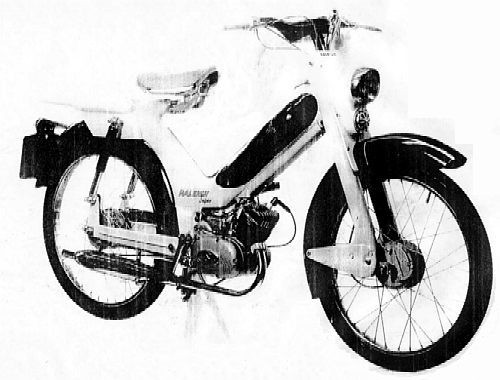

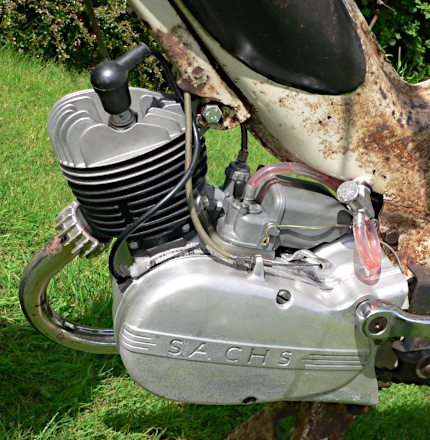

For a long time, we’ve been haunted by this strange monochrome picture of a ghost. A single image of a phantom Raleigh moped… Close study of this spooky image can tell us quite a lot. It’s unquestionably an early period Raleigh-style paint scheme in Charcoal and Pearl Grey and based on a Mk4 Norman Nippy frame. The engine is identifiable as Sachs and easily fitted straight into the frame since Achilles specifically designed it for the Sachs installation in its original format as the Lido. Norman produced its own Super Lido model with a two-speed 2.2BHP Sachs motor, but Norman never produced a production model with the Sachs engine in the Nippy tank-frame (though did offer the combination to ‘special order’).

The headlamp nacelle displays an extended horn binnacle, a feature brought in from a new moulding tool, and not appearing on Norman moped models until the 1961 season.

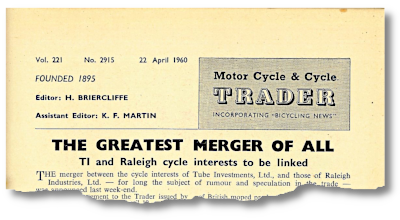

Briefly flashing back for a bit of background to set the stage—on 19th April 1960, the giant Tube Investments Group agreed terms for the takeover of Raleigh Cycles, and Raleigh was subsequently appointed to head up the group re-organisation of all TI companies and products within the British Cycle Corporation, including Norman, Phillips, Hercules, and Sun.

After this the Raleigh Motorised Division at Nottingham would have gained access to British Cycle Corporation products for modelling purposes. How quickly this started taking effect is illustrated by how readily the petrol tank from the Norman Lido appeared to have already been adopted on the new RM4 prototypes announced in November 1960, but it seems the Lido fuel tank wasn’t the only component that Raleigh were looking to adopt…

In October 1960, Raleigh de-listed its Sturmey–Archer powered RM2c moped and announced the start-up of a completely new range of mopeds to be made under licence from the French Motobécane Company.

November 1960: the Raleigh–Motobécane agreement was announced in French press. New RM4 Automatic and RM5 Supermatic models were announced in November 1960 with production scheduled to start in February 1961, and presented in a new two-tone corporate colour scheme of ‘Charcoal and Pearl Grey’ (which was actually more of a light cream, while the Charcoal seemed to be a very close return of the dark grey deployed on the RM1).

