There are some tricky questions in today’s quiz, because very little information is available on the manufacturer concerned. In fact, the make is so obscure that it’s practically impossible to determine even when the company started, so all we can do is pick up from the earliest traceable reference, which somewhat strangely takes us to the USA.

MBI of Pennsauken, New Jersey began in 1964–65 as First American Bicizeta Inc, when the business started importing the Bicizeta motorized bicycle manufactured by Zanetti Motori in Bologna, Italy. The Bicizeta was basically a front-mounted 50cc cyclemotor with recoil starting and an automatic clutch with friction roller drive. This was mounted on a folding, step-through cycle frame, and delivered a sub-20mph performance.

Tuboni

Oscar College

Tecnomoto Personal GT

Peripoli Oxford

Negrini Harvard

Subsequently adopting the title of Motor Bike Imports Inc (MBI), the company contracted MZV of Bologna in 1968–69 to produce further mini-bikes and mini-cycles using the Zanetti engines, and sold these under Safari branding as ‘Scats’. In the early 1970s, MBI began importing MZV mopeds for sale as Safari, and also entered into a partnership with an Italian engineer to start its own bicycle manufacturing company, named Rovet. In 1975 Rovet made the Safari Rovet motorised cycle with a step-through rigid frame, and fitted with the same Zanetti front engine, producing 1bhp, for 19mph, which became DOT approved for street use in the US.

For 1975–76, MBI began to import other complete mopeds built by MZV, fitted with Minarelli V1 fan-cooled automatic engines, and sold as Safari Ridget (rigid rear frame), Safari Super (sprung rear frame), and Safari Super Extra (+ speedometer, extra trim, and a dual seat from mid-1977). In 1976, Rovet also manufactured the Safari Fox, which was another version of the Safari Rovet, with two thin crossbar tubes added to make it more like a stiffened ‘gents’ diamond frame.

New Safari/MZV models for 1978 had motor cycle style top-mounted tanks, with new model names suffixed with MT (for Motorcycle Tank), and these models proved more popular in the US than the step-through versions. The Safari Commando also introduced a sport model with a four-speed manual Minarelli P4 engine.

![]()

Before we get to our MZV Cambridge SS road test, your University Challenge starter for ten is quite how an Italian moped might ever become called a ‘Cambridge’ model? It does seem a little unlikely, doesn’t it? This sub-story requires an appreciation of a particular frame design called tubone, which came about from a need to reduce production costs by using the internal volume of the main frame tube as the fuel tank. Achieving this required a significant increase in the diameter of the tube in order to hold a practical amount of petrol.

The tubone design was evolved, seemingly simultaneously, on two sides of Italy, and is usually jointly credited to Oscar at Bologna in the North East, and Tecnomoto at Vignolo in the North West, both resulting in very similar models which were presented simultaneously. The large diameter main frame tube was formed in a step-through, U-shape for a unisex appeal, and was aimed at a popular demand for practical and economic transport among the young college demographic.

Oscar’s ‘Mister College’ model went on sale in 1968 as a four-speed development of its preceding ‘College’ single-speed auto model, and the new ‘sports’ version was an instant success among the educational fraternity. During the first decade of sales, this particular style of economic frame-tank moped became defined as ‘college’ type, and the various manufacturers that adopted the design took to naming their models with further educationally-related titles, like the Atala ‘Master’, MZV ‘Senior’, then famous university institutions like the Negrini ‘Harvard’, Peripoli ‘Oxford’, our MZV ‘Cambridge’, and the ‘Montreal’.

The term tubone was only originally used by the manufacturers that built the frames, but subsequently spread within the trade by the 1980s, and the earlier college-related model names became replaced with other more marketing driven models of the new times…

In the UK, the NVT Easy Rider would be a familiar example of a tubone frame.

![]()

Then your three bonus questions: was it made by MZ? Was it a V-twin? And what did MZV stand for?

Answers: no, no, and we don’t know.

![]()

While MZV was supplying export models for sale in the US under Safari branding, it was also producing models for its home market… Our MZV Cambridge is stamped with frame serial 10112-SS, which dates it to 1978, and lots of aspects of its late-70s’ styling would certainly still appeal today. It really has the look of a custom street-cruiser, which would probably now be popularly called a ‘Bobber’.

