When IceniCAM was offered access to a whole load of interesting and exotic Italian sports 50s, we decided to have a bit of a track day with them as a change from the usual road test. The private short-circuit track we’re using on this occasion doesn’t involve any of the usual hill sections of our normal road tests, but that’s OK because of the nature of these machines: the only real relevance is mostly how they perform on the flat around a racecourse.

All these bikes started life as road-going 50cc sports motor cycles (not mopeds), and at the time they were originally sold on the Italian market, would have been performance regulated for highway compliance.

They’ve subsequently received varying degrees of tuning and modification, involving much bigger carburettors, raised engine compression ratios, cylinder porting and exhaust changes, altered riding positions, and changed gearing.

Starting from our oldest machine first, this feels like we’re going right in at the deep end!

The frame is marked ‘IGM 2896 OM Benelli CES*102504*’ which homologation number tells us is a Benelli ‘Sprint’ first series, and was Italian registered on 10 June 1963.

A brief summary of the historical background may help to frame its time…

During World War 2, allied bombing of Pesaro had resulted in extensive damage to the factory, then all the machinery the Benelli brothers managed to salvage was promptly commandeered and transported away by German forces to support the war effort back in the Fatherland, which prevented the business from restoring manufacture until 1949.

The five Benelli brothers fiercely disagreed about the best way to return to production: whether to reintroduce obsolete machines based on pre-war models or take the opportunity to produce new designs. The row led to Giuseppe walking out in a dramatic split from the family business, and across the street to set up his own rival motor cycle concern of Motobi.

Aged 78, and eldest of the brothers, Giuseppe Benelli passed away in 1957, leaving sons Luigi and Marco to inherit the factory and leading to an eventual reconciliation of the family, where Motobi was merged back into the Benelli business in 1962.

Benelli and Motobi now began jointly producing standardised machines, increasingly sharing common motors, frames and cycle components, so the only aspects to differentiate some models of the brands might now be the colour scheme and badging.

Our ‘Sprint’ represents an early example of this time, where both brands had shortly begun to share this same basic Benelli made engine in their mopeds and super-lightweight motor cycles.

The moped motors were given as 40mm bore × 39mm stroke, capacity 49cc at 6:1 compression, for 2.5bhp output @ 6,500rpm. While we can be pretty sure this ‘Sprint’ track racer engine has been progressed appreciably beyond the moped specification, we have no idea of its actual statistics.

The frame is extensively modified with rear-set extensions, which have been grafted onto the lower rails, while the stiffening centre strut seems to have been converted from an integral part of the frame, to a removable bolt-in addition?

The controls are an Ali Saker throttle, and a three-speed shift-change, which we readily discover suffers ineffective gear location as we try to regain neutral just unloading the bike from the van! That’s the trouble with 50+ year-old selectors; they often tend to get a bit tired and vague…

There’s already a whole bucketful of very obvious reasons why this bike would probably never make any sort of practical road bike again, and we haven’t even got it started yet!

The front drum on the right-hand side is empty of any brake-plate; instead a disc is bolted to the blind side of the steel hub with a calliper mounting arrangement fitted off the left-hand fork leg.

The back drum brake proved poor and creaky, but the 320mm front disc with four-pot calliper is obviously more than capable of easily delivering far more stopping power than you may ever dare to try and use on this lightweight machine. Fear that front brake lever if you want to survive!

19-inch chromed steel rims are shod with 2.00×23 tyres, which measure 68 inches long from front to the back rubbers since these are the furthest points as there are no mudguards. Why lights are fitted seems a bit of a mystery, as they’re obviously not connected by any wiring, so they’re never going to light up at all.

The kick-start has a limited 90° stroke, which only turns the engine over one compression, so it’s a matter of jabbing several times until you to get it to catch. The twin fuel taps drain from the alloy tank into a vertical slide 18/8 Dell’orto carburettor, where general starting is certainly helped by use of the choke on this bike, but never required flooding of the float chamber by the tickler button.

The steering stops very much limit the amount of turn you can get on forks, so if you’re wanting to turn the bike in the road at low speed you have to flop it right over on full lock to get round. Any edge on the throttle prompts a snappy motor response, so she picks up and won’t make a tight turn, or hesitation with a touch on the brakes and you’re going to bumping the kerb. This bike has been developed just to go forward as an out-and-out track bike, and is obviously not intended for highway use.