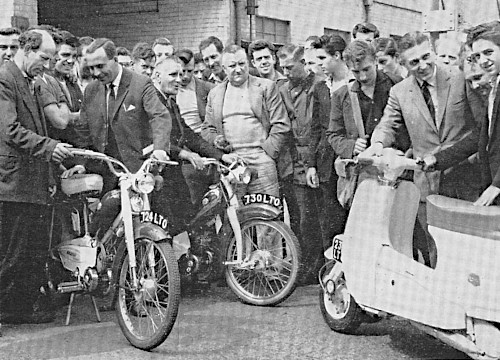

RM4, RM5, & RS1 demonstrators being shown to Raleigh employees

While the new RM4 & RM5 models were officially slated for introduction in February 1961, the Nottingham factory demonstrators however, 417 LTO (RM4), 724 LTO (RM4), and 730 LTO (RM5) were only registered in April or May 1961, and actual deliveries to the trade also seem to have been further delayed since the earliest RM4 registration we’ve recorded was 12th May 1961. The RM5 appears to have fared even worse at getting into production, since the oldest public registered RM5 on our records is dated 21st Aug 1961.

It’s always seemed strange that Raleigh production model numbers had a gap in the early series, RM1, RM2, RM4, RM5, etc, and it has been speculated that ‘The Ghost’ could have been intended to be the RM3, but never went into production, so consequently a gap was left in the model series. That theory could make some sense as the parts already existed to assemble The Ghost before development of the Motobécane based RM4 and RM5 models even began. Since ‘The Ghost prototype’ reflected the same corporate paint scheme as the RM4 and RM5, it would seem fair to conclude that it might have been intended to be the RM3, but that’s only speculation, since there seemed no actual proof to confirm or deny any conjecture…

Dave Elliot’s Raleigh Super

Bombshell 1: after years of wondering about ‘The Ghost’, everything changed on 28th July 2018 when we were contacted by Dave Elliot from Ireland saying ‘I've been given a Raleigh moped to restore and I'm having problems identifying the model (see pics}, the only thing close is the RM3 prototype but this was never put into production, it’s been suggested that it’s a Norman, but only has one owner from new and the decals look original’. Frame E12396 with the Irish registration issued in 1961, Sachs-50 engine number: 3458217 x 2-2.2bhp, 2-speed, 47cc, year 1960.

The frame number is clearly an extension of the Norman Mk3/Mk4 series, and the Sachs engine from the Norman Super Lido series, but that’s a period Raleigh paint scheme!

Liam Hackett’s Raleigh Super

Then remarkably, and just two days later on 30th July 2018 we were contacted by Liam Hackett from Ireland, enquiring after a replacement headlamp nacelle for a Raleigh Moped ‘Mk4’, with a Sachs engine! Following a few e-mail exchanges we confirmed frame serial E12881, Sachs 50 engine number: 3459256, 2.2bhp, 2-speed, 47cc, year 1960. This bike was also accompanied by the original Irish registration document dated 31/09/1961. We also received some pictures. This bike had been fitted with a 19-inch Puch VS50 rear wheel and toolboxes, and a Suzuki dual seat.

What these two bikes demonstrate is that the picture of ‘The Ghost’ was not just a prototype, but an actual production machine which was uniquely sold into Eire. Not only that, but these models were already made, delivered to Eire, and being sold across Southern Ireland before Norman was closed on 30th August 1961.

Unlikely as this situation may seem, were they built up and painted in the Charcoal grey and Pearl grey (cream) Raleigh livery as per the new RM4/RM5 models, and finished by Norman at Ashford in Kent, or by Raleigh at Nottingham who would have needed access to the Norman cycle components?

However it was done, that’s undeniably a period Raleigh paint scheme!

The frame numbers are clearly an extension of the Norman Mk3/Mk4 series, and the Sachs engines from the Norman Super Lido series. The silencer is Villiers 3K, and fits onto the Sachs exhaust pipe, exactly the same formula as the Norman Super Lido as clearly illustrated in Norman literature, and Norman also operated as a Sachs spare parts and service dealership from October 1958.

We had a vague plan to go over to Southern Ireland to check these bikes out ourselves, but until one or both these machines might be fixed up to running order again there hardly seemed much point.

On 29th March 2020, we received a third contact from Tom Cahill in Ireland about another derelict Raleigh–Sachs, which was missing its complete engine top-end and carburettor. Following some protracted negotiations we finally agreed terms to buy the bike, then arranged shipment back to England in June 2021, by which point there was no available workshop time to begin rebuilding the bike until October 2023, then completed for UK registration in March 2024.