The Verlicchi frame looks street-tough, and the tele-forks with nice alloy yokes give the front-end a smart and sharp face with the small headlamp, and what rebel-rider even needs a speedo? The chrome-plated rear suspension units look as if they came from a much heavier motor cycle, and give the back of the bike a strong impression. Then the wheels, wow! No way do they look like they’re from a typical moped! A 2.75×16 tyre up front and 3.50×16 on the rear! They’re just so custom!

Look at the ‘Sanremo’ brand stamped on the rims, and that make has been ex-market for quite a while, so they do seem to be the originals. Maybe helped by the illusion of relatively small diameter 16-inch rims, the brake hubs look big too.

The wheels are barely covered by cool, street mudguards, which if they were underwear, would probably be called a G-string! They’re only just wide enough to cover the width of their tyres, and not long enough to serve any useful purpose at all if it rains. The front mudguard is so short (at both ends), that it ends at the same height as the top of the cylinder head! This is absolutely not a ‘working’ bike in any way, because if you ever rode it on a wet road, it’d throw everything all over the engine and you’d never get the corroded aluminium clean again, while the rear wheel would throw spray all over the bike and rider. California West Coast cruiser, but never intended for the real world.

The single seat is flat and still a very fashionable ‘Bobber’ style and there’s even more flashy bling in the form of a chrome-plated chain guard.

Though this MZV Cambridge is an original 1978 moped, it’d still be a very cool machine to ride in 2020—but it’s over 40 years old!

The silencer is some after-market pattern system that hasn’t been adapted to mount particularly well, but looks in keeping with the bike, and isn’t too dissimilar from the style of the originally fitted sort of system. The exhaust downpipe is 32mm diameter, which looks big and business-like too.

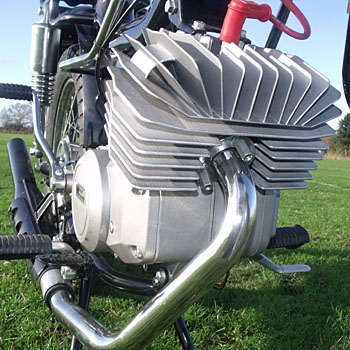

When you’ve just about finished being generally impressed with the look of the cycle chassis, there’s the Minarelli P4 engine with an enormous full-width finned aluminium cylinder and awesome radial-fin head, all sitting on an angular all-alloy case set. There’s no way you’d think it was a 50cc, surely that’s got to be 125cc plus? (No, it really is a 50.) The tubone frame particularly presents the engine as a visual feature and you can even look right down on it from the riding position! Having a great looking engine goes right along with the impression of the whole package.

Those chrome-plated street-cruiser handlebars have got the look too, and they’re the real McCoy, with neat welded-on lever brackets, and alloy levers.

This MZV Cambridge wears that whole street-cool image, and it’s sure got a lot of style and visual appeal. It’s going to look great everywhere you park it and every thieving scumbag is going to want to steal it, so you’d better get a big lock and chain!

The only obvious thing that might look a little less convincing to the knowing eye, is that it’s fitted with a Dell’orto SHA 14/12 carb, which is effectively only a standard moped-spec 12mm bore, and really isn’t going to allow that supersonic Minarelli engine to exploit very much of its potential—and because of the small carb, we’re going to bet it’s very likely to be under-geared.

The rear suspension top mountings locate on a tubular frame section, which doubles up as a rear carrier, and has a handle on the left hand side to help with lifting the bike off and back onto the stand. The handle is not really necessary though, because there’s plenty of other tubes in the frame section & rear carrier to take hold of, but maybe it makes a well-meaning token gesture.

We’re not too sure if the MZV might be classed as a 50cc motor cycle or a moped of the ‘new generation’ without pedals, but with a kick-start and footrests instead? It doesn’t wear any sloped 30mph restricted plate, but then it’s not a UK-market machine.

Starting is the usual kick-start moped procedure: just turn on the fuel, snap down the choke trigger on the carb, a couple of jabs on the kick-start and it fires straight up away with lots of revs and an angry buzz from the exhaust. Run a little to warm before opening the throttle wide to snap release the choke then a few revvy twists on the throttle just to satisfy ourselves it’s running clear and we’re ready to go.

