1873, and on a small island in the Danube River, by the town of Riedlingen, two young mechanics named Heinrich Stoll and Christian Schmidt set up a workshop with an old English-made lathe and a waterwheel to provide the power. They called their new business Mechanische Werkstätte zur Herstellung von Strickmaschinen, which translates as ‘Mechanical shop for manufacturing knitting machines’.

Their manufacture and repair of knitting and sewing machines was well supported by the local Hausfrauen (housewives), and the company prospered to such an extent that a move to a larger factory at Reutlingen became possible in 1874. By the late 1870s, the partners decided to go their separate ways, with Heinrich continuing the original sewing machine business and Christian moving on to Neckarsulm in 1880. At a former Plaster-of-Paris mill, he settled down to continue the knitting machines while developing his own new sewing machine. Schmidt was a technically astute entrepreneur, and knitting machines of his now called Neckarsulmer Strickmachinenfabrick AG were produced almost exclusively for the Austrian market. There followed a period of rapid business growth. Christian was also following the increasing interest in cycling that was developing in the 1880s, and entertained prospects of manufacturing his own bicycle, but never lived to see his dream come true, since he died in 1884.

Management of the company was then left to his brother-in-law, Gottlob Banzhaf, but in 1885, Austria increased its import taxes fivefold, which dramatically compromised sales, so the company was driven to look toward other products.

The continuing and increasing demand for bicycles continued developing during the later part of the decade, so it was Gottlob who progressed the business into cycle manufacture in 1886. Their first cycle product was a Hochrad (high-wheeler) or ‘penny-farthing’ model as we know them today, which was mostly assembled from English parts, and sold as the ‘Germania’.

A ‘safety-bicycle’ designed by the Neckarsulmers followed in 1888, which was sold as Pfiel (arrow). By 1889, records show the 60 employees produced 200 bicycles alongside the dwindling manufacture of knitting machines.

As cycle demand progressively increased, the last knitting machine left the line in 1892, and a new brand name was established as NSU im Hirschhorn (NSU in the deer horn); NSU was obviously taken from the title letters of the two local rivers: Neckar and Sulm, but ‘n the deer horn’? We have no idea, though the company logo of the time showed the NSU letters within a deer antler.

The Niederrad (Envious Bike) model made 1893–96 became very popular and proved a sales success. All parts were now produced within the factory and, from 1892, it carried a badge ‘Original NSU’ on the cycle head tube, and the company name was now registered as Neckarsulmer Fahrradwerke AG (Neckarsulmer Bicycle Works).

Old company records from 1900 indicated some 450 workers producing 5,281 bicycles, and going on to the next step to manufacture the first NSU motor cycle in 1901. This was fitted with a 1.5hp Zedel motor imported from Switzerland, and around 100 of them were produced.

In 1903, NSU presented its first ‘all in-house built’ motor cycle, using a 2hp motor designed by Christian Schmidt’s son Karl. This proved reliable, sold well, and production soared to 2,228. Sales expanded and so did the factory. The 2hp model was followed by a water-cooled 4hp NSU, then some V-twins of 3, 3½, 5, and 5½ horse power.

By 1905 NSU was selling a very popular 3hp motor cycle model, and presented its first car.

Within just a couple more years there were several automobile motor choices being offered, from 1,300cc to almost 4 litres. NSU was also quick to appreciate the value of racing its products for promotional purposes, and that doing so had a positive effect on both development and sales, so there were many victories and records set.

In 1909 a 1,000cc V-twin motor cycle was introduced, while taxicabs and small lorries also went into production.

When war came in 1914, NSU was obliged to supply both cars and motor cycles to the Imperial German Army during World War 1, but experienced difficulties in regaining the civilian sales of this side of the business after the Deutsches Heer was abolished on 6th March 1919, and provisionally replaced by the Reichswehr.

