Local legend tells of an ancient smoke-belching beast roaming the Anglian borderlands. This largely unexplored and uncharted region lies deep within Iceni tribal territory, so tracking down this mythical creature (even if it may exist at all) could involve a most perilous quest. Our expedition mounts up to travel north into the great wilderness, guided by no more than generations of folklore, till we happen upon a hunched figure squatting across a stile.

He raises his hooded head as we approach and stares straight at us with the wide bulging eyes of a madman, ‘Go back, back!’ He gestures, ‘Do not enter this place, for here lurk monsters!’

‘But it is the monster we seek!’

He looks confused, and ends the conversation by turning his back, walking away, muttering and shaking his head.

Pressing onward into the rain, through dark forests, and squelching across swampland, to finally arrive at the island of Horham, rising from the bog.

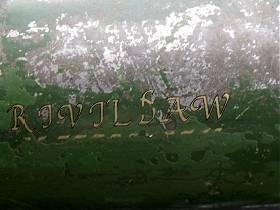

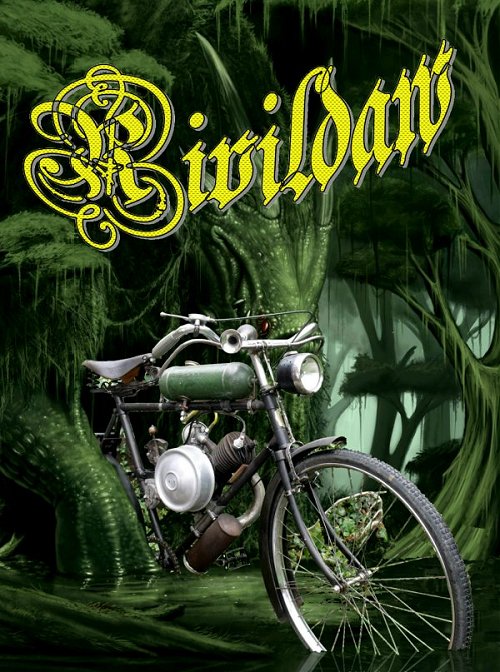

Barely touching our feet upon the firm ground of the shore, we are startled and afeared as a mighty smoking beast of fire & steel bursts forth from a hidden cave, and charges straight towards us—behold, Rivildaw!

Confronted already with our fearsome adversary, we must quickly assess its construction in preparation for battle.

Sizing our formidable prey with the single glance of professional and experienced monster hunters, the pressed brass badge on the headstock tells us this behemoth is based upon a Rival gentleman’s bicycle, made in Norwich, with a 22-inch frame.

The frame space is mounted with a Villiers 98cc Midget engine, a type commonly fitted into old lawnmowers, but also used in some pre-war lightweight motor cycles.

The familiar glint of an alloy casting beneath the motor is immediately recognised as the engine mounting from a Raleigh RM1, so what we’re facing here is not one single beast, but some twisted homogeny of several creatures. Primary drive is by chain, to an Albion gearbox, forward for first–neutral–back for second, but horror on horror—there is no clutch! What manner of brute could still be crash-change in the 21st century?

Final drive is by V-belt to a rim clamped against the rear wheel spokes, but this looks to be some recycled early moped wheel with half-width hub, since the rim/tyre size is 26×2, with a redundant final drive sprocket whirling around the brake plate. We’re almost thrown by a pedal freewheel fixed to the right-hand hub side, but after much puzzling manage to recognise the component as an adapted Quickly wheel. The rear hub is operated through a converted linkage to the conventional cycle rod brake system, while the right-hand rod set is retained to work the original front stirrup with blocks onto the rim.

The front wheel is old cycle sized 26×1-3/8 with a Raleigh Record tyre on the Westwood pattern rim.

The carburettor is a Villiers 9/16-inch brass cast body, which appears to be of lawnmower origin, adapted to the near horizontal inclination of the engine by the fitment of a secondary cast aluminium manifold to keep the float bowl level.

The intake is closed by a 3-3/8-inch diameter gauze covered alloy bell mouth screwed to the flange.

The right-hand of the engine mounts a 7-inch diameter brass flywheel with alloy mag cover, but no internal HT, so taps off the lighting coils to an externally mounted HT coil above the gearbox.

The gearbox is connected to a gate-change selector just above the HT coil, with gears located by a small lever arm topped with a wooden ball knob.

The pressed-steel Summit pattern rear carrier looks suitably period 1930s, and the top frame tube is crowned by an Atco lawnmower ‘barrel’ petrol tank, with an old leather Brooks saddle on the stem.

Headlight is a VEC flat-back, but what looks like a rear lamp on the rear mudguard is in fact an antique Desmo red glass lens reflector in an alloy case. The actual rear light is a small cycle lamp clamped to the right-hand rear stay, though the seeming absence of any wiring might suggest the lighting isn’t actually hooked up—unless it operates by mystical forces?

The old style cycle mudguards are side shielded for effective weatherproofing, and serve to further compliment the appearance of antiquity.

Rivildaw cuts an awesome apparition, but now we must attempt to mount and tame this fearsome brute, and there’s no suspension, so you just know this is going to be a rough ride.

Measuring 41 inches tall to the saddle top, Rivildaw stands dauntingly high on its Suresta XL centre stand, with 5½ inches clearance beneath the rear tyre. Rolling off the stand actions the legs to close in, ready for flight and neatly within the pedalling arc. Even off the stand, Rivildaw’s saddle still measures 36 inches to the ground, which is way taller than our hunter’s inside leg, so mounting this monster is going to require a leap of faith—and it’s going to be a long way to fall if we get it wrong.