The Minarelli engine has a 4-speed gearbox with left-hand rocking-pedal selection, forward/down for first, then heel-back for second, third, and fourth.

The clutch lever action feels very heavy for a 50, and so stiff that it’s actually difficult to feel the point at which the clutch starts to bite, while the gearbox shows a nice light change action with a positive click selection.

Our pacer peels in behind as we pull away, since the Cambridge has no speedometer, so we’re relying on our shadow again to take the readings.

First gear will only get you to about a screaming 5mph, so it’s like you’re having to change into second the moment you’ve just got moving. The motor is obviously capable of producing good power, but you’re not going to be able to use it effectively with the current low drive ratio.

The Domino fast-action throttle doesn’t helps control either, as it has little controllable feel, so it’s mostly just all or nothing, and proves hard to find much happy in-between.

We’re not overly impressed with the riding feel of the cruiser style handlebars, which proportionately seem too wide for a moped, and give an over-correcting impression that the bike is lightly swaying along—maybe you’d get used to it? The riding position doesn’t work particularly well either, since 16-inch wheels result in a fairly short wheel base, and the seating position seems too close to the handlebars, so you do feel rather crowded for space at the helm.

On flat it gives 36mph in an upright position, in crouch on flat 37, and downhill 39.

Basically it’s under-geared so it revs out, and it is under-carbed with its Dell’orto SHA 14/12, which is probably just as well considering the relatively low gearing, because that puts at least some ceiling on the revs—otherwise it’d probably rev itself to death much sooner.

The acceleration isn’t particularly useable in the lower gears because you’re having to change up so quickly. The power starts to become more useful pulling in third and fourth, but the motor runs out of carburetion as the revs start getting up, so the performance starts to drop away just about when it should really be coming in strongly, so you have to change up gear when it runs out of legs. When you get to fourth and the same thing happens, then you’d like a fifth gear—but there isn’t one.

It’s under-geared, so it revs a lot, but doesn’t produce enough effective power.

The suspension worked well enough on our test ride, though the stout rear shocks felt somewhat over-sprung, but were probably compensated for by the pneumatic effect of the fat rear tyre.

The single-leading front brake plate has a sporty looking air scoop, but the brakes seem pretty poor considering the apparent size of the brake drums (around 120mm); the foot pedal seems to require more pressure in proportion to surprisingly less effect. Normally with the leverage power you can apply to a footbrake, you’d expect it to be much better than it is. The front lever too requires harder hand pressure than the brake seems to deliver. The brakes are generally capable enough for the performance, but if it were geared-up and carb’d-up, you could be finding the brakes more lacking if you wanted to ride the bike to its best.

All electrical fittings (headlamp, tail light, horn and switchgear) are CEV, and everything works as it should, though we did notice the headlight switches, off–sidelight–headlight, but without any beam–dip. The Italian market seemed to have different specifications in the 1970s.

MZV Cambridge SS, all looks and show, but no real go…

![]()

In 1975 MZV dabbled with a couple of 125cc prototypes with Hiro engines, Verlicchi frames, and suspension by Marzocchi and Corte Cosso. There was a road-going model, and trail-style Cross Regolarita, but only 23 machines were produced for assessment and the project did not proceed any further.

Further MZV moped models were equipped with Minarelli four- and six-speed motors, and Morini-Franco with four- and five-speed transmissions.

MZV brochure literature in 1983 was giving the company address as Via Edoardo Ferravilla 10, 40127 Bologna (Italia), though the area now appears to be mainly just urban residential flats with a few small shops on the ground floor, but with no indication of any industry there—so have things changed there that much, or was this no more than just a mailing office?

Models listed in the brochure were the Cobra (in an off-road crosser style), Cobra Tipo Ferrari, Cobra 85 Special 400MT, Cobra Mac1-ORO (all tubone roadsters), and Cobra Snupy OZZ.

MBI Safari lasted much longer than most US moped brands, from its start-up in the mid ’60s as First American Bicizeta, up to around 1991, and MZV seemed to be supplying them with various models right throughout most of the period.

We have no more idea of MZV’s end, than we do about its beginning, but may it be that the two symbiotic companies ended together?

![]()