While the bike has been mechanically restored, its original finish has been retained, because if it were repainted, nobody would believe it…

Frame serial E16855, Sachs engine type 50M AB 10068 number 8813501 2-speed, 47cc, year 1962, and originally registered SZE 12 from Dublin, Ireland in April 1964.

Bombshell 2: this confirms that Raleigh was still selling these ‘Super’ models until 1964, so they had clearly remained on sale in Eire over four years, though that wouldn’t necessarily mean that they were still being built after four years, because they could have simply been clearing old stock since sales volumes in Southern Ireland weren’t exactly significant numbers at this time due to an ongoing sales recession.

The most stunning aspect about this third machine compared to the previous two examples, is it has a 1962 manufactured Sachs engine! So what’s the significance of this?

Well … the first two examples both had 1960 dated Sachs engines, which were simply taken from Norman stock, but Norman closed on 30th August 1961.

The 1962 engine in our third machine couldn’t have been taken from Norman’s stock, so must have been delivered from Sachs direct to Nottingham! This leads to the conclusion that Raleigh must have exhausted the Norman/Sachs engine stocks, and needed more motors to fit already completed frames. We can’t tell whether these were some outstanding Norman orders with Sachs under contractual obligation (You have to pay for these contract engines anyway, whether you take them or not), or whether a top-up batch was ordered from Sachs by Raleigh.

It was most probably the latter, and following the closure of Norman, remaining assets from Ashford were cleared back to Nottingham. At which point Glass's Index simply listed the Norman Nippy Mk3 and Super Lido models in 1961, but not in 1962, which most probably represented existing trade stock clearing. The Norman Nippy Mk4 with Villiers 3K/1 engine remained listed by Glass's until May 1962 and was indicated discontinued at frame number E15527 (presumably built out in Nottingham).

Unlisted’ Villiers-engined Norman Lido

A small number of 'unlisted' Villiers 3K engined Norman Lidos re-appeared in late 1961/early 1962 as an unofficial model’, seemingly to build out the remaining Villiers engines. Gone were all the stylish engine covers of the original model. These final Lidos wearing only a simple chain guard and plain orange paint seemed little more than the basic Nippy Mk4 with a fitted petrol tank.

A number of characteristic features unquestionably confirm these unlisted Lidos as genuine late production machines, and certainly unconnected with the original 1959 batch. The new headlamp nacelle, only introduced in 1961, features the extended horn binnacle, and a plastic badge on the left hand mag cover clearly indicates the motor as a 3K/1 version, which Villiers only introduced in 1961.

Since the Sachs Super Lido so quickly disappeared in 1961, and the Lido frame was subsequently built out with Villiers engines, maybe Raleigh were trying to save all the remaining Sachs engines for the Irish ‘Super’ models?

Looking deeper into fine details of our Raleigh ‘Super’, we noted the 19-inch Dunlop moped tyres were marked ‘Made in the Republic of Ireland’, whereas the same 19-inch Dunlop tyres fitted on British market mopeds were always marked ‘Made in Great Britain’, and the same 19-inch Dunlop tyres fitted on Phillips mopeds in New Zealand were also marked ‘Made in New Zealand’ and moulded at the Dunlop plant at Upper Hutt near Wellington, suggesting that many export bikes were being sent out in semi-knockdown form for fitting with tyres in the markets they were sent to. The Dunlop Company originated in Ireland, with a production facility at Dublin and, when we removed the tyres to overhaul the wheels, the Dunlop inner tubes were also marked ‘Made in The Republic of Ireland’.

Which leads to another question: where was the Raleigh ‘Super’ built?

For the first season in 1961, the Norman factory was still functional up to the 30th August, and all the parts were there, so these ‘could’ have been made in Ashford, but would Norman have painted them in the new Raleigh charcoal and pearl grey finish, and applied the Raleigh decals?

Examination of the ‘Raleigh Super’ decals on the lower part of the frame above the engine mounting confirms our suspicion that these were actually ‘Raleigh Supermatic’ side panel transfers with the ‘matic’ cut off.

Did Norman send all the parts to Nottingham for Raleigh to finish and assemble, which must have been in the very early part of 1961 for the bikes to be finished and delivered to Eire in time for the sales season? Then Raleigh continued building from transferred parts after Norman closed?

