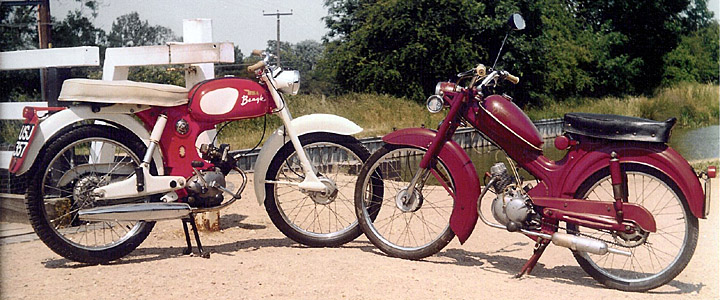

Once we’d thought of the concept of this epic double-test, everyone agreed that it would make the most incredible feature, and just had to be done. Two very different machines, linked by a common 4-stroke thread and a theme of their names, that missed each other in the market place by only a few short years.

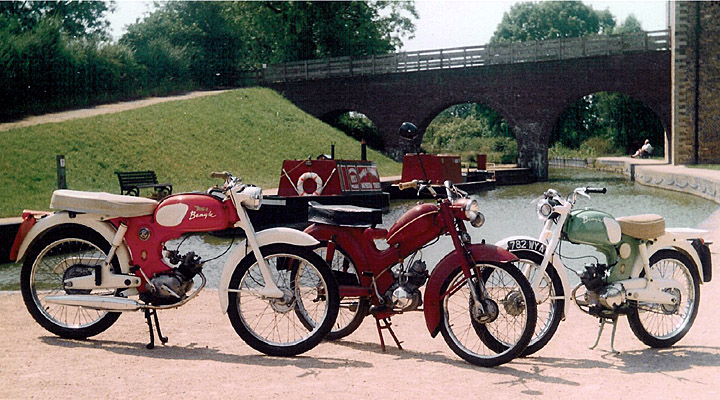

Two Dogs are: the cursed BSA Beagle, and legendary Dunkley Whippet!

While strictly pedal purists may be frowning at the presence of kick-start machinery in Buzzing, the stories of these two heroic failures certainly make for some fascinating history.

Starting with the oldest ‘tail’ first…

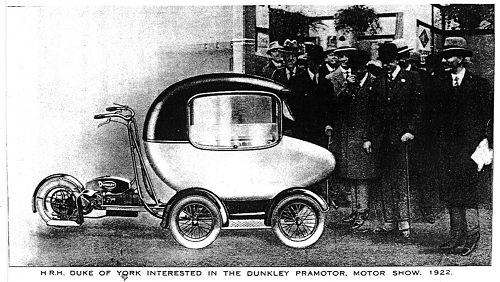

W H Dunkley established as a perambulator manufacturer at Jamaica Row, Birmingham from 1874. Versatility was the key to survival in Victorian times and a catalogue of 1880 illustrates their imagination: ‘Prams, rocking horses, see-saws, pedal tricycles, hobby-horse tricycles, mail carts, steam circuses & roundabouts with organ complete’! In 1886 they began production of a series of ‘gas cars’, which came equipped with a rubber tube for refilling off gas street lamps! Various models of motor cycles appeared around 1913, and a 3½hp Dunkley fitted with a 499cc Precision engine was entered into the 1914 Senior TT by G N Norris. It completed three laps before retiring. Despite diversions into other varied products, prams remained a constant in the core business. Appearing at the 1922 Motor Show, and powered by a 1hp Simplex engine, The Pramotor was a mind-boggling creation!

Even more staggering, listed in 1924, was a Pramotor 750cc V-twin with direct drive—it must have taken a mean nanny to bump start one of those!

