KTM Hobby

In 1957, KTM presented its first take on the popular new moped market, in a ‘best-of-both-worlds’ interpretation the 50cc ‘Mecky’ was a single-seater scooter with pedals! There were several makes of similar hybrid scooter/mopeds made around the later 1950s, but their lack of continuation into the 1960s probably says everything you need to know about the success of the concept.

Moving on, KTM presented its somewhat more conventional Hobby automatic moped in 1968, which was released in different versions: the original 50cc ‘Mofa 25’ version was introduced with a rigid fork and rigid frame, then joined by other model combinations with telescopic fork & rigid frame, or telescopic fork & swing arm rear suspension frame.

On the continent, a Mofa 25 could be ridden without the requirement for a driving licence, but were restricted to a top speed of 25km/h (15.6mph). The engine was the Fichtel & Sachs type 502/1A motor with the usual Sachs 38mm bore × 42mm stroke specification for 47cc, and was simply restricted in performance by fitting a small-bore 8mm Bing carburettor.

An unrestricted automatic ‘Moped 40km/h’ (25mph) version was also offered. This had a larger 12mm Bing carburettor and was rated at 2bhp, but was classified under different regulations and needed a driving licence.

It was a logical progression for KTM to utilise a moped engine from fellow Austrian manufacturer Puch in place of the German Sachs motor and, in 1970, a Hobby II model was unveiled, now fitted with an automatic Maxi E50 motor rated at 2.2bhp. This ran in production alongside the original Sachs-powered Hobby, though the Puch-powered model never made its way to Britain.

KTM’s expansion had now brought it to the point of offering a range of over 40 models and employing a workforce of 400 personnel.

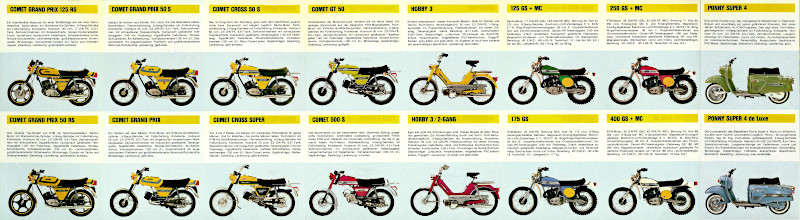

Part of the KTM range

Glass’s Index records that KTM imports to the UK resumed in April 1972, with the base model Automatic Hobby rigid frame moped, then joined by the four-speed Comet Cross sports moped from May 1973, and the Comet GT four-speed sports moped from July 1973.

Listed imports of the rigid frame Hobby ceased in November 1973, when it seemingly was replaced with the De Luxe Automatic Hobby with rear suspension, however our green K-registered Hobby Automatic De Luxe was UK registered in November 1972, so again we’re not so sure of the accuracy of the official Glass’s dating information in this case—and again it appears the De Luxe sprung frame model had actually been introduced earlier than suggested by the ‘official’ Index (our previous red Hobby registered in July 1972).

To a casual glance the KTM might appear a fairly similar style to its fellow Austrian manufacturer’s Puch Maxi, however the Hobby is very different animal.

A (missing) continental-style, cast-aluminium lifting handle is normally attached to the front of the seat post, which would be folded out for one-handed lifting in balance.

One puzzle is why, when Sachs went to all the trouble to produce the 502/1A ‘compact’ engine, they didn’t also go for lightness and make the cylinder barrel out of lightweight alloy instead of heavyweight cast iron? It just didn’t figure, and the bike feels quite solidly built for an automatic commuter moped, so we roll it onto the scales, and it’s 7st 4lb (46kg).

