Before the Second World War, Enzo Mengoli began learning his trade at the Cicli Busi workshops in Athos, Bologna, which was building racing bicycle frames for various brands. By the advent of micromotors in 1940, Enzo had graduated to working directly with Busi himself in the preparation of frames to take various makes of engines for the new cyclomotori and scooters. Resuming work after the war, Cicli Busi was renamed as Officine Meccaniche Busi as the business began to develop complete motorettes, the first being the Nettunia (Neptune) brand in 1947, initially designed for the Ducati Cucciolo but later going on to produce sporty two-stroke, four-speed motor cycles with 125 and 160cc engines.

Meanwhile, Mengoli had left Busi to found his own workshop business at Via Emilia Levante 158 producing frames and suspensions for motorised vehicles under an agreement with Amedeo Rocca, owner of O.Me.S (Specialised Mechanical Workshop). After presenting two Moto Mengoli (a 175 Turismo ohc four-stroke engine, and a conventional economy 125 two-stroke) at the Milan Motor Show in December 1952, Mengoli decided to abandon the project in the New Year and sold his machinery and patents to his colleague Angelo Zanasi, who already managed another nearby motor cycle workshop at Via Melloni 3, Monteveglio, Bologna.

Zanasi was speculating on the increasing demand for light motor cycles and mopeds, and the relative bureaucratic simplicity of homologating mopeds and motor cycles designed and built in small batch series. Production was planned to combine his own-made parts with bought-in proprietary components. In February 1953 Zanasi changed his business name to Officina Meccanica Montaggio Motoleggere Moto Meteora, and registered the brand of Moto Meteora in prepartion for starting the manufacture of motor cycles.

The first model was rushed into production and presented in April 1953 as a development of Mengoli’s Turismo O.Me.S 175cc ohc engine with four-speed gearbox, rated at 8.5bhp@5,800rpm for 95km/h (59mph).

A pilot batch of just 30 bikes was built, but proved unsuccessful because of the unreliability of the underdeveloped and under-tested engine.

In 1955 a new Meteora TS 125cc bike was produced, along with a 75cc motor cycle and other moped models, all fitted with two-stroke Franco Morini Bologna engines. Sales of these models increased steadily to the point of requiring more space so, in 1956, the company moved to Via San Mamolo 154. The move led to increasing the production volume of models and introducing further variants. Smaller capacity machines were proving particularly popular using FBM and NSU engines for mopeds and mini-scooters. A small Meteora motorcar with Morini Franco engine was also produced.

The range expanded further in 1957 with the introduction of a 150cc Minarelli-engined motor cycle.

During 1957, Zanasi became ill (dying later in the same year), and transferred the workshop and its management to Signora Isora Negri, who was an existing employee of the company.

The production of existing models continued as well as the continuing design of new ones, from the most basic Kalimero utility moped with rigid frame and Morini Franco motor in 1962, to refreshing the Meteora 150cc motor cycle with an updated engine. Beyond machines for practical transport and sport styles, new recreational off-road models also began to appear.

From the end of the 1950s and into the 60s, small batches of innumerable types were produced, often with just general descriptive names like Luxury, Sport, Super Sprint and Tourism, or even without any model name at all! As was often the case for small batch productions, the model names were often re-used several times, and together with machines ‘built to special order at customer request’, it creates a confusing situation in trying to assess the numbers of specific models built and, for dating purposes, identifying the production numbers.

Meteora also assembled three-wheeled microcars and moto-trikes using NSU engines in the 1960s.

So, our first ‘bike of the day’ is a 1962 Moto Meteora Super Sprint kick-start 50cc sports motor cycle with a Morini Franco Motori four-speed foot-change motor on an alloy rocking-pedal shift, forward & down for first, then three back for second, third, & fourth; neutral is between first & second, and as many false neutrals as you can find along the way.

Iron cylinder, alloy head, Dell’orto UA16S cross-slide carburettor with bell-mouth intake, and Sito racing expansion exhaust—it’s called a silencer, but it doesn’t!

It’s fitted with a new 36-tooth rear sprocket, and the 13-tooth front sprocket looks about as large as you might comfortably fit, so we wonder if this bike might be high geared for top speed?

