Everyone will almost certainly associate this company with large transverse V-twins, or depending on your generation, maybe hulking 500cc horizontal singles cluttered with complex detail. Carlo Guzzi and Giorgio Parodi founded Moto Guzzi at Mandello del Lario in 1923. They built lots of motor cycles up to 1963, when the traditional motor cycle range was joined by an unexpected diversion: a 50cc Dingo moped! The original pedal design was by Antonio Micucci, but the old dog started learning new tricks as the engine carried the Dingo name on to other tubular framed kick-start sports variants by the mid-1960s, and Guzzi even showed a 50cc twin in the same chassis at the 1968 Salon de Milan, but that prototype never made it into production.

Our mangy old dog came in for some work, but being a little unusual, we thought the chance too good to miss, so took another opportunity to grab a quick mini-feature.

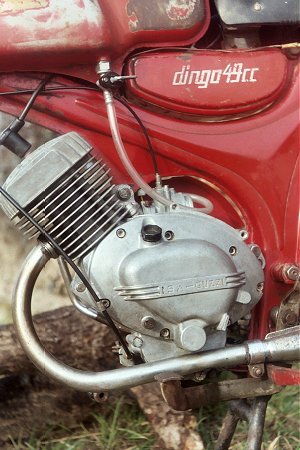

Dingos are pretty obscure in the UK, and this one’s on a foreign plate with no supporting documentation; The registration A 122477 is a Spanish one from Alicante and dates from 1967. The side panels are tagged as 49cc, but when we have the motor down, the piston looks suspiciously large, so out with the callipers, to measure 46.5mm bore with a 44mm stroke, which calculates to 75cc! The cylinder has a chrome liner, and doesn’t look like any after-market conversion. When we find the frame number on the headstock, it prefixes MGH-D75, so it certainly looks like a genuine model, though it doesn’t appear in our list.

| Dingo Turismo | 1963–66 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo Sport | 1964–65 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo Super | 1967–69 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo Cross | 1967–69 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 17" wheels |

| Dingo GT | 1967–70 | 48.9cc | 4-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo 49M | 1969–73 | 48.9cc | 4-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo Cross Nuovo | 1970–73 | 48.9cc | 4-speed | 17" wheels |

| Dingo Super Sport | 1970–73 | 48.9cc | 4-speed | 18" wheels |

| Dingo 50MM | 1970–75 | 48.9cc | 4-speed | 16" wheels |

| Dingo 62T | 1972–73 | 62cc | 4-speed | 17" wheels |

| Dingo MM | 1975–76 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 16" wheels |

| Dingo 3V | 1975–76 | 48.9cc | 3-speed | 16" wheels |

1970 Dingo

The fitted IRZ carb has a tiny 8mm bore, so we’re not expecting any spectacular performance, but it does provide some clue to our bike’s origin. Italian Moto Guzzi models were typically fitted with Dell’orto carburettors, but during the late 50s, building of some small capacity two-stroke motor cycle models became licensed to Motor Hispania in Spain. These machines were branded as Moto Guzzi Hispania models and were characterised by a number of different fittings, typically IRZ carburettors, and Femsa Spanish ignition sets in place of Italian CEV systems. The MGH frame prefix would seem to confirm this, and since these Dingo 75s predominantly appear in Spanish sales, one may conclude it is likely to be another Motor Hispania licensed product that was probably never exported, and only sold into the home market.

All this means our Dingo is definitely a Spanish made version: we’re going to need a different list.

| MGH Dingo | 49cc | 1965–66 | |

| MGH Dingo II | 49cc | First Series | 1966–67 |

| MGH Dingo II | 49cc | Second Series | 1967–72 |

| MGH Dingo Blanca | 49cc | Gran Turismo | 1969–70 |

| MGH Dingo | 70cc | 1966–67 | |

| MGH Dingo | 75cc | 1967–72 | |

| MGH Dingo | 75cc | Ranchera | 1968–72 |

| MGH Dingo | 49cc | Ranchita | 1970–73 |

| MGH Dingo S | 49cc | 1971–73 | |

| MGH Dingo Sevilla | 49cc | First Series | 1974–75 |

| MGH Dingo Sevilla | 49cc | Second Series | 1975–79 |

| MGH Dingo Serva | 49cc | 1975–79 | |

| MGH Dingo Campero | 49cc | First Series | 1974–75 |

| MGH Dingo Campero | 49cc | Second Series | 1975–79 |

And there it is: A Moto Guzzi Hispania Dingo 75cc from 1967, and the only remaining mystery is why it says ‘49cc’ on the side.

The pressed steel and seemingly ‘Sports’ styled chassis is actually based on the very same moped frame, and neatly transformed by the slim motor cycle tank, dual seat, and add-in toolbox to fill the gap. The conversion works well, and most people unfamiliar with the model would never guess.

To match its sports motor cycle style, the engine is kick-started, with transmission through a 3-speed gearbox. The foot change selector is a bit unusual, in that it is not integral with the engine, being a separate built on fitting. That figures, since the original moped started life as a cable operated hand-change.

There’s no battery on our Dingo, and no key so, just like a moped, it’s kick and go.

The kick-start operates in a forward action, as a carry over from its moped origins, and the ratio barely turns the motor over twice in one stroke. The engine however proves easy to start, just turn on the fuel tap, flood the carb, a little tweak on the throttle (not too much or it kicks back!), a couple of jabs and our wild canine fires up straight away! The snarling exhaust note is fierce and aggressive, it suits the name of the bike alright—but may not be a tone that everyone takes to.

