We feed the new co-ordinates into the navigator to trace the history of our latest feature machine, and pull the travel lever. On this occasion however, the journey seems to take an unusual length of time, and we step out onto a bustling Victorian street!

We check our calendar, what? … It’s 1880!

Surely that can’t be right, since this year predates the modern bicycle as we have come to know it! But no, the flight recorder indicates we have reached our intended destination! We wander the streets, stepping aside for occasional horse drawn carts, curiously peering into shop windows, puzzling as to why our time machine has brought us here, then we round a corner and, standing by the side of the kerb: the answer may be revealed!

It’s a tricycle, but not just any tricycle, since this tricycle features an ingenious tilting device, and can actually be banked into corners! While we are scrutinising the mechanics, a smart young gent in a pinstripe jacket appears, and turns out to be the owner, who appreciates our technical interest. We chat for a while about his fascinating machine before the buzzer on our wrist pager reminds us that time is pressing to move on with the tale.

The time tumblers start turning once more, spinning forward through the 20th century, before slowing again, to land us inside the London Patents Office! It’s late in the evening, so the building is closed and all locked up, allowing us to wander at will through the maze of rooms and files. The only way to find out why the navigator has brought us here is by using our trackers, which lead us to two particular records. The first, being registered in 1958 by Homer Geiser, is for a three-wheeler cycle having two fixed upright rear wheels and a single-wheeled front tilting section. The second, registered in 1959, covers a similar development registered by Earle Hawke. Neither of the designs appeared to have progressed beyond the concept stage.

As daylight streams in through the office windows we hide ourselves away until the building is opened, then simply walk out unchallenged through the front door. Outside, we hop aboard a passing bus, following the navigator’s next directions to track down another gentleman, a little further forward in the future…

Our particular focus on this bizarre build up begins around 1966, from the basic idea to design a better and safer trade carrier type delivery bicycle.

To this purpose, George Leslie Wallace established a small design company called G.L.Wallis & Son, at Surbiton in Surrey, which consisted of just three people: George Wallis, Tony Wallis and Stan Jackson. The following months were spent brainstorming every possible variation in bicycle design, though without actually achieving any new ideas. George went on holiday to Spain and, while there, came up with visionary idea of the future, of a pivoting tricycle that would lean like a motor cycle on corners. On returning from Spain, the team conducted a patent search and found three early patents for articulated motor vehicles dated 1897, 1901 and 1905, applied for copies of these documents, studied them and built scale models of all the respective plans. After some months of pushing models around the workshop floor they came to the conclusion that the original patents did not work very well because they gave a negative steering geometry that made their respective tricycle chassis quite unstable on corners. So they went back to making a new fully adjustable model that could be set to any head angle, pivot angle and steering castor angle they wanted to test.

The first Wallis concept design patents for tilting tricycles were filed on 30th June 1966 then, following a further few months of experimentation with the model in different configurations, they arrived at a set up which seemed to work, so the project then moved on to building a full size leaning tricycle.

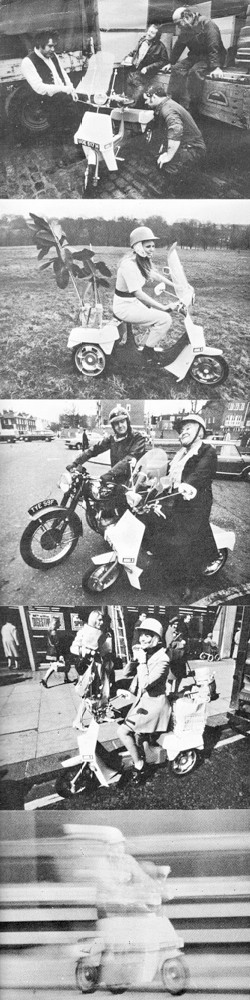

The model tricycle was completed and ridden for many miles to prove the system worked as hoped, then the next phase would be a leaning three-wheel motorised scooter using all the experience that had been gained from the tricycle. The scooter was built using a 75cc engine with CVT drive to a differential rear axle driving both rear wheels, and reportedly proved very stable to ride, cornered well, and proved almost impossible to fall off. It was ridden and tested around Surbiton almost continuously, and an article about it subsequently appeared in the local paper.

From this, the BBC put it on their science program (Tomorrow’s World?), as a new form of transport. During this time, world patents were taken out to protect the concept, and Wallis was contacted by BSA, who were looking for ‘something different’ to get into the moped market, and expressed an interest in this original concept.

