The 1960s naturally lead into the 1970s, and we’re back at the track to see what the new decade might bring with another triple selection of exotic Italian circuit racers. When IceniCAM got offered access to a whole load of interesting and exotic Italian sports 50s, we decided to have a bit of a track day with them as a change from the usual road test. The private short-circuit track we’re using again doesn’t involve any of the usual hill sections of our normal road tests, but that’s OK because of the nature of these machines; the only real relevance is mostly how they perform on the flat around a racecourse. All these bikes started life as road-going 50cc sports motor cycles (not mopeds) and, at the time they were originally sold onto the Italian market, would have been performance-regulated for highway compliance. They’ve subsequently received varying degrees of tuning and modification, involving much bigger carburettors, raised engine compression ratios, cylinder porting and exhaust changes, altered riding positions, and changed gearing. Any memory of the classic sports styles of the 1960s may suddenly start looking tame and sedate when compared to their full-blown and outrageous counterparts of the ’70s—it’s like comparing a biplane to a Star Wars X-wing fighter!

We start again with what might appear to be our oldest machine (from at least some components). The Series-1 Benelli Sprint launched our last Track Day ’60s feature and, if that felt like going right in at the deep end, then welcome to the new space-age nightmare…

Umberto Testi opened his bicycle shop in Bologna in 1934, from which the Testi ‘Technique with Fantasy’ company was founded in 1936 as a manufacturer of racing bicycles. Arnoldo Benfenati won the amateur track title at the 1947 World Championship in Paris riding a U Testi track bike, and also won a Silver medal at the 1948 London Olympics in the men’s 4,000 metres team pursuit. While Umberto’s passion remained in racing cycles, the company was also attracted by the developing demand for economy motorised transport after World War II and, with his son Erio, in 1949 produced a 98cc autocycle and a 48cc moped, both powered by Sachs engines. It quickly became obvious that the greater potential was in the new 50cc capacity so, by 1951, the autocycle had been dropped in favour of mopeds, mofas and mini-scooters, but these were also joined by a 147cc Sachs powered motor cycle. Home built Italian Demm and FB–Minarelli engines subsequently replaced the German Sachs motors, and Testi entered into a co-operative relationship with proprietary engine builder Demm in 1953, building frames for Demm engines until 1956, when Demm began producing its own frames, and Umberto Testi went bankrupt.

Umberto and Erio resumed production in 1958, with a new company now registered as Velomotor Testi, using Minarelli engines, and also building ‘branded’ machines for trade customers (Kerry Capitano models in the UK being a typical example). Beyond basic 50cc mopeds, models also included some larger capacity light motor cycles, tri-porter carriers, scooterettes, 50cc street sports Grand Prix, and in 1961 the first 50cc ‘Trail King’ off-road motor cycles. All-terrain lightweight motor cycles became popularly established and exported to America as 50 and 90cc Trail King, Weekend Cross, and Carabo models.

Another important model, built in various versions since 1969, was the Testi Champion, initially fitted with a Minarelli P4 motor, but also becoming available in a six-speed P6SS (Super Sports) version from 1971. It’s around this point that our first test machine comes in, which is seemingly built up from selected components… Arrrghh! Where do we even start with this?

The old Italian Log Book indicates the Testi frame as dating from 1966, though we’re unsure as to how that may be, since as far as we can tell, the twin-downtube cradle frame with reinforcing gussets at junctions didn’t seem to first appear until 1968? The tape measures just 65 inches long tip to tail, while its highest point is the seat fastback at just 32 inches and seat height 27 inches. It’s certainly a small bike and weighs in at just 4st 4lb (27kg) front, and 4st 13lb (31kg) rear, so all-up just 129lb or 58kg.

The rear tyre is 3.25–16 and front 2.50–16, on chrome steel Westwood pattern rims with Grimeca full width alloy hubs, both single sided, single leading brakes 110mm front and rear. The alloy front brake plate really looks the part with intake & outlet venting, but its brake proves completely useless in operation. You can pull the front brake lever up to the grip, and just push the bike along—hopeless!

The angular Minarelli P4 engine block appears to date within the 1970s, but the huge radial fin top-end is an even later sport kit fitted with an earlier 19mm cross-slide Dell’orto carburettor. The bike is basically a parts-bin special, and it’s pretty difficult to figure quite what may remain of the original machine (if anything does at all?)

