Chalk

Johann Puch was born in 1862, and worked from 1889 as an agent for British Humber & Co Ltd, the manufacturer of bicycles, motor cycles and cars. In 1890 he founded his first company, Johann Puch & Co, as the manufacturer of Styria safety bicycles, employing 34 workers in a small workshop in Graz. By 1895, Puch already employed more than 300 workers producing about 6,000 bikes a year, then Josef Fischer winning the first Paris–Roubaix road race event in 1896 further popularised Styria cycles, which were then exported to England and France.

In 1897 Johann left his first company following a dispute with his business partners and, in 1899, founded the First Styrian Bicycle Factory AG (Erste Steiermärkische Fahrradfabrik AG) in the Puntingam district to the south of Graz. Puch’s second company also became successful because of its reputation for quality and innovative ideas, and it rapidly expanded into producing motor cycles. The manufacture of engines started in 1901, and was followed by the building of cars in 1904. In 1906 the production of the two-cylinder Puch Voiturette (motorised tricycles) began, and in 1909 a Puch car broke the world speed record with 130.4km/h (81mph). In 1910, Puch is credited with producing sedans for members of the Habsburg Imperial family.

In 1912, at the age of 50, Johann Puch decided to retire and became the company’s honorary president, at which point the company employed around 1,100 workers and annually produced some 16,000 bicycles and over 300 motor cycles and cars.

Johan Puch died of a stroke in 1914, while attending a horse race at Zagreb.

In 1928 the Puch Company merged with Austro-Daimler to reform as Austro–Daimler–Puchwerke, which in its turn merged with Steyr Werke AG to evolve into Steyr–Daimler–Puch in 1934. Gottleib Daimler is credited with the invention of the car in 1889, and the Austro–Daimler Company had experience of producing car over two decades, while Steyr had been established in 1864, and had many decades of experience producing rifles, bicycles, and other equipment.

The green and white chequered badge in the colours of the Steyr town flag was adopted by Puch as its trade mark.

In 1969, Puch launched the most successful product that the company was ever to manufacture, 1.8 million of them: the Puch Maxi moped.

Our featured Maxi SW was registered on 17th May 1985, and a little famously the SW became the last listed pedal Puch moped model after the N ‘Quickly’ model was de-listed in the UK at the end of May 1983; by this time all other Puch models were ‘Mokicks’ with footrests and kickstart.

Following the moped specification change in 1977, Puch had started introduced Mokick models into the UK from August 1977, so it’s surprising that they continued with pedal-start models until the SW was finally discontinued in March 1986.

‘S’ in the Maxi model indicates it has a sprung rear frame to go with the telescopic sprung front forks (while ‘N’ models indicate a rigid rear frame). Being one of the last Puch pedal mopeds, it demonstrates a number of features that would not be found on early models. Obvious items are the roomy 1½ length saddle, which doesn’t really have enough space for a passenger, and the frame isn’t fitted with rear footrests, so not exactly intended to carry a passenger.

The frame is painted in Burgundy metal flake, with gold decals and pinstripe trim, gold finished five-star alloy wheels and original fitment 2¼ × 17 Semperit tyres. The rear carrier seems a significant piece of chrome plated tube work, 18 inches long and mounted from beneath the saddle, with the bottom mountings looping back and round to the rear suspension mountings, where they link up with the chrome plated frame-rail tubes, which neatly continue the tube line down to the top engine mounting.

The rear carrier carries ULO indicators, while front indicators are mounted off the back of the forks below the ULO headlamp; a ULO rear lamp is also fitted. Indicators work from the right-hand handlebar switch left–off–right, while the left handlebar switch works horn–cutout–lights & beam–dip, but there’s no off position for the switch, so you can’t turn the lights off! At tickover the headlamp is dim, and brightens to dull as the revs increase, but it’s hard to imagine it being particularly effective along dark country lanes.