An agreement was made with BSA giving them marketing rights, but Wallis retained control and the patents; so they would become consultants to BSA as the concepts became developed. The project was driven forward on the basis of ‘powerful market research’, which predicted a golden future and BSA reportedly tooled up to be able to produce 2,000 units a week. The planned moped-tricycle however, was independently ‘re-imagined’ by the BSA design committee, which failed to take much notice of advice or suggestions in its development of the concept.

So, when is a tricycle not a tricycle?

UK law defined the vehicle classification of a motor bicycle as ‘a two-wheeled motor cycle, whether or not having a side-car attached, and for the purposes of this definition where the distance measured between the centre of the area of contact with the road surface of any two wheels of a motor cycle is less than 18 inches (revised to 460 millimetres today), then those wheels shall be counted as one wheel’.

Since the proposed new tilting-tricycle had a centres distance between its two rear wheels of 15 inches, that meant it shouldn’t actually be defined as a tricycle. Also, having an engine of less than 50cc capacity, and being equipped with pedals by means of which it was capable of being propelled, meant the resultant machine would fall within the legal definition of a moped.

When the first prototypes were shipped to Wallis’s company for assessment, they were particularly unimpressed by errors in the geometry, which required rectification, and made many trips to Birmingham to correct some of the issues. During this development phase, Wallis’s team also built twelve leaning three-wheel ‘Trucksters’ for use as testing prototypes, which were based on the 98cc, two-stroke Triumph Tina scooter with CVT transmission, differential drive, and a 30-inch rear track width. Other prototypes were built with a more conventional layout of engine and larger wheel sizes.

US patents on the Wallis three-wheel tilting designs were granted on 7th April 1970.

In July 1970, and priced at £100, the world’s first production motorised tilting tricycle was announced to the bemused media, and whether it may be considered a novelty or gimmick, the originality of the concept was expected to generate much of its own free publicity…

‘Come in 007, close the door. Now we must send you on your most dangerous mission yet. Following the withdrawal of Raleigh from the market, Britain is suffering its greatest ever menace in the form of a two-pronged assault by imported mopeds from both Europe and the far-east. The BSA Design Committee however, has not been idle to this threat, so report to Q for your new secret weapon, and good luck—you’ll need it!’

Many readers will probably have long figured out where the build-up of this shaggy-dog story is leading and, of course, it’s no less than the infamous Ariel-3.

This is a surely a machine with a truly fearsome and unpredictable reputation.

In the early 1970s, I personally witnessed a lady actually fall off one while going around a corner. She ended up sitting in the road, while the Ariel-3 cruised merrily on without her, to gently come to rest and finally stopped, still standing upright, and ticking over in the gutter a little further up the road.

We’ve heard many stories from former owners of sudden punctures causing them to career out of control, and moments of inattention plunging riders into the verge before they have time to react. Others say that if you ride behind someone riding an Ariel-3, that you’ll never want to ride one yourself.

Back in 1970, just a glance at the Ariel-3 told you that you were going to need to re-appraise all you thought you knew about bikes … this was a very peculiar oddity! Where do you start?

The three pressed steel disc wheels are 2.00×12/16×2, which was the same size fitted to the Raleigh Wisp and the Clark Scamp, and originated from the Raleigh RSW-16 bicycle tyres sized 16×2.125.

The front fork (derived from the Triumph Tina) has only a single-sided leg with a compression and rebound rubber suspension arrangement on the single trailing link. This allows ready removal of the front wheel in motorcar fashion, by simply removing the three wheel nuts, and the front wheel is directly interchangeable with the rear wheels.

The main body is comprised of two large left-hand & right-hand steel pressings welded together, which contain the pedalling gear and chain, and two torsion bars to limit the angle of bank and stabilise the machine vertically when it’s parked. The left-hand brake lever has a latch to prevent the parked bike from rolling away and, with three wheels, no stand is required.

The propulsion ‘pod’ at the back houses the Dutch-built Anker–Laura engine unit in a sheet-steel housing with plastic sides, while further plastic mouldings are also used for the front mudguard, and gawky scooter-style front apron/leg shield set.

The seat column is an integral part of the frame pressing, and the seat pillar is adjustable for height between 26½ and 36 inches, and is topped with a German-made Denfeld rubber covered saddle.