Production of motor vehicles ended in 1925, from when the Dunkley name became synonymous with prams, leading to their position as the premier manufacturer. By the mid-1930s they had amalgamated with the Kensington Baby Carriage Co and acquired showrooms in the West End of London. Prams carried through up to their return to two-wheelers in April 1957, with the introduction of the Dunkley Whippet 60. This machine had first been shown the previous year at the Earls Court Show in November 1956, branded as the Mercury Whippet 60 and painted in Eggshell Light Blue. Though the machine never progressed beyond the show model under the Mercury badge, Dunkley sold a number of their early Whippets finished in the same colour, presumably using up the paint?

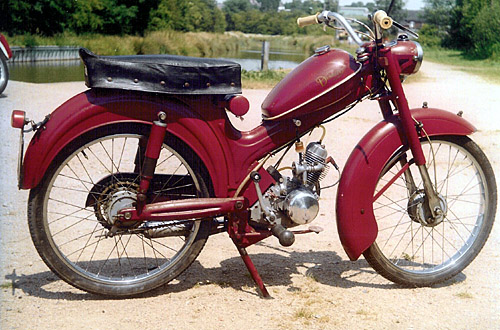

The Whippet’s main pressed steel frame elements are of Italian origin, but it’s difficult to be sure of the exact source since several manufacturers seem to have used them, Peripoli and Bianchi being mooted as favourites. Further chassis additions to adapt mounting of the engine and headstock bear all the hallmarks of Dunkley’s industrial grade handiwork. The front forks and petrol tank were common parts with Mercury’s Mercette (described in Buzzing, April 2002), a moped powered by a variant of the Dunkley engine, which appeared much earlier in 1955. Dunkley continued using these cycle components after Mercury’s collapse in March 1958, so presumably Dunkley were actually making them? Dunlop Endrick rims are laced onto B H Co full-width hubs, and we’re not fooled by the traditional Dunkley badge riveted to the back of the sprung mattress saddle, it’s plainly of Italian origin.

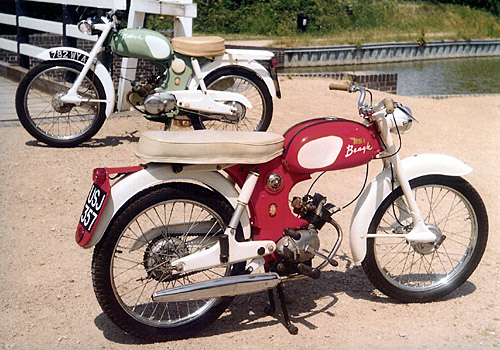

Now here’s where our rather unusual test machine has some slightly unconventional trim compared to the ‘official’ Whippet 60; you see, this feature bike is an ‘unlisted’ Whippet 65. Registered in July 1958, it features Dunkley Popular Scooter variant front forks with the handlebars clamped to the top yoke (the 60 has a stem mounted set) and a large Wipac headlamp to accommodate a Smiths SM3601 speedo (the 60 has a smaller headlamp with no speedo facility). Frame numeration follows a unique serialisation from the recognised 60 code—and it is installed with a genuine S prefix Dunkley Sports 65cc engine. Still painted in an original finish of what Dunkley seemingly described as ‘sparkling red’, which they listed for the Whippet 60 Commercial trade carrier. A number of deviations from the specifications suggest it is probably not one of these machines without its sidecar, and just when you’re starting to think it’s a freak—there are two such identical surviving examples recorded on the Dunkley register! One of these special Whippet 65 models was specifically selected for this feature so as to be closer for comparison to the 75cc Beagle in the test.

The S65 motor is 44mm bore × 42mm stroke to give an actual 64cc, with a 7:1 compression for 2.6bhp (the 60 used the same 44mm piston × 40mm stroke to give an actual 61cc at 6.5:1 compression for 2.4bhp), and yes, Dunkley really did offset the crankpin by that extra 1mm for the additional 3cc!

