Having crossed the mighty Pacific Ocean, we are

finally washed ashore in distant oriental lands, so strange it

almost seems like another world—and we’re becoming

concerned there might be something nasty lurking in the

bushes!

Having crossed the mighty Pacific Ocean, we are

finally washed ashore in distant oriental lands, so strange it

almost seems like another world—and we’re becoming

concerned there might be something nasty lurking in the

bushes!  Maybe this isn’t where we thought it might

be? Perhaps this is the ‘Planet of the

Apes’.

Maybe this isn’t where we thought it might

be? Perhaps this is the ‘Planet of the

Apes’.

From the original

Honda Z100 ‘Monkey bike’ ride model at Tama Tech

Motopia Amusement Park in 1961, came the production CZ100 in

1963,

From the original

Honda Z100 ‘Monkey bike’ ride model at Tama Tech

Motopia Amusement Park in 1961, came the production CZ100 in

1963, developed and

equipped for use on public roads, and many derivations of

successive Z-series Gorilla and Monkey style mini-bikes have

continued in production ever since.

developed and

equipped for use on public roads, and many derivations of

successive Z-series Gorilla and Monkey style mini-bikes have

continued in production ever since.

Following along this popular theme, Honda introduced new ST-series 50 & 70 mini/monkey bike models in August 1969. More commonly known as ‘Dax’ models across Europe, these machines were particularly identified by a distinctive and new T-shape pressed-steel frame design and powered by the familiar C50 & C70 three-speed, semi-automatic engines. Their appearance, however, was completely unlike the established C-series scooterette range.

Dax came with swing-arm rear suspension and a small telescopic fork set, small but fat tyres 3.50–10, and a very compact 1 metre wheelbase. While it might seem unlikely to squeeze a passenger onto such a small machine, the frame is mounted with a dual seat and equipped to fit pillion footrests to the swing-arm—though space maybe somewhat limited!

The high-level exhaust system with perforated heat guard gives some impression of a light off-road machine, and its North American marketing under ‘Trail’ branding does slightly suggest this possible application.

The bike appears quite minimalist, due mainly to the apparent absence of any visible fuel tank, which is tucked away within the frame, and only holds a mere 2½ litres of petrol.

With a total length of 1.5 metres, width 58cm, handlebar height of 96cm, and given dry weight of 64kg (50)/65kg (70), the Dax would obviously be considered as a transportable compact. Some folding capability is enabled by separate handlebar arms, which can readily be unscrewed by hand-wheels for reducing the height down to 80cm for loading into the boot of a car, however it has to be considered this would involve lifting an ungainly all-up weight of 10 stone into place, which may not prove an easy single-handed task.

The four-stroke OHC engines are rated at 4.5bhp @ 6,000rpm for the 49cc & 6.0bhp @ 9,000rpm for the 72cc.

In UK listings, the ST50 Dax was imported from February 1970, but discontinued Oct 1971, to be completely replaced by ST70 from February 1972—so there weren’t many original ST50 Daxes sold in Britain, it was mostly 70s!

Honda did briefly produce a larger ST90 Trailsport model in 1972, primarily for the American market, but this was discontinued in 1974, so genuine examples are quite infrequent.

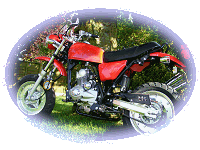

Our Honda ST70 dates from 1975 and remains finished in pretty much original pattern trim.

The design was very ‘of the moment’ for the new ’70s decade when it was first produced, and still endures as a popular retro-style fashionable icon over 40 years later, so all credit to this success of Honda’s creation.

The Dax impression is small, but chunky. The wide tyres convey a ‘solid’ look to its presence, and there’s also a slightly wedge-shaped form from the width of the saddle, the way the frame seems to ‘stand up’ on its rear shocks, and how the up-swept exhaust splays out to the back. Up front, the separate handlebar arms convey a very narrow look, with the slim headstock and low headlamp, so the forward view from the saddle is quite spindly.

With the speedometer mounted in the headlamp and a minimum of clutter to the handlebar sets, Dax does appear particularly tidy. The ignition key switch is just a simple off–on towards the left side of the headstock, while the light switch off–side–head is fixed through the left headlamp bracket. Just a front brake lever ahead of the twist-grip throttle, and horn button on the bar for your right thumb, which is almost busy compared to the left bar, having only a beam–dip-switch control on this side as the automatic clutch and pedal back brake to your right foot means the left cluster requires no hand lever at all, so the control features appear particularly simple.

