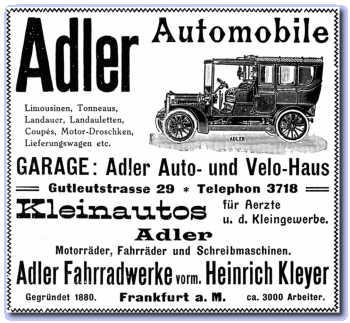

Entrepreneur Heinrich Kleyer (1853–1932) first started his business in the late 1870s as a small machine shop in Frankfurt am Main, and selling early bicycles imported from England. The Adler works was formally established on 1st March 1880 as Germany’s first cycle constructor, beginning as a tricycle manufacturer at a time when the art of cycling was quite in its early years, and adopting an Eagle for its logo—Adler being German for Eagle. Tricycles soon were joined by bicycle manufacturing in 1881.

In 1886 the rapidly growing company was re-titled as Adlerwerke vormals H Kleyer AG and brought the first ’low-gear‘ bicycle onto the home market. The following year, Kleyer bought a large 18,000m² site on Hoechste Strasse, upon which he would start construction of a massive complex of new factory buildings in 1889. Maintaining an eye for innovative ideas and keeping his cycle business at the cutting edge, Kleyer also introduced John Boyd Dunlop’s 1887 invention of the pneumatic tyre to Germany.

In the 1890s the company began manufacture of a highly successful line of thrust-action typewriters based on an original design by the American inventor Wellington Parker Kidder. These were first marketed in Germany from 1895 as the ‘Empire Typewriter’, later becoming the ‘Adler-7 Typewriter’.

The Adler factory in 1900

Adler’s first link with the automobile world came with a contract to supply wire wheels for Benz Velo-motor carriages, during which period Aachen engineer Max Cudell had contracted a series of French licences to build De Dion–Bouton engines in 1897, tricycles in 1898, and voiturettes in 1899, all of which taxed the productive capacity of his factory. Adler undertook a contract to build a batch of motor tricycles for Cudell, and during a visit to Paris