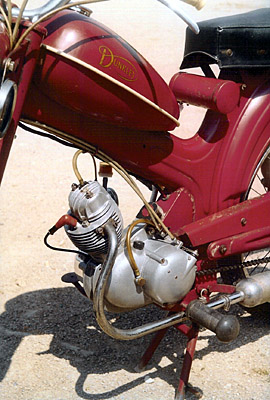

Designed by Bruno Fargion after moving on from Sinclair Goddard (Power Pak), the Dunkley engine has two-speed hand-shifted ratios, with the cam lobes located on the gear input shaft between first & second! The reduction primary drive gear train is indexed to maintain the valve timing, so the dry-plate clutch is mounted off the end of the output shaft between the gearbox and final drive sprocket—welcome to the world of crash change! The kick-starter ratchet mechanism spins the motor over back through first gear in the neutral position. A Wipac Series 90 flywheel magneto set hangs off the right hand side crank journal, so runs a wasted spark on the four-stroke cycle, while the engine is wholly reliant on splash/mist lubrication from little more than a small teacup of oil!

The push rod motor breathes as a crossflow, with the curly exhaust pipe sweeping away on the left, and an Amal 362 carb feeding down a curving aluminium manifold on the right.

The engine unit of the Dunkley Whippet

Ignition comes on at the first right position on the Wipac switch in the headlamp shell, choke up for starting by shutting a strangler on the carb intake, a couple of prods on the kick-start, and the Whippet roars into life. Wow, it sounds like it really means business! Clutch, twist into first with a clunk, wind on the throttle while feeding in the lever—and surge away up the road, roaring away with a fairly impressive sounding take-off on the NACC launch scale! Clutch, crash change into second, and once you’ve managed to struggle through the faltering carburation, the little four-stroke labours up towards a steady 30mph cruising speed.

The Dunkley’s fairly happy holding the urban limit, and there’s more in reserve when required, but handling is nervously light and follows a most uncertain course through corners. Though suspension is undamped at both front and rear, the Whippet rides quite firmly with just the rider aboard, but it is unclear whether it was very seriously meant as a dual-seater since the stubby saddle would probably be rather ‘intimate’ with a passenger, and it didn’t seem to come equipped with rear footrests. On the subject of the saddle, the mattress springing is very hard in the middle, and really does feel as bad as it looks! Second right position on the switch enables the generator lights, which prove dimly adequate, while a first left position is provided to operate the quaint dry-cell parking light system demanded by British law at the time. The rear brake, operated from a pedal off the right footrest, is very good and can lock up the wheel if not used judiciously, while the front brake proves no more than ‘average and adequate’. Despite the limitation of having only two gears, the Whippet digs in to hills, and without the need to change down, invariably manages to labour up quite challenging inclines in top.

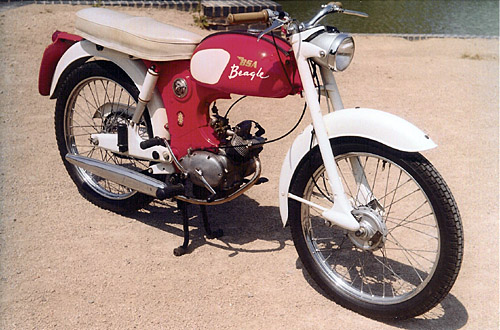

The 75cc BSA Beagle was announced late in 1962, though production was delayed and it was late ’63 before examples began finding their way to dealer’s showrooms. The intention was to respond to a growing number of sales being lost to imported Italian lightweight motor cycles, though the dealers were not so happy with the styling and leading-link fork arrangement, feeling the design was too conservative and dated. Drafted very much under the influence of Edward Turner, the same man who had innovated the Ariel Square Four in the early 1930s and introduced the Triumph Speed Twin later in the decade, it was felt to be failing to cut the mustard 30 years down the road!