The handlebars are adjustable for height between 38 and 40 inches, and carry Italian-made CEV electrics, with a headlamp in the crook of the handlebars and rear lamp fitted to the engine housing.

The Anker–Laura M 48-02 (UK spec) two-stroke under-square engine was given at 40mm bore × 38mm stroke for 49cc with 7:1 compression ratio and rated 1.7bhp at 5,500rpm. The motor is fed by reed-valve crankcase induction from a 12mm Encarwi carburettor (the manual incorrectly specifies a 14mm Encarwi, while other period reports also incorrectly quoted an 8mm Encarwi).

Because the engine is contained in a tin box that restricts airflow, a cooling fan is fitted outboard of the automatic centrifugal clutch, which means that the fan only spins while the engine is driving, but does not operate while the bike is stationary (which might be a consideration to keep in mind at times in standing traffic).

Sparks come from a Bosch mag-set with 6V, 23W AC generator output for the CEV lighting and electric horn.

The clutch delivers transmission via a toothed belt drive to a lay-shaft assembly driving the back nearside (left-hand) wheel only, and also the rear brake operates on that wheel only. The offside (right-hand) rear wheel just idles.

A six-pint fuel tank is mounted above and in front of the engine pod, with its filler in the middle below the seat.

Genuine accessories fitted to our example include the tinted screen, front carrier, and rear carrier, which also allows mounting of a spare wheel beneath (which can be useful occasionally, because Ariel-3’s are notoriously prone to picking up punctures).

To access the motor, you need to undo a couple of plastic locks at the bottom of the plastic sides and remove the filler cap, to tilt back the rear engine compartment cover, then secure with the small tie rod located at top right of the compartment by folding it up to engage in a hole under the cover.

Inside, you find there are two tool trays located on either side of the engine compartment, and air intakes below these to direct fresh air into the compartment while in motion.

There is a ‘free-engine’ mechanism, which allows you to disengage the motor for pedalling mode. This however, is an awful thing to access and operate, requiring lying on the floor to reach and withdraw a greasy sliding dog-gear against a spring, then rotating 90º to disengage—and it’s just as awkward to re-engage.

Starting: pull out the Ewarts fuel tap plunger under the bottom right-hand side of the tank, then turn to lock on. Twist the throttle forward to decompress, then pedal off and thumb the choke trigger beneath the left-hand bar. The engine turns over immediately since a sprag bearing in the clutch effects rotation, so you have to be prepared for some effort on the pedals, while the decompresser twitters out its vented gas in the bowels of the engine compartment behind. You need to build up a little speed to be able to maintain the momentum once you drop the decompresser and throttle back, or you may not be able to pedal it through compression.

Fortunately the engine fires up readily, then we tweak the choke trigger a few times if it threatens to peter out, until the motor runs clear. Opening the throttle gives rising revs, as the automatic clutch feeds in the drive. The Anker engine pulls off reasonably effectively on its own, though a little boost on the pedals can help initial acceleration. Throttle response from low revs is probably helped by the reed-valve induction improving torque, and the Ariel also gives a reasonable account against inclines.

General handling and cornering however are probably where things start to feel slightly less ‘confident’. On smoother road surfaces at lower speeds, all seems to go reasonably well. You can lean into the bends, point where you want to go, and the power unit behind just follows. As you enter bumpy bends at speed, however, the back wheels behind you can start bouncing off the ground because there’s not really any effective suspension at the back. The torque bars don’t actually manage to keep the wheels down at all times and, as the load changes on each side of the rear wheels, the left-hand driven wheel and right-hand idling wheel can start to make you appreciate the different and changing states of traction as you go round left-hand or right-hand bends.

There just seems something a little unpredictable about riding the bike at speed. The front wheel may appear to roll sideways in an understeer, while the rear wheels can feel as if they might be sliding away in an oversteer if you push it too hard, and these impressions seem to come in randomly and sooner through bumpy corners, so it’s probably life’s way of saying it’s time to slow down.

Turning bumpy bends feels quite jelly-like, almost as if you’re running low tyre pressures.

The Ariel-3 never came with a speedometer, and no capacity to even fit one, since none of the wheels seemed to have any facility to connect a speedometer drive, though you could probably fit a digital cyclometer today. We instead rely upon our pacer, who clocks our light uphill climb dropping slightly back to 24mph, which Ariel dealt with quite capably.