The Spartan arrangement is very clearly absent of any indicator switchgear, which may be some surprise that winkers were never original equipment on these machines—but they really weren’t!

You access the fuel filler cap below the seat by releasing a latch from underneath the back. The fuel tap off–reserve–on is located on the carburettor, along with a lever operated choke, move up for on.

Going to kick the motor over, the auto-clutch frequently seems to irritatingly slip against compression (a common complaint with these motors), so you often need to ease the starter down until you can kick after compression to get the motor to spin and start.

The exhaust note is subdued and civilised, exactly as Mr Honda would like it to be and, after running the motor a minute to clear the choke, we’re ready to go.

Looking forward, the 50mph Nippon Seiki is graduated in bands, 13mph in first, 30 in second, and 47 in third, so this is probably an indication of what we should be expecting in performance.

There’s a traditional period rocking pedal gear-change at your left foot, back for first with typical crunch and a little lurch for good measure, and the green neutral light goes out. Apparently, it’s possible to get them to change into first smoothly and without this effect, but everything has to be set perfectly, the tick-over dead low, and the change clicked just right ... now back to the real world.

Simply open the throttle and the auto clutch feeds in as the revs increase. If you snatch open the throttle, then the clutch snatches too, so the trick for a smooth take-off is to ease in the throttle, then open up once the clutch has bitten. Alternatively, you can do like the kids do: rev the motor first, then kick into gear for a wild-wheelie take-off, which will always impress the punters ... if you don’t break the gearbox!

We don’t approve of any of that nonsense, so endeavour to do things properly and set a good example.

Two positive clicks forward are required for second since the box doesn’t go though neutral, then another click forward for third.

The essence for a smoother take-off is to start in second, which is actually the recommended method by the manufacturer—first was really only intended to get the bike moving when carrying a pillion passenger, or for hill-starts.

The 70 motor pulls consistently and cleanly right up its range, you can putter peacefully along at whatever contented pace you chose, which may be well within the urban limit, since if you’re unaccustomed to these machines, the revvy motor can begin to sound pretty busy at 30mph. The performance doesn’t stop there however, since the engine runs upward to seemingly howling revs—because that’s just what Hondas can do!

We run the first couple of miles at a reserved pace to build some heat into the motor and develop some feel for the bike, particularly since our handling experience with a number of small wheel machines over the years has made us slightly cautious about the nervous temperament of some examples.

No concerns with the Dax however as Mr Honda seems to have sorted that very well with the wide tyres and effective suspension systems—these little bikes ride and handle very confidently! Happy with Dax’s characteristics and riding manners, we step up the pace by cranking on the throttle, to which the exhaust responds with a muffled roar. Crouching down along the flat we run a best of 42mph into a crosswind. Tucked in for the downhill run we only have opportunity to snatch a brief glimpse of our speedo needle passing the 45 marker, so it’s a good job our pacer is at hand to report our best dive at 47–48mph.

Dax charged the uphill section and maintained a strong climb, cresting the rise at 32mph, a creditable showing and reasonable enough not to irritate impatient car drivers that sometimes track our steps through this section.

With the motor now thoroughly hot, turning into a tailwind and tucking down, Dax could now be easily worked up to 45+ on the flat, and that seemingly innocuous little 70cc commuter engine certainly howls at speed.

ST50-M Dax 4-speed manual clutched versions were also produced from 1979.

Original Honda Dax models were introduced with CT serial prefixes up to 1981, after which the design became licensed to Jincheng in China, who continued production of Dax models with JH2D serial prefixes into the late 1990s.

Honda’s registered patents for the ST-series Dax design expired in 1998, and have subsequently been further ‘replica copied’ by several Chinese manufacturers and continued to appeared under Jincheng branding, Lifan, Panda, Redcat, and other labels.

Further to the Dax ‘monkey bike’, Honda also produced another mini-bike derivative, and introduced the CF70 ‘Chaly’ in June 1973. The CF-series Chaly models are characterized by a U-shape, ‘step-through’, pressed-steel frame, which distinguishes these machines more as utility/shopper ‘Monkey’ derivatives, rather than the fun/recreational appeal of the Dax range.

