As with many ancient manufacturing concerns, most of their stories become lost in the veil of time, but we try our best to unravel the past…

The summer of 1889 brought together four Saint-Etienne businessmen with a common passion for mechanical transportation devices. Messieurs Pichard, Montet Chavanet, Claudius Gros, and Pierre Lapertot formed a professional society they called Société de Constructions Mécaniques de Cycles et Automobiles as a forum to exchange ideas on their vehicular interests of the time, in bicycles, tricycles and quadricycles, being either manpowered, or propelled by an engine.

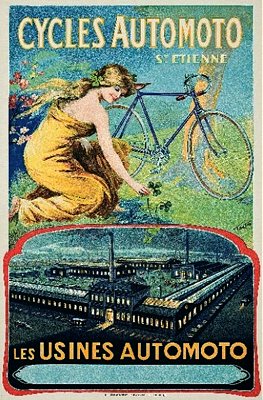

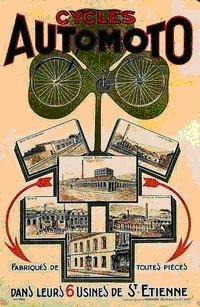

Cycling in France largely originated from the Saint-Étienne region, giving rise to a number of prominent cycling designers and notable industrial manufacturers in the area, and leading to the city becoming popularly referred as the country’s cycling capital.

Over the following decade the group was joined by other members, Messieurs Goudefer and Pégout, who brought further ideas and contributions to the Société. In 1898, Gros, Goudefer and Pichard registered the Automoto marque for the sales and distribution of cycle and voiturette components. In 1899 another business was registered as Société de Construction Mécanique de cycles et automobiles Chavanet, Gros, Pichard et Cie for the purpose of manufacturing bicycles, tricycles and voiturettes.

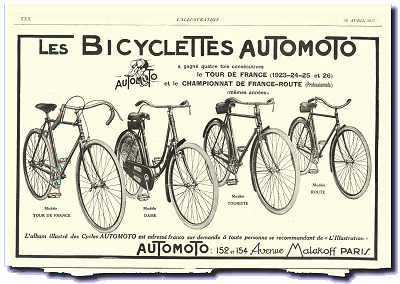

In 1901 the business was listed as a limited company under the revised group title of Société Anonyme de Construction Mécanique de la Loire (or CML), producing Automoto motor carriages, and also selling under the brand of Svelte. All very grand and ambitious titles, but trade didn’t seem to go so well, as the business filed for liquidation in 1907. In 1908, the company restarted under another new title of Société Anonyme Nouvelle de Construction de la Loire Automoto, but abandoning car manufacture to concentrate on cycles and motor cycles. Not until 1910 did the company adopt its final name of Cycles Automoto and brand its products with the three-leaf clover emblem.

After the First World War in 1919, Automoto became a member of the consortium La Sportive, which engaged in the regrouping of French marques, including Alcyon, Armor, Automoto, Clément, Gladiator, Griffon, Hurtu, Labor, La Françise, Liberator, Peugeot and Thomann.

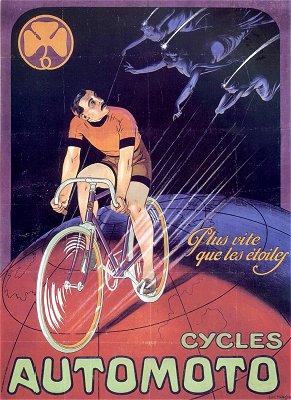

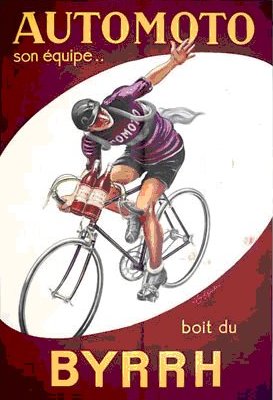

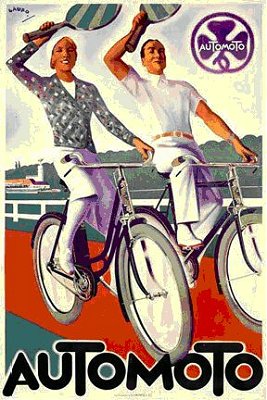

Automoto developed into one of the most prestigious marques of French cycling in support and competition of the greatest cycle races of the time, its works teams famously competing in the colour violet.