Chrome 19-inch Radelli rims on nice Grimeca alloy hubs, 110mm rear and 100mm front with single-leading brake plate, and 2.00 Continental tyres. The telescopic forks are neat too, with smartly finished polished alloy shrouds on the steel bottom legs, and clip-on handlebars below the top yoke, furnished with polished alloy Domino controls and chrome levers.

The CEV headlamp is powered from the Dansi mag-set, and a Cronos speedo is marked up to 80km/h.

The chassis is a conventional single down tube spine frame with a popular proprietary period rounded tank and toolbox set, and NISA. humpback dual sports saddle, though no rear footrests, so maybe less intended for a passenger, and more for the rider to ‘tuck down to the job’.

The rear mudguard has deeper practical sides than the front guard, which has a closer wheel gap to make it more weather effective.

The chain guard style seems suitable enough to match the bike, though it appears to be too long, and with a welded front mount we do wonder if it might not be original? However, checking up to compare with other examples of the model, surprisingly the gawky chain guard does appear correct, so we can only presume that Meteora might have bought a job lot of ‘one size fits all’ proprietary chain guards.

Looking closer again, and the front footrest assembly is clearly a crudely welded and home-cooked affair, which makes us wonder if the four-speed foot-change motor could be a poorly executed conversion to what may have started as an earlier three-speed hand-change sports moped—but the kickstart, 4-speed, foot-change Super Sprint was a genuine model. All a bit of a mystery, now lost in the mists of its own history.

The gold and blue paintwork with white coach line is a tasteful combination to a mostly smartly restored machine with a very classy look. The period grease forks came as undamped, and it’s wearing the correct ADE Italy undamped rear spring units, but there’s just a few details that let it down if you look a little closer.

The centre-stand looks as if it’s had the saggy ‘chip shop’ treatment, been repaired prior to the paint restoration, then further welded afterwards, which has burnt the paint.

On the plus side, the ‘ring’ cable guide welded to the frame down tube in front of the cylinder head is such a neat detail, with another ‘ring’ on the right-hand fork shroud for the front brake cable.

The switchgear, wiring, and cabling is so tidy, and the horn invisibly mounted off the bottom yoke and tucked behind the headlamp—horns don’t need to be seen, only heard!

The fuel tap is located on the right-hand rear of the tank: off–on–res; click in the cross-slide choke from the left-hind side, flood up the float chamber … and we’d better remove that ‘bung’ from the bellmouth intake while we’re here (and put it in your pocket for later).

The motor fires up after a couple of kicks, but we don’t know the routine for this tuned and temperamental boy racer. How much choke? How much flooding? When to open the throttle? So after it’s died out a couple of times, we push start and coax on the throttle until it gets the message and the engine warms to run clear.

Hmmm, that motor sounds suspiciously angry?

Pulling away down the road on a pre-test ride, we work up through the gears, and discover a couple of false neutrals along the way (yeah, that’s a neutral between every gear).

Working the bike up to speed in top gear, the exhaust is predictably very noisy with the usual gulping induction roar every time the throttle is opened. The motor felt to be prematurely over-revving from seemingly too low gearing, but this was probably an early impression of other problems to come. The highest indication we got to on the speedometer was 60km/h (37mph), which was quite as much as we dared, because the engine felt worryingly harsh and angry with associated vibrations (suspected slack in the big-end bearing).

We didn’t want to try running this motor any faster due to concerns of possible terminal damage. Yes, it really was that bad, and never even made it to the track!

In 1967 the company passed into the hands of Franco Bonfiglioli (son of the previous owner Isora Negri), who moved the business to Riale di Zola Predosa, in via Risorgimento 88, and resumed the building of more Morini Franco powered machines including the Arrow, Mini Sebring, Minimet, Gim Cross 50, Cross 5M with radial-fin Turbo Star engine, as well as the Meeting moped in the style of the Piaggio Ciao, and mini-bike models.

By 1975 a sales crisis in the motor cycling sector was beginning to bite, and many of the traditional smaller players were being swallowed up by larger Italian national or foreign companies. The situation led Moto Meteora to reduce its production and to suspend research and development of new products, which in the case of small series production costs were now exceeding the income. In order to supplement its own reduced production, Meteora formed an agreement with Motobécane to build lightweights for the Italian, American, French, and German export markets, constructing some 15,000 machines up to 1980. Following a further transfer to Monteveglio, Meteora ceased producing machines under their own brand in 1980, resorting to subcontract assembly and supply of parts to other companies including Malaguti, Malanca, and briefly to Moto Villa who ceased trading later in the year.

