Today, we thought we’d take a break from all the hectic time travel, and pop out for a little Italian. Well, two actually, and though both vehicles were both 50cc, and made by the same company, they are just about as unalike as chalk and cheese.

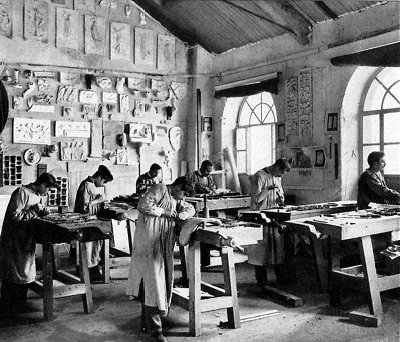

The ‘ship fittings’ made by Società Piaggio

were mainly decorative woodwork for the

saloons of passenger ships

Our featured manufacturer was founded in 1882, by Enrico Piaggio with his son Rinaldo, in Sestri Ponete, Genoa, as a Timber Stockyard. Rinaldo shortly left to set up his own branch of the business and founding the Società Piaggio in 1884 to make ship fittings. By 1900, the focus had shifted toward railway coach construction, and further changing interests found Piaggio building aeroplanes by 1915.

Piaggio’s ‘Paperino’

A change of direction was necessary after World War 2 and, with the growing demand for private vehicles, attention turned toward personal transport, the result of which was a prototype scooter nicknamed "Paperino" (the Italian name for Donald Duck). Piaggio was, however, not comfortable with the machine, so handed the project over for re-design by Corradino d’Ascanio.

In 1946, the first Vespa (translation—Wasp, derived from the buzzing exhaust note) scooter was marketed as cheap utilitarian transport, and became one of the most successful vehicles ever sold, continuing in production over 50 years later. A 50cc machine range was introduced from 1963, and Piaggio Group acquired the famous Gilera Company in 1969.

50cc Piaggio Vespa mopeds were first listed in the UK from 1968, in the guise of the Ciao. Marketing the successful continental image of a moped as fab and stylish just wasn’t going to work with the ingrained big bike and scooter culture in mainland Britain, so the Ciao simply fell into the general shopping basket of largely ignored basic commuter transport.

Moving along from the Ciao, but utilising much the same running gear in a different chassis, the Bravo became listed from July 1977. Our featured top-of-the-range Bravo EEVL is a particularly nice original example dated 1982, in excellent order, with only 1,200 miles on the clock, so should make a very representative test machine. Before closing in for the kill, we circle our prey to take stock of the intended victim! Telescopic front forks, with swing-arm suspension at the rear, firm 2.25×16 tyres on broad Agrati rims laced with stout 2.5mm spokes up front and very substantial 3mm on the rear, and the universal stock Italian pressed hubs—so we might expect it to handle and stop fairly well.

The frame comprises the typical period established bent length of large diameter tube from headstock to tool cartridge that slides out of the tail end. The flattened rectangular petrol tank is slightly unusual in that, instead of saddling over the frame, it fastens from below the tube, but all visually blends in, so no matter. The step-through frame is trimmed with plastic footplates to accommodate the continental feet-up riding style—I don’t think we’ll be having any of that nonsense here thank you!

The engine and running gear are very distinctly carried from the Ciao, 9:1 compression air-cooled alloy head, disc valve engine with horizontal fan-cooled iron cylinder, pedal chain drive on the right, and belt transmission on the left—so let’s pull off that plastic cover and have a look at the drive mechanism. Look at the length of that belt, that’s some fair stretch from engine to rear wheel! The front variator actuates on engine revs, and effects the sprung rear cone set, so delivers a smooth and automatic drive ratio change from low to high, by exactly the same system one sees adopted on the world-conquering scooters of the 21st century.

Behind the engine and in the middle of the engine plates, we know there’s a 12mm Dell’orto carburettor hidden in there somewhere. If you squint between all the surrounding stuff, you can occasionally catch brief glimpses of it—let’s hope we never have to service it! Comprehensive security is provided by all the latest that 80s’ technology has to offer—yep, it’s still the jolly old steering lock, and we actually have the key! Perhaps we could test the efficiency of this traditional anti-theft device by leaving it at the station car park for a day, and see if it’s there when we get back in the evening—err, better not!