Or did Raleigh finish the parts, and send them in knockdown form for assembly at the Raleigh factory in Ireland? Ahhh! Maybe you didn’t know about Raleigh Ireland?

The Raleigh factory was situated in Hanover Quay Dublin, and from Thom’s Dublin Street directory, Raleigh was first listed at No.6 Hanover Quay in 1939. In 1943, they moved to Nos 8-11, where a full range of Raleigh cycles were manufactured at this Dublin facility in the post war era.

The cycle head badges changed in the late 1960s, possibly after the passing of the Trade Descriptions Act in the UK. Dublin-made machines no longer had ‘Nottingham England’ on the Heron or Triumph head badge, the panel being left blank instead.

Being an early factory, built and used before safety regulations came into practice, the wooden floor soaked up all the oil, grease and other flammable lubricants over the years, so that when a fire started in 1976, the whole factory burned to the ground, and led to the biggest insurance payout in Irish history at the time. Unfortunately all the records stored in the factory were lost.

After the fire, Raleigh stayed in Ireland, but only as a distributor, not a cycle manufacturer. They built another factory, but quickly downscaled to suit their distribution network.

There’s a lot of questions arising about ‘The Ghost’, but finding answers isn’t so easy … so lets look at the bike.

It’s basically a Norman Nippy Mk4 with a Sachs engine, which offered a comparable rating to the Mk4’s Villiers 3K. Both were two-speed hand change, the Villiers 3K had 40mm bore × 39.7mm stroke with 7:1 compression ratio for 2bhp@5,000rpm, compared to the Sachs’s 38mm bore × 42mm stroke with 7.3:1 compression ratio for 2.2bhp@6,300rpm, while both motors were fitted with the same size 12mm carburettors by Villiers or from Bing, and both models had the same Villiers silencer!

The Norman Nippy Mk4 with its heavy Villiers 3k engine weighed in at 119 lb, meanwhile the Norman Super Lido with lighter Sachs engine, but heavier separate fuel tank and heavy steel engine covers weighed 116 lbs.

For obvious reasons, nobody has ever formally weighed a ‘Super’, with the lighter in-frame fuel tank, lighter Sachs engine, and no engine shields… So 21.5kg front + 28.5kg rear = 50kg = 110 lbs, and that’s a wet weight, with engine oil and fuel. ‘Super’ is 9lbs lighter than the Mk4, which we always considered a heavy and slow bike.

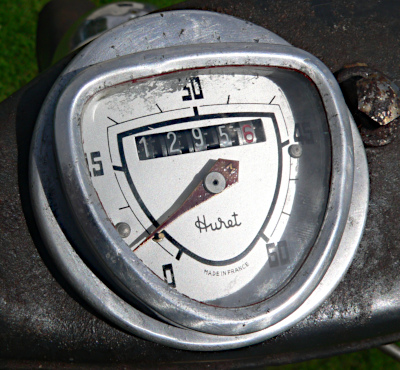

With a mileage of less than 1,300 on the odometer there’s very little wear to take into account, and the bike looks to be standing tall on its stand with a 3-inch ground clearance to the rear wheel. There’s a triangular 0-60 Huret speedometer mounted in a round-formed aluminium plate, which we’ve seen before on one of the later ‘unofficial’ Villiers Lidos.

Handlebar controls are Amal, which means it uses the same cables as the Super Lido, while the seat is the archaic Wrights S.65/3 ‘tension coil sprung’ single saddle, which in previous road tests has historically achieved a deserved reputation in the discomfort department awards. Because of the forward facing mounting on the frame, the saddle height is fixed and cannot be adjusted.

Behind the saddle is the lockable lid to a toolbox, built into the frame’s one-piece rear carrier, and remarkably we even have the keys!

The Ewarts plunger fuel tap is located at the bottom left of the frame, pull on for main tank, then turn the plunger clockwise and pull again for reserve. There is no choke fitted to the Bing 12mm carburettor, so the only enrichment method is a flood button on the top of the float chamber. Since it’s a cold day, we flood the carb, then the easiest way to get a pedal into position for starting is to pull in the decompressor trigger under the throttle control and turn either pedal into position to kick down. Check that neutral is selected on the gear change, kick down and the motor fires up first time, then peters out after a few seconds, rinse and repeat a couple more times, at which it gets the message, so we run a while to warm.

