Continuing our adventure from the last episode, Two Dogs, way back in August 2005 … once again the second hand of the clock begins ticking backward! Faster and faster, spinning back through the decades. We wing toward Britain’s industrial heartland for another remarkably rare autocycle, and—the Last Flight of the Eagle!

Our involvement with this marque may only relate to a very brief period when the company produced an autocycle, but it’s sure been a long flight for this old bird!

The Coventry Eagle Cycle Co was a privately owned family business founded by Edmund Mayo in 1890, firstly building bicycles, tricycles, and early powered tricycles toward the end of the 19th century. Its first motor cycle appeared in 1901, and was built alongside the pedal cycles from which it originated. This expanded into a varied range of motorised models that were largely built up from proprietary components, and listed up to 1916.

Production resumed after World War I, and developed into a comprehensive selection of models, from 147cc Villiers to the mighty V-twin JAP-engined ‘Flying Eight’. As the Great Depression progressively affected global business in the early 1930s, Coventry Eagle reacted year on year by steadily reducing its list, and moving towards utility economy models. Many manufacturers went to the wall over this period, but a reputation for quality stood the company in good stead through these difficult times.

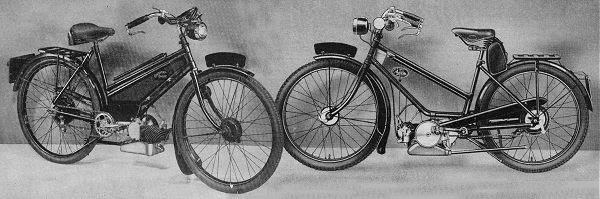

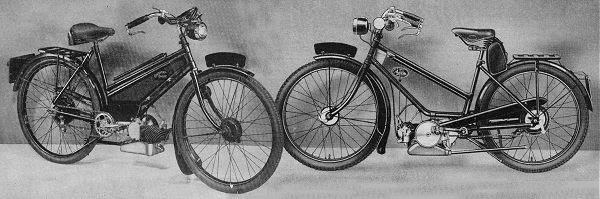

By 1936, the worst of the recession was past, and Coventry Eagle tentatively began to expand its range of machines again, though cautiously remained focused toward the economy market. 1938 found several manufacturers following Raynal and Excelsior in taking up G.H.Jones’s design licence for the Villiers-powered motorised cycle, and announcing their ‘Wilfreds″ (as the early autocycles were popularly termed by the press) before the Earls Court Show on the 10 November, in preparation for the 1939 season. Coventry Eagle joined the stampede at the eleventh hour, and a very hastily assembled ‘Auto-Ette’ prototype made a last minute surprise appearance on the stand, with a price posted at 17 guineas. All of the initial promotional material carried pictures of this prototype, but when the production Q12 ‘Auto-Ette’ (the Q prefix denoted 1939) arrived at the dealers, it notably featured a number of developments beyond the original show model, which was almost certainly cobbled together from stock trade-bike components. Changes for the production autocycle featured a lowered saddle tube and modified rear stay, the front mudguard now included lower valances, trim panels had disappeared between the bottom of the petrol tank and the upper engine mounting, and a number of other minor details were changed. Later, when the Auto-Ette sales leaflet came to be reprinted, the original prototype illustration was replaced with a new picture of the correct production machine—so there’s a challenge for any literature collectors!

Prototype (left) and production (right) versions of the Auto-ette

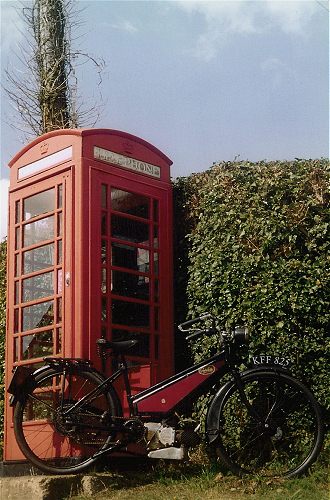

All pre-war autocycles are now past their official retirement date, seasoned old warriors that have survived a major conflict, but they just keep battling on! Falling right in with this description, our featured Coventry Eagle Q12 ‘Auto-Ette’ dating from 1939, carries frame number C3094, and is largely in original and un-restored condition. No superficial glitter here: it’s a weathered old charger that’s still out campaigning at events on the NACC rally circuit.