In 1981 Honda agreed with Meteora to the assembly of 400cc to 1,100cc motor cycles for the European market utilising its Bologna factories, which at this time were underemployed and close to complete disuse.

So Meteora continued into the 1980s by assembling components from Japan, preparing and testing the bikes for putting on the road, utilising the technical resources and capabilities of its experienced staff, up until the definitive closure of the Bolognese plants in 1985.

The company however still continued as Moto Meteora di Franco Bonfiglioli, and moved again to Zola Predosa, in Via Mazzini 21/1, working mainly as a subcontract assembler for a period, building LEM motos and the Beta Minimoto since 2001, building mopeds and making mechanical components. The Moto Meteora trademark is still owned by the business, though currently unused.

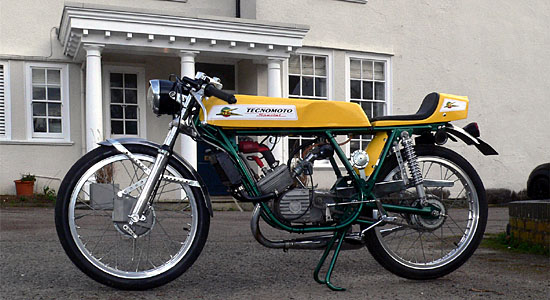

As well as the exotic Meteora, we have another more familiar slice of exotica … remarkably, another Tecnomoto!

We got really lucky securing our first Tecnomoto Special-50 model for our second Track Day ’70s feature in July 2017, and we could never imagine that we might get a second Tecnomoto for our fourth Track Day feature in April 2020, and now we have our third Tecnomoto, which maybe our most remarkable example to date.

Wearing frame serial ☆4006☆, this yellow-finish machine is dated much earlier at 1970, in comparison to the blue and silver 1973 ones we featured in the two previous articles.

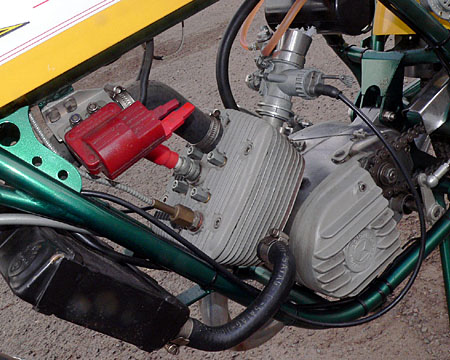

Our previous two Tecnomotos had the later angular case FM4R TurboStar motors, but this earlier yellow machine has the earlier round-case four-speed motor … and it’s experienced some remarkable modifications!

Straight away we note this is another twin-tap version at each side toward the back. The forward position tap is appreciably more difficult to access, since it’s quite obstructed by the frame brace.

The motor is fitted with a modern Malossi sports water-cooled top-end plumbed to an FIM radiator! There’s a Simonini vented dry clutch set with a cast alloy finned primary cover and matching Simonini cast alloy finned mag cover, behind which is a Spanish Motoplat Electronico ignition set, which doesn’t seen to deliver any generator power, because neither the CEV headlamp, Catalux FR tail lamp or horn apparently work—so maybe they’re just for show? Carburation is by a Dell’orto UB20S cross-slide with a bellmouth intake, and the motor exhausts though a 34mm downpipe with chrome plated straight-through race expansion pipe. It looks pretty impressive!

The Tecnomoto frame shows all the expected top quality fittings that characterised this breed, a widely spaced twin-tube frame designed for maximum rigidity, 30mm Ceriani forks with alloy legs and alloy yolks, and period twin rear shocks.

The 120mm front hub is fitted with two single-leading alloy air scoop brake plates, one each side, which means two cables coming off the right hand brake lever. The 110mm rear hub wears a standard single-leading rear brake plate, with both hubs laced into what look like Borani alloy gulley rims (though unmarked), shod with 2.25–18 tyres, and covered by stainless steel mudguards.

It sure looks an awesome bike, and now we’ve got to figure out how to get it to go…

Turn on a fuel tap, press in the slide choke, and flood the carb with the float chamber button … though it seems the kick-start is going to foul the rear brake lever?