Engage the clutch and twist the grip forwards to locate first then feed out the lever while increasing the revs. The original top-end was missing from the engine when it came, so the motor was rebuilt with a twin reed-valve cylinder, because we thought the Sachs reed-valve would be interesting to try out, and we just happened to have one, whereas we didn’t have an original type 2 2.2bhp piston ported cylinder.

While common on the continent, the Sachs twin-reed cylinder wasn’t generally sold on the UK market.

Reed Valves

English engineer Joseph Day 1855–1946 came up with a design that would not infringe the patents of Nicolaus Otto’s four-stroke engine. Day eventually called his concept a ‘Valveless Two-Stroke Engine’, though there was at least one simple check valve in the inlet port communicating directly with the crankcase, where you would probably find a reed valve on a modern two stroke.

His patent No.6,410 of 1891/2 covered design variants with a piston controlled transfer port or an additional check valve in the crown of the piston through which the combustible mixture could pass from the crankcase to the cylinder.

While Yamaha is acknowledged as the first Japanese manufacturer to introduce reed valves as standard equipment on its motor cycles in 1974, the Sachs moped engine obviously pre-dates that, and is the earliest production reed-valve arrangement we’ve seen fitted to any moped. A 1956-57 Triumph 200cc twin-cylinder two-stroke prototype motor cycle featuring reed valve induction may pre-date the Sachs. The 99cc Villiers 11F crankcase induction motor is another example of an obscure early reed-valve, seemingly produced in only small numbers for Junior Kart racing in Class-1 and Class-1 Super in the late 1960s.

Releasing the clutch at low revs doesn’t result in the expected stall which would probably be anticipated from a piston ported motor. The ‘Super’ will crawl along in first at barely walking pace, though the reed-valve feels quite gentle in providing torque to pull the revs up on throttle alone, so either slip the clutch to increase the revs, or pedal assist to increase speed (though the Nippy frame isn’t very efficient to pedal because the high pedal shaft position makes effective pedalling somewhat awkward). The Sachs reed-valve doesn’t achieve the same degree of effective torque that appreciably larger volume modern reed-valves deliver, which is probably due to the 2 × 11mm diameter limited port sizes of the Sachs reed plate. The result is that the Sachs reed delivers a much more ‘softened’ torque throughout the rev range.

The 60mph Huret triangular speedo indicates up to a max in first of 20mph, then clutch for cogging up to second, twist back the grip, so the clutch lever is now at a level height with the front brake lever. We quickly become aware of the seemingly clonky suspension, both front and rear, but we’re unsure as to why this may be, since the low 1,300 mileage on this machine indicates no appreciable wear, and it’s recently serviced, so the only thing we can imagine may be responsible for the noise might be if the rubber rebound stops have perished, but to check this would required the front suspension link assemblies stripping out for access.

Sachs reed valve

Pressing on, the Sachs engine settles down to maintain a comfortable cruising speed indicating 28–30mph on flat, which paces at 26–28mph. As the engine warms up a maximum indicated 30–32 on flat paces at 28–30mph, and best downhill indicated 34–35mph, and paced off at 32–33mph. This Huret speedo appears to indicate 2mph fast.

These period Sachs 50 engines all have the same basic engine specification of 38mm bore × 42mm stroke giving 47cc, but there are a lot of variations on the theme due to different cylinder versions with alternative porting options, different compression ratios from 6:1 up to 9:1, and alternative carburettor options from 9mm through 12mm, and 17mm. Our engine has a compression ratio of 7.3:1, and the only reference we can find on the twin-reed motor suggests ‘up to 2.6bhp’, which would presumably be with the 12mm carb fitted. Because these twin-reed engines were mainly sold into continental markets, we presume they would have been made to comply with a 50km/h specification (31mph), or 30km/h with a 9mm carb (19mph).