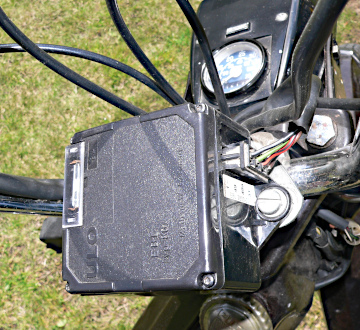

There’s a ULO ‘mystery box’ with a fuse in a corner window mounted on top of the handlebar mounts, which has an internal rectifier to charge a small pack of Ni-Cad batteries. This set operates the indicator system on DC, and charges the Ni-Cads when the engine is running, and when you stop the motor, the indicators still work for a while—does that seem useful? Yeah, we thought that too…

There are also brake light switches built into both front & rear lever brackets, which both work the rear brake light, though its a relatively low wattage so any following motorist is probably unlikely to even notice it during daylight.

Also, we note the horn is labelled 6V DC, and judging by the feeble rattle at low revs rising to a pathetic buzzing that can be barely heard over the exhaust … it should be an AC horn.

The frame serial plate indicates Slo-ped specification “max 30mph”, though the headlamp shell carries a 45mph VDO speedo, so we’re probably not expecting this standard bike to pin the needle on the stop.

The early Maxi exhaust pipe was 22mm (⅞") diameter, but later models had a larger 28mm (1⅛") diameter exhaust pipe to the seemingly same pattern of silencer with traditional alloy baffle. The chrome silencer however is trimmed with a black heat shield.

Fuel tap off–on–res to bottom right, push down the choke lever poking up from the front of the left-hand side panel.

There’s a grip-lock lever under the left lever bracket, which locks the clutch and effects a decompressor in the cylinder head for starting. Still on the stand you can push down on either pedal so the motor spins, release the grip-lock, and maybe the motor starts … or maybe it doesn’t, so rinse and repeat, then success on the second attempt. Because the choke shutter lifts off as the throttle is opened, its best to leave the motor ticking over for a bit before teasing open the throttle, or it might prematurely fade out. Once it’s responding to throttle, then nudge off the stand and we’re warming the motor ready for the road test while waiting for our pacer to get saddled-up.

Hmm, sounds a bit grumbly from the main bearings! It’s a common problem for Maxis to condensate the mag-side main bearing when they’ve been laid up for long periods, and they quickly start growling when the bike is put back into use. It’s not bad enough yet to compromise the performance, but its only going to keep getting worse.

Initial take-off feels quite poor since the clutch seems to fully engage almost immediately, so the motor struggles away against the single-speed ratio until it manages to build up a bit of momentum. The exhaust note appears noisy, so we wonder if the baffles might have been drilled? Full throttle before the engine is sufficiently warmed up results in a lot of four-stroking bluster, which sounds bad and holds back upper revs until the motor heats up and the issue steadily clears.

The bike generally indicates around 30mph on flat at full throttle, and peaks at indicated 34–35mph in light downhill sections, which were tracked by our pacer at an actual peak of 33mph. The noisy buzzing exhaust tone quickly becomes quite ‘wearing’, and doesn’t really seem appropriate for a limited performance moped.

Cheese

Spanish Isolationism

The Puch–Avello story reflects Spanish economic policy in the post-war period. Franco’s Isolationist policy of the 1950s made it practically impossible to import motor cycles to Spain so, as Avello did with MV Agusta, several Spanish companies made licence agreements to build Italian motor cycles in Spain. Things eased a little as the years passed, though Spanish industry still enjoyed a good deal of protection, resulting in the boom known as the ‘Spanish Miracle’. Puch’s investment in Avello was timely as trade barriers dropped and Spain was able to export its products. Franco resigned in 1973, dying two years later, and Avello’s deal with Puch would help it to weather the increasing competition better than other Spanish motor cycle companies as Spain progressed to EEC membership in 1986.

Founded by Alfredo Avello, Avello y Compañía S.L. started operations at its factory at Nataho in the Gijón city of Asturia, as a manufacturer of machine tools, on June 1st 1940.

In 1951 it began building motor cycles under a licence from MV Agusta, from 49cc to 300cc, which were branded as both MV Agusta and MV Avello … maybe you’re thinking that Avello might be a sub-contractor of MV in Italy, but Avello was in northern Spain!

Towards the end of the 1960s, Avello began to distance its business from MV Agusta, which had become more interested in developing large capacity, four-stroke, multi-cylinder motor cycles than in continuing to evolve the lighter, simpler, and cheaper two-stroke models that were of more appeal to the Spanish market.