The Automoto factories also produced a range of motor cycles up to 500cc, initially using their own engines, later favouring the fitment of proprietary motors from Aubier–Dunne, Blackburne, JAP and Peugeot.

Having established a reputation for quality cycles and motor cycles over a decade of success, Automoto’s products had placed it toward the upper end of the market, but this sector became particularly affected by a dramatic loss of sales with the advent of the Great Recession at the end of the 1920s. By 1930 the business was beginning to struggle as many of its customers began feeling the pinch, and economising with the purchase and use of budget machines instead.

Automoto was trying to sell the wrong products at the wrong time and, unable to sustain the operation through such difficult times, Peugeot seized the opportunity to acquire the business for a snip in 1931—then immediately turned the manufacturing to production of smaller economy machines up to just 250cc and using proprietary engines.

After World War 2 the company continued mainly producing utility motor cycles with Villiers and AMC engines. The range of bicycles also was extended beyond exclusive models for the racing elite; Automoto cycles became available in both ‘mademoiselle et monsieur’ frames in leisure and utility classes, ‘Le Grande’, ‘Ballon’ and ‘Demi-ballon’, ‘Tourisme’, ‘Course’ and ‘Demi-course’, ‘Randonneur’, and even ‘Porteur’ (Trade Carrier) models.

Now, over twenty years since Automoto stood proudly at the pinnacle of competitive cycle racing, the brand was becoming diluted in the pursuit of general commercial market sales, which even now reached as far as some North American exports.

Into the 1950s the increasing popularity of cyclemotors, and subsequently mopeds, found Automoto-branded machines in these utility categories, built with Marquet, Motobloc and VAP engines. Our Automoto model CCV moped features a VAP engine, so gives an opportunity for another historical introduction…

The first VAP cyclemotor was produced in 1942 and designed by Pierre Verots. This was a 53cc engine that mounted alongside the rear wheel of a bicycle, and built by the company La Bougie BG.

The name VAP stands for Verots–Androit Propulseur (Pierre Androit was the head of La Bougie BG, and the company shortly became ABG following merger with another business called Ariés. Since ABG was located in the Paris region of occupied France, practical VAP 1 cyclemotor engine production didn’t commence until 1945. How many of these VAP 1 motors were made isn’t really known, maybe up to serial 5,000. 1946 brought an evolved 51cc VAP 2 cyclemotor engine, which was seemingly only made in small quantities, possibly as low as just 500 units from serial 5,000, when the 48cc VAP 3 took over in 1947 from somewhere around serial 5,500. The VAP 2 and 3 engines practically only differed in the slightly reduced capacity to comply with French 50cc cyclomoteur legislation of the time.

The direct-drive VAP 3 engine ran through to around serial 33,000 when it was replaced by the VAP 4 in 1948 with flywheel magneto electrics, clutched transmission, and final chain drive to replace the earlier pinion driven ring gear. The VAP 4 engine remained in production until 1956, was the most prolifically produced VAP attachment motor, and also sold into various export markets. Some French manufacturers began to offer VAP 4 powered cyclomoteurs as complete machines, the most significant being the Peugeot PHV-25 mixte framed cycle of 1949, as well as other ‘Davy’ and ‘Puma’ branded moped-style VAP 4 powered models.

The association with Peugeot led to the development of the VAP 5 roller-driven motor for mounting beneath a cycle bottom bracket, made exclusively for Peugeot in 1950 to power their BMA25L and BMA25GL models. The BMA25 was marketed under several Peugeot-owned brands as Aiglon, Automoto, Griffon, Météor, Peugeot’s own label, and Trophée de France.

The BMA25 range was only sold for one year, then replaced by the Peugeot Bima range in 1951, engines for which were produced within the Peugeot group.

Though a few installers had used the chain-driven VAP 4 as a moped motor, up to this time all VAP engines had been designed as moteurs auxiliaries; 1952 introduced the company’s first purpose-built VAP 4/DT 1.75bhp moped motor with ‘Double-Transfer’ porting, a carburettor at the back and exhaust at the front. This preceded the subsequent series of VAP-A, VAP-B, and VAP-G moped engines in 1954; their model letters don’t really represent any model order, but just happen to be derived from the company name.