The back pedal rear brake proved the stronger of the two, mainly due to the extra power that can be applied by foot action, while the front brake also proved capable too, though strong lever application tended to cause the front to lift on the leading-link front suspension, so probably requires judicious use under potentially slippery conditions. Handling was generally good on smooth roads, but unpleasantly clonky over bumpy surfaces. All the Miller lights worked effectively, and were quite bright for such an early machine, the Miller horn even gave a good wake-up buzz, and the cut-out button stopped the bike without the twitter associated with using a decompressor to kill the engine.

The exhaust tone was a pleasant subdued burble, and easy to live with.

Having got so far, and established that ‘The Ghost’ existed as a real production machine, we need to understand why? And why are they found only in Southern Ireland?

This would need further research to fill in the gaps, but when everything about Raleigh mopeds is pretty much already known … then it’s necessary to go to an untapped resource to find something that may not have been discovered already … Nottingham Archives, for Raleigh Industries Company Records, which can be filtered down to just 3,700 files!

Eire, Éire, or Ireland?

The word ‘Ireland’ doesn’t appear anywhere in the Raleigh–Motobécane agreement; it’s always referred to as ‘Eire’. The Irish Free State was formed in 1922 and, in a new constitution adopted in 1937 became officially known as Éire (in Gaelic) or Ireland (in English). The UK Government, however, refused to call it Ireland and insisted on calling it Eire (without the accent on the first letter). Therefore, in any legal document like the Raleigh–Motobécane agreement, it had to be called Eire. In Gaelic the accent is important, without it the word means a burden; however, with most legal documents being typewritten, leaving the accent off was a practical measure: English typewriters didn’t do accents.

We started with a targeted search and reprographics order, on details of the Raleigh/Motobécane contracts for analysis.

In the first Principal Agreement of the Raleigh/Motobécane Contract dated 5th October 1960, we find:

2b.) In particular, RALEIGH shall be permitted to use and embody the NORMAN frame in Mobylettes which it will manufacture or assemble, provided that the frame is first submitted to MOTOBECANE for its approval and subsequent agreement.

This appears to be the first confirmation that something was going to be required to cover a licensing gap for the Eire market, because the licensing agreement with Motobécane only applied to nations belonging to the British Commonwealth. This meant that Raleigh wouldn’t be able to sell its Motobécane based mopeds in Southern Ireland—even though they were already a well-established brand there. This would represent a future issue for Raleigh, for which they needed a plan, and a realisation that the Norman Mk3/Mk4 frame was being proposed as a prospect for installing a Motobécane engine and presumably primary transmission set to enable the drive. This would also require a pedal drive set on the right-hand side and freewheel mounting on the British Hub Co. rear hub (as per the Hercules Corvette).

The commercial people dealing with the contract may not have anticipated the technical department’s response to this proposal.

4a.) RALEIGH will have the right to apply any suitable name, description, or trade mark to Mobylettes manufactured or assembled by itself or purchased from MOTOBECANE.

Which covered the forthcoming Phillips Panda Mk3/Gadabout Mk4 and Norman Nippy Mk5/Lido Mk3 branded models, so these were already planned in at this time.

Supplemental Agreement dated 11th April 1961, in section 12.) re ‘RALEIGH's existing stocks of mopeds’:

In view of a trade recession now apparent at this date, it is acknowledged RALEIGH may have difficulty in selling by 31st December 1961 … MOTOBECANE therefore concedes that Raleigh shall have the right to ask for an extension beyond 31st December 1961, but it is understood that such extension shall be only for the purpose of using up existing stocks and that it will be limited, except by new agreement, to 31st December 1962.

This seems to represent an acceptance that remaining stocks of Raleigh RM2 and Norman/Sachs models may not be sold by end 1961 due to a trade recession, and formally allowing the possibility of an extension to the end of 1962.

Supplemental Agreement dated 3rd July 1961:

Considering MOTOBECANE'S engagement in Eire and the existing position of RALEIGH in that country, the following has been agreed after much consultation.

1.) Till 31st October, 1961, Eire will become included amongst the Countries mentioned in clause 1(c) 5 of the Principal Agreement between the parties being the Countries in which RALEIGH can sell the vehicles therein mentioned.

2.) From 1st November, 1961, Eire will be included among the Countries of Appendix II, i.e. Countries in which RALEIGH has the right to sell Mobylettes and only Mobylettes in co-existence with MOTOBECANE.