From this, Avello contacted Steyr–Daimler–Puch as one of the largest Austrian industrial groups, which, among many other products, had been manufacturing a successful and interesting range of mopeds and light motor cycles. On March 2nd 1970, a contract with the Austrians was agreed, and Puch invested in a 50% share of Spanish motor cycle and scooter manufacturer in Avello. Production of Spanish-built Puch models soon began progressing down the very same production lines that were still building MVs.

The first Puch model appeared soon after, as the Trivel Borrasca, which was a moped using the existing Avello Piles frame and a Puch engine. Trivel Borrasca Super and Trivel Plus Terral variants appeared soon afterwards, followed by various other mopeds produced between 1970 and 1972 alongside the MV models, until the MV models ended in 1972.

From 1973, various Puch models came into production at Avello using 50, 75, and 125cc engines.

The Spanish Maxis were imported to the UK in 1973, starting with the Maxi N2 rigid-rear frame model in May ’73, and listed in ‘Brilliant Yellow’ painted finish. This was immediately joined by the sprung rear-frame Maxi S2 in June ’73, listed in a ‘Flamboyant Bronze’ metallic finish.

Both were traditional pedal assisted mopeds, but didn’t employ the expected Austrian single-speed automatic E50 engine! The Spanish Z50 motor featured a manual clutch with two-speed hand-changed gears, twist forward for first, neutral in the middle, and back for second. Underneath the left hand change is a trigger to operate the choke by cable.

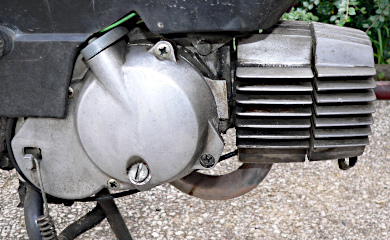

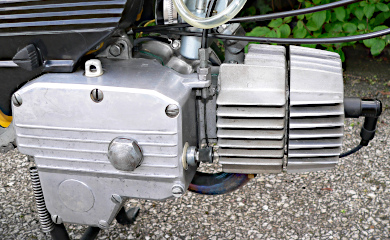

While the E50 motor has horizontally split cases and utilises race bearings, the Z50 motor is vertically split and employs a similar magneto type L17/E20 bearing arrangement as MS and VS fan-cooled models, while the different clutch casings for the E50 pedal-start and later kick-start motors feature ‘rounded’ profiles, the Z50 crankcase and clutch casing is distinctively flat and angular. They’re very different engines.

The standard Z50 engine was the same basic specification as the E50, with 38mm bore × 43mm stroke for 48.8cc, and maybe with 9.2:1 compression, but with 12mm carburettor for maybe 2bhp@5,500rpm.

It’s really difficult trying to find any technical specification information on these Z50 motors.

Our bike is an earlier UK version, N-registered in 1975, with pedals and 17" spoked wheels, while later versions became kick-start with foot rests and alloy wheels. The frame is re-finished in the original yellow colour, but the engine has received a few tweaks with a 44mm Airsal piston-ported cylinder for 65cc with maybe 12.5:1 higher unknown compression (mathematically calculated), but with a 15mm SSF carb for ?bhp@?,???rpm. Sounds like it could be great, but unfortunately the bike isn’t up to a road test because the back pedal rear brake is binding quite badly, so it’s unfit to ride.

Looks nice, but doesn’t work…

Fortunately we’ve rebuilt a number of these two-speed Z50 motors before, and even had one of the ‘Flamboyant Bronze’ S2 models ourselves, so not being unfamiliar with these machines we can fill in the road test gap with a standard 2-speed version…

The Z50 isn’t like the MS50, where you can kick-start the motor over in neutral by standing on the pedals to spin the motor over, then the MS sits there, ticking over, waiting for your next move.

If you spin over the pedals in neutral on the Avello Z50, it just moves forward like a bicycle, and doesn’t turn over the engine.

To start the engine you have to put it in gear, and it’s maybe not best to be trying to start it on the stand. The engine doesn’t have a decompressor, and it’s not so easy to get the motor spinning over because the pedal ratio particularly works against trying to start in first, so generally you’re going to be starting in second, but even in second it’s still difficult to kick-start off the bike without the back wheel contacting the ground. If it does start like this and the spinning wheel contacts the ground, things may not work out so well.