Getting going appears pretty standard, fuel tap on, push the choke lever down under the right-hand footplate, little lever on the left bar works the decompressor, then push down on the pedal and, though the ratio feels rather high, the motor starts readily enough, and the choke automatically flicks off as the throttle is opened. Acceleration is pretty brisk, so the variator set certainly contributes well there, making the Bravo a useful about-town machine that should keep up with traffic pace from junctions.

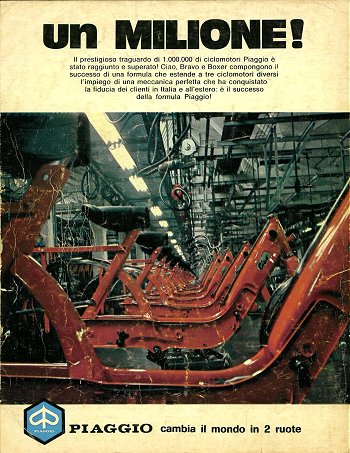

In September 1974 Piaggio advertised

that the Ciao–Bravo–Boxer range

had reached the 1,000,000 mark

Though the general handling proves confident and sure-footed, the saddle gives a lot of rubbery bounce, and coupled with the surprisingly long travel of the rear suspension units, on a bumpy road—it kinda feels like bouncing along on a Space-Hopper! Braking performance is directly proportional to how hard you pull on the levers, but however hard you pull, the wheels won’t lock up—so perhaps that means it’s got an early ABS system?

Spurred on by the challenge of the ‘Slo-ped’ frame plate, our smallest and lightest rider tucks into minimum sports crouch on a downhill stretch with tailwind, and is clocked off by the pace bike—What a result, 32mph! The test pilot goes home tonight, warm in the feeling of beating the system. "Max design speed 30mph—Pahh! That showed ’em!" (The 40mph Veglia speedo was apparently indicating 36/37 at this point, and we didn’t really have the heart to tell him!) Starship Bravo seems to generate some cyclic belt drumming effect as it approaches maximum warp, but back off a little and 25–28mph makes a much more comfortable cruising speed.

The headlight is a large, flat plastic box, with plastic lens and 15W bulb, while the tail lamp is 3W. The lights are probably a little better than their wattages might suggest, though we couldn’t really make out what was supposed to be happening with the 3-position switch, which had off in the middle and what is described in the manual as ‘parking light’ and ‘dipped beam’, which both seemed the same to us!

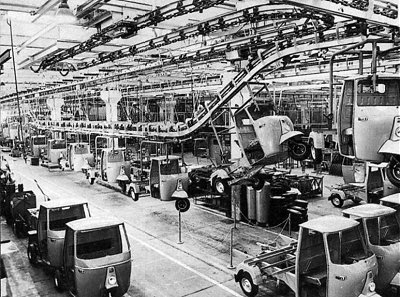

Following on the success of the Vespa, 1948 saw the introduction of what was to become another motoring giant, the Piaggio Apé (not as in monkey, but pronounced ‘Ah-pay’, translation—Bee). This time the new vehicle had 3-wheels, and was to have a huge influence on helping Italy’s recovery from Mussolini’s legacy.

Bajaj Auto rickshaw

The original scooter design with a box on the back, evolved into today’s Apé range based around a semi-monocoque frame that uses a single load bearing chassis in sheet steel, with a steel cab that houses either one or two seats. The body is available in a number of styles, including van, pick-up, and rickshaw, but also features further specific option versions for ice-cream vending, urban refuse collection, fish retail counter, insulated box van, plumber and service engineering equipment models.

There seems an equally extensive range of different engine forms available too, from 422cc European and 395cc (8hp) diesel motors, to a 150cc in the Bajaj Auto version licence built in India, right down to tiny 50cc powered machines, which is where our test feature vehicle comes in.