The Great War left a lasting and detrimental effect on NSU’s business, and it was not until 1922 that the factory really got back on its feet again when 3,000 people were employed. Models produced were basically the pre-war machines up until 1924, when a completely new ‘unit-construction’ line came off the drawing boards. The first model was a 2hp side-valve single that was available with either two or three speed gearbox and belt drive, followed by a 4hp twin, then an 8hp twin with all-chain drive.

Aimed toward the utility market, the Kriegspony was an inexpensive two-stroke, clutched, single-speed, economy lightweight weighing just 11½st (73kg), with a top speed of 38mph, and over 100mpg.

In 1927, NSU became the first German company to build cars on an assembly line but, as a negative effect of the national hyper-inflation problems at this time, the car division was sold to Fiat in 1928 under an agreement that Fiat would commit to continue to build NSU cars until 1932.

In 1929, Walter Moore, the English designer of the original overhead camshaft racing Norton joined NSU to re-establish its racing team.

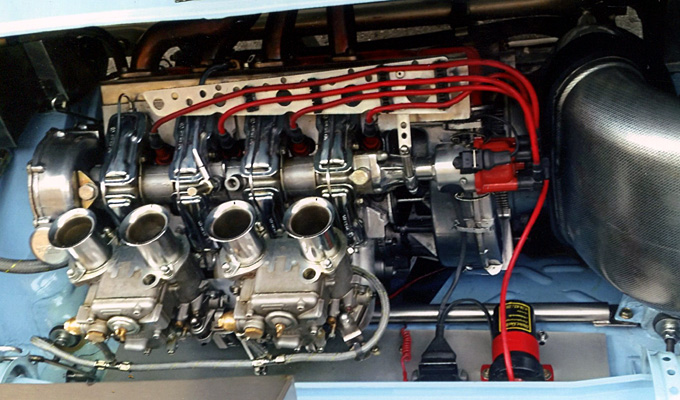

Fresh off the drawing board new 350, 500, 600, and 700cc single-cylinder ohc racing models were rapidly developed with a gear-driven overhead camshaft actuating two rockers and hairpin springs on the valves. Motors mounted an Amal racing carburettor at a slight down-draft angle, and was ignition by a Bosch magneto.

The engines were mounted in a single-loop cradle frame with a rigid rear and a girder fork at the front as the only method of suspension. A foot-change gearbox was fitted, and the wheels were built on cast aluminium brake hubs. The wrap-around oil tank was similar to that used on the British Nortons, and the long fuel tank was hand-beaten aluminium alloy.

The works racing team consisted of British rider, Tommy Bullus, and a German, Heiner Fleischmann. While the new NSU racers proved to be fast, they weren’t quite fast enough to challenge the top British marques, and the only significant success was by Bullus claiming an unexpected victory at the 1930 Grand Prix of Italy.

Into the 1930s, side effects of the Great Depression particularly affected the German economy, so NSU reacted by switching from expensive racing promotions, and instead producing cheap utility motor cycles. They even returned to a motorised bicycle in 1931. This was the 63cc Motosulm: a two-stroke cyclemotor engine mounted on the front fork and driving the front wheel through a clutch and chain.

In 1933, NSU assembled three ‘Type-32’ prototypes for Ferdinand Porsche, which became the predecessor of the Volkswagen Beetle.

NSU Quick

NSU Fox

1936 saw the takeover of bicycle production from Adam Opel, and two major sales successes in further newly introduced lightweight ‘Quick’ and ‘Pony’ models.

1939 brought World War 2, and yet again NSU had to produce for the military, designing and mainly building the HK101 Kettenkrad half-tracked motor cycle vehicle equipped with an Opel Olympia engine, and a 250ZDB army motor cycle.

NSU’s Neckarsulm plant was partly destroyed in a bomb raid just a couple of weeks before the end of the war, then used as an allied forces repair shop, until NSU managed to return the factory to re-manufacturing the pre-war 98cc Quick two-speed light motor cycle later in 1945. Pre-war 350cc Konsul-1 and 500cc Konsul-2 motor cycles were also returned to sale to match similar models by BMW and Zündapp in an effort to maintain market share.