From the usual magazine ‘portrait’ pictures, you can’t really grasp the three-dimensional shape of that petrol tank, but it’s very ominously, well … coffin shaped! Appearing to still be trimmed with its original badging, it’s interesting to note some odd circular indents on the lower main sides of the tank panels, with small round indistinguishable decals set into the shallow pressed form—presumably to prevent the transfer being brushed when pedalling? Other attention to detail can be noted as the rear brake cable terminates in a short rod linkage to the pedal arm, and the convenience of forward thinking in the provision of a more practical centre stand in preference to the traditional rear stand fitted on most other makes. The impressive sprung pedal chain tensioner mechanism is worthy of comment too, being of such industrial calibre construction that it could honour a military vehicle!

The rest of the bike is fairly conventional period autocycle, with sturdy rigid forks and frame, pressed carrier and rear number plate. The overall impression is of sound engineering, durable construction and purely practical function, with little or no consideration given to styling. It’s truly: a machine!

Propulsion is supplied from the original Villiers Junior motor, cast one-piece cylinder and head, with deflector scavenging through a single transfer port for low rev torque characteristics, and that big brass flywheel just emphasises the fact!

The petrol tap is tucked down under the bottom right of the tank, though the choke control is made more accessible from the riding position by a linkage up the left side of the bike. Typically, flooding the carburettor proves unnecessary, and the motor chugs into life after a couple of spins. Junior engines invariably prove a little recalcitrant when cold so it’s usual practice to allow the motor to run warm a minute and clear the choke before embarking and, though it still spits and coughs when we go to pull away, a boost on the pedals manages to convince it that we are serious about going for a ride.

Slowing for the first junction finds a bit of groping down for the inverted brake levers and trigger-latch clutch, then back up top for the lever throttle again. All very muddled, and this is a control arrangement that’s going to take some acclimatisation. With brake drums the size of shoe polish tins, and performance relative to their size, sensible piloting of the Eagle requires adoption of a ‘forward thinking’ riding style. In terms of handling, the cycle chassis steers like a narrowboat, and though it seems to plough a straight furrow dead ahead, proves pretty unstable if you try taking both hands off the bars. Finding the time to signal much at junctions generally proves too much of a challenge, since you’re going to be too busy balancing all the controls.

Having previously ridden with this very machine on the 24th East Anglian Run, we already had first hand experience that this example was quite a goer, so, though we were expecting to record a good performance, it was still a surprise to get these remarkable results from the pace bike.

Typically of most early autocycles, a level of vibration readily comes in through the pedals but, on this one, doesn’t really seem to get any worse toward higher speeds. A comfortable cruising pace is found between 25 & 28mph, before more vibrations start creeping in through the saddle and make holding constant speeds above this figure uncomfortable and fatiguing. Once this Junior motor was nice and hot, we recorded up to 36mph on the flat with a light tailwind, and the motor pulling cleanly with barely any four-stroking. Downhill, 38mph, but because it was off-load under these conditions, four-stroke phasing was coming in intermittently. Pulling up a moderate incline, the revs fall back until the deflector transfer scavenging becomes efficient and the engine digs-in to maintain a steady 25mph hill climbing rate.

It’s normal for these old Villiers motors to choke and cough a bit when they’re cold, and you do need to get them hot before they start to run properly, but the Junior motor in this machine was a real stonker! Riding an antique autocycle like the Coventry Eagle at speeds like these is a real handful, and even if the bike might do it, the pilot isn’t going to want much of it!

The lights? Well, they glow in the dark. About what you’d expect from prehistoric electrics!

The R12 ‘Auto-Ette’ continued into 1940, and was joined by a R14 ‘Fly-Ette’ de luxe version with neat engine shields flared at the front as foot guards, and integral chain-guards on each side—but minds were very much focused on other issues by 3.30am on the 3rd June as the destroyer Shikari set sail: the last ship to leave Dunkirk harbour. In November of 1940, the Coventry skies darkened with the black crosses of the Luftwaffe, seemingly on a mission to eradicate the British motor cycle industry! The original Coventry Eagle factories in Bishopgate Green and Foleshill Road, along with the latest factory at Lincoln Street (taken over from Singer on 2 August 1937), were all bombed and burnt out.