By the special machined channels down through the cylinder barrel and head fins to clear the frame downtubes, it’s plain to see this top end could never have been an original fitment to the assembly, needing this dramatic conversion to adapt the engine into this frame—it almost looks as if the engine has grown around the frame, or maybe the frame has grown through the engine…

The fuel tank is Gitane, and the front forks have 25mm stanchions with steel sliding legs. The alloy yokes are in as-cast finish, not dressed or fine polished like Ceriani yokes, indicating the Testi is built on a tighter budget.

There are 8-inch rear-set linkages to the footbrake & gear-change, but the kick-start fouls the right-hand foot peg halfway down its stroke, and might benefit from a folding peg—if only you felt you might ever be able to start it with the kick-start…

We didn’t even bother trying, we just went straight for the bump start—though we didn’t have any more success with that!

After a lot of pushing the bike up and down the road, with no more result than occasional sporadic firing, we figured the motor bottom end had over-fuelled because the petrol tap had been left on since before we’d even collected the bike, and with the downdraft carburetter, the resultant flooding had only one place to go (does this seem like a familiar story, re: Malanca Nicky?) With a lot of tell-tale black petroil dripping from the exhaust joints, remove the spark plug, open the air slide, and vent out the motor with compressed air. Clean the spark plug and have another go, at which we got it to run briefly, before it fuelled-up again, so we vent the motor again.

It takes us ages to get the wretched motor to finally catch on a bump start, so we hold it on light throttle to warm up as the engine clears, while the tailpipe already issues a fierce crackle that tells us straightaway that it’s going to be very loud and angry for waking it up. When the running seems to have settled down we can start blipping the throttle to purge the motor, whereupon our Minarelli reveals itself to be a howling rev-monster that wants to be held on the boil, or it just flattens out because the motor tuning doesn’t seem to generate any torque. Gear pattern is 1-down, 3-up with a light shift and positive selection, though the pedal requires a long motion on the lever because of the rear-set linkage.

As the motor revs climb onto the porting, a loud induction roar kicks in from the carburetter intake, which echoes and resonates between houses down the street. Within a second the revs are over the edge and you need to change up, then try to balance the banshee revs to maximum acceleration again in the next gear. It all sounds very dramatic, but probably isn’t efficient unless you’re an accomplished racer. The straight-through expansion pipe produces a savage crackle at low revs, which turns to a furious, ear-splitting snarl as the revs pick up. How can a 50cc make so much noise? There’s no practical way you could ever ride this on the road—you’d get arrested!

Having now managed to get the bike going at the workshops, we continue the action down at the track… Ripping open the throttle in the lower gears delivers devastating acceleration … you really can’t believe this is 50cc, it seems to perform more like a fiery 125! Impact of the performance seems to be enhanced by the deafening crackle from the exhaust and howling induction roar as the carburetter hoovers in hungry gulps of atmosphere. The whole package of this bike is really quite intimidating. Its looks, performance, and whole demeanour are so demonstrably aggressive—it’s a really mean machine! On flat in still air clocked 56mph by satnav by the pace bike, with our CEV speedometer vaguely indicating just under 100km/h.

Our Testi was certainly fast and impressive, but in a 10-lap race, put your money on the Raleigh Runabout, because this highly strung Minarelli is surely going to break down. We managed about four miles on the track, before dropping down to second into the hairpin, then seemingly over-fueling the motor again when opening up from low revs after the turn, and spluttering out on the entrance to the next straight. Spectacularly exciting on the rare occasions we could get it briefly to work, but really not worth the hassle.

Testi exports in the late 1970s included Iran and France, which led to a collaboration with the French Gitane company, leading to marketing of models in France as Gitane–Testi, with assembly taking place at the workshops Micmo Machecoul in Département 44. The 1980s proved difficult times for the motor cycle trade in general, and particularly a number of moped manufacturers, who found demand for 50cc machines falling away, so the business re-structured as Micmo Purtroppo Testi and attempted to recover sales in building 125cc Easy Rider, Stroke, and Corsa 2000 motor cycle models, but that didn’t go so well either so they filed for bankruptcy in 1986. Micmo production was restarted in 1987 under the management of the World Trade Organisation, but this business was so far removed from the original Testi Company of Bologna, as to now be completely unrecognisable.

