Walking along Summer Hill Street in Birmingham, we catch a glimpse of an old copper coin in a corner of the pavement. ‘See a penny, pick it up, all the day you’ll have good luck’. We sit on the low wall to examine our find, and rubbing off the dirt, Britannia bears the date 1903—over 100 years old! The Black Queen only deceased the preceding year, to be succeeded by King Edward VII and, turning it over, the coin wears his head. Since big old pennies flick so much better than the little modern coins, we can’t resist tossing our prize, watching it spin in the sunlight.

Staring intently as it tumbles through the air; the rotations seem to slow, focusing only on the coin as the world becomes a blur, before finally catching in our palm and slapping on to the back of our hand.

‘Heads or tails?’

It’s tails, and we’re back in 1903…

Crossing the road over to Parade Mills, we walk down to an industrial building ‘numbers 29–35’, and founding office of The New Hudson Cycle Co Ltd.

Like several other bicycle manufacturers, the firm went on to add motor cycles to its production in 1909, using both proprietary motors, and engines of its own manufacture. The New Hudson marque was first represented at the Junior TT in 1911 and moved up to the Senior TT in 1914. Like many other makes, production was interrupted by WWI, but resumed again in 1919 from new premises at St George’s Works, Icknield Street, Hockley. By the 1920s New Hudson was back to racing, and at the middle of the decade the motor cycle range impressively extended to 12 models from 350cc to 600cc.

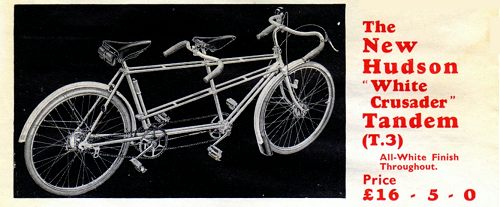

The White Crusader—a New Hudson tandem

of the 1930s with an unusual duplex-tube

bolt-together frame design.

The 1930s brought an ebb tide, as the effects of the great depression reflected in a progressive reduction of New Hudson’s motor cycle range and a lack of any new models for 1933. It was indeed a bad sign, as production became suspended the following year, but the firm continued manufacturing its bicycles and making brakes and suspension units for Girling.

While general industry slipped into recession, conversely, the cycle trade was booming! Several motor cycle manufacturers temporarily sought refuge from the commercial storm in this port, and the period found some rather unlikely names appearing on pedal cycles: AJS, Matchless, and even Francis–Barnett! New Hudson probably weathered the 1930s better than suspected, since during this time its catalogues illustrate some remarkably innovative frame designs.

Despite the developing distraction of WWII, New Hudson managed the somewhat belated introduction of its first autocycle in March 1940. This was a typically basic machine with rigid frame, cycle forks, and powered by Villiers JDL motor. Events quickly overtook commercial concerns, and production was suspended during the same year.

While many businesses would fail to return after the war, some were developing from the situation. One such very good example was Birmingham Small Arms, who acquired Sunbeam in 1943, Ariel in 1944, and took over New Hudson before the end of hostilities. To meet the new peacetime opportunity for economic transport, several manufacturers simply returned their pre-war models to immediate production—and the only established autocycle design within the BSA Group was the New Hudson, so it was taken off the shelf, dusted down, and put back on sale for 1946 … which is pretty much where our first feature machine comes in!

Frame number M3020 with its original registration date recorded as 22 May 1945: only a matter of days following the German surrender declaration by Admiral Dönitz! This is a wonderfully honest and genuine example, very weathered, but largely original and unrestored. There is no decompressor cable between the handlebar lever and the valve in the cylinder head, so it takes a little more pedalling effort to get the engine turning over, but the motor fires up readily enough so it’s not much of an issue. With a jet of smoke shooting into the middle of the road from the cross-pipe at the outlet of the alloy silencer box, we trundle away from the scene of the environmental crime.

It quickly becomes obvious that the most comfortable cruising pace is below 20mph, since vibrations come in through the pedals above this, which at some speeds are so bad that the rider is driven to lift their feet from the pedals for relief! Despite the lack of suspension front and rear, the NH-JDL rides quite reasonably, and the steering geometry is correct enough to even allow riding hands free with confidence—it holds a steady course!

Flat speed with a tailwind achieved 29mph, and the best we clocked against the pace bike was 33mph downhill, then from the bottom of the dip, the bike slowed to plod up the other side at 15mph, but at no time was any pedal assistance required. The limited brakes matched the limited performance, proving adequate for general slowing down, provided nothing spectacular was going to be required from them.

This ancient New Hudson rumbles and clonks along with its JDL motor, very much giving the impression of some agricultural device, though the handlebar set provides a comfortable traditional riding stance in a most classic English posture for our ride on this early rigid autocycle. It’s a very likeable machine for its honest and functional simplicity, and a nicely restored example of this model would probably become the delight of any owner.

The pre-war model was listed through the season of 1948, when Villiers informed its autocycle engine customers that the JDL motor was due to be succeeded from the next year.