It held a steady 28mph along the flat, and topped out at 30mph downhill, which seemed fairly comparable to period test results.

We weren’t so sure about the adequacy of the brakes as the front felt a little spongy with more cable movement than we were comfortable with for relatively less effectiveness, while the rear brake felt firmer, but failed to live up to its promise. We felt the rear braking might have been better with brake hubs on both sides instead of just the left.

While Ariel-3 featured the equipment of a basic moped, its retail price of £110 (including 10% purchase tax … those were the days, 20% VAT now), was more expensive than many equivalent commuter mopeds.

Sales of the Ariel-3 dramatically short-fell the ambitious marketing predictions and, as early as mid-1971, BSA had already decided to close production, at which point manufacturing officially ceased.

While BSA had reportedly tooled up to be able to produce 2,000 units a week, the frame serial patterns probably indicate the true numbers produced: coding starts from 001nnn before progressing to 002nnn, up to 007nnn, which suggests that the whole production was probably less than a total of 7,000 units, and the misbegotten exercise was reckoned to have lost the BSA company some £2 million.

The ‘powerful market research’ that drove the project in the first place turned out to be a complete fantasy. The Ariel-3 was certainly an utter disaster, and undoubtedly shared some blame as the straw that broke the camel’s back, since BSA found itself trading with a £3m loss in 1971.

While shareholders were told in 1972 that, ‘errors of management had contributed to the financial situation’, the Ariel-3 was only one disastrous piece of the whole jigsaw, and ultimately, responsibility lay at the door of poor management.

The Ariel-3 was only listed for a short 3½-year period, and possibly all of the production may have actually been built in 1970, and then stocked until they finally cleared.

Despite the financial collapse of BSA in the summer of 1973, the Ariel-3 continued to be represented on trade listings until the December of 1974, when it was officially withdrawn, which was presumably when the last stocks had been finally cleared by receivers of the former business.

Wallis had earlier continued to work on developments of different versions of the tilting design with the twelve prototype trikes based on the Triumph Tina scooter, which employed the Tina’s automatic transmission driving the rear wheels via a differential. The Truckster prototypes reportedly disappeared into BSA, supposedly never to be heard of again, though certainly at least one example is known to survive. Due to appreciation of its obviously developing financial problems even as early as the late 1960s, the company had become reluctant to fund any further development of other variations of the design. Under these circumstances, George Wallis’s agreement with BSA allowed him to retain the rights to different tilting design variations, with the engine mounted onto the chassis instead of a rear pod, and using CVT with differential drive. A new Wallis prototype machine had already been built and K-registered in 1972 with its engine in the conventional moped position, bigger wheels than the Ariel, and full suspension, with telescopic forks at the front, and a torsion bar controlled de Dion rear axle. Although fitted with pedals (which was a legal necessity to qualify as a moped in the UK), the engine had a kick-start. The automatic CV transmission could variate between 24:1 and 11:1 ratios and, despite all these extra features, actually weighed-in less than the Ariel-3.

As a result, Wallis entered into negotiation with ‘a nameless foreign car manufacturer’, who was not disclosed at the time, but subsequently turned out to be Daihatsu.

In Japan, Daihatsu put the new tilting-trike design into production in 1974, making further developments such as moving the engine back into the rear wheel pod, reducing the wheel size again, dispensing with the pedals, and fitting leading-link front suspension instead of the telescopic forks. The 50cc Daihatsu Hallo was never sold in the UK, although at least two samples did come here, which were shipped to J.J.Lee Motorcycles in the hope that they might become UK agents for the machine. Proprietor, Jim Lee, considered the Hallo an excellent machine, but previous experience of the Ariel-3 convinced him that there probably wouldn’t be any demand for it. Daihatsu also produced an ES38V electric version of the trike, which carried two 12V × 75Ah batteries, to give it a 30km range at a speed of 30km/h.

At the failure of BSA Motor Cycles Ltd, rights of the original tilting tricycle also reverted back to its principle designer, and since Wallis had now recovered control these other patents, he subsequently contacted further Japanese parties, who appeared very interested in the concept. Over the next few months Honda, Kawasaki, and Yamaha came to visit, each bringing their own engineers to test-drive and discuss the design.

A trade agreement was subsequently reached with Honda and all designs and prototypes were shipped onto Japan where they suggested they would probably not have a market for the final product until 1983.