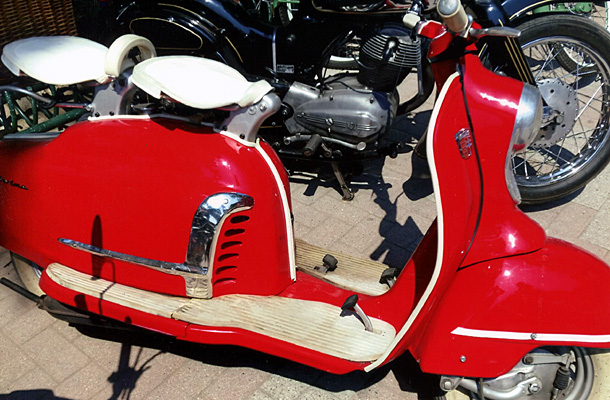

In 1948, NSU celebrated its 75th anniversary by presenting a new 100cc 4-stroke ‘Fox’ model, which was marketed with the slogan “Fixe Fahrer Fahren Fox” (smart riders ride the Fox). By the early 1950s, restoration of the plant and damaged equipment was recovered enough for NSU to further undertake manufacturing of the Italian Lambretta scooter under licence.

The older Konsul 1 & 2 models were withdrawn in early 1953 when the 250cc Max ohc motor cycle was introduced

Later in 1953 the NSU Quickly moped was introduced…

The Quickly N was the original and most basic version of the NSU Quickly, using the original version of the engine, 40mm bore × 39mm stroke, with a 5.5:1 compression ratio, output was variably rated as 1.3bhp @ 5,000rpm or 1.4bhp @ max 5,200rpm. The early Quickly version featured a left-hand mounted exhaust and a Bing type 1/9/1 carburettor with a flood button to the float chamber but no choke shutter, since it employed a strangler to the ‘wet element’ air filter mounted in the frame.

The N featured a manual two-speed transmission that was operated from the handlebar by a clutch, and it ran on 26×2 wheels front and rear.

Introduced to the UK from August 1955 the N was listed at £49–18–4d (+ purchase tax) in period advertising. Our example serialised 264422 was registered on 2nd September 1955, so it’s among one of the very first NSU Quicklys to come to the UK, and its last road tax ran out in December 1961, so 61 years in mothballs and it’s still in fantastic original condition.

Original specifications and period road tests quoted 180mpg economy, top speed around 40km/h (25mph), and weight as 33kg (more about the weight very soon, because weight parameters were particularly significant in Germany at this time, though not at all relevant in the UK).

German regulations of the time specified these early mopeds to be built within a maximum weight limit of 33kg, so the light construction would present some engineering challenges and limitations to various manufacturers’ designs. The NSU lightweight pressed-steel frame would probably help a little to keep the dry weight down, and the leg shield accessories would be excluded from the weight regulation. We’ve checked other period continental mopeds before, and some have seemed a little ‘over marginal’ on their weights, so has our standard NSU Quickly mysteriously piled on the pounds over the years? Rear weight 21kg & front weight 20kg = 41kg, so do we think the leg shield set, a dribble of gearbox oil, and about a litre of fuel in the tank will weigh 8kg? That’s 17½lbs. Really? Or is that another German bike to add to our list of machines that didn’t really meet the specified weight limit? The jury is still out…

While stood on its wire stand, the back wheel sits on the floor, and the front wheel is elevated with 3 inches of ground clearance—and that’s a lot! The bike looks precariously perched, though is actually quite stable—until some passing pedestrian might catch the front of the bike, wheel, mudguard, or handlebars, in which case the bike easily spins on the stand and might come to grief.

Probably the most obvious observation is that no one in their right frame of mind would consider trying to start one of these early model Quicklys on the flimsy wire stand, and neither should anyone ever think of sitting on the bike while it’s on the stand. The stand on our bike is actually in very good condition, so it’s seemingly never been abused, but we’ve seen a lot of teetering Quicklys with twisted stands over the years, and little prospect of ever being able to straighten them out again.