We then notice that the foot-rest unscrews, and removing that allows the brake lever to be turned while still attached to its cable, so it then clears the kick-start. A few kicks, and the motor fires up for a test start, but initially seems to require constant blipping of the throttle and frequent re-flooding to prevent the motor from dying out. This situation also seems impractical for prospects of refitting the footrest and rear brake pedal.

After running the bike in the garage and getting deafened and smoked out for some five minutes, we decide the situation requires some sort of Plan B, so we shut down to have a think about it.

Plan B is to bump start the bike, which would allow the gear lever to remain fixed, and we can keep re-flooding as required and control the slide choke to keep the engine running till it warms up enough to run without enrichment. Trying a bump in third gear works surprisingly well, as the motor readily fires up, so clutch in, switch back down to neutral, then play the warming-up game. The exhaust still produces a lot of offensive noise in the open air, and particularly so because we have to keep blipping the throttle to keep the engine going. The motor still seems to fade if the choke slide is lifted off, so we’re resolved to just keep it running and monitor the water temperature gauge towards looking for some point where we might be able to clear the choke. We run up and down the drive a few times to get a feel of the riding position and again try without choke, but still no luck.

Although the bike is UK registered, the sheer volume of exhaust and induction noise is so loud that surely no-one could practically ride it on the road without getting pulled.

After a while longer we just resign ourselves that it’s time to load up and take it down the track then just run it around until it gets properly hot, and hope for the best.

So at the track and all kitted out, we just try a couple of light prods at the kick-start, and it fires up right after just a couple of short jabs, though the kick-start does get tangled up underneath the foot-brake lever; but then we find we can just push the footbrake down, which releases the kick-starter to spring back up again—duh! Mount up and cruise around the circuit a couple of laps with the choke on, watching the temperature gauge steadily creeping up as the bike is pulling under load now.

How hot might be hot enough to expect it to perform right? Around 80°C we started opening up, snapping off the choke, and trying for faster laps, but the motor stubbornly refused to run cleanly which dramatically reduced its obvious potential.

Two laps later and we’ve worked up to 120 on the Nuova Didoni dial, but that’s just degrees C, not mph. There still seems to be a limiting rev break-up, which effectively puts a ceiling on the top speed. It’s hard to put a finger on quite what the problem is, maybe some carburation issue because it won’t run cleanly without choke at lower speed, but won’t rev cleanly at higher speed with the choke off because of some sort of ignition breakdown. This might be some problem with the Motoplat electronic ignition, or something as simple as a sick spark plug. Whatever the cause of these problems, it’s going to take a lot of sorting out, because it needs a systematic going through, and actually riding under load to work through the troubles.

These issues aren’t anything that can be resolved by just revving it up on the stand, because that tells you nothing, which is probably why it is what it is today. Our best paced speed around the circuit was clocked at 42mph at full throttle, on the long and light downhill sweep around the back curve, but held back by rev break-up. With track time running out, and nothing more we could achieve here, it’s time to pack up and go home. Suspension and handling were great, good on the turns, steady on the straight, Tecnomoto made a really good chassis and they’re just spot-on every time. The brakes felt effective, though the low speed achieved meant they weren’t really worked very hard. The front brake demanded a firm grip to become effective, though that’s an absolutely normal situation for twin brake.

Our next segment of time begins in the Italian city of Modena around 1959, where the brothers Edoardo and Ercole Po opened a workshop together, specialising in the repair and sale of bicycles and mopeds. Given the popularity of mopeds at this time, Edoardo Po thought to begin construction of their own mopeds and light motor cycles by assembling frames using proprietary engines and components produced by other companies. Vittorio Minarelli also offered a strong incentive to help establish the new enterprise, with an offer to provide engines on a ‘pay only after sale’ contract.

Though the brothers began their workshop together, Edoardo Po registered the company on his own, which he titled Romeo dei Frattelli Po, the Romeo name being chosen to compliment the name of the Giulietta brand made in Vincenza by a division of the Peripoli company.

The first three Romeo models, Superturismo, Italia, and Zeta were all fitted with Minarelli engines, and offered for sale in 1961.