The snappy acceleration is somewhat counteracted by its slow three-speed twist-shift and random gear selection in trying to find second or neutral, on the way up or coming down the box.

While the exhaust note is satisfactorily suppressed by the modern Polini expansion silencer, a loud induction drone and howling revs move into the sound stage as we get underway, while the cycle frame becomes racked by extensive vibration once the revs get up. We’re paced steadily cruising around the course at a gentle 30mph in top, which proves quite leisurely as we settle into the feel of the machine, stretched out along the tank to the clip-on bars, with our feet right back on the rear-sets which are only slightly forward of the rear axle, and feeling for the rear brake pedal for when we might need that later.

OK, we’ve sort of found our riding posture, and cruising around on a parade lap is fine to acclimatise to the bike-but that’s really not what this machine is built for…

Blasting open the throttle draws fuel and air mixture down the gaping bell mouth with a mighty roar, pulling strongly against the top ratio, then soaring into the upper rev-band as the engine climbs onto the porting. Screaming down our first straight run paced at 49mph, we soon discovered the heavily tuned motor seems to be under-geared in top, and feels very much as if it’s revving out, so how fast it might actually go could depend on how much your nerve holds out against the screaming revs.

Motors that rev like this are certainly a challenge to test any rider’s sense of mechanical sensitivity. Dare you try and take it flat out? Or will the engine blow up? Place you bets please…

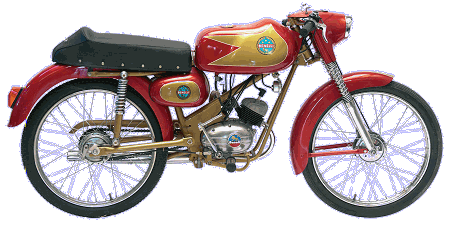

The extensive ‘track’

modifications to convert this bike

into a classic racer have now rendered it completely

impractical

for further road use, but the first series Sprint-50 would

have

originally looked very much like this…

The motor is so highly tweaked that it either needs to be kept on throttle when the engine is hot, to maintain a constant throughput of cooling air/fuel mixture and lubrication, or constantly blipping when the revs drop down, to keep pumping bursts of fuel mix through the motor. We discovered this when switched into neutral to coast into the pit stop with the motor slow running on no load, and the engine nipped up!

It simply gets too hot from not enough through-flow of cooling air and lack of petroil lubrication with the throttle down…

We coasted to a silent stop, notched into second, then nudged the engine back off compression … and it freed straight away. A couple of jabs at the kick-start, and the motor fired up again as though nothing had happened! So, take off again straight away, giving big blips on the throttle to pump more cooling fuel and lubrication through the motor. All seems fine, so we work up the gears again, building up the speed with big bursts on the throttle to maintain maximum lubrication. Building to another flat-out burn with our pacer chasing us out of the top bend, we tuck in for another top speed run down the back straight, which clocks off at 50mph.

This might not seem so quick in relative terms, but for a half-century old 50cc with only three gears, that’s pretty good going considering it seems to be generally set up for best acceleration in short circuit racing. Engine performance is certainly fiery, with a very peaky state of tune on this motor. A change of sprockets could probably find it pulling a higher gear ratio, and going even faster, but that small-finned iron cylinder could do with its generated heat clearing more efficiently to reduce the risk of nipping up.

This Benelli is certainly an old engine that’s living close to the edge!

A couple of laps were quite enough for our nerve to stand, and it does leave you with some wonderment how circuit riders manage to run these sort of bikes round for a series of laps in competition … perhaps we’re getting too old for these toys.

Mario Malanca founded his mechanical workshop at Bologna after World War 2 and drifted into the production of proprietary parts and wheel hubs for other motor cycle builders. Workshop Malanca presented its own first complete motor cycle in 1956, beginning with small-capacity two-stroke models of 125 and 150cc, and fitted with Morini Franco engines.

Morini Franco engines were also employed in Malanca’s first 50cc models of 3M ‘Comfort’ sports motor cycles and Nicky sports mopeds, which soon followed the early motor cycles as production diversified and increased. Malanca motor cycles became popularly adopted for sporting use, which was further promoted as the company began to engage in race competition and off-road events; while expanding sales quickly started to go beyond the home market, for export to other European countries, America and Asia.