Push the bike off the stand, but it doesn’t return to the ‘up’ position with any spring assistance and just drags along the floor, because it’s just a loose and dangly wire stand which requires the rider to push it up with their foot until it locates in a spring clip on the frame to secure it. One might even call this primitive.

Petrol tap Z off–on–R res at the bottom right of the small 5⅓ pint ‘peanut’ tank (later tanks were increased to 1 gallon capacity).

The early Bing 1/9/1 carb only has a tickler button to the float chamber top (later carb types were changed to Bing 1/9/22 with shutter type strangler choke), and we usually found tickler flooding to be more effective than trying to start by the choke control on the left-hand side of the frame. This is a lever on a disc, marked with an anti-clockwise arrow pointing to ‘Auf’ in the down position … and if you’re thinking Auf might be choke off , think again, because Auf in German = On. So up must be choke off? Can you imagine British customers not being confused by that? We were, so we just left the switch in the up position, and used the flood button instead.

The ‘approved’ Quickly starting method is absolutely off the stand, and spin the engine over in neutral with a downstroke on either pedal, whichever is in up position at the time. If it doesn’t start, then change leg and ‘kick’ with the other foot. If the pedal isn’t quite in the optimum position to press down, then pull in the decompressor trigger and move the pedal to the required spot. Pushing the pedal down is strongly resisted by the high pedal ratio and the motor compression, and requires firm pressure on the pedal, so it can help to get it spinning easier with a starting tweak on the decompressor trigger, then release the trigger to start once the motor is turning.

After a couple of firm spins of the pedals, the motor gently strums into life, and a plume of smoke floats from the end of the silencer, then leave it to warm for a while.

There’s a small ‘window’ in the twist control body to indicate the gear position, but it’s unhelpfully impossible to read from the riding position, so completely useless to the rider.

Haul in the clutch lever (that’s a really heavy clutch, despite having a new cable), and firmly twist the shift forward & down for first, which is pretty hard since you have to hold the hand-change firmly down as you release the clutch lever to ensure the gear engages—and we’re away. The motor proves very docile, gently and easily running at low revs as we pootle down the drive. While waiting for our pacer (our Quickly has no speedo) to get his act together, we idle time away by easily performing tight low speed turns without any tendency to falter or stall, so really useful torque if you’re needing to trickle along in traffic.

Joined by our pacer we cruise steadily around the course to just get an impression of the bike, and some aspects become pretty obvious. Both brakes are absolutely terrible. Even though the hubs have been cleaned out, it’s a low mileage bike and the linings seem good, but the front brake is so poor that it barely even rides up on the leading-link suspension!

You can apply a lot more mechanical effort to a rear brake by leg action rather than by a hand lever, and back pedal brakes are usually so effective you can often lock up the rear wheel if you apply them hard—except for the Quickly. You can stand up with your full weight on the back pedal, and it still barely slows down! We even spoke to other Quickly riders, and it was generously agreed that theirs barely work either. The consensus was that the mechanics of 26-inch wheels very much work against the small hubs and skinny shoes, and it really needed a bigger and better brake.

The general ride is pretty good considering the rigid frame, because the leading-link front suspension, 26×2 tyres, and rubber-covered sprung saddle effectively cushion most surface feedback. The handling on corners is also good, but downshift of the gear-change, particularly into first continues to be a big bugbear. Up changes from first back to neutral or through to second work fine, but down changes work against the spring loading of the gearbox selector. It’s not so bad going from second to neutral, though you sometimes have to ‘feel’ around a bit to locate neutral, but selecting first always remains a pain.

Turning onto the main straight, now with a hot engine, and a signal wave to our pacer, we’re recorded at a max of 19 in first, then hold onto second down the straight for a best on flat pace building up to 30mph before deciding it’s time to start pulling on the lousy brakes in safe time to stop for the upcoming junction. Comfortable cruising speed is around 25mph (all pacer speedo readings confirmed by sat-nav).

