mph before cresting the rise, however, all results were somewhat impaired by faltering running that might be attributed to some restriction in the fuel supply.

Period tests generally quoted 40mph performance.

The front brake doesn’t really appear to be a brake at all, it’s just a lever you can pull to no obvious purpose; and the foot pedal manages little more than any mild retarding effect, seemingly irrespective of how much pressure is applied.

If you ever might need an emergency stop, then the brakes on this Hobby are only going to take you to oblivion!

The ‘suspension’ didn’t suspend much, as these front forks tended to stick in compression and not come up again, after which the rider just receives a steady battering until they might (or not) decide to return. Any rear suspension benefit you may gain from the compression rubber swing-arm is pretty minimal, it seems more of a ‘delayed effect’ jolting system, so don’t be expecting much sympathy from the back end. Basically, bumps pretty much came down to just the rider and the foam seat!

Underway, riding Hobby was like sitting on a washing machine full of brick rubble, and running spin cycle! The CVT seemed to maintain the engine speed at constant max power, so there was always lots of frantic revving, rattling and vibrating going on, irrespective of whatever speed the bike was actually running. 15mph or 35mph, the engine was always angrily going at it just the same, and the only happy cruising speed seems to be stationary—basically the single time it’s not revving its nuts off. Only then does Hobby feel at ease, ticking over and going nowhere!

Lights are given as 6 Volt × 15/15 Watt headlamp, and 6 Volt × 2 Watt tail, but they could only be encouraged to emit a dull golden glow in the final combination of on-switch and dipper. All went off again when changing to main beam, and the horn only functioned with the lights on—so we concluded some wiring was slightly out of order. The cut-out button did work correctly, which was quite a relief when this finally stopped the engine.

Returning from the five-mile test run, we noticed the primary side louvres had vented out what appeared to be some fine rubber dust, and suspected the machine might have taken an inclination to start eating its own CVT belt. Thinking this indication might be tempting fate to try improving the running for a possible re-run, we decided to call it a day on any further testing. An obvious advantage of the CVT drive is that the small capacity and relatively low performance motor can be maintained running towards peak output at all speeds, so should give a reasonably good account of itself while accelerating, and under adverse conditions of headwinds, inclines, or pillion riding. Period tests often praised the scooter on these specific aspects, but Hobby is an angry and wearing machine to ride with all the constant revving. Given that our test bike was not the best representative example, and even allowing that if everything might have worked more properly, the machine still has no relaxing ride option, so for that reason, we really didn’t like it.

DKW Hobby production reportedly ran on to some 44,000 units by the end of 1957, before the model dropped from listings early in the following year. 1958 was a turning point for the company, seeing the return of Auto Union branding on a small model 1000 saloon car, and at the same time introduced a stylish SP coupé model, produced by Baur coach builders at Stuttgart. While returning social affluence meant demand for motor cars was on the up, the German motor cycle industry was inversely sliding into severe depression, so DKW two-wheeler production was split off, to merge with Victoria and Express and form the Zweirad Union.

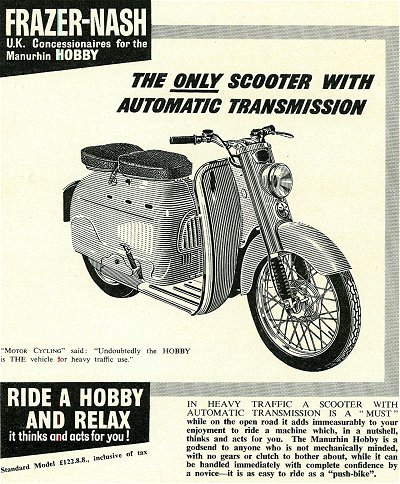

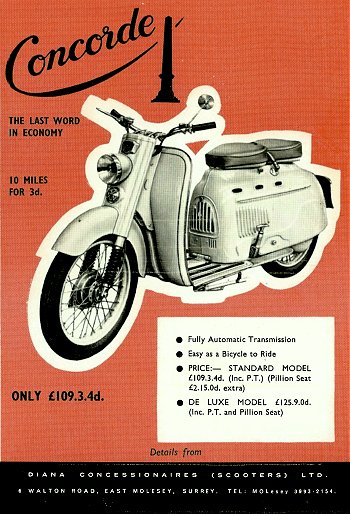

Tooling to manufacture the now discontinued Hobby Scooter was licensed out to Manurhin France and production resumed at the Parisian company later in the year, with conversion to automatic clutch operation, and a few minor detail alterations.

Daimler Benz acquired 87% of Auto Union in 1959, effectively taking control of its motorcar manufacturing and implementing the creation of a new range of cars, to become the Audi F103, Audi 80, and Passat, which would lead to a group renaissance in later years. Meanwhile, on the cold side of the wall, the IFA badge slipped down in status to a secondary logo, and motor cycles branded MZ now came out through the doors of Motorradwerk Zschopau.