Our test example is a 1966 Malanca Nicky Sport 8T model and, while there are Malanca badges on inspection plates on both sides of the engine, this is not Malanca’s own motor, since it was a feature of the Italian motor manufacturers of the ’50s and ’60s where they would brand an engine for the customer. The motor is actually a Morini Franco 3MR kick-start engine with three-speed hand-changed gears, twist back for first & neutral, forward for second & third. An alloy head and iron cylinder are fed by 19mm cross-slide Dell’orto carburettor, which is certainly a larger venturi than the bike would have had as original equipment when registered for highway use in Italy.

The frame is stamped ‘MN 8T*20992*’ on the headstock, but there is no engine number, which is quite common for Italian home market models.

Because these early 50cc motor cycle engines were derived from moped engines, this Morini engine has a left-hand forward acting kick-start with a foot-pedal treadle. The high ratio on this kick-start turns the engine over many times during its action through just a 90° arc, but you can easily bring your bodyweight to bear onto this sort of starter treadle, and it’s actually quite easy to overcome the compression ratio, even without a decompresser.

Fuel tap off–on–reserve, you can shut down the choke slide for on, or flood the float chamber with the tickler button if required, but that doesn’t prove necessary since our Malanca fires up on just the second kick.

The standard road-going silencer effectively keeps the exhaust nice and quiet, leaving the loud induction draw in charge of main noise generation when you open the throttle.

The twin down-tube spine frame gives a firm feel, while the bike measures 70 inches from tip-to-tail, with a fixed 29-inch saddle height, and our scales balance weights at 3st 9lb (23kg) front & 4st 8lb (29kg) rear (total 115lb/52kg).

The 19-inch wheels sport Grimeca alloy hubs with single-leading shoe brake-plates to front and rear. The heel-back brake worked well enough, but only proved effective to operate with your heel for light braking. If you really wanted to stop, then it was better to lift off the footrest and plant the ball of your foot on the pedal—then you could get some more useful stopping power.

Handling was generally well behaved, and the biggest bugbear was having to fuddle around with the twist-shift trying to find neutral and second when going up or down the gearbox (an all too common complaint with most three-speed hand-change shifters).

While the top yoke has a channel across its crown for clamping a set of conventional handlebars, our Malanca now has a sporty set of clip-on bars, however it still retains its standard position footrests, which does make it more difficult to find a natural or comfortable tight-tuck position.

The clutch lever action feels suspiciously light, and proves to be the harbinger of a slipping clutch when the throttle is opened up in second. Knowing this condition is going to make things even more difficult in third, we remove the right-hand inspection plate to check transmission oil and that the pushrod isn’t too tight on the pressure-plate, but that seems OK, so the problem appears to be about weak spring pressure somehow. There doesn’t seem to be any obvious means of increasing pressure on the plate, so we can only hope we may be able to overcome the clutch breakaway by a steady build up of speed and light throttle usage.

Despite conservative use of the throttle, it just didn’t prove possible to transmit full power on the flat, and the best we could coax the Malanca up to was 41mph, as opening up the throttle only produced screaming revs from the slipping clutch. Exploiting a long and gentle slightly downhill stretch on the circuit, our pacer managed to clock us up to 48mph, though we still couldn’t use full throttle as the clutch would still breakaway at full opening. Our conclusion was that the Malanca would probably pull over 50mph OK with a good clutch.

Despite its tuning conversions, this Nicky Sport still manages to maintain the look of a nice classic 50, but the ‘mandatory’ clip-on handlebars rather tend to inhibit any comfortable riding position with its standard position footrests.

During the 1960s Malanca established a new factory, including an engine manufacturing plant to machine and assemble its own motors, which were characterised by a ‘Red Head’ to the cylinder.

Popularity of the 125cc capacity prompted the development of a new two-stroke twin model in this displacement, which was presented at the 1973 Paris Show. As first orders of the E2 were delivered to dealerships for the 1974 season, a fire at the factory destroyed the assembly unit and manufacturing plant, so production was dramatically interrupted while the facilities were rebuilt.

New versions of the 125 twin were presented again in 1976, as the E2C ‘Tourist’ and E2C ‘Sport’, and a first model E2C 150cc.