After World War II, Coventry Eagle relocated to an ex-MoD factory in Duggins Lane, reverting to the manufacture of bicycles. In an interview of early 1947, Douglas Mayo suggested an intention to return to building motor cycles, but export orders for bicycles developed to such an extent that a subsequent statement of February 1948 reported there was ‘no capacity available for motor cycle production’, despite conceding to the press that they had carried out a ‘good deal of experimental work, and tested more than one interesting prototype’.

The site of the post-war plant at Tile Hill was required for redevelopment in 1959, so Coventry Eagle bought out Roberts Cycle Industries and moved to occupy their concern at Smethwick. Since Ernie Clements earlier became installed as Works Director, he introduced a new range of racing bikes known as Falcons, which over the years became increasingly popular. By 1968, the Birmingham site was up for redevelopment, and it was decided to relocate to the old Elswick buildings at Barton-on-Humber, that were no longer required by Hoppers. Falcon racing bikes progressively developed as the dominant brand after Ernie Clements had bought out the company, and moved the business inland from the Humber, to the old Corah factory at Brigg in 1973, now calling it Falcon Cycles. Cash flow pressures in 1978 resulted in Falcon being sold to Elswick–Hopper, later Casket, and finally to Tandem Group plc, as it still remains today: the UK’s largest cycle manufacturer. Reading down the listed Tandem brands are: Falcon Cycles, F Hopper & Co, Elswick Cycles, Wearwell Cycle Company, British Eagle, Townsend, Optima, Shogun, Claud Butler, and Coventry Eagle, which name is still occasionally used to badge models with more ‘basic features’.

Though autocycles were only made for the ’39 and ’40 seasons, they were built in quite significant numbers, achieving over 5,000 frame unit serials over this brief span and overtaking Raynal’s output in only half the time! Time however, has not been kind to these ancient autocycles: the register to date has only managed to record details of 19 surviving Eagles! Just as concerning, this 0.4% recorded survival rate is not untypical of other makes of antique autocycles!

The Q12 & R12 ‘Auto-Ette′ is very much among a rather select group of ‘particularly classic collectable autocycles’, and reflects in the above-average prices these machines seem to command on the rare occasions the odd example surfaces. The exotic R14 ‘Fly-Ette’ of 1940, with its engine side shields and integral chain-guards, should certainly be a desirable prize today—very few were made.

250cc JAP-engined Coventry Eagles were very successfully raced by Mita Vychodil and Martin Schneeweiss, and won many events. The fabulous JAP-powered ‘Flying Eight’ 1,000cc V-twin broke records at Brooklands, Coventry Eagle frames were used by Bert Le Vack when he raced the latest JAP engines in the early 20s, and world land and water speed record holder Malcolm Campbell (and friend of Percy Mayo) rode one as his personal motor cycle. Sadly, the Eagle has fallen a long way since its glory days of the 1920s!

Next: We are awakened in the early hours by a rustling noise in the corner of the room. Silhouetted against the night sky, a small demonic figure squats on the windowsill and beckons us to look through the glass. Illuminated in a pool of moonlight in the courtyard below, waits a strange moped … sent by The Devil himself?

This article appeared in the April 2007 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2007 M Daniels. Montage ©

2007 A Pattle]

Coventry Eagle involved quite a bit of research to unearth the relevant fine detail, and a very considerable communication and data collation exercise to get it all assembled. Some articles come together fairly naturally, but The Eagle was a real hard slog, with many re-writes to get the text to flow. Though the photo-shoot was a simple low budget set, the subtle jewel was the ‘period picture’ of the two old Eagles … an impossible montage, it never happened! So how was it done? It started with Paul Nelmes tracking down perfect examples of two original sales brochures illustrating the prototype and the production bikes, then a bit of wizardry with digital manipulation—and all so you could compare adjacent machine features in the same picture! And it worked so well, that nobody even spotted it wasn’t real!

Prototype (left) and production (right) versions of the Auto-ette

| CAMmag Home Page | List of articles |