With general prosperity returning to Western Germany, and exports returning much needed currency through sales to the rest of Europe and North America, Daimler became increasingly worried that without further investment, Auto Union’s only market may become increasingly limited to its two-stroke products into impoverished East Germany, so they began selling its shares. With support from the West German government, these shares were taken up by the Volkswagen Group, which subsequently acquired the Ingolstadt factory with trademark rights of the Auto Union and Audi brands.

The ongoing Hobby scooter received some cosmetic adjustments during 1960, a name change to ‘Concorde’, and period road tests now reported 45mph performance. Production at Manurhin concluded in 1962.

Towards the middle of the 1960s, Volkswagen became increasingly concerned by the fading popularity of two-stroke engines, as customers were more attracted to cleaner four-stroke motors. In September 1965, the last DKW model F102 car got a four-stroke engine implanted and some front and rear styling changes.

Intent upon re-launching the Audi as an upper market brand, Volkswagen finally decided to drop DKW because of its historic ‘smoky two-stroke’ association, and engine makers Fichtel and Sachs took over the Zweirad Union, adding to their established labels of Hercules, Prior and Rabeneick.

In 1969 Auto Union became Audi NSU as it merged with NSU, ultimately becoming Audi in 1985.

The final DKW-badged machine was a Wankel-engined motor cycle, last sold in the late 1970s.

With the reunification of Germany, MZ was denationalised to private ownership on 18 December 1990. This new freedom however was only short lived, as the company passed into receivership in 1993, resulting in the ETZ motor cycle patent being sold, and further production of 251 and 301 models continued by the Turkish firm Kanuni, while the remaining company reformed as MuZ (Motorrad und Zweiradwerk—Motor cycle and Two-wheeler Factory).

MuZ was purchased by the Malaysian Hong Leong Corporation in 1996, and its ‘u’ dropped from the name three years later.

As two-stroke engines progressively fell from favour, four-stroke motor cycle models with Rotax and Yamaha engines were produced.

Following years of financial losses, the Malaysian backers announced withdrawal of their commercial support, and after 88 years of motor cycle production in the same town of Zschopau, the original DKW factory closed on 12 December 2008.

The old East German factory has subsequently re-opened as a nightclub—called MZWerk.

In March 2009 rights to the MZ brand were reportedly purchased back for some 4 to 5 million Euros in re-finance from the Hong Leong Group. There are rumours of another MZ return...

Next—The ‘oddball’ third feature continues skirting the borders of our general small capacity brief with another ‘marginal’. We did an incidental road test and photoshoot on this 50cc motor cycle during summer 2010 and, since the notes are now older than anything else lined up for this slot, we figure some folks may enjoy A Sporting Chance with this little bike in the coming season.

Several other interesting oddities already appear to be lining up for the year ahead, so it looks as if the oddball third feature may well continue in its established theme for a while yet.

[Text and photos © 2011 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

The DKW third feature came about as a result of meeting its owner at the EACC Duloe Daffodil Dash in March 2010.

We got talking, as you do, and there seemed to be a couple of interesting opportunities among his collection, so we arranged to access the machines.

Features on small capacity scooters like the Hobby have dual appeal, since there’s the strong possibility of franchising such articles out to the Vintage Motor Scooter Club magazine. We’ve run several features in the past with the VMSC: Olympian Chariot on the Mercury Hermes back in May 2006, Popular Choice on the Dunkley Popular in January 2007, and Stella Motor Scooter Co just last year. With Hobby owner John Truluck being connected to both groups, availability of the little DKW scooter offered the chance of a double whammy article, so encouraged us to move the feature toward publication ASAP.

Mercury Hermes, Dunkley Popular and Stella Motor Scooter

What wasn’t appreciated at the time of the road test and photoshoot, was the complexity of the associated company connections that turned up in the subsequent research. It’s always a difficult decision: how much to include? While it’s always easy to edit these options out and just stick to the main direct facts (which many mainstream publications would generally do), we think that all the peripheral stuff is often what makes these things more interesting—so why cut out the best bits?

So, we ended up again with another hefty feature, but believe it’s better to make the most of our opportunities, since we may not count on many more returns to DKW.

With the Hobby at Peterborough, this involved a bit of a gas burning drive to collect and return the machine, but the journeys were somewhat compensated for by collecting a different second vehicle for another feature at the same time—you might say, two for the price of one. Got to be a bargain!

The split fuel costs probably meant the article cost around £25 to produce, and sponsorship was credited to Paul Efreme of the EACC Essex ‘Chapter’, which now seems to be attracting more county member turnouts at events than it ever used to manage in former days under the miserable old autocycle club.