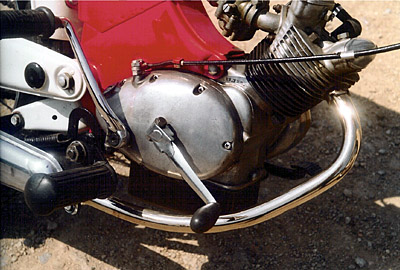

It has to be said, the Beagle engine has a dreadful reputation, but it wasn’t all rubbish; it did have some good features: gear primary drive and a smooth and precise four-speed gearbox. It looks very much like a miniature wet sump version of the Triumph Tiger Cub motor—and there’s the first problem: bump the tin sump pan and the fixing studs bend, resulting in that classic British motor cycling curse—oil leaks! Not so vulnerable as its 50cc version mounted in the low-slung Ariel Pixie frame, however, many Beagle engines were doomed to pack up for other reasons, before they got the chance to leak. The plain Vanderbilt bearing big-end was particularly prone to failure, but wasn’t really given much chance by the feeble single-piston oil pump, or the lack of sealing between the main journal and crankcases that allowed what little oil pressure there was to escape before it got anywhere near the crank bearing. ‘Lubrication of valve gear by oil mist’ proved generally not to be the case, with top-end wear and valve seizure being added to the compendium of problems.

When you wanted to replace the front sprocket, you would have to split the crankcases to access it! Now how stupid is that? Mind you, few Beagles were destined to last long enough to wear any of their sprockets out! Further ‘novel design’ mounted the fuel tap off the float chamber, leading to further inconveniences when you wanted to work on the carburettor.

The engine unit of the BSA Beagle

The Beagle’s not all bad—just mostly bad! All these are purely mechanical aspects, but when you look at these two nicely restored examples, you have to admit—they do look pretty smart! The D10 Bantam petrol tank suits well, and options of dual-seat and back-pegs, or single-saddle with rear carrier both looked nice and crisp, whatever the colour options.

Our red, dual-seat test Beagle has been mechanically improved by conversion to a roller bearing crank, and I have seen other examples further adapted with top-end lubrication by tapping off an external oil feed (obviously modifications for the very dedicated enthusiast).

Beagle’s ignition is isolated by a tiny toggle switch under the RHS of the seat (some pretence at security!) Whatever the weather, it usually requires flooding to start and the wretched float chamber vent always shoots a jet of petrol out over your gloves! A couple of easy jabs at the kick-starter and the motor starts-up like a muted sewing machine. Compared to the rumbling growl from the Whippet exhaust, the Beagle sounds a real puppy dog! The clutch proves rather heavier than expected for such a small machine, but the gears select nicely with a light and positive click. First proves very low, so you’re quickly changing into second, third, fourth—in fact, all the gears feel very low and it seems there’s a lot of busy whirring going on for relatively little progress!

As we break out into open country, Matthew Wileman on the green, single-saddle Beagle whizzes past in pursuit of Ian Marcer waffling away on the Whippet up ahead. Enough of being nice: the chase is on! Wind up the throttle through the gears, and surprise—the Beagle is transformed from a whimpering poodle into a rabid snarling terrier! Where it gives its best is being revved like a little sports Honda! The motor wants to be buzzed on the cam, and the two Beagles are tearing off and away together. Handling is very sure-footed, the suspension rides pretty well, both brakes are good, and even the lights are nice and bright. This really isn’t what you expect for a bike with such a bad reputation! The motor feels to be easily revving out in top, suggesting the gearing was conservatively pitched on the low side. The anti-clockwise speedo proves an irritation as you always find yourself doing a double-take to check which side of the 30 you’re on as we go through the speed cameras (not so much of a problem in the 1960s) on the way down to Moira Furnace Museum for the photo-shoot.