Dating from 1976, our featured Chaly though, seems no longer quite what Mr Honda intended ... it’s been ‘restored’. Some years ago one may have said it had been ‘customised’, but that term has become somewhat eclipsed in the recent age, where it might now be described as ‘bling’, to which a few unkind people have adopted re-title of this bike as a Honda ‘Chavy’!

So, as they might say today, it certainly looks very ‘blinged’ to us!

Much of the original subtly has been ‘rinsed out’ in this ‘Walton Works’ re-invention to a bit of a ‘girlie hairdresser’s bike’, which concentrates a lot of focus to superficial appearance in a Harley–Davidson ‘Candy Brandy Wine’ translucent colour over a silver reflective base, with a metal flake and lacquer finish (this is a summarised account of a very detailed process description, presented in more gory detail in the ‘Directors Cut’ production notes).

Princess Barbie might seem right at home riding this bike to the glittery disco, getting hyped-up on orange juice, and dancing the night away round her ‘My Little Pony’ handbag, but don’t be fooled by the camp looks, or you’re going to get a real shock—this little bike is ferociously equipped with some serious 21st century girl power!

Most of the tricks are subtly camouflaged behind the plastic legshield set, but there are a few clues to give the game away. That big-bore JMCA stainless-steel sports exhaust for a start and, looking at it, you’ll probably also notice the special alloy box-section swing-arm, a popular conversion to improve handling ... and we don’t recall the carburettor top normally emerging through the legshield ridge? Ahh, yes, that’s because this is a much bigger carb, so the plastics have been neatly cut away to clear the larger body and choke control.

The left handlebar on a Chaly is normally bare, since the standard 70 has 3-speed semi-automatic engine, but our bike has a lever, so there’s a manual clutch now ... and isn’t that a pretty mighty looking kick-start for a little 70?

The aluminium engine casings all look representative of what you’d expect on the original Honda motor, but peep under the legshield set (if you dare), and there’s a 140cc XY series-3 pit-bike engine lurking inside!

This Chaly monkey shopper reveals a terrible secret about hairdresser Barbie—she’s actually a psychotic, power crazed, speed demon!

The wheels are standard size 3.50–10, but fitted with modern Continental scooter pattern tyres, the back one being noticeably ragged at the driving edge of the tread, where furious power delivery has started to rip it away against the road surface.

There are several indications that this tiny bike is likely to deliver a lot of performance, so this is probably getting about the time to start treating this machine with a little more respect.

An ignition switch is located off the left side of the top yoke, and we observe all the original steel fork shrouds have been replaced with rubber gaiters and trendy chrome headlamp brackets. Chaly’s petrol tank is accessed beneath the saddle and there’s a fuel switch mounted through the left hand frame below the seat. It’s a little fiddly to pull on the choke knob through the vents in the legshield set, though the standard equipment would probably have been a little more accessible.

You don’t want to be jabbing at the kick-start lever on these motors in the same casual way one might with the standard 70 engine, there’s a lot more capacity and compression to deal with on these new generation motors, so load up the starter and kick through compression to avoid straining the ratchet mechanism (which can be prone to fail).

Just a tweak of throttle and our motor growls into life with a deeply muffled thumping tone that sounds nothing like the gentle and inoffensive note of Honda’s original engine. Nobody is going to be fooled once the engine is started on this Chaly—it sounds a bit of beast!

A few more blips on the throttle and we can clear the choke by pushing in the button; clutch, then four gears all down with neutral at top. Power from this motor makes pulling off easy from low revs as you slip out the clutch, but opening the very responsive throttle produces an instant and snappy reaction, so it’s not so easy to manage a smooth take-off in the lower gears.

Winding back the throttle in first or second is likely to find this eager machine aviating the front wheel, and it really helps to lean forward if you’re going to give it the gun—but do appreciate this is exactly the riding style that is eating the rear tyre!

Power delivery proves more manageable by third gear, when you can more controllably open the throttle full without so much danger of losing it down the road from the brutal acceleration. You wouldn’t normally notice this engine performance so much in the more usual pit-bike applications, since their knobbly off-road tyres slip on the dirt and soften the power delivery, but in the lightweight Chaly chassis on high traction road tyres, it’s pretty savage—and fast, if you can handle it!