Back at base, we try the light switch—yes! Front and rear, and the horn buzzes too! Just thumb the decompressor trigger to stop.

In period road tests, Cycling gave Quickly ‘N’ 33mph on 14 April 1958 (bare frame), and 30mph on 22 October 1958 (with leg-shield set). Interestingly, Cycling stated in its report that they felt the ‘aerodynamics’ of the leg-shield set dragged the top speed down, and we recorded exactly the same result on our machine with leg-shields.

Later models of Quickly changed the exhaust system from the left side to the right side because it was always a bit too close to lots of things on the left, despite which we’re told the early left-hand exhaust models are now the real collectors’ piece. The headlamp changed from a blank shell, to a shell with a socket to take a speedometer, and the original Bing 1/9/1 carburettor was replaced by Bing 1/9/22.

The NSU Quickly was becoming a successful machine, with a new S model introduced in 1955 (1 gallon fuel tank, valanced mudguards, proper centre stand and prop-stand), a ‘Lux’ L model in 1956, Cavalino in 1957, and lots more … later models from Cavalino onwards quoted their engines with a compression ratio raised to 6.8:1, fitted with a 3mm larger Bing 1/12/117 carburettor, and power rated 1.7bhp @ 5,000rpm or 2bhp @ max 5,500rpm.

539,793 Quickly N mopeds were manufactured from 1953 to 1962, and more than one million Quicklys of all models had sold by the time production ended in 1965.

During the 1950s NSU had again started looking toward the resurgent car market, beginning production of twin cylinder Prinz cars in 1957, with subsequent model versions up to Prinz-4 in 1963, a Bertone designed Sport Prinz in 1959, and 4-cylinder Prinz 1000 in 1964 followed by larger 1085cc and 1177cc 1200TT model.

Both the 4-cylinder TT and 2400TTS engines were also used in Münch Mammut (Mammoth) motor cycles.

As car manufacturing was increasing, production of motor cycles was decreasing, the last scooters being discontinued in 1964, and NSU’s last motor cycle in production, the Quick-50, concluded in 1965. Even NSU-branded bicycles were now licence built by Heinemann, so all NSU’s eggs were now firmly in the automotive basket.

Working in cooperation with Dr Felix Wankel to develop his rotary engine design, NSU built the first Wankel motor that was ready to be tested in a car by 1960, and in September 1963 the NSU single-rotor Wankel powered ‘Spider’ sports car was presented at the Frankfurt Fair. 2,375 were built between 1964–67, but presented many problems due to insufficient testing, and particularly the rotor apex seals becoming prone to wear when the engine was started and being over-revved—which it did very easily.

The Spider was replaced by the twin-rotor Ro80, and unveiled at Frankfurt in 1967. Being launched for sale when it still had problems gave the car a reputation for unreliability, and a necessarily generous warranty policy had irreparably undermined NSU’s financial situation.

Under pressure from a large German bank as one of its main stockholders, NSU was acquired by Volkswagen in 1969, and merged with Auto-Union to create the modern-day Audi company.

Though most of the reliability issues claimed to have been resolved by 1970, the damage had already been done. High fuel consumption of the rotary engine further worked against the car following the dramatic international oil crisis of 1973, and the Ro80 remained in steadily reducing production until being discontinued in 1977.

The Neckarsulm plant was switched over entirely to producing Audi A2, A6, and A8 models.

By 1984 the NSU name had completely vanished from use within the VW/Audi organisation. Now only the address of NSU-Strasse remains for Audi-Werke in Neckarsulm.

Registered at the corporate address of NSU-Strasse 1, 74172 Neckarsulm, Germany, NSU-Gmbh still technically continues to exist, though purely for the corporate purpose of ‘Preservation and commercial use of the NSU brand, in particular the licensing of the brand and the distribution of spare parts, accessories or model cars under the brand’.