New Hudson was straight in the market for 1949 with a new model for the new 2F engine. The new frame series coded from ZE101, and would go on to register over 10,000 units by 1955. The only significant identifying change to machines over this period was a switch from the ‘black with red tank panel’ colour scheme 1949–52, to ‘dark green/cream panel’, or ‘maroon/cream panel’ 1952–56, though different mudguard patterns may also be noted.

Our first featured New Hudson 2F is red & black PVW 937, first registered on 5 April 1950. Initial impression is a spectacular and detailed restoration—these autocycles were never this showy! The polished brass shell Lucas headlamp was certainly no original fitting, but complements very nicely. The bike was run with side-panels removed on the test day to illustrate the 2F engine for the photo-shoot. This example retains the lever-operated throttle, but to further complicate control operation, the spring on the clutch lever fails to return the latch, so needs to be engaged by secondary finger movement. The inherent awkwardness of the inverted brake lever combination is not helped by the clutch lever being positioned above, and obstructing access to, the reversed arrangement of the brake lever on the left operating the practically useless 3½" front drum. The inverted rear brake lever on the right bar proves heavy to operate (nylon lined sleeves would really help on these long cable runs) and equally ineffective at retarding motion.

The engine starts readily, exhibiting an aggressive exhaust tone, with a little four-stroking initially, which decreases as the engine warms. It’s also very apparent right from the off, that this bike has a very strong motor—it pulls like a train! Oh great, a fast bike with rotten brakes; it’s either ride it like granny going shopping, or just go for it! Read the road, pick confident lines through the corners, and you can quite hustle this New Hudson along: pace bike clocks 35mph on the flat, 38mph downhill—‘and by the way, it’s running in a new 105cc rebore’ … ‘Err, that’s OK, I took it easy!’

Originally registered in September 1952, our second new Hudson 2F autocycle, 712 UXB in green & cream, starts up quite readily, and immediately advertises a similar noisy exhaust note to its predecessor. The twist-grip throttle on this example makes controls slightly easier to operate than some other autocycle arrangements, though having the clutch lever position set above the brake does obstruct access to operate the rear stopper. Despite this handicap, the rear brake proves reasonably effective for an autocycle, and the 4" front drum proves pretty fair too.

The engine pulls steadily as the motor warms up around our test circuit, and the Hudson lumbers up to a happy cruising speed about 25mph. You are very conscious all the time of the noisy exhaust and constant four-stroking, and become grateful for inclines and head winds that make it pull cleanly and provide a break from the staccato firing. The condition slightly improves as the engine gets hot, but the four-stroking remains ever present and quickly wears you down.

The recently refurbished Webb girder forks were nicely reactive up front, doing their job ahead, bobbing away enthusiastically and smoothing out the road, though handling feels generally cumbersome and barge-like, requiring a confident and committed line through corners if they are to be taken at any pace. A change of course halfway through or hesitant touch on the brakes, and it feels unsure quite where it wants to go—clearly not built with sporting geometry! Best recorded speeds were 33mph on the flat and 36mph downhill (four-stroking occurring).

Completing the course, we whip out the spark plug, and sure enough, black and oily. Despite the spirited pace, this engine is clearly running rich, and a likely contribution to much of the irritating four-stroking. Carburettor tuning in this case would probably provide improved performance—and economy!

This example exhibits a partial ‘essentials only’ restoration, and while some components have obviously been replaced or improvised, there are also many other original features retained. Looking round the rest of the bike, you have to love the 4½" Miller headlamp with its beautiful classic fluted glass as a nice change from the usual VEC flat-backs that generally adorn most autocycles. The Miller is properly mounted on its correct bracketry too! We like that those chunky and original John Bull pedals are still fitted too. Also worthy of note is the light gauge, solder jointed pedal chain-guard, clearly illustrating New Hudson’s cycle based primary business.

The different lamps look smart on both these examples, but you really wouldn’t want to depend much on autocycle lights at night, the output of the 12W generator doesn’t go a long way, and if you find someone flashing you on a dark country lane—it’s probably not because you’re blinding them! Though both these 2F models ostensibly look the same apart from the paint job, it’s actually not the case. We noted the front hubs were different sizes, but also New Hudson completely changed the lug arrangement on the lower frame, resulting in different stands, and one often observes different mudguard patterns too.

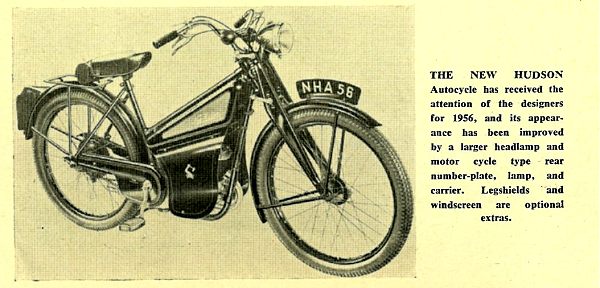

Into 1955, New Hudson started phasing in a number of new fittings as ‘official’ transitional models with various combinations of the Miller headlight, tubular fork set, press-formed rack, and the rear number plate. Legshields and a screen were also posted as extras for these models.