The power delivery goes right up through the gears, into top, where it still pulls like a train on the throttle. Our usual downhill–uphill trials would be absolutely no challenge for the power in this bike, so we just settled for an out-&-out ‘on-flat’ performance test.

Running our outward leg into a strong headwind to get the motor warm and a feel for the handling, we turned into the tailwind for a full-bore blast down the straight in full crouch. Having an engine twice the capacity of the original dramatically powers the bike up its range; the original 50mph Honda speedo is rendered useless as our Chaly runs it straight off the end of the dial with another gear to spare! Changing up to fourth and powering on, the needle turns off the end of the graduated scale, past the mph marker, into the uncharted zone beyond, and finishes pinned up against the end stop at far right of the clock. Snatch a quick glance back to see our pace vehicle is chasing hard to keep up, so tuck right down into full crouch, throttle full on, exhaust note a loud roar, engine running smooth as the revs continue building down the straight—70mph!

Hustling the Chaly through a bendy section was enough to lose our hard pressed pacer, who could no longer keep up, which established the handling was also up to the performance, though maybe another 5 poundss pressure in the tyres could have improved a slight tendency to wallow on bumpy curves—but we were pushing it hard at this point, so maybe the comment isn’t really warranted.

Remarkably, Honda’s standard drum brakes still proved effective and adequate against the engine up-rate, which was a most unexpected surprise.

For such a small bike, we were irritated how Chaly proved particularly cumbersome to navigate around the workshop due to its limiting steering stops, so we thought to check its full lock turning circle out in the road: 12ft! Unbelievable? Ridiculous, but true!

The bling ‘in your face’ paintwork and white saddle might not be to everyone’s taste, but sheer blasting power and performance of this little shopper monkey certainly earns our respect.

CF50 50cc Chaly models were also produced for some markets.

A Chaly CF70K2 variant was introduced in 1978.

Honda Chaly and Dax monkey bike imports to the UK were de-listed in Feb 1980, though continued a little beyond this time in other markets.

Patents for the Honda CF Chaly series designs also expired around a similar time as the ST Dax in 1998, and CF Chaly replica models and derivatives still continue to be produced by a number of Chinese manufacturers.

Following our Dax and Chaly pressed-steel frame variations upon a theme, we finally get back to where the ‘Monkey’ phenomenon actually started, and what is more commonly known today as ‘Gorilla’.

The modern Gorilla is really a direct descendent from the original Z-series Tama Tech and, characterised by its tubular steel frame design, actually remains the closest subsequent monkey to the founder of the genus. Gorilla is still the smallest of the monkey bikes, but has grown up a little over recent years as some modern derivatives seem to have evolved appreciably more powerful engines.

Sky Team Corporation Ltd was established in 1999 to produce and distribute licence-built derivatives of Honda Z-series bikes, made by the Jiangsu Sacin Motorcycle Co Ltd in China. The range has subsequently expanded to include a range of larger capacity on-road, off-road, and sports machines.

Our example of a Sky Team Gorilla dates from 2007, only six years old, but has already been extensively customised, and seemingly very little of the original machine remains—such is the rate of ongoing evolution.

Some surviving vestigial indicator that it might have initially been fitted with a 50cc motor, is a tiny 45mph round speedo mounted in the headlamp shell, but this token instrument doesn’t look as if it’ll be of much practical value today, since the chassis is now mounted with a Lifan 140cc, 4-speed engine.

The wheelbase of Gorilla is only 40 inches, or nose to tail just 56 inches, and with a saddle height of a mere 27 inches, this will appear quite a small bike to most adults, and is probably going to prove very cramped for anyone over 6-foot to ride. We incidentally had a tall rider try it for size, and with a total clash of knees and elbows, this really didn’t appear a suitable mount.

There’s a generous sprinkling of ‘custom goodies’ all over our machine, which seems a very popular fashion with monkey bikes these days. Some examples we see out on the rally circuit seem to have been changed with so many custom components, including special aluminium frames, we occasionally wonder if the owners still have the original bike in bits at home!