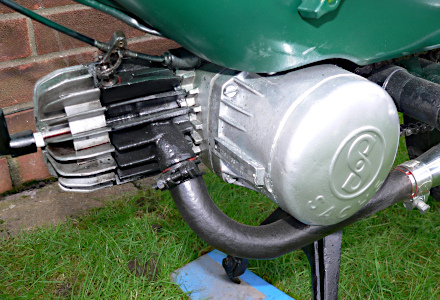

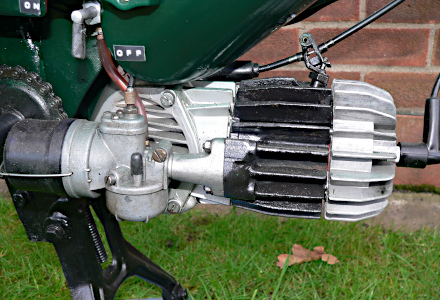

You may also wonder what might be so special about a ‘compact’ engine, and its trick is that the motor bottom-end is no bigger than the crankshaft! The crankcase is just a round cylinder with the top-end bolted onto one end, and doesn’t have any of the additional length of conventional motors that house primary reduction drives or a gearbox. The motor still needs a primary reduction drive, so how did Sachs get around that? Well actually, they didn’t—it just looks like they did! This is the moment you need to get your head around the engineering of what may be one of the most extraordinary automatic moped engines ever made: it’s got an epicyclic primary reduction planetary gear set!

After the crankshaft, in a line to the left of the motor, there’s the engagement clutch to start the engine, the centrifugal automatic clutch, then a planetary gear set, all within a thickness of just 10mm, driving out to the front sprocket, beyond which is the Bosch mag set.

It’s a fantastically engineered little motor, and all credit to Sachs for pulling off what nobody seems to have done before or since, but most of its riders would be completely oblivious of the trickery going on inside the motor—all they want is reliability and performance, and that’s where some of the shortcomings start to creep in.

The motor is built with an overhung crank, which dramatically limits its practical revs because the design becomes inherently prone to vibration as the revs increase. The inboard engagement clutch is operated by the same cable that works the decompressor, but, if you need to replace the cable, you have to take the motor out of the frame and strip the whole thing right back to the crankcase to engage the cable in the operating arm, unless you have the impossible skills of a keyhole micro-surgeon to do it through a tiny screw plug hole in the top of the case. For any normal human mortal it’s simply impossible!

There’s other weird stuff about the motor too, like the decompressor site in the cylinder head that Sachs left blank! Instead they put the decompressor into the sidewall of the cylinder and vented it through a hole 20mm down from the top of the bore! The Sachs ‘compact’ engine certainly looks futuristic with its single-sided appearance and radial finned top-end that gives the impression of a Flash Gordon spaceship, but maybe it’s best not to expect rocket-like performance from 1950s’ style sci-fi…

After comprehensively rotting away, the wheels were rebuilt with new chrome plated Takasago rims laced onto the original Sachs pressed-steel full width hubs with stainless steel spokes, and wearing new 2.00×17 tyres. The rear hub contains a back-pedal brake operated by the pedal chain, which works a Bendix inside the hub to operate a conventional brake shoe arrangement by a gear driven cam.

Swing arm rear suspension and telescopic front forks are all greased spring units with no damping.

A 6V × 18W Bosch mag set powers the electrics with 15/15W beam/dip headlamp, 3W rear, and an electric horn, which only croaks at low revs and completely fails to work at higher revs, because it’s got a DC horn on an AC system.

A sprung parcel clip snaps down on the rear carrier but is rendered ineffective by the basket fitted on top of it.

There are several reasons why operating the Hobby feels as if it’s going to be little strange … if you rotate the pedals forward, the bike freely pedals forward just like a bicycle, without any engagement to the engine. Then if you turn the pedals backwards it engages the back pedal brake. Because of the hub brake type however, if you reverse the bike, the pedals don’t rotate round backwards as they would on a conventional freewheel, so Hobby is much easier to navigate backwards because reversing pedal rotation can be rather a nuisance when backing traditional cycles.

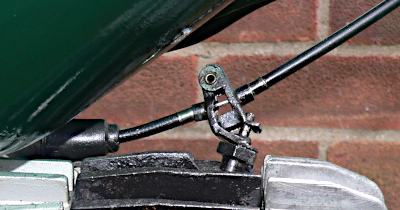

To engage the engine, there’s a large lever on the left handlebar, which is orientated so that it looks like a brake lever—but actually functions as a dual-action decompressor and starter clutch lock, in much the same manner as on a pedal Puch Maxi. Pulling in the lever engages the motor and opens the decompressor, while turning the pedals makes it spin, then release the lever hopefully to get it to start.

Below the right-hand side panel, the petrol tap is operated by turning it back for on and down for off (like, that’s not confusing at all?)

The 12mm Bing carb has a short rod out of the top, which you push down to engage the choke shutter, and a flood button to the float chamber (just like a Puch Maxi) which you can tickle for extra enrichment when it’s really cold. Since it’s a pleasant spring day we resist any urge to agitate the button.