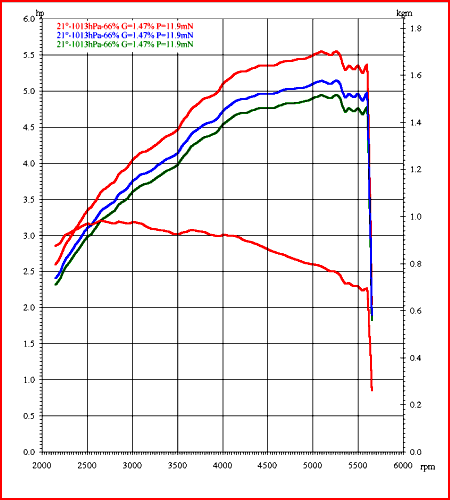

Dyno test result:

upper red line shows crankshaft power,

lower red line crankshaft torque

In the final dog fight of the on-road test, you have to bear in mind that we’re pitching the technological might of the world’s premier industrial motor cycle manufacturer of the day against the product of a pram company! From the moment the throttles are opened, the antiquated engineering of the Whippet is thoroughly outclassed by the superior specification of the Beagle. Acceleration, hill climbing, top speed, handling, everything; the comparison is startling—what a difference five5 years makes between these two little four-strokes. It starkly illustrates how obsolete the Dunkley was about to become. Dunkley claimed up to 45mph in period tests of their Sports 65, but now 47 years old, our best-paced speeds recorded the Whippet at 38mph on the flat (40+ likely downhill).

The Beagle’s performance advantages come from the flexibility of twice as many gears, an additional 11cc (18%), and higher 9.5:1 compression ratio, but scouring all available literature on the Beagle still fails to turn up any power rating. So, not to be denied, we drag the little hound down to Sid at Felixstowe Motorcycle & Auto Centre for a Dyno run. There is of course no programme file for a Beagle, so all the technical data has to be loaded in before we can even start. Finally the result that BSA so much seemed to want to keep secret: 5.5bhp @ 5,200rpm at the crank, 4.9bhp at the rear wheel. Back on the road for the top speed test: on the flat, light tailwind, rider crouched—a very creditable 49mph, and with the speedo accurately matching the pace bike reading. (We did manage to see 51mph on the rig computer, but there’s no wind resistance to take into account on a dyno run.)

The Dunkley Whippet Sports 65 was introduced on 3rd October 1957, and Dunkley’s pram manufacture declared as ‘reduced’ in November. The S65 scooter was announced on 30th January 1958, the Popular 49cc scooter followed in August, and the Popular Major 65cc scooter in December.

It’s been widely repeated in several publications that the 1950s’ Dunkley who made the scooters and light motor cycles was not the same earlier Dunkley company who built motor cycles and prams, but it most certainly was: it’s just that the trail may have become confused because Dunkley went bankrupt several times. Somehow they always bounced back, until spring of 1959 when it was announced that Dunkley Products Ltd had been taken over by M G Holdings Ltd, who advised the further acquisition of Dayton Cycles in May 1959, and that Dunkley production was being transferred to Dayton’s Park Royal site. It seemed little more than an asset stripping exercise and building out of stock, as the Dunkley range was dropped at the end of 1959, while Dunkley’s former site of National Works at Hounslow was shortly occupied by Scootamatic for local distribution of their listed imported motor cycles, scooters and Auto-Vap mopeds. Dayton products were also finished after the sales season of 1960, and by February 1961 it was announced that all remaining Dayton and Dunkley spares had been disposed of to Viscount Motors Ltd London W13.

BSA’s agents were very unhappy with the bitter experience of the Beagle engine; it developed such a troublesome reputation in the field that orders dried up and it was withdrawn in 1965. Forty years later, there are still quite a few Beagles around. We continue to be drawn to them because they are pretty little bikes, but their speedos always show low mileage, and the engines can still rarely be made to work for long. Seriously re-engineering the design failings is the only real solution, and Simon Bateman at Nametab Engineering (01527-522266) does roller bearing crank conversions at surprisingly competitive prices. Both converted examples in this feature show the potential is there, and the Beagle’s curse can be beaten.