Dated as 1992, this imported machine had served a hard working life on the continent before restoration and recent UK registration. It started from humble beginnings as a 2-stroke 50cc model, but received a big-bore conversion somewhere on the highway. Along with general body restoration, the tired motor required a further rebore, and is now rated about 70cc.

Meeting the Apé, you are immediately struck that it’s actually a half-pint three-wheeler! Smaller than a Reliant, and those skinny little rear wheels look every bit of scooter origin. The pick-up back is plainly of very light gauge construction and, though obviously not particularly robust, it is of reasonable size and easily stows the Bravo moped on the back, still leaving space for another two or three of its brethren if the situation called.

When we arrive, our Apé pick-up is full of junk and hemmed in the side of the unit, so we empty it out and need to move the back over to thread it out through the workshops. Unlike the expectation of ‘bumping’ over a normal car, one person can simply lift the whole back end across in one go—it’s so light!

Now we can take stock of the cab, which seems as much door as cockpit, because it really is so compact… Are you sure there’s room to get two people in some of these? There’s a bench seat that crosses the width of the cab, so the driver would normally sit in the middle, but when joined by a passenger, you both have to sit at an angle on either side of the controls. While it looks as if the Apé might be operated from either position, it may technically be perceived that the driver would be in the right seat, since the foot brake is on that side. The floor of the cab feels so low hung that you feel as if your feet are going to be dragging along the ground, and as the door closes with all the structural confidence of a foil pie tin, you may suddenly discover a sense of claustrophobic apprehension that feels like it may be relieved by opening the window. This may not, however, provide the re-assurance you might be looking for, when you discover the side windows are only held closed by a wire spring, which you unsnap, and clip open at the bottom by locating the spring in a notch plate on the frame. Looking further up, the window hinges at the top, on a fabric strip riveted to the glass! You may like to sit a minute and marvel at the technology…

The controls may appear vaguely familiar to any scooter or geared moped rider, as a set of stem mounted handlebars sprout up from the floor where, from outside the cab, they steer a typical scooter styled front fork and front wheel. The bars are furnished with the usual twistgrip throttle and front brake lever on the right. To the left, a conventional lever clutch and 4-speed twistshift with neutral. Back braking operates by a typical scooter style foot pedal emerging through a slot in the floor plate.

The control arrangement in Apé really isn’t anything like you’d expect to find in any conventional car. Apart from the scooter handlebars, other controls appear almost randomly placed according to where it’s convenient, or where there’s space to put them. Pull out the choke knob underneath the seat, ignition key lock at the front of the cab dash, then electric start button on the handlebar, a twist of the throttle and the two-stroke motor blares into life. Then a couple of other levers each side of the steering column. Right is the handbrake, and left lever to engage reverse, then pull in the clutch for selecting the desired backwards gear on the twistshift—Oh horrors, yes, it really does have four reverse gears too, and will go just as fast backwards as forwards!

There are flashing indicators worked by a switch on the left handlebar, and a single (1-speed, slow) windscreen wiper, operated by a switch on the exposed motor. The windscreen washer is equally low-tech; you lift a plastic bottle off the parcel shelf, turn it upside down, and squeeze!

Having finished appreciating all the luxuries, and completed the pre-flight checks, we back out into the gangway, then forward through the cavernous workshops, and out the main door into the blazing sunlight.

Twist change into first, and in mere moments the engine is revving out—have we missed the gear? No, we are moving—barely! First is incredibly low, switch into second—more revving, 3rd—we’re on our way now, then up into top and open her up on the high road. There is a deafening cacophony of induction roar, motor noise, clattering suspension, and drumming panels—we must be doing at least 150 … but look out the window and the world is crawling by and there’s a queue of traffic behind! Best paced on the flat 31mph, 33 max downhill, and you can manage to hold it in fourth as it pulls back up the other side at 20mph.

Things sort of bounce around and twitch about, and you vaguely go in the direction you point it, but the experience isn’t really described as suspension or handling in any familiar sense of the terms. On bumps or turns, it feels as if the whole thing is going to fall over at the front. Brakes are quite effective, but they aren’t really dragging you down from much speed, and the pick-up back isn’t loaded on our test.