You probably have to be something of a cult expert to be able to pick out all the after-market parts, and we’re not so up with all these latest accessories, but a few obvious components are the OORacing alloy rear swing-arm, addition of an alloy oil cooler, and stainless steel Scorpion exhaust system. We’re guessing the fork set has been changed, and the rear suspension, and the custom alloy disc-wheels now mount 110/80–10 tyres, which are over 4 inches wide (110mm), but only have a total diameter of 16 inches.

Starting our Gorilla is conventional modern practice. Fuel tap at bottom left of the tank on–off–reserve, click the choke lever at the carb, ignition on, and the motor fires within a couple of kicks to a loud muffled thudding tone from the exhaust. Attempting to switch off the choke prematurely will only result in the motor dying out, so you have to be a little patient and wait for the bike to tell you it’s time as the revs fall back ... then you find the crummy latch on the choke won’t release!

How hard can it be for the Chinese carb makers just to get such a simple thing to work right?

Once we’ve finally released the choke with a measured amount of force and abuse, a few blips on the throttle show the motor to be most eager and responsive. It seems immediately obvious this is likely to be another hairy ride.

Clutch lever action is light, with neutral at the top of the box and four-down selection giving a stiff and notchy change pretty much right through the box, which is not untypical of many of these Chinese gearboxes—it just seems to be something else they haven’t wholly managed to get right yet. Gearboxes and kick-start mechanisms reportedly often fail on a lot of these motor types.

Clutch engagement is sharp and snatchy, so it’s better to err on the side of caution with this until you get the feel of its bite. First gear proves very low ratio and great for snapping throttle wheelies, but not particularly practical for general road use—probably a higher drive ratio might be more appropriate.

Everyone is going to be very aware of the exhaust note when you open the throttle—it’s definitely LOUD! The tone is probably more what you might expect from a Goldie or Velo, but most certainly not from a miniature monkey bike! As revs rise the noise progresses through a deafening drone to an aggressive roaring crackle, and there’s nothing subtle about the decibel level being produced by the time the speedo needle is going past the 40 marker.

Trouble is, the noise will follow you everywhere you ride the bike, so there’s no getting away from it until you change the system!

Modern 12-Volt battery assisted electrical systems are generally appreciably more effective than the old 6-Volt AC flywheel magneto systems we usually test, and yes, Gorilla’s lights seem really good compared to what we’re used to—and we don’t often come across LED lights on our usual old-timers either. Gorilla’s Cat-Eye rear light set is all LED for the back light and indicators. These are characterised by clear white lenses with coloured diode emitters ... so where’s the reflector? Hmmm!

A combination of small wheels and powerful engine has the potential to result in some pretty hairy handling if it’s not done properly, but our Gorilla proves remarkably good in the handling department! It doesn’t take long to establish confidence in the road-holding, and you may very quickly find yourself hustling the little bike through green lane bumpy and twisty sections with full-on power.

Intrigued how this micro-bike manages to handle so well despite the monstrous power engine relative to its size, we stick it on the scales when we get back: 5½ stone front / 5½ stone rear—it’s perfectly balanced! Obviously the result is equally dependent on effective suspension and damping, but our Gorilla’s custom package certainly handled impressively well.

The rear hub brake operated by right-hand foot pedal proved quite effective (which you’d probably expect, since the physics of braking favour the small wheeled machine), the front disc however was dramatically over-braked and particularly required a light and controlled application or you might be finding yourself in a heap in front of the bike!

Because of the gearing Gorilla is running, the engine will easily rev out in top gear, at which the motor is quite harsh and angry, while the exhaust will be emitting a deafening racket. While seemingly being constructed for total blasting performance around town, this tiring 140cc engine is seriously under-geared in the Gorilla frame, and revving itself toward a premature retirement.

Best on flat was tracked by our pace vehicle at 50mph. It proved better to lean into forward crouch while accelerating hard, to help keep front wheel on the ground, because although the coarse motor was certainly getting weary, it was still quite capable of rearing under throttle if the rider was sitting back.

Since this is such a small bike, running at speed can feel a lot faster than it really is, and you could easily be further misled by the inaccurate and optimistic ‘toybox’ speedo which proves exactly as expected, indications prove fairly vague and the needle readily runs off the end of the dial into no-man’s land.

There would have been no point in our usual downhill–uphill trials since Gorilla was quite capable of topping out on the flat, and produced more than enough power to make the uphill climb a practical irrelevance.