Due to a high demand for both economical mopeds and sports 50s, the Romeo became an immediate local success, so production volumes were quickly increased to seize the opportunity, while sales were also expanded by wider area coverage. New models to further expand the range included the popular Sports Sprint, Sprint Supersport, and Sprint Veloce mopeds, which Romeo had cleverly chosen to echo prestigious names previously used by famous Alfa Romeo motor sport models. Sales were further increased when Romeo arranged a promotional incentive to free-deliver their bikes directly to dealers inclusive in the sale price.

The moped boom in the second half of the ’60s delivered a tremendous surge in the sales of mopeds and sports-50s as they became very popular and fashionable with younger riders.

In 1968 Romeo designed its first Fujihama junior motocross mini-motor cycle built with a lightweight single-downtube frame and an upgraded engine, though initially resisted by Edoardo Po due to safety concerns about young riders, but other manufacturers were already selling similar models, so the Fujihama was subsequently launched, and quickly became a craze for youngsters of the time.

Romeo further went on to resolve the structural problems of creating a lightweight dual-cradle chassis using minimalist tubing in 1970, and presented three new models for the 1971 season, Monster (touring & sports), and Scorpion Cross (both available with Minarelli P4 and P6 engines), and a Pedrito (mini-bike)”. These also proved very popular and the factory was on overtime and night shifts again to keep up with orders.

So, we’ve reached the point at which our test machine enters the stage, a Romeo Corsa dated 1972.

This is obviously NOT a commuter bike, and what a surprise, Corsa is another long-standing sports car name used by Alfa Romeo!

The frame is one of the twin-downtube cradle chassis with twin top rails (it’s like a miniature version of a Norton featherbed wideline frame), with swing-arm rear suspension and CRAI damped spring units.

Up front the telescopic front forks have S&F alloy yokes, and clip-ons below the top yoke.

The bike measures 72 inches nose to tail, and the fuel tank is 21 inches long, which naturally presents the rider with a crouched position. The fuel cap is three quarters of the way down the tank towards the saddle end and the tiny lever fuel tap is tucked away under the rear right of the tank, just off–on, though this may not be the original tap.

The Romeo ‘humpback’ sport saddle looks as if it isn’t pretending to accommodate a passenger, and there are no rear footrests, so it appears the bike was primarily intended as a single-seat sportster, and just trying out the riding position—that’s easy to believe!

There are rectangular ‘Corsa’ panels each side of the frame, but these are just open-backed cosmetic trims, and not functional as toolboxes in any way. Painted dark red with graphic decals and red, white, & green Italian flag trim tape, there’s nothing discrete about the way this bike looks—it’s an unsubtle boy racer.

The rider’s footrests are bare and brutal folding steel pegs, and it’s usually better to get into the habit of folding up the right-hand peg whenever you stop, because failure to raise the peg before attempting to start will deliver a painful reminder halfway down the kick-start stroke.

Stainless mudguards cover both wheels, with the rear tyre sized 2.75–17 on a 120mm diameter steel rear hub with steel brake plate and rod brake linkage. The rear sprocket is only 26-tooth, so is that standard, or has this bike been geared up? It does seem very small, we’ll have to wait and see.

The front tyre is 2.50–17 built on a double-sided steel front hub with 110mm diameter single leading alloy brake plates each side, complete with with air scoops—but these are just for show since the vents are blanked inside.

The 36-hole front rim is a chrome plated steel-gulley pattern, while the back rim is a Westrick (non-gulley) profile, so the front wheel is probably an upgrade replacement for the original front wheel with single-sided hub.

Two cables go from the front brake lever, operating each front brake, with the lever brackets welded to the clip-ons, which gives a clean and tidy look, and fitted with sporty looking alloy levers.

There’s no speedo in the Veralux headlamp (just a blanking plate), while the Aprilia tail light is little more than a cheap plastic pretence at illumination, and though there’s a horn button on the switch—we failed to even find a horn!

But this Corsa is absolutely all about the motor—the incredible P6, which Minarelli introduced in 1969, with six foot-change gears! This looks to be one of the early motors, with iron cylinder and big-fin alloy head, 38.8mm bore × 42mm stroke for 49.6cc, with 12:1 compression ratio, and rated 6.8bhp @ 9,000rpm on a standard Dell’orto SHA14/14 carb … except this has a Dell’orto PHBL20AS with lever choke fitted.