The Testi factory at 11A Via Parini 40069 Zola Predosa Bologna was listed as a manufacturer of motor cycles, scooters and sidecars until it finally seemed to have closed in 1993, and appears to remain out of use.

The story behind our second featured machine starts very similarly to the preceding tale of Testi…

In 1937, Olympic cyclist Marco Cimatti founded a small company in Bologna to produce bicycles. In 1949 the business moved to the village of Pioppe di Salvaro, about 30km from Bologna, to occupy a large and vacant old building that still showed un-repaired bombing damage from the war. Cimatti started moped production in 1950, making his own frames rather than buying them in from proprietary sources, and fitting engines from the newly established Austrian HMW Company, which had only started business the previous year. This gamble worked out well for Cimatti since the HMW quality was good, and the engines earned a sound reputation for reliability. Gran Sport 50cc motor cycles were produced as far back as 1955, and introduced a new Sprint twin-down tube cradle sport frame style at the Paris Salon in 1958, which was available with three-speed Morini–Franco engine or 2.5bhp HMW motor. In the early 1960s Zündapp engines were also built into Cimatti frames according to preference of the customer and market nationality, but HMW engine manufacture ended in 1962, which must have been a blow to Cimatti, since their motors had been fitted from the beginning of both companies, but these had become difficult times for the worldwide motor cycle trade, and many well known and established names were disappearing from several European countries.

However, as the competition began thinning, Cimatti was also fitting Minarelli engines, and seemed to be becoming one of the market winners, as it now started producing 100cc and 175cc Luxury Sports and Kaiman Cross motor cycles.

Between 1966 & 1968, Cimatti won the Italian 50cc Trials Championship three times, during which time its motor cycles were being sold through the Gambles chain of hardware stores across North America.

The early 1970s introduced two new 15bhp, 125cc motor cycle models, one for motocross competition with a five-speed gearbox, and the Ariete 5M for road use. City-Bike and Town-Bike commuter moped models were also sold throughout the 1970s as Cimatti’s son Enrico expanded the business to export products to the USA, France, Norway and Tunisia.

Our second ’70s racer is a Cimatti model S5 with a twin-tube, full cradle frame, and it wears distinctive reinforcing gussets at the forward junctions. The bike measures 68 inches long tip-to-tail, and weighs in at 4st 7lb front / 4st 10lb rear, so appears to be pretty well balanced.

The 25mm fork stanchions have ‘economy’ steel legs and alloy yokes, and mount a 110mm double-sided steel front hub with two single-leading 110mm Grimeca alloy air-scoop brakes, one on each side of the hub. The rear has a standard 100mm steel hub with single-leading steel brake plate and both ends mount 2.25–18 wheels & tyres covered by stainless steel mudguards. The Minarelli P4 motor has a cast iron cylinder with alloy head, and rocking-pedal heel & toe gearshift in 1-down / 3-up (back) change pattern. A Dell’orto PHB19mm carburettor feeds into the motor, while spent gas exits by an expansion chamber exhaust with a stubby little 4½-inch long, straight-through baffle fitted on the tailpipe—which really doesn’t look as if it’s going to quieten it down much! For starting: just turn on the fuel tap, lift the choke knob and turn to lock, a couple of kicks and the motor fires right up with a fierce crackle from the exhaust—yeah, that baffle was just a token…

We settle down to try and find a natural riding position with the mandatory clip-on handlebars, but there are no rear-sets, and the footrests remain in the standard location, so the riding position is somewhat uncomfortable when you’re tucked down on the tank—your knees are on your chest! This stance also makes back-changing with your heel particularly difficult, so you often have to resort to toeing the shift instead.

The Cimatti shows very easy and stable handling, and is almost certainly our best steering bike yet. You could confidently hold it on throttle with just one-handed steering, running right down the straight and through the bends. A bumpy section coming out of one of the turns where the surface was breaking up slightly still didn’t cause any concern riding single-handed, and the bike tucks neatly around the hairpin with no fuss at all. This S5 certainly handles very well, despite the cramped riding position. When we give it the beans, the motor picks up revs quickly enough through the gears, but seems to tail out toward the upper range. Maybe it wants a bigger main jet or a higher compression ratio to extend its urge, but there’s no doubt it felt slightly short on top-end power compared to a very similar specification motor on the earlier ViVi SaS. The porting in these earlier Minarelli cast iron cylinders wasn’t as radical as the later alloy cylinder types, and you certainly compare the difference.