You can start on the stand by kicking the pedal forward while holding the decomp, then release the lever halfway down its stroke. Sometimes a couple of spins might get the motor to fire up, but if this fails and you get bored of trying, then pedal away, intermittently pulling in and releasing the decomp lever, and it usually starts within two or three spins. Run for a little while before opening the throttle to clear the choke, at which point the motor settles to a regular tickover. The exhaust sounds quiet and smooth compared to our previous red example in 2016, since this green bike is fitted with a modern chrome silencer that is appreciably more baffles than the original exhaust had.

We gingerly open the throttle to feel if the choke will clear, which it does quite readily, and with a couple of blips to clear the tubes, it feels as if the bike is ready to go!

The Sachs engine proves responsive to the throttle, delivering a strong and confident increase in revs as it steams against the single-speed automatic clutch to initiate motion, while the muffled silencer tone clears to a smooth drone as the motor comes under load. The pedal ratio feels too low to assist the take-off, while the engine pulls doggedly through the initial phase, then slides into main drive-lock with no hesitation, and pulls onward with a strong and torquey urge as the speedo needle seems to fairly whiz round the dial. 20, 30, 40, (which should be the rated design speed), but carries on well past 50, and still going well as the needle wildly swings on round to over 60! Maybe the 60km/h VDO speedo on this bike isn’t an instrument to be relied upon … good job we have our pacer tracking our steps. It doesn’t take much to get this Hobby off the clock, with the needle pointing back at the rider, and even further round to the 7 o’clock position and back against the stating pin!

It’s fair to say the Sachs engine in our Hobby was revving hard during the run, but we had no idea what the score was. Best on flat 29mph, and best on long light downhill 30mph. The surprise was that this 502/1A motor ran clearly throughout while our previous one suffered from bouts of staccato four-stroking as exhaust gas scavenging seemed to break down as revs increased.

Our previous red Hobby’s best on flat performance achieved only 26mph, which was mostly in four-stroke firing. Ducking into a crouch would barely make any difference since the bike was more held back by its disrupted combustion than by air resistance, and the best downhill run in a crouch paced at 29mph.

The engine on this green example was obviously running cleaner than our earlier red bike, and seems to relish the challenge of any uphill climb, as the engine digs in hard to power up any ascent.

The Sachs 502/1A engine has a contained operating rev range because of its design, and will only work within that envelope. It really wouldn’t be sensible to try and make it do any more than it does in standard trim.

Though dull at tickover, the lights seemed pretty good once the revs got up, and Hobby only has a 6V × 15W AC headlight and 3W tail. Both brakes displayed effective performance, however the rear seemed to need a long arc of back-pedal rotation before it would engage, which made its operation point particularly difficult to judge, and the brake could readily come in hard when it did bite, so the rider needed to be careful.

Another trap the unfamiliar rider can easily fall into is instinctively grabbing the decompressor lever in mistake for a brake, which doesn’t quite achieve the desired stopping result…

It may seem slightly unusual for a bike equipped with a decompressor to also be fitted with a cut-out button to kill the ignition (early pedal versions of the Puch Maxi had a similar arrangement). Most machines started on a decompressor are invariably also stopped on the decompressor, but using the decomp lever on Hobby also engages the clutch, so if the bike is standing on its wheels, it clumsily lurches forward to stop in a stall (not cool). Push the cut-out button and the engine just quietly dies out (much cooler).

If however you happen to have put the bike onto the stand while the motor is still ticking over, then pull in the decompressor lever, it doesn’t stop! The rear wheel starts spinning because the starter clutch also becomes engaged, and pulses of two-stroke smoke loudly vent from the decompressor—but the engine continues running (very silly!) This seems to happen because the decompressor only partially decompresses, because it ports through the sidewall of the cylinder, so there’s still enough compression for the engine to continue running with the valve open.

KTM continues as a successful manufacturer of modern sports and Supermoto motor cycles, but no longer makes mopeds.

The KTM Hobby was a total wreck that came as a freebie, but what’s been the cost to fix it? Rims, spokes, and re-lace £228; tyres, tubes, rim tapes £42; silencer £40; speedo drive £10; blast cycle parts £80; paint £27; headlamp £65; tail lens £10; decompressor £20; switch £15; piston rings £12; capacitor £8; handlebars, pedal arms, and cotter pins £22; pedals £7; grips £4; cables £60; side panels £50 = £700 and a huge amount of work! Would it even fetch that much?