3.) Both parties want to make it clear that the rights granted to RALEIGH by the preceding paragraph 2 cover the import of Mobylettes into Eire in the C.K.D. condition, and the right to carry out reassembling in Eire.

(Dated 29th September 1961).

Meaning that from 1st November 1961, Raleigh could now sell RM4 and RM5 models into the Eire market, and while it may have appeared that all the Norman/Sachs ‘interim’ models might have been sold, we already know they weren’t. Our featured machine with its 1962 engine didn’t even exist at this point, and wasn’t actually sold till 1964. Perhaps Raleigh thought the small numbers it made weren’t of significant concern? Passage 3.) Also indicates that mopeds were shipped to Eire in knockdown form for assembly at the Raleigh Dublin plant, as confirmed by the fitment of Dunlop R.I. moulded tyres and tubes.

Having previously had only a low quality photocopy of the right-hand side picture of ‘The Ghost’, we managed to track down and secure high-res scans of the Raleigh black& white photographs of both sides of the ‘Super’, and a right-hand side artistic illustration! You’ll note this shows no spokes, so what might the illustration have been used for? Initially maybe to demonstrate the planned paint scheme before the first model was built? Illustrative use in manuals, promotional advertising, since newspapers, magazines and leaflets that don’t need to show high-res images.

Examination of the Raleigh black & white photographs and the illustration, are notably an identical scheme to the ‘first batch’ 1961 bikes, having Typ Sachs 50 2 – 2.2ps 1960 dated engines, and specifically have a ‘pearl grey’ painted rear swing-arm, Lycett rubber covered saddles, and the same ‘flat’ British Hub Co. hubs with dished rear sprocket as used all the Norman models.

The ‘second batch’ machines (as E16855, Sachs engine type 50M AB) differ in that the swing-arm is painted charcoal, it’s fitted with a Lycett tension sprung saddle, and has ‘domed’ B H Co hubs with a flat rear sprocket.

Since time is now running out to our editorial deadline, and we’re still struggling for information to solve this puzzle, we’re just going to have to go to Nottingham and search the Raleigh Archives ourselves.

Working through the entire archive list on-line, we narrow down to the most likely references, and pre-order our first block of four files starting at 9am on a Tuesday morning, then working through and maintaining the rate of four file blocks per hour up till late night closing at 7pm, then a four-hour drive back…

All this, and nothing on our Eire ‘Ghost’ … though we did find an untitled file negative, seemingly of an unknown Sturmey–Archer engined MkIII prototype.

Ref: DDRN6/28/1/4/404

What we can tell from a subsequently printed photograph from this deteriorating 64-year-old negative: It has telescopic forks, with the same hubs as the RM1 & 2, but using 19/23-inch wheels, which would reduce the overall drive ratio by 11.5%.

While the motor seems to have the same cylinder head as the RM1 & 2, there seems to be a different engine below. The cylinder has the exhaust port at the front of the cylinder, and the pipe fitted by a screw-in gland nut. It looks to have a conventional two-journal bearing crankcase, and ‘something’ on the far side of the motor, which you wouldn’t expect to see on the overhung crank engine. The RM1 & 2 had an Amal 385/1 carburettor on the left, but this carb seems to be something different?

XTO 923 is a Nottingham registration ... issued around September/October 1956. So they must have re-used a registration number they already had, which was presumably taken out as a Raleigh R&D registration to road test development prototypes. However, it has a 1960 tax disc, which was still in the era when they all expired on 31st December, so the photo was taken in 1960.

This prototype would have been stone dead on the day the Motobécane contract was signed on 5th October 1960, though this project was most probably struck off before that point.

When IceniCAM interviewed former Raleigh (Southeast Region) Sales Manager David Denny in September 2009, he told us the RM3 was originally an engine development project run by a former Standard Vanguard engineer. Though utilising the existing Sturmey–Archer cylinder barrel, piston, and Lucas mag-set, this engine had dispensed with the earlier overhung crank arrangement and was based on a motor with journals each side, then driving through a ‘Standard’ powder operated automatic clutch! Difficulties in the clutch operation reportedly led to abandonment of this project.