You could also start the bike on the stand by pedalling on the bike, but you need to lean forward to keep the back wheel off the ground, and if the bike has been started like this regularly, the stand is likely to have ‘settled’, so both wheels might be on the ground anyway, in which case you couldn’t even start it on the stand. When the stand gets to this sorry state, it becomes common to put a piece of wood under the stand legs to lift the back wheel off the ground, but that only makes the stand deterioration worse. The obvious conclusions are fix the settled stand, or don’t start it on the stand at all.

The best way to start is to engage second gear, back onto compression (to set the engine in best position start spinning), pull in the clutch and pedal away, then drop the clutch (and trigger choke as required). Generally the bike fires right away, so pull in the clutch and locate neutral to warm the motor.

The later kick-start versions are much easier to start, because you simply kick-start in neutral.

It sounds like a typical Puch, because it’s fitted with the usual Puch silencer.

Pulling away, clutch and locate first (with the usual clunk to engage), feed in the clutch while opening the throttle and the motor pulls strongly. As the revs run out in first, clutch and twist back to second, and the motor again pulls firmly in response to the throttle.

The Z50 motor feels stronger in gear than the single-speed automatic of the E50, which softens the power delivery, though the Z50 isn’t any faster in acceleration due to the time lost in changing gear.

The two-speed hand-change always feels easier to locate gears than the three-speed shift because, whether you’re changing up or down, there’s always a degree of feeling around to find second. The two-speed gearbox becomes somewhat easier because you’re either shifting to the ends of the stops: all the way up, or all the way down, without the need for feeling around for any gear in the middle.

The Z50 also feels as it it delivers better against a gradient since first gear pulls strongly, where the E50 single-speed automatic clutch struggles to find the capability to deliver uphill, which is exactly the same advantage a two-speed MS50 has against a Maxi auto.

Z50 is like riding any Puch Maxi, but with two-speed manual gears and a back-pedal brake.

The rear hub brake effects through reversing of the pedal chain, so when the freewheel is back-pedalled it operates a Bendix through the hub to a gear that turns a cam to operate brake shoes in the opposite (drive side) of the hub. Due to their physics of mechanical advantage, back-pedal rear brakes are appreciably more efficient than hand-lever brakes, and the Z50 rear brake is notably more effective than the usual E50 Maxi rear brake.

Rigid frame N models reportedly handle better than the sprung-frame S models, since the open-backed swing-arm is often criticised for ‘flexing problems’.

UK market Z50 top speed typically indicates around 31–32mph, so performance is fairly comparable to the E50 Maxi, though models were made for different markets and to different specifications, so performance can vary, eg the Netherlands had ‘Snorfiets’ Z50 models limited to 25km/h (16mph).

UK imports of the Avello N2 were discontinued in October 1976, and the S2 was de-listed in December 1976.

Puch Maxi two-speed automatic ZA50 engined models were introduced to the UK from March 1978, till being de-listed in April 1981. The ZA50 was an Avello produced derivative of the Z50 motor, but gained a reputation for a problematic automatic clutch.

Avello production increased steadily from 1,525 in 1970 to over 38,000 units in 1978, in which year Puch brought the rest of the company shares, giving them full ownership.

Despite the popularity of its products, it seemed that Avello had been struggling to post profits for some years and, although sales were reportedly good over the 1982–83 financial year, the Avello company made a loss of more than 200 million pesetas. At the beginning of 1983, the parent Steyr–Daimler–Puch company signed a contract with Suzuki to produce Japanese designed motor cycles and scooters in Europe, and sold off its Puch Austrian motor cycle manufacturing division to Piaggio. At this point Suzuki became a minority shareholder of the Avello factory, contributing 500 million pesetas (36% of the capital), and in March 1984 Avello SA agreed a technology transfer contract with Suzuki to acquire the further remaining 64% shares from Steyr–Daimler–Puch.

In 1988, Suzuki completed 100% acquisition of Avello SA, and changed its name to Suzuki Motor España.

The last Suzuki Maxi was produced in 1995, long before which the product range had progressively drifted from mopeds towards building Suzuki branded scooter models, and later added motor cycles.

With steadily decreasing sales of Spanish market mopeds and scooters, the SME manufacturing facilities were becoming only partly used, and steadily becoming uneconomic.

In 2012, Suzuki announced that it would be closing the SME manufacturing plant in Porceyo, Gijón.2, and the the Avello factory shut its doors in March 2013