The headlamp on our S5 has no speedometer and is just closed by a blanking plate, so our progress around the course is clocked by the pace bike. Our Cimatti engine pulls up to a paced 45mph along the straight, then flattens out and sits there, unable to pull any more revs. A flat-out long and light downhill sweep around the back curve readily saw a pace of 50mph, but the S5 was undoubtedly the slowest of all our bikes so far.

Our pacer ‘commented’ on the piercing aggression of the fiery snarl ricocheting from the exhaust, describing the tone as ‘painful to follow’, and that ‘the noise police might be along any time to arrest us’…

Following the recent global oil crisis, in 1977 motor cycles were dropped to focus exclusively on the growing demand for fuel-economic vehicles. Garelli engines also started to be fitted to some moped models from 1982, but by this time Cimatti had got caught up in the developing industrial recession of the early 1980s; the collapse in business forced the company to close in 1984.

Last up is a Tecnomoto ‘Special’ model, which we actually went for as first pick of the various machines on offer when we started our Track Day double feature. The Tecnomoto would be our first choice, and for very good reasons…

The Bolognese brothers Vittorio and Giancarlo Pelegrini began with a business renting out bicycles in the Riviera resort of Romagna, then progressed to building mopeds on commission from other manufacturers. This led to an association with Negrini motor cycles at Savignano sul Panaro, Modena, before moving from Bologna to establish their own family run motor cycle business at Casa Di Vignola in the province of Modena. The Tecnomoto workshop started manufacturing children’s Mistralino TM50cc and TM80cc mini-motor cycles in 1968, and a folding ‘Junior’ mini-moped, all using Minarelli engines.

By the following year, the range was being by no fewer than seven models of ‘Personal’ and ‘Mio’ commuter mopeds and 50cc motor cycle variants, all appearing to be based on proprietary Verlicchi step-through frames. In 1969 Vittorio presented his first Squalo and Sports Special 50 & 60cc road bikes with special water-cooled competition engine kit options, and power outputs rated up 10.5bhp @ 12,000rpm.

The 1972 range listed: seven models of moped and 50cc sport motor cycles using mainly Morini–Franco engines, three 50cc Zündapp-engined Cross models, a Zündapp 125cc Cross motor cycle, and two 125cc Morini–Franco powered Cross and Regolarita motor cycles. A Paciughino Mini Cross motor cycle for 4–12 year olds with a 48cc Morini–Franco engine limited to 15km/h listed in 1973.

Tecnomoto Sports 50s were always specialist machines, and built only in limited numbers, using the best components available at the time. They weren’t built to a price, they were built to an exacting standard and the quality reflected in the cost…

Our machine is dated by its Italian registration book as 1973, and identified by frame number TMS .0438. Considering the Tecnomoto ‘Special’ model entered production in 1970, it’s plain to see from the number how exclusive these machines were, when only serial 438 had been reached in three years.

Many of the Italian motor cycle manufacturers built machines from selections of proprietary parts, and invariably only made particular components to fit the bikes together. Wheel hubs could come from a number of sources. Cheaper options would have been pressed-steel fabricated hubs, but Vittoria selected Grimeca, with a single leading 120mm full-width alloy rear hub on the rear. The front is also a Grimeca full-width alloy hub, but this is double-sided, with 110mm single leading brake plates on each side of the drum. The hubs are laced into San Remo alloy ‘gulley’ rims with stainless spokes, and shod with 2.25–18 tyres. Nice wheels demand nice forks, and these are Ceriani with alloy legs, alloy yokes, and 30mm stanchions, with 7-inch clip-on handlebars clamping the stanchions below the top yoke. Very few other sports-50 builders would fit forks of this gauge or quality.

Also, a number of the Italian motor cycle builders never went to the trouble of making their own frames! Frames could often be another proprietary item, constructed to the customer’s specification by a specialist frame builder, and Verlicchi would seem the most likely source for many of the full twin-tube frames, with widely spaced rails, which was a particularly rigid design they produced and adapted for many customers. The frame is supported by a study paddock-style roll-on centre stand, and fitted with twin-shock swing arm rear suspension.