Powder Clutches

Peugeot introduced a new BB series of Peugeot mopeds at the Paris Salon in 1957, which was launched by the original BB1 model with a powder clutch. Powder clutches were a fashionable gimmick of the day that a number of manufacturers (including Raleigh) dabbled with at the time, but none of the various interpretations of the idea developed any longevity, which serves to underline how ineffective the novelty was in actual operation. The real winning transmission system for small capacity motors soon proved to be the simple and automatic mechanical centrifugal clutch, and Peugeot quickly switched over to the more logical solution.

The interview notes record that when asked about the ‘Ghost’ picture, he knew nothing at all about the Raleigh ‘Super’ with its Sachs engine.

Rather than finding confirmation as to whether ‘The Ghost’ may actually be the ‘lost’ RM3, the situation has seemingly become just more confused with the startling discovery of the prototype Sturmey–Archer Mk.3 picture. Both appear at different ends of the most likely period between RM2 in early 1960 and announcement of RM4 & RM5 in November 1960, and both could be candidates on their own very different merits. The Sturmey–Archer Mk.3 was a significant R&D prototype featuring several progressive details, including an extensively revised engine, though obviously never approached any prospect of production.

Though produced purely as a ‘stop-gap’ machine in Eire for 1961, the ‘Super’ clearly made planned production in two distinct manufactured batches, and was built in numbers that meant that stocks weren’t sold out in its first year, continuing into 1964 when our own example became registered.

Published records from Motor Cycle & Cycle Trader magazines of Raleigh sales in Eire indicate 49-mopeds registered up to September 1961 (December edition), and a further 72 for 1962 (April ’63 edition). Eire sales weren’t big numbers, as the market was reportedly restrained by an ongoing trade recession, though Raleigh were still the highest British manufacturer in unit sales, pushing BSA into second place.

As per the Supplemental Agreement of 3rd July 1961, from 1st November 1961 Raleigh could start selling RM4 and RM5 models into Ireland alongside uncleared stocks of earlier models, which would have contributed to extending the time taken to clear the outstanding ‘Supers’.

It’s likely that the majority of Irish sales in 1961 were ‘Supers’, and represented a significant proportion of the sales in 1962, then steadily reducing into 1963 and ’64. Obviously we have no idea how many ‘Supers’ were sold but our best guess would probably be between 100 & 200.

It’s interesting that same style of ‘no-spokes’ artistic illustrations of all Raleigh mopeds from RM1 to RM12 drawn for manual illustrations, leaflet applications and commercial adverts was also drawn for the ‘Super’, which was only done for production machines. Raleigh wouldn’t have done that without producing manuals, leaflets and commercial adverts, any of which would probably confirm what they actually called the machine, but such literature on the ‘Super’ can’t be found at all in the Raleigh Archives at Nottingham, and might only seem likely to be found in Southern Ireland.

While working through Nottingham Archives files, and having worked in industrial design for a number of years it became apparent that the RM model prefixes were merely numbers issued to new projects by the Raleigh Research & Design department, and upon reaching production, models tended to be given additional titles:- RM1 Moped, RM2 Moped, RM3? RM4 Automatic, RM5 Supermatic, RM6 Runabout, RM7 Wisp, RM8 Automatic MkII, RM9 Ultramatic, RM9+1 Ultramatic (instead of RM10?), RM11 Super Tourist, RM12 Super 50.

It seems as if bikes that specifically didn’t achieve production, failed to be included in the Raleigh list of models, which is indicated by the two numbers that don’t appear because they never got beyond the R&D phase.

The ‘Ghost’ was a brief stop-gap machine resulting from a contractual glitch, though it wasn’t the RM3.

It managed to remain undiscovered in the Republic of Ireland for 60 years, and is without doubt, the rarest production Raleigh moped, but can only really be known as the Eire ‘Raleigh Super’.

All the pieces fitted together as our 15-year old interview notes with David Denny tied up with the ‘different’ Sturmey–Archer engine in the untitled negative of the Sturmey–Archer Mk.3 prototype, which never got beyond R&D, and is very probably the only known surviving image of the RM3.

The ‘other’ gap in the Raleigh model series positively confirms that only R&D numbers of machines achieving production were included in the models list … though that’s another story for another day … but a story that is underway…