We bumble back to Sid at Felixstowe Motorcycle & Auto Centre, where he says our blue Apé pick-up with its new big bore kit is a veritable rocket-ship by comparison to his yellow Apé van with standard 50cc motor. The van is a little newer, and a little more evolved, with luxuries like internal plastic trim, and pozi-force oiling, so you don’t have to pre-mix the fuel anymore.

Though it proves less noisy and more civilised to operate, the lower engine capacity is immediately obvious. Acceleration and general performance are relatively equated against the bicycle, which will always beat you from junctions, but then you can usually manage to overtake once the speed has (eventually) built up to the maximum of 27mph on flat, and 31 downhill, while the lack of cc very much shows since we have to drop down to 2nd to crest the incline on the other side at 12mph this time.

Apé is like sitting inside a biscuit tin, with the performance of the slowest moped you’ve ever ridden, but can transport all sorts of stuff and will keep the rain off you. It will pretty much perform any tight turn that you can do on a motor cycle, so you rarely find the need to actually use reverse, and on tickover in 1st gear, it smoothly negotiates the tightest spaces at a mere trickle.

You might think of Apé’s natural environments as old Mediterranean trading towns with narrow streets and tight alleyways, or little villages with quiet country roads? Generally perceived as little more than a novelty in the UK, many other cultures across the globe have adopted them as economic and practical commercial vehicles for a multiplicity of roles in modern cities. Keeping a conscious eye out for them when away on holiday, you may be surprised at the places they manage to turn up, though back in Britain at our typical traffic pace, it’d be easy to perceive them as a major traffic hazard, and on dual carriageways—you’d probably find them squished and listed under ‘road kill’.

From humble beginnings, Piaggio rides on into the 21st century as Europe’s biggest motor cycle manufacturer, including under its portfolio of brands, Aprilia, Vespa, Gilera, Moto-Guzzi, and Derbi.

Next—Walking again down the corridor of time, the path ahead is crumbling … Just one foot wrong could plunge us forever into the autocycle time continuum. Whoops … we’re gone … falling … falling … to land in soft earth with a gentle thump!

What is this strange place, and why do all the machines here have baskets on the front?

This article appeared in the July 2008 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text © 2008 M Daniels. Bajaj Auto

rickshaw photograph © 2005 L Booth. Other photographs © 2008

M Daniels. Period documents and pictures from IceniCAM Information Service]

It’s rather odd the way some of these articles develop! The Wasp and the Bee started life as a simple mini-feature on the Vespa Bravo, which just happened to be quite a nice example that was passing through, so it seemed like a good idea to do an incidental item on it.

Then Sid at Felixstowe Motorcycle & Auto Centre got his blue Piaggio Apé pick-up sorted out and offered it for a road test. What a chance to put together two such contrasting machines from the same manufacturer! Then translating from Italian, Vespa = Wasp, and Apé = Bee, so what an opportunity for a great title! The pick-up offered bags of photographic potential with the moped in the back, and some of the ‘behind the scenes’ stuff you don’t get to see was quite amusing—like when picking up the Apé for road test, the garage Rottweiller decided he wanted to come too and ‘invited’ himself into the cab. It’s kinda ‘cosy’ in that little cockpit, with a steaming 12 stone Rotty on the bench seat, panting, slobering, and snarling at its reflection in the windscreen!

At least the pick-up was a discreet blue, but taking a liking to the Apé, Sid went out and bought the bright yellow van, so we had to do that too! Driving the little banana, the amused smiles of pedestrians just say it all as you scream by at 25mph.

So it was that the Vespa Bravo mini-feature became a main feature on Piaggio…

The cost of production probably broke all economy records for a main feature. Since it started as low budget mini-feature, the Bravo shots were all done in digital, so the same format carried right on through both the Apés too, so none of the usual film costs on this occasion, just a mere £10 for fuel. Sponsorship on The Wasp and the Bee was scooped up by Felixstowe Motorcycle & Auto Centre, so lots of thanks are due to Sid for helping get this article to publication.