With an all-up weight of 9st (57kg), its balance shows as 4st front / 5st rear, with a 25-inch saddle height and measuring 71 inches tip-to-tail.

The frame is topped with a 65cm long fibreglass tank and seat unit, which was made for the model, and is still in its original blue finish with metal flake sealed into a deep clear lacquer coat (other colours were available). There’s also a matching finish fibreglass trim in the frame forming the lower/front rear mudguard section. The engine is a Morini–Franco 4M/R TurboStar with 20cm/8-inch wide finned alloy cylinder, and radial finned alloy head, which certainly looks the part, and is fitted with a 19mm Dell’orto carburettor and 32mm exhaust into Lafranconi competition expansion box.

TurboStar engines were available in four-speed and five-speed versions, but this is a four-speed (1-down/3-up), and there’s a bit of a story as to how the Morini engine came to be fitted…

The Pellegrini brothers

When Tecnomoto produced the ‘Special’, Minarelli had just begun production of the new P6 six-speed motor, and the Pellegrinis very much fancied it for the ‘Special’. Having had a contract with Minarelli for engine supplies for their other Tecnomoto models, Vittoria was surprised to be told that all P6 motor production was already taken by the big volume builders like Testi and Fantic, and that there were no units spare.

So, the Pellegrinis went to Morini–Franco and asked if they could supply an equivalent six-speed motor? They couldn’t do a six, but they reportedly offered to squeeze a new 5-speed cluster into the TurboStar, so Tecnomoto went with that. While the Tecnomoto Special might seem as if it’s specified as a full-blown circuit racer—it’s actually not! This is a road bike! It comes standardly fitted with lights and a horn, a little round toolbox beneath the tank, and stainless-steel mudguards, though it doesn’t come with any speedometer fitted; with the speedometer socket blanked out in the headlamp, a speedometer set could be fitted as an accessory.

There are two fuel taps beneath the back of the tank, one for main tank and one for reserve, but we can’t figure out which is which, so we turn both on just to be sure.

Pull on the choke and turn to lock, then a couple of jabs on the kick-start and she readily fires up.

The expansion system with 210mm long × 12mm diameter tailpipe certainly produces a lot of anti-social noise, so we quickly drop the choke and blip the grip to clear the tubes—throttle response seems rather snappy (and very loud, this doesn’t seem like a road legal exhaust, and we very much doubt there’s any baffle in there).

With our pacer queuing on the circuit entry lane, we slide aboard and try to settle into the riding position that was seemingly intended for a diminutive 7-stone Latino jockey. The tank is a fair length, and the clip-ons are a way forward and down, so you naturally stretch out along the tank, then push your seat out to the fastback on the saddle, and fold your leg up and onto the rear-set to click into gear.

First proves a high bottom ratio, so requires a fair bit of revving and sliding in the clutch to get away. There’s relatively little torque, but it’s obviously not going to be tuned for that purpose. As revs pick up, the motor climbs onto the porting and accelerates very dramatically as the crackle from the tailpipe snarls to a howl. This sure is a very loud and angry machine! Shift up through the ratios while giving handfuls of throttle to get the feel of the bike, which feels fast, but is hard to gauge with no speedometer and the unfamiliar tucked-in racing position. Looking back, our pacer looks to have been taken by surprise by the acceleration of our 50 and is now making efforts to make up the lost ground. Our Tecnomoto Special just wound up to speed, and sat steady at 51mph on the flat in still air.

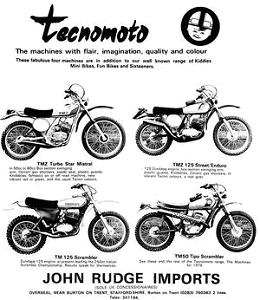

Various Tecnomoto TMZ models from 50cc to 125cc were being listed for 1974, and John Rudge Imports of Burton-on-Trent were advertising a selection of these machines for sale in the UK, so occasional examples can be found in Britain. Manufacturing of Tecnomoto motor cycles and mopeds ended in 1979, though the company continued as a family run motor cycle sales, repair and workshop business, until finally being closed down and sold off in 2016.