Dingo Cross

We try the lights before setting off, they all work, but dimly, and may not be helped by a 12V bulb in the back. The electrical cut-out doesn’t appear to work since we can’t stop the engine on the button, but then again, that may be the horn, which doesn’t seem to work either!

The foot-change operates with a light action, as one down for first, then two up for second and top. Though the Dingo initially impresses with quite a torquey feel, its ability to accelerate is limited by difficulty of access to the gear lever, which is tucked away under the motor so as to clear the forward action kick-start. A further handicap is that the toe pin on the gear lever is also so far forward that you cannot reach it without having to take your right boot off the footrest. Obviously little thought went into the change arrangement—or maybe the designers were clowns with long shoes? The clutch works well and the lever is light to pull, and when you’ve finally managed to find the gear lever by invariably having to look down for it, the gears shift and engage very well.

There’s some noticeable mechanical noise from the motor, which presumably comes from the gnashing of primary drive gears.

With the torquey feel at low revs, you expect the Dingo to get up and howl when you screw open the throttle; the motor certainly feels like it wants to—but not with that 8mm carb it ain’t!

Though the forks are hydraulically damped and very firm, handling is not confidence inspiring, being prone to tramlining at the front, but perhaps new tyres might help. The rear suspension units are undamped, and seem rather bouncy at the back, but don’t appear to affect the solo ride since the pilot sits ahead of the shocks, though how this may behave with a pillion passenger aboard could be a different matter.

With the wind behind us, the pace bike clocks Dingo’s best on the flat at 35mph, while our speedo reads about 55km/h. Labouring into the headwind our 90km Veglia falls back to around the half-way mark while the pace bike reads us off around 30mph. Downhill, Dingo’s dial reads around 65km/h while our pacer checks us off at 39mph.

Going back uphill on the other side, the speed readily falls away, and we have to cog down to second to make the brow.

Despite being 75cc, our mutt proves all bark and no bite! The 8mm carb well and truly muzzles it. Dingo lacks power when you need it most, headwinds and hills are times when you need to turn the horses on, but our doggie just rolls over and plays dead.

On the flat, it’s not so bad and lopes along steadily enough, though feels almost like being overgeared since the motor can’t get up and buzz due to the tiny carb. On the plus side, at least you know the engine is unlikely to have been revved to death!

Both brakes are very effective, but the front one squeaks loudly in use.

People who dropped round to the workshop while Dingo was in the pound, quite liked the unusual ‘groovy dude’ 70s’ styling and ‘razor blade’ look of the slim tank and sporty seat (that’s so firm it’s like sitting on a board).

Dingo rides rather like a sports moped, but with just three gears, and the 8mm carb, its performance is more comparable to a fifty, than its actual 75cc.

Prototype twin-cylinder Dingo, 1975

As the ‘old guard’ retired from the stage, in February 1967 the Moto Guzzi Company was sold to Seimm, who revitalised the flagging business with introduction of the now familiar transverse V-twin motor design, and an expanded range of low priced Dingo and Trotter models to appeal in the utility moped sector.

Seimm was acquired by De Tomaso Industries in 1973.

In 1988, Fratelli Benelli and Seimm merged to create Guzzi Benelli Moto (GBM SpA), though this resulted in the Benelli plant being sold off, and the closure of Innocenti. Despite the cutbacks, the group was stumbling along in the red again by 1993, so the following year, De Tomaso Industries handed control to Finprogetti. By 1996, operations were back in the black, and the name changed back to Moto-Guzzi SpA, while the Argentinean Industrialist, Alejandro De Tomaso, withdrew from the business during the year, so De Tomaso Industries assumed the name of Trident Rowan Group.

On 14th April 2000 Moto-Guzzi was taken over by Aprilia SpA, and in December 2004, the final acquisition signed Aprilia Moto-Guzzi over to Piaggio Group, forming Europe’s largest motor cycle manufacturer.

Motor Hispania continues to produce small capacity motor cycles, and has for some years been exporting a number of models to the UK.

Next—The support article comes back to England to mini-feature a moped from a famous manufacturer of horizontal flat twins, yet in the interests of continuity, also manages to naturally follow on from the features of IceniCAM 6, and still retain links to the Iberian Peninsula! What can it be?

This article appeared in the July 2008 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2008 M Daniels.

Montage © 2008 A Pattle.]

Doing the Dingo as a support feature was a very different epic from The Wasp and the Bee, after David Freeman bought it on Satan’s website of temptation. He’d spotted from the picture that the cylinder finning appeared unusually large for a 50, with the suspicions confirmed by a few simple measurements and a bit of maths—not 50, but 75. The bike came in for general sorting, which practically involved a complete strip and rebuild to get it running and representative. Being an interesting and unusual light motor cycle knocking on for 40 years old, it was easy to see the article appeal, so we agreed to do a feature before it went back.

Being a wild dog from the Outback, there was some thinking that the Dingo might warrant an Australian theme photo-shoot? Unfortunately, the ridiculously tight mini-feature budget of £6.50p for film, developing and CD didn’t quite stretch as far as covering the antipodean air flight and freight, so we had to make do with pictures on the edge of woodland outside the village, then cranking open the aperture to overexpose the film to try and make it look a bit like some sunburnt outback! We put a tin of Fosters on the ground for effect, but it still seemed to lack something—then Dawn said it was a pity we couldn’t get a stuffed crocodile!

Yes, it was another bit of digital trickery, but it certainly made everyone smile!

The Dingo all tied in nicely with the common theme for edition six of the magazine, since Piaggio now also owns Moto Guzzi.

Collecting the sponsorship credit on the Dingo is Terry Stollery, modestly represented as ‘just an IceniCAM reader’!

| CAMmag Home Page |