Various ‘Gorilla’ type monkey bike derivatives remain in production with a number of far eastern manufacturers,

Over fifty years on from the original Z-series design, the formula is still a success.

Registered in 2008, our fourth feature machine might be considered as ‘fringing’ the traditional ‘Monkey Bike’ category. Apparently based upon a motor cycle design, but shorter due to its small wheel arrangement, this bike is just a little larger than traditional ‘Monkey Bikes’ and a style now seemingly classified as ‘Ape’—which is exactly what the manufacturer calls it.

Readers will probably feel none the wiser for reading the bike is of Chinese origin, made by Huzhou Daixi Zhenhua Technology Trade Co Ltd, but it seems the company does a certain amount of manufacture for the Jincheng brand, and may go to explain the JH2D prefix on later Dax production (Jincheng Huzhou 2 Dax?).

Registered as a Zhenhua, our ‘Ape’ has a 50cc OHC motor with four-speed foot change, manual clutch, and wears a limitation plate indicating its restriction to 30mph—so qualified within the legal definition of a moped.

Kick-start or electric starting are options for getting the engine going and, since we rarely have the privilege of such luxuries on most of the old machinery we test, we choose to enjoy the novelty of exercising our thumb for a change: zig, zig, zig, brmmmm! Well that was much easier than pedalling the living daylights out of some reluctant old autocycle!

Reportedly proving pretty dismal in its original stifled form, our Ape has had a couple of twiddles to make its use more tolerable. The exhaust system has been replaced by an upswept twin-megaphone set to get rid of the asphyxiating catalytic converter, and the intake bore hole of the air filter box opened out so the inlet is no longer gasping through a tiny restrictive hole and, though still fitted with it’s original ‘very small’ carb, these simple changes are reportedly enough to deliver a ‘50% improvement in performance’!

Wheels comprise pressed-steel rim halves which are bolted together on cast alloy hubs, with a drum brake at the rear and 260mm hydraulic disc up front.

The bike wears telescopic forks up front, with monoshock rear suspension riding on a fabricated alloy box section swing-arm. All very modern and technical specifications, but it does look heavy, and certainly feels about as heavy as a dead water buffalo, so we roll the Zhenhua over the scales, 6 stone 2 pounds front + 7 stone rear = 13 stone 2 pounds, which sure is a lot of dead-weight for a 50cc motor to be dragging around!

Tyres are 120/70–12 with a block trail tread pattern that gives a rough ride on the road. Running at low speed on smooth tarmac felt more like riding on cobblestones.

Though the bike may look as if it’s going to deliver very adequate power, when just pulling off it becomes fairly obvious that the motor really is only 50cc, and the rider is likely to be requiring all of what the engine can give for most of the time. One shudders to think how dull one of these might be in original restricted format.

Comfortable cruising speed is found around 30mph, with up to 40mph achievable on the flat, and best downhill pushed the needle round to the end of the 45mph/70km speedo.

Having a front sprocket conversion to gear-up the drive ratio delivers better cruising pace and a little better top speed, but comes at a cost as the motor fades on inclines in top due to the engine’s lack of power.

Obvious complaints are that the footrests are too small to comfortably get your feet on. Rear braking was particularly poor, and only worked with lots of pressure on the foot pedal. The small fat tyres with their block tread pattern made cornering a bit vague, and proved somewhat prone to tram-lining on rutted surfaces.

The custom conversion split-mega exhaust produced an embarrassing and offensive overly loud drone that would cause most conscientious riders to back off the throttle in urban areas, and when held open outside built-up areas, the noise could easily drive the pilot crazy.

A Zhenhua Ape in standard 50cc restricted form would probably feel very overweight and underpowered, and we’re not entirely sure whether this 50cc model is even still being offered by the manufacturer. We do note however, that a seemingly identical ‘Ape’ machine fitted with a 125cc motor is being offered instead. Probably a good idea for an engine capacity that’s more capable of hauling this overweight cycle chassis—but not so good if you’re only 16 and limited to just 50cc.

Next—Our rocket blasts off and away from Planet of the Apes, up toward western space ... but somebody forgot to fill the tank, so the fuel gauge shows empty and we might not get quite as far as we hoped.

Our only thought as we hurtle back towards Earth is where we may come down next?