The VAP-A was a simple single-speed and direct drive motor that was only made in 1954. The VAP-B was single-speed with a manual clutch available until 1956, and VAP-G was a clutched two-speed motor, which continued up to 1958.

VAP 55 and VAP 55/3 model engines were introduced with flywheel magnetos, and derivative VAP 57 and VAP 57/3 motors with Magnéclair ignition generators brought out in 1957.

The Magnéclair electrical set was a somewhat unconventional device for the period, in having no conventional external rotating flywheel, so the rectangular generator cover appears more like a small plastic box. The system features conventional contact points with coil ignition, but operates inversely as the permanent magnetised poles remain static, while a small rotor rotates within them. Flywheel effect for the engine is regained by a formed metal strip around the outside of the centrifugal clutch housing.

The miserable Magnéclair lighting coil is specified to drive a 6-Volt, 1-Amp (6-Watt) headlamp and 12-Volt 0.5-Amp rear bulb, which might just about raise a dim glimmer in the yellow coated, anti-dazzle, French market headlamp bulb, but you certainly shouldn’t expect to see anything by this completely ineffective illumination since it’s only classed as cycle grade ‘marker lights’ to merely be seen by.

The VAP 57 engine first arrived in the UK when subjected to testing and evaluation by Elswick–Hopper in some of their prototype mopeds in the 1958. Dunkley, Mosquito, and two-speed Trojan moped motors were all tried and rejected in favour of the VAP engine, which went on to further testing at the MIRA proving grounds in July 1959. The MIRA test model mopeds were subsequently developed into the two Lynx moped prototypes that were shown at Earls Court Motor Cycle Show on the Scootamatic stand 83 in November 1960. Formed by the management of Elswick–Hopper, Scootamatic was a company specifically set up to handle sales of imported mopeds and scooters into the UK. The Lynx project never progressed to production, and Scootamatic chose to factor through a range of AutoVAP mopeds instead.

Since our Automoto CCV model shares the same VAP 57 engine and VAP belt flywheel set, it’s probably not unexpected that the moped shares some aspects of the AutoVAP, but several more of our Automoto features also look remarkably similar to some of the AutoVAP models, and there appears to be a degree of badge engineering going on here.

Our Automoto headstock features the classic ‘Cloverleaf’ branded badge, while the stem bolt holds down an aluminium owner plate, hand-stamped A.Texier. Sauze.Vaussais. DS, which gives some flavour of the bike being originally sold into its home market. The remains of dealer decals grace the front and rear mudguards, which are semi-valanced to reduce spray.

The continental market Catalux 6 rear cycle lamp features red lens and reflector only, since the French regulations of the time considered the Automoto much as a bicycle, requiring no white port for registration plate illumination. The 90mm Soubitez headlamp is equipped with an interesting design of V-shaped lens, maybe some eccentric optical idea to obtain a better performance from the sizzling, single-filament 6-Watt bulb? A speedometer port in the headlamp shell is filled by a blanking plate marked ‘Compteur ED Veglia’—and we won’t be getting any useful readings from that, so it’s back to the pace bike again. Automoto came from the days when speedometers were considered luxury accessories rather than essential standard equipment! The lights are engaged by a simple rotary switch, just turn through 90° for on, and that’s the full extent of Automoto’s technical equipment—virtually nothing!

A lever fuel tap switches off–on–reserve, while choke on the Gurtner D12mm carburettor is clicked on by a raised tab on the top of the carb, push down to engage, and the shutter will snap-release as the throttle is opened. The wire gauze air filter butts closely up against the inside face of the right-hand side panel, and a small crescent cut-out allows part of the top of the filter housing to protrude and breathe from the outside world.

A decompressor operated by a little thumb trigger below the throttle twist-grip easily gets the motor spinning and stops it with a loud twittering noise when you’re done, since this decompressor unusually vents into the open air (most decompressors vent into engine exhaust ports so you generally don’t really hear them as obviously as the VAP motor).

Moving Automoto around is markedly different from the typical handling of a comparable Mobylette. With drive mode engaged, Automoto normally freewheels backward, but doesn’t go forwards without turning the engine over! The reason for this is the drive to the motor is engaged on a ratchet, so you generally need to engage the decompressor to aid forward movement since the motor doesn’t readily turn against compression.

