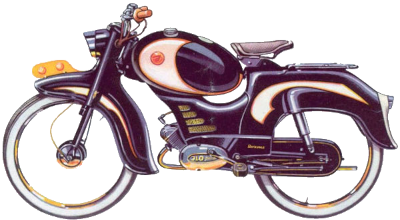

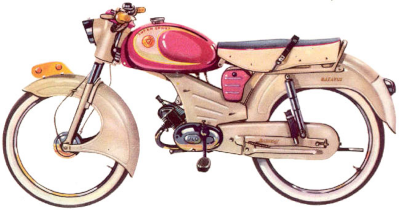

From cyclemotor frames fitted with Mosquito engines in 1950, the Batavus Company progressed through Bilonet step-through-frame commuter mopeds with Ilo engines in 1953 to its first sports moped as the Bilonet G50 Sport in 1957, from which it began a period of producing lots of sports mopeds, at a time when such models were particularly popular.

1959 Batavus CombiSport

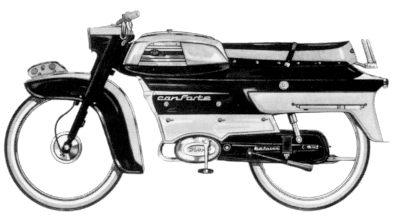

1963 Batavus Conforte

1959 Batavus Super Sport

Subsequent sports model names include Super-Sport, Conforte, Combi-Sport, Whippet, Husky, and Tramp, up to 1968. While the current production sports models looked very smart with partially chrome plated tank panels, their two-speed and three-speed hand-changed gears were beginning to be a little dated. Batavus had also been fitting Ilo engines since the early 1950s, but this manufacturer stopped supplying moped motors in 1968, and Batavus had to discontinue existing models once it ran out of motor blocks to fit each respective type, having to start producing a completely new range of commuter machines using Anker–Laura and Sachs engines.

Magneet was another Dutch moped manufacturer, also starting from similar cyclemotor origins in 1951, through step-through-frame mopeds, sports mopeds, and introducing some smart new sports moped models in 1968 as their Magneet Thunderbird 20 (Sachs fan-cooled) & E8 (Sachs air-cooled) models.

Batavus took over the Magneet factory in 1969 and, with it, adopted the Thunderbird sports models, which were re-launched under the Batavus brand as the TS49, initially with Sachs air-cooled two-speed and three-speed gears, then later with a four-speed foot-change Sachs engine; and the TS50 with a fan-cooled Tomos 4L engine.

By this time the moped market had changed dramatically, with an enormous rise in basic commuter mopeds compared to falling demand for sports style models, so Batavus brochures of the 1970s devoted most of their content to the shopping or ‘lady’s’ mopeds, while the TS models were relegated to the back pages (where only the letter S suggested it might be thought of as a sport model). The accompanying description emphasised the ‘motor cycle’ qualities of construction, sturdy brakes and the spacious pillion seat. (Batavus also supplied its ‘heavy mopeds’ to the German market as 50cc Motorräder (motor cycles).

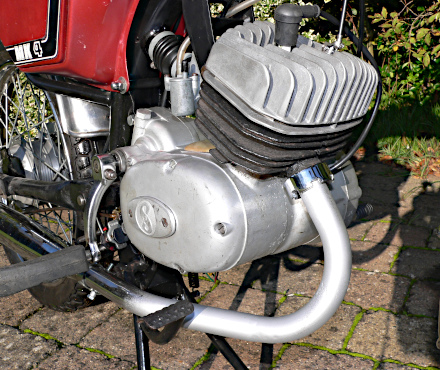

In 1974 the TS models had disappeared from the Batavus brochure, to be replaced by the Mk2, Mk4, and Mk4S as the flagships of the new fleet. The Mk2 had a hand-change two-speed Sachs engine, with a large headlamp shell containing the speedometer. The Mk4 was a similar version to the Mk2 with same headlamp containing the speedo, but fitted with a four-speed foot-change Sachs engine. The Mk4S also used the foot-change four-speed Sachs engine, but carried a plain headlamp shell with a separate speedo and a 6V AC electronic rev-counter fitted on a bracket above the headlamp, and also available with an optional indicator set.

In 1976 this trio was still available, and the Mk4S gained two more bolt-on tubes from the steering head to the bottom of the engine, so giving the (fake) appearance of a double cradle frame. The colour schemes had also changed over the years.

Our Batavus is a Dutch market model Mk4S with separate headlamp, speedo and rev-counter assembly, dated 1976, but produced before they added the cosmetic bolt-on frame tubes. It came with the remains of the indicator set, and complete with the yellow front mudguard plate, confirming it was built to the 50km/h spec, and fitted with a 12mm Bing 1/12/228 carb, 13T front sprocket & 30T rear sprocket.

Mopeds (Bromfiets) in the Netherlands were included under specific vehicle regulations, and Dutch mopeds at this time were not registered as such, only being marked by rear plates for insurance. A Dutch moped having a maximum construction speed of 45–50km/h (28–31mph), was identified by a yellow plate on the front mudguard and, in 1975, it became mandatory to wear a helmet on these mopeds.