It looks as if we might make somewhere in Eastern Europe ... what’s that body of water in the distance, the Adriatic? No! We’re falling short, behind the Iron Curtain; please don’t let it be ... what could possibly be of any mopeding interest in ... Yugoslavia?

This article appeared in the

October 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2013

M Daniels.]

Planet of the Apes was an epic follow-up article that was already in the planning before publication of its preceding Monkey Business feature in July 2009! How could this be? Simple, the Zhenhua Ape was road-tested and photoshot back in May 2009, at exactly the same time as the blue Dax in Monkey Business.

Julian Bocsi’s blue Dax made the cut into the original article, while his Zhenhua didn’t find space and got held over for the follow up—which wasn’t destined to happen until over four years later!

Things finally started stepping up on the Planet of the Apes article when we managed to bag Brian Wales’s Gorilla just after the Radar Run in early April 2013, followed by a total rush of blood as Paul Daniels’s Dax came in for road-test & photoshoot with the cuddly monkeys later in the month.

Four years in the planning, and it almost seemed as if we could see the finishing post, three bikes down and only one more to go to make up the same number as the original monkey feature.

Mick Cook had completed rebuilding the Chaly, even running it at an earlier event in the year, only to experience gearbox and performance issues with its first XY 140 engine. Attempts to resolve the technical problems were finally concluded when this first new ‘nothing-but-trouble’ engine completely dropped its gearbox and became largely consigned to the spare parts bin after only a few hundred miles.

Meanwhile, we’d already written the new monkey bike feature into the leader from the Indian AMI50 Chief article of last issue, so IceniCAM had committed to running the Monkey-2 presentation just shortly before the Chaly lost its gearbox—which created a little more unplanned excitement than we might have cared to add to the feature!

Fortunately, Mick didn’t mess around, and consequently replaced the problem motor by another brand-new and much better example of the same make, then went through a further number of fine tuning and technical tweaks to iron out the bugs, and the bike finally began to perform as intended.

Chaly’s last-minute road-test and photoshoots were rushed through mere days before the editorial deadline at the end of August, and the text file only completed write-up in a day long and overnight session 28th to 29th August.

The final ‘Barbie’ covershoot only took place on Thursday morning 29th August, so talk about running right down to the wire!

And you might ask ‘Who is Hairdresser Barbie to ride this crazy Honda Chaly?’

Well, it made a good story, but was all just fiction, and Barbie doesn’t really exist. The photoshoot was taken with Rachael Fox, who previously did our Clark Scamp photoshoot back in July 2007.

Costs to produce our Monkey-2 feature were pretty minimal since the bikes were all fairly local and tested along the way. We’d also like to say that no monkeys were harmed in the making of this feature, but they were ... apart from all the problems with the Chaly exploding its first engine, the Gorilla suffered a broken kickstart ratchet right after the test, so don’t go thinking that these features all go smoothly—because they most certainly don’t!

The frame and swinging arm were presented to Knurl at ‘Walton Works (North)’ having been blasted and etch primed by Steve Last (one of the driving forces behind The Coasters scooter club).

During initial preparation this coat of etch primer was found to be very thin, and much of it was rubbed through while preparing the surface with 240 grit abrasive paper.

Two subsequent coats of two-pack etch primer were applied, followed by three coats of high build acrylic primer. A black guide coat was gently dusted over the entire surface and allowed to cure fully.

600 grade wet & dry paper was used wet, with copious amounts of soapy water to remove the black guide coat. Employing this method ensures that every imperfection is highlighted and can be dealt with accordingly. Once all of the guide coat has been removed, you can be assured that the remaining surface is smooth, flat and free from imperfections. This approach may seem unnecessarily long-winded, but the most common mistake made during any painting process is to underestimate the importance of thorough preparation for colour coats—any minor imperfection at this stage will only be compounded as further coats are applied.

After a thorough cleaning and degreasing, the frame and swinging arm (subsequently replaced by alloy box section swinging arm), were treated with three coats of Harley–Davidson Silver & Aluminium base. This particular base coat has an unusually high brilliance, and has a high concentration of large metal flakes, making it perfect as a substrate for the three subsequent coats of Harley–Davidson ‘Candy Brandy Wine’.