The VAP flywheel however, features a drive engagement mechanism which is easily changed by simply clicking a disc-switch in the middle of the flywheel, then you can wheel the bike lightly about in pedal mode, while the Mobylette is handicapped with a wretched fiddly engagement switch on its flywheel that either tends to jam or self disengages, so everyone is very loath to mess with it!

Initial take-off is invariably best aided by some light pedal assistance as the single stage automatic clutch locks in quite readily and the motor really struggles at low revs. This arrangement is likely to become particularly reliant on the rider for hill climbing if the speed has dropped away.

The motor however proves much more capable once it’s managed to pick up a few revs, and pulls quite strongly thereafter, up to a steady cruising pace around 28mph. The ‘open ported’ carb is surprisingly unobtrusive in its intake draw, the laminated wire gauze filter proving remarkably effective in damping out induction roar.

Our pacer clocked best on flat at 34mph, in a crouch with light tailwind. With runaway revs, our downhill run paced at 38–39mph, the VAP engine proving far more capable of handling this than you’d probably expect. Charging the uphill section initially found revs expectedly falling away due to VAP 57’s relatively low compression ratio, but halfway up the climb we experienced the revs unexpectedly rising as a slightly slack drive belt began slipping under load on the front pulley, so the paced 18mph cresting the rise wasn’t really very representative.

Returning to base, we re-adjusted the drive belt tension and returned to rerun the uphill section, now with a result of 24mph cresting the rise—much better! The VAP motor dug in well to attack the incline, and just goes to illustrate how it’s worth maintaining the correct service or performance will drop off.

The big full-width Prior alloy hubs provided very good braking performance throughout.

The 2.00×19 Continental whitewall tyres maybe add a little period style, but contribute more fashion than comfort to the ride. The telescopic ‘grease’ fork set is undamped and effectively only present for shock springing, while the combination of rigid rear frame and the Lamplugh sprung saddle delivered a very Spartan ride, for which anyone would be much relieved to get off as soon as possible.

An electric horn is fitted, but not wired up, so a fallback bulb hooter is mounted on the handlebars. A toolbox is mounted between the saddle tube and rear mudguard. Just one thumbscrew secures each side panel, providing easy and ready access to very little behind them! The bike is so basic that the carburettor is practically the only thing behind both side panels.

The centre stand is one of these ‘spring up automatically’ types (exactly the same as AutoVAP), which can become rather an irritation when you’re shuffling the bike about the garage and trying to position it, since you have to either hold the stand with your foot all the time, or keep constantly pushing it back down.

The side panels seem fairly ineffective at sound shielding, so quite a bit of mechanical motor noise comes up at the rider.

The Automoto brand began to wind down from 1959 when Indénor, a subsidiary of Peugeot, acquired control of the Automoto and Terrot brands and immediately initiated steps to conclude both companies. Indénor had closed down the Terrot factory at Dijon by 1961. All production at Automoto’s Saint-Étienne factories had ended by 1962. The sites were closed and many units subsequently demolished, largely for housing development, though some of the old factory buildings still survive and remain in use by JTEKT, as a producer of automotive components.

The VAP 610 engine was introduced in 1961 to replace the VAP 57 engine, though Scootamatic continued selling a reduced range of AutoVAP VAP 57-engined mopeds into 1963, just the Caravelle and Caravelle De Luxe, but these last two models were discontinued by the end of the year.

The VAP 610R disc-valve engine replaced the 610 in 1962, though this motor was of reduced power to suit French market cyclomoteur legislation of the time. The 610R motor was manufactured until 1966.

The last VAP engine model was sold in the VeloVAP cyclomoteur produced from 1959–69.

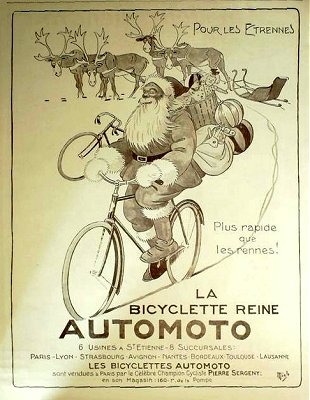

The Automoto mystique still lingers in the air like a classic scent of cycle racing heritage. Genuine competition built Automoto racing cycles from the sporting period now attract unprecedented premiums from collectors of the genre, while company artwork and reprinted period posters are also enjoying a renewed appreciation by cycle & motor cycle enthusiasts, and as popular urban décor.