Lever the fuel tap below the right-hand side of the tank, then study the carb to figure out where the petrol goes next. We’re tempted by a flood button to the upper right, but also notice a choke shutter tucked between the filter, up for on, but once you’re on the bike this would look pretty difficult to access and open, so we give it a miss and tickle the flood button instead.

The Raleigh ‘North Road’ pattern handlebars have only one simple Villiers lever throttle control of seemingly lawnmower origin … so how might the decompresser work?

A glance at the cylinder provides the answer, the decompresser just has a button head on the valve, so how easy is that going to be to operate while you’re pedalling the bike? No, you’re right; it’s going to be impossible!

Ok, we’ve got a plan! Run along with the bike, jump on (and pray we don’t fall off), pedal up to speed, reach down with right hand and switch into second, keep pedalling, open the throttle and hope it starts….

Surprisingly the plan works first time, and Rivildaw gargles into life … so now what? We hadn’t thought beyond this!

Notching out of gear seems like a good idea, then we can run the engine to warm a little before the main event on our bucking bronco, but as we brake to a stop beside the pavement, are uncomfortably reminded of the difficulty of a 36-inch saddle height with a 30-inch inside leg—so opting for the immediate dismount…

Continuing to run Riv on the throttle, the top run of the primary chain is covered by a reversed cycle guard, but the exposed return run gnashes angrily around open sprockets, while a drive boss whirls furiously through a clearance port to the front of the guard.

The exhaust can suppresses Riv’s growling better than we might have expected, but it still sounds rather annoyed at being disturbed.

We’ve now hatched plan-B as to how to get going, run along with the bike, jump on, pedal up to speed, notch forward into first, then open the throttle and see how fast it’ll go in low gear…

This manoeuvre was neither confidently nor stylishly accomplished, and we were just grateful to have executed and survived this hazardous effort even in some worrying and wobbly manner, though this led our pace bike rider to very quickly drop back out of the combat zone until we appeared to have mastered the situation.

The pace bike eased cautiously up beside to report a max of 20mph in first, to which we replied ‘OK then, going for second’, at which out pacer dropped dramatically back again to a safer observing distance. Throttle back, then fumble down with your right hand to find the gear knob, notch back for second, back to the bars and go for full throttle-up (in true space-shuttle style).

Second is an appreciable ratio jump, and we do momentarily wonder how fast this monster might run?

Piling on the throttle lever in top really pours on low frequency vibrations, while Rivildaw’s cycle frame is bucking and kicking from its rigid chassis on the rough and potholed track.

Up ahead we see a family of pheasants crossing the lane, so start frantically hooting the bulb horn till they flee into the hedgerow to escape the rage of our fire-breathing monster.

Somewhat gratefully, our speed seems to level out at 27mph along the flat as the Midget engine doesn’t develop enough power to pull any more revs in top. Rivildaw seems over-geared and underpowered: the lawnmower engine has given its all.

This seems to have been quite enough worry for our pace rider, who signals for home, so we throttle down, notch back to neutral, and pedal though a turn in the road. This is a far safer and manageable means to accomplish such a manoeuvre than in-gear and under power.

Riding without a clutch doesn’t actually present much difficulty, though we’re not sure it’d be so easy in traffic.

Pedal up to speed, notch into first, accelerate up to pace, throttle back, notch into second, throttle up again, and just when we think we might be getting the hang of this: Riv starts messing around with a bout of misfiring and intermittent ignition. We’re forced to notch back to first and pedal assist to keep the spluttering motor going … then all the vibration and shaking finally rattles off the air filter, which is promptly run-over and flattened by the pace bike.

We cough and chug back to base, and call it a day, grateful to have battled and survived another truly monstrous encounter.

The single-speed pedal freewheel enabled cycling range up to 15mph, but pedalling Rivildaw is no easy task: the mag-set obstructs the pedal arc on the right side, while the air filter bell-mouth and whirling drive boss on the crankshaft protrude to the left. It really needs cranked pedal arms to make this essential operation easier, while a cable operated decompresser that could be effected from the handlebars would certainly be a useful operational control to add.

The decrepit ignition set severely hampered functional use, as did the improvised inlet manifold, which tended to rotate the carb clockwise with the vibration and disable the fuelling. The vibration similarly could engage the choke shutter, also resulting in disparate running, and all the difficulties recounted rendered Rivildaw an extremely difficult mount to get a clean and effective run to assess.

An interesting and distracting diversion, the bike shows a great deal of promise, but demands ongoing development to offer any prospect of being even remotely practical.

The brakes seemed surprisingly capable on the test, though on reflection, stopping may have been among the least of our concerns during the ride.

The Midget engine has a cast iron cylinder with one-piece radial finned head and deflector top scavenging, through piston ported inlet, single transfer and side exhaust … though we’re somewhat puzzled as to the purpose of a wooden wedge driven between the cylinder fins and frame down tube? We could only imagine this was intended as some vibration damper—the only observation we might add was that it didn’t seem to work!

Rivildaw is a true mechanical Frankenstein’s monster, built from a wide selection of odd components. Its name derives from a compilation of its Rival Norwich built cycle frame, Villiers engine, and the initials of its creator D A W.