Candy colours are highly pigmented and are semi-transparent, so the base paint shows through. This is what affords them a brilliance and depth of colour that can’t be achieved with a solid or traditional metallic paint.

So, eleven coats of paint applied so far, and a result is starting to show through! Minor dust and imperfections were very carefully removed at this stage—if you’re too heavy-handed with abrasive paper at this stage, the base coat will show through as a lighter hue, ruining the finish which will be impossible to replicate without starting again from scratch, so it’s seat of the pants stuff.

Because of the need to get into all the intricate shapes of these panels, a small gravity fed detail gun was used, with a 1mm fluid cap set-up. This is usually the weapon of choice for projects of this size, as it’s small and light in use.

The next stage was something of an experiment, not having sprayed metal flake before. The detail gun was dispatched in favour of a full size suction feed gun with a 1.6mm set-up. Two pack clear lacquer was mixed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and a ‘slack handful’ of large dark gold metal flakes were thoroughly mixed-in.

50PSI on the regulator, extraction fans on full power and the trigger was gently squeezed—a brief hiss from the business end of the gun followed by ... nothing! The metal flakes had completely clogged the fluid cap, much as rust flakes from a rusty fuel tank will clog a fuel filter.

The gun was unclogged, set to one side, and substituted with another full size, gravity fed gun, this time with a 2mm set-up, more suited to industrial coatings than a delicate effect on a moped frame.

After the metal flake laden lacquer was transferred to the clean gun and yet more thorough mixing, the pressure was taken up to 65PSI to compensate for the increased air consumption of the larger fluid needle set-up, then with breath held and fingers crossed, the trigger was gently squeezed. To great relief, a jet of speckled lacquer issued forth, coating the frame, swinging arm, workbench, floor, ceiling, tools and indeed everything else in the vicinity!

Light coats were carefully applied until a sufficient saturation of flake effect was achieved over the entire surfaces, making sure that a consistent depth was maintained all over.

Guns were cleaned yet again, and three further coats of two-pack clear were added ‘wet on wet’, meaning that the coats with the glitter were only allowed a short time to ‘flash off’ the solvents rather than being allowed to fully cure. This method can introduce runs and sags, but means that there is usually less opportunity for contamination between coats. It would also have been impossible to rub-down the glitter coat without damaging the glitter.

These parts were then set aside for about a week to achieve full cure, then rubbed flat with 1200, 1500 then 2000 grit wet & dry, again used wet with plenty of soapy water. Using papers wet helps to prevent them clogging, which will scratch the surface you’re working on—ironic that an abrasive paper can introduce unwanted scratches!

This is a long and laborious process, but if it’s rushed the end result can look compromised and inconsistent. If you’ve spent this long on a project, why cut corners at the last minute and undermine all of the preparation you’ve put in so far?

When cleaned and dried the surface will look dull and lifeless, but if you’ve done the job properly it will be uniformly dull, and free from deep scores or scratches. The next step is the most perilous but also the most gratifying; buffing to a deep, wet looking shine.

This is another slow and painstaking process, but with a combination of a dual action, low speed polisher and open-cell buffing heads of various grades, used with the appropriate grades of cutting compounds (I used two different heads and four different compounds) a spectacular transformation happens. When you wipe the first section clean and give it a rub with a clean soft cloth you’ll be greeted with a smooth, lustrous finish with a depth of colour that can only be achieved with patience and perseverance. All you have to do now is repeat these steps over the entire surface, switching to often stubbed fingers in the hard to reach places.

A final wash to remove the remaining rubbing compound, three coats of a good quality carnauba wax and the parts were ready to go back to ‘Walton Works South’ for assembly. Total time taken: somewhere in the region of 25–30 hours.

The other parts were much simpler—wheel hubs, fuel tank, various brackets and mudguards were suitably prepared then aerosol painted, then given two or three coats of two-pack clear to give them the desired finish and protection.

You don’t necessarily need to take 25 hours to achieve a top notch finish on a frame and swinging arm, but always remember that 80% of the end result starts with what goes under the colour coats—only 10% of the finish is applying the colour and the remaining 10% buffing and polishing.

My advice if you want to ‘have a go’: always work in a well ventilated area, wear good quality breathing protection, and most importantly unless you want a work area that looks like Santa’s Grotto never, ever, ever use metal flake!