In 1978 Marco Malanca inherited management of the Bolognese factory from his father, and listed the business on the stock exchange as Malanca Motori Spa, while production mainly focussed on street racing sports 125cc models.

1979 launched a new GTI-125 model, and GTI-80 in 1980, during which period the company transferred factories to a completely new 6,000m² plant in Pontecchio Marconi.

The early ’80s brought a confusing range of constantly changing 125cc models, which actually proved quite popular for their ‘individuality’ as early ‘factory built custom’ machines, and 1985 introduced a new Mark-125 Enduro model.

While the 125 capacity seemed successful, the company decided to invest in research and development toward re-launching the 50cc category; however an unexpected slump in sales appeared to compromise the business, so Malanca closed its factory and divested the brand in 1986.

Our third ’60s track racer is a ViVi SaS ‘Special’ 50; its old Italian log book dates the bike at 22 June 1968.

The history of this make originates from the metal pressing company Viberti of Turin, who produced body components for trucks and buses, and subsequently were absorbed into the Fiat Group.

In 1956 Viberti contracted a partnership with the Victoria Company of Germany, whereby Viberti would produce a pressed-steel frame designed by Bruno Müller, to mount Victoria’s M51 engine.

Both companies agreed to market their own branded derivations of the same machine, Victoria selling their model as the ‘Tourist’, while Viberti presented their version as the ViVi (Viberti–Victoria) at the Milan Cycle and Motor Cycle Show in December 1956.

The ViVi’s launch was bitterly protested against by other Italian moped manufacturers who were still making machines with traditional tubular frames by brazed lug construction methods—compared to which, the lightweight ViVi’s pressed-steel frame was markedly cheaper.

Some voices suggested that the aggressive low pricing of ViVi was orchestrated by the Fiat Group and would compromise the motor cycle market; they demanded its expulsion from the show for unfair competition …but the event went ahead anyway.

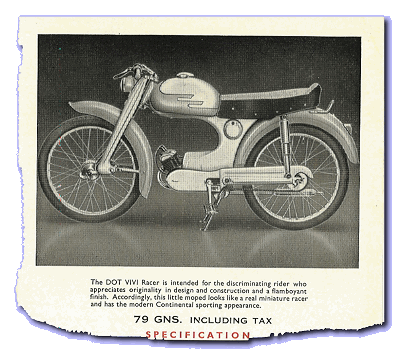

Dot Vi-Vi ‘Racer’

Still characterised by further pressed-steel frame derivations of the moped design, other Viberti machines followed: the ‘Furgoncino’ moped, ‘Turismo’ and ‘Gran Turismo’ models, a ‘Carro’ three-wheel transporter, ‘Scooter’, and various motor cycles, but despite an extravagant promotional campaign and favourable terms, the range somehow failed to achieve the desired mass-market impact.

In 1958, Victoria merged with DKW and Express Werke AG, to form the Zweirad Union, which maintained the Victoria name on its continued Vicky mopeds and small motor scooters.

The Victoria Vicky III-N, IV two-speed & IV three-speed were de-listed from August 1959, to be succeeded by new Luxus models, which still used the same Victoria engines, allowing continuity of ViVi production.

Dot Cycle & Motor Manufacturing Co Ltd of Arundel Street in Manchester also factored in a range of various ViVi models from 1958, starting with the Moped, Road Racer (two-speed), and Scooterette, then adding the Grand Tourer moped and three-speed Road Racer in 1959. The Grand Tourer seemed to become the De-Luxe three-speed moped for 1960, and the Road Racer two-speed was dropped. In 1961 the Scooterette was de-listed, and the range was joined by a dramatically expensive three-speed Monza Road Racer.

Only the two-speed Dot ViVi moped remained listed for 1962, and that concluded at the end of the year. All models were based around versions of the 49cc Victoria engine.

Victoria Luxus models continued to December 1962, when they were replaced by other standard Zweirad Union group branded products with proprietary Sachs engines, which were also sold with DKW badges.

This decision back in Germany ended the supply of engines to Viberti in 1963 as remaining stocks were exhausted, and the unique design of the Victoria engine meant that no other motor could be readily adapted to fit the frame, so that was the end of the line for the ViVi.