The ‘transitional’ model New Hudson is announced in November 1955

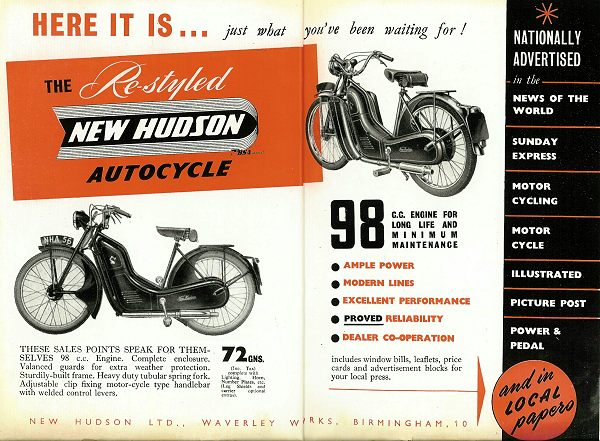

The next evolution was introduced from May 1956 and represented the only second generation 2F autocycle made by any manufacturer. Launched by New Hudson as the ‘Re-styled’ autocycle, over time, this machine has also come to be called the ‘lady’s model’. It actually represents quite a radical re-design of the cycle chassis with a low step-through frame, and petrol tank, engine shields and chain-cases blended together into one continuous form. Though rather odd looking, the result is plainly practical, easy-clean, and probably some consequence of scooter styling influence. The Webb blade forks are replaced by Webb coil sprung tubular girders, gone is the typical ‘flat-back’ headlamp, succeeded by a cone shell Miller with VDO speedometer kit listed as an extra at £4–8s–8d. Mudguards feature partial deep valances to improve weather protection, and are sweepingly styled to blend with the bodywork. The traditional tubular autocycle long rack with flat letter plate and cycle rear lamp have fallen from favour for a motor cycle styled number plate with dedicated pattern Miller lens, and the press-formed carrier (listed as an extra at 14s–6d, though little more than a shallow trick to keep the basic price down, since the rear mudguard would be unsupported without the rack fitted). Colour was generally given as ‘maroon/gold lined’, though ‘green/gold lined’, and ‘black/gold lined’ trimmed examples are occasionally seen. Legshield kits and a screen also continued to be listed available as extras.

New Hudson introduces the Re-styled model

to its trade customers in April 1956

The Re-styled frame series began from N1001, with N4880 being the final listed in Glass’s Index. Our last feature machine displays frame number N4629 and, though repainted in ‘black, gold lined’, it has been restored in this original finish. Despite the panelled look, all the controls are quite familiar, except that a twist-grip throttle has replaced the lever control. There’s a small port in the left hand engine cover, allowing access to operate the choke shutter and carb flood button—but nothing obvious leading to any fuel tap? It really is pretty well hidden, and proves even more concealed by the leg-shield set, as it’s finally discovered hiding under the front right side of the tank as you grope between the fairings to ‘pull on’ the Ewarts plunger.

Finally, we get the Re-styled fired up, with as much smoke blasting forward from the silencer joint as trickles from the tailpipe. It’s fitted with one of those pattern exhaust systems that’s so stifled, you have to wonder if any gas is escaping at all! No wonder it’s trying to get out at the pipe joints! All the new exhaust chrome is nice and shiny, but the poor thing’s suffocating!

Ignoring our mount’s muffled suffering we twist on the throttle to wind up the revs, and feed in the clutch. This motor has plenty of urge, and easily overcomes the high single gear ratio for an unassisted take-off!

I’ve heard many pilots of the ‘Re-styled’ model saying how well they ride, but this was the first opportunity to actually try one myself, and have to say—it really does handle very well indeed! The ‘odd’ design probably leads to a poor expectation, but it naturally flows through corners in a manner that few other autocycles can ever approach, while the stout sprung forks ride the road surface effectively.

Performance was also impressive, with the pace bike recording 38mph on the flat with a tailwind, and scratching 40mph downhill. I was beginning to wonder if we’d ever see the day of an autocycle with brakes that actually seem to work, but this is probably about the best yet! Unsurprisingly, there is the expected downside of panel resonation from the all-covering tin-ware, and a rather unpleasant level of noise from the motor reflected back by the leg-shields, and if a situation demands some roadside fettling, you’ve got all the armour plating to remove before you can get at anything. The updated front and rear lamps are, however, still supplied from the same old Villiers 12W mag generator set—switch them on and the illgloomination is comparable with a candle nightlight!

By the time the Re-styled came out in May 1956, it practically had the whole autocycle market to itself, most of the competition having previously withdrawn from the field. A dying breed, all else that remained was the veteran Norman Model ‘C’ original design from 1949, which soldiered on until May 1957, and the eccentric Cyc-Auto now only now produced in ‘hobby’ quantities. New Hudson had the last years of the autocycle pretty much sewn up!

The reason for its final demise in July 1958 wasn’t from BSA withdrawing the bike, but actually Villiers discontinuing the 2F motor unit due to its falling demand. The last dinosaur was dead, slain by the all-conquering moped, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II.