There were objections to the helmet law, particularly in rural areas where women still wore the traditional Dutch headdress, so a new Snorfiets category of moped (identified by an orange plate on the front mudguard) was introduced. This was a performance-limited class of moped restricted to 25–30km/h (16–19mph), for which wearing a crash helmet was optional, not mandatory requirement. The term ‘Snorfiets’ is a euphemism meaning ‘purring bicycle’, though machines are sometimes referred to as ‘Mustache’ in the Netherlands, since ‘Snor’ also translates to moustache in English. The maximum speed that a Mustache or Snorfiets moped may reach is 5km/h above the construction speed. Therefore, a bromfiets may run up to a maximum of 50km/h, and a snorfiets to 30km/h, but the rider would be obliged to keep to the specified maximum speeds of 45 and 25km/h respectively.

There were so many specifications for the 50/4 Sachs motors that it can be difficult to identify the actual ratings to respective bike/engine models. For example:

50/4LKH rated 4.3bhp @ 7.200rpm

50/4LKS rated 1bhp @ 3,500rpm with 9.2mm Bing 1/8.5/14

50/4LF NL (Dutch market) rated 1.8bhp @ 4.200rpm

50/4MLFA NL (Dutch market) rated 1.8bhp @ 4.200rpm with 12mm Bing 1/12/168 (60 main jet)

50/4MLFB rated 2.6bhp @ 5,000rpm with 12mm Bing 1/12/168 (60 main jet)

50/4MLKAX rated 2.8bhp @ 5,800rpm with Bing 1/12/167 (64 main jet).

50/4 DFX rated 3bhp @ 6,000rpm with Bing 1/18/34 carb (UK market Mk4S sold Aug 1974 – Jul 1977).

Maybe this gives some impression of the complication involved here.

The large fuel tank capacity is given as 11 litres (2.4 gallons), and thhe weight quoted at 7.6kg (160lb).

While the bike is very stable on the stand (with the front wheel showing about an inch clearance), it requires a surprising amount of lifting to get the bike off the stand. At least having a firmly fitted rear carrier helps by givin something to hold the back of the bike with.

The petrol tap is located at the bottom left of the tank with the lever indicating C for close (pointing back), down for on, and R for reserve (pointing forward). There’s a flood button on the carb float chamber top, and a choke shutter operating rod sticking out through the air slide top, which will obviously lift off in the normal manner when the throttle is opened.

The motor, however, doesn’t seem to need any enrichment, since you just raise either side of the dangly pedal set, pull in the decompressor lever under the left-hand bar set, press down on the pedal to get the motor spinning, release the decompressor lever, and the motor starts first time. Easy!

We warm the motor for a few minutes while we wait for our pacer; the VDO magnetic speedo is marked up to 100km/h, so we want to check that against our pacer’s mph readings. The clutch feels light enough in action, though the long motor cycle type lever probably helps. The left-hand gear lever shift pattern is one-down & three-up, though first gear seems a bit hard to locate from neutral. When first is engaged the gear runs out of ratio by 15km/h (10mph), so it’s no issue to just pull off in second. The motor pulls capably enough as you work up through the gears, but doesn’t pull as hard as you’d expect as the revs increase. The electronic 6V AC rev-counter is marked up to 10,000rpm, but there’s not much above 4,000rpm available in the lower gears and it pulls less than that in top gear giving a best on flat speedo indication of 50–51km/h (paced at 30mph), and in light downhill sections best indication 53–54km/h (paced at 31–32mph). Maximum revs at these speeds in fourth were around 3,750rpm, so the motor obviously had plenty more unreleased potential in it—but not with its restrictive Dutch market 12mm carb.

One good thing about these performance restricted models: at least you know they’re never going to be thrashed to death.

The 2.50 × 17 tyres feel well planted on the road, while the cast alloy and fully machined 105mm Leleu brake hubs look a good quality finish, and prove effective stoppers.

The Mk4S is a solidly constructed moped with the physical proportions of a light motor cycle, so a very capable mount for larger and taller riders. The suspension rides well at both ends, and the sound frame construction far out-handles the restricted performance of this Dutch market model.

The headlight was bright, and the tail lamp unit included a brake light powered from a separate boost coil, so the lights don’t go out when the rear brake pedal is pressed.

The exhaust tone was remarkably quiet, though it has a new pattern chrome silencer … we don’t expect the original would have been so effectively baffled.

Without the performance limitations required for the Dutch home market, the UK market Mk4S version was fitted with a Bing 1/18/34 18mm carburettor and quoted at 3bhp @ 6,000rpm for 46mph, equipped with the fitted indicator set as standard, and sold from August 1974 (£275) to July 1977 (£335).

In comparison, the Yamaha FS1-E was priced at £280 in April 1977, and quoted at 4.8bhp @ 7,000rpm for 48mph, so the Mk4S cost 20% more.

Since 1974, when the Mk4 was launched at ƒ1,506 (Dutch Guilders), inflation had increased the price up to ƒ1,798 by 1978, by which time the Mk2 and Mk4S had already been discontinued.

Batavus was also selling its mopeds in Belgium, Luxembourg, and on to German mail order companies, which were offered there as Starflite Motorrad (motor cycle) equipped with kick-start and fixed footrests. Popular commuter Batavus mopeds also experienced price inflation on the Dutch market, which became an issue affecting home market sales, but the main factor was the moped market slowly dwindling away against the emerging popularity of the 50cc CVT scooter.

Batavus Starglo and Pronto moped models continued to be listed in the UK until 1984, when Batavus finally ended moped production and returned to concentrate on its core business of bicycles. Two years later, the Batavus group folded.

Subsequently, a revival was made under the new ownership of Atag, who returned the Batavus name, though only as a bicycle brand, and primarily in its home Dutch market.