While most of Viberti’s motor vehicle press parts assets were retained by Fiat, remains of the former motor cycle business were divested from the group. The license of the ViVi name and its equipment was sold and moved to re-establish at Pontevico, where the new company continued to produce more traditional tubular frame motor cycles with Minarelli engines, also designed by Bruno Müller, but now under the name of Vi-Vi SaS.

Dimensions of our ViVi SaS ‘Special’ 50 measure at a relatively stubby 64 inches long (due mainly to having a short rake angle at the headstock), with a low 27-inch fixed saddle height, and weighing in at a relatively solid 4st 2lb (26kg) front & 4st 10lb (30kg) rear (all-up 124lb/56kg).

Tyres are 2.00×18 front and 2.25×18 rear, on alloy rims laced into proprietary market steel hubs.

The duplex cradle frame offers a firm mount for the Minarelli P4 motor with right-hand kick-start acting in a backward arc (earlier P3 motors had a left-hand kick-start acting in a forward arc). Gear pattern shifts one-up/three-down due to having a reversed lever for the rear sets. The clutch lever proves to have an unusually heavy action for such a small engine, and the foot gear-change has an equally heavy shift, requiring a firm press to select—particularly so for first.

The steel fuel tank is another proprietary market item that can be found on other makes of the period, with an LSM sport seat covered in a style that very neatly matches the paintwork and follows perfectly the rails of the frame.

The Minarelli P4 early type round crankcase is fitted with a square finned iron cylinder and alloy head. The motor components look all correct on this classic machine; however the bike was originally rated at 1.42bhp for Italian road use at the time it was registered, its performance limited probably by the fitment of some miserable 8 or 10mm carburettor. Now it wears a Vertix fast-action throttle opening a 19mm cross-slide Dell’orto, and exhausts into a Sito expansion system, mercifully suppressed with a fitted baffle.

The rear sets certainly weren’t standard equipment, they’re a much later aftermarket fabrication and the location for the original footrest position can still be seen with the lugs beneath the middle of the engine.

The front brake-plate looks as if it has a big air-scoop for cooling, but that’s just cosmetic fakery, because the vents are all blank and the back is hollow cast.

All seems reasonably practical and ready to go, so on with the fuel, probably try it without choke first to minimise any chance of flooding, a couple of jabs at the kick-start, and she fires right up to sound fairly civilised by comparison to some of the other track machines we’ve tried (as you’ll discover in the next chapter).

Because of the iron cylinder, we hold the motor running for quite a while, feeling the temperature working through the cold metal until the heat creeps through, and we’re more comfortable the tolerances for fast running will be thoroughly settled.

Out onto the road, we join our pacer, then ease away in first on about half-throttle, at which we’re pleasantly surprised to discover it actually develops some useable torque in the lower range. Into second and build up a little more pace as we try and settle into some sort of practical position between the clip-on bars and rear-set pegs, only to discover the café-racer saddle also comes with a sprinkling of crushed nuts. That’s invariably one of the problems with sport bikes: they’re often a bit sparse in the comfort stakes.

Winding the throttle beyond half-open begins to generate that familiar induction wail, and you can actually hear it with the ViVi because it’s not drowned out by the exhaust tone, which remains pleasantly conservative thanks to the baffle.

The front brake seems to work OK, but the cable operated rear footbrake develops a lot of travel to the pedal, and proves quite ineffective at the drum. It might have been more efficient with the factory footrest arrangement and probably a longer original pedal, but the shorter rear-set pedal doesn’t seem to have done its operation any favours.

Best on the flat was paced at 51mph, but to get the motor to pull up to that speed required the revs wringing up to everything you could out of it in third, before switching into top, because fourth seemed a little over-geared for the output of the motor. If you changed up too early, then the engine couldn’t seem to pull past 45, just needing that extra urge to get the revs in top onto the porting, then we wailed down the straight like a frenzied banshee as induction roar from the carburetter reached suction fever pitch.

The CEV 120km/h speedometer didn’t work, so we had a look into that, and no, it probably wouldn’t work with no inner cable in it.

Our ‘Special 50’ was probably built among the last of ViVi SaS production, as the company seemed to have ceased manufacturing in 1968 … and quietly faded away into the forgotten cloud of obscurity.