OK, saddle up, and try to find some sort of comfortable riding position, but for anyone over 5'4", over 7¼ stone, and over 18, there doesn’t seem to be one (and we fail on every count). The riding position is stretched out, but hunched up, and not designed for comfort, as the footrests are situated in a forward position.

Turn on the fuel tap, then flip the choke trigger on the Dell’orto carb to lock it on in the upright position for full choke. It generally seems necessary to start on the choke unless the motor is still hot, when a couple of jabs at the kick-start usually achieves the desired result, then leave to warm the engine a while since a premature switch-off causes the engine to die out, until we’re fairly hopeful we can coax the motor to continue by blipping the twist-grip.

With a big-bore 35mm downpipe into one-piece Lafranconi exhaust expansion system, the tailpipe issues an offensive crack on tickover, which gets even angrier in response to the throttle, and it’s joined by a loud intake draw from the open bellmouth. We’ve not even got the bike into gear at this stage, and it’s already obvious that Romeo is not going to be a discrete machine to test ride around town, so straight down to the track for this one.

After the same long warm up sequence on choke, clutch, click down for first, throttle on, and we’re away. As you click up through the seemingly endless gears (shift pattern one-down, five-up), the induction roars in even louder gulps under load as the throttle opens up to complement the violent snarl of the expansion pipe, which delivers a constant sequence of noisy throttle bursts as you go up and down the gearbox—it’s very anti-social.

The acceleration is pretty impressive up through the gears, and while each shift-click selects pretty well, our progress is limited by having to struggle through throttle flat spots, which become more obvious in the higher ratios. As we get into sixth the motor doesn’t produce enough power to pull the gear, and drops pace along the flat until you have to cog back down to fifth and nail the throttle wide open again to try and claw more speed, then lose it again when you retry in sixth.

The highest speed paced around the track was clocked at 46mph in top gear on a full throttle run on the long and light downhill sweep around the back curve, but the engine was obviously not producing enough power to deliver a representative result.

It’s either over-geared or underpowered, but the overly long choke-on warm-up period was some indication that the carb is under-jetted. It’d probably figure that the ‘bolt-on goodie’, big-bore 20mm carb has just been fitted as it came, and straight out of the box, and nobody has put in the effort to set it up properly. Fitting the correct bigger main jet could transform the way this machine goes, because it certainly has the potential to perform a lot better once the motor can be coaxed to produce more power at revs.

The only way to do this is to test ride the bike in gear and under load. Just revving it up in neutral tells you nothing.

The front brake feels as if it has a heavy hand lever action, but the mechanics of having two front brakes means you will need to pull on the front lever twice as hard. The twin front brake can offer better stopping, and with the Corsa, you might be glad of that occasionally if the bike was performing as it should. Riding modern bikes with small but powerful light action hydraulic disc brakes makes you appreciate how hard you have to pull on big drum brakes for a usually lesser braking performance.

In 1973, Romeo’s first ‘Tuboni’ frame Tentation model was the pilot model of a successful series, which would remain in production until the 1990s with popular models GL 4 Flash and GTO. Romeo was really late to the ‘Tuboni’ party on this occasion however, since the tank-in-tube-frame design was jointly credited to Oscar at Bologna in the North East, and Tecnomoto at Vignolo in the North West in 1968. A whole load of other manufacturers had already jumped on this bandwagon by the time Romeo arrived, but that didn’t matter because it was a popular style for 20 years, so everybody got their money’s worth out of the design, and they all looked pretty similar because they were all based on Verlicchi frames (see MZV article if you want more Tuboni).

The sons of Edoardo Po, Ermanno and Adriano, had joined the company in the mid ’70s and wished to modernise the name. The initial plan was to rename the company Motrom (Motori Romeo), but as that was considered confusingly similar to Motom, a Milanese motor cycle firm which had ceased production in 1971. So in 1976 the name Motron was adopted instead (not so confusing at all?).

For a while exactly the same models were sold under both Romeo and Motron brands, only distinguishable by the paint scheme and decals.

Motron ceased production in 2000, but still continues as a label under the Austrian KSR group importers with brands Brixton Motorcycles, Motron Motorcycles, Malaguti and Lambretta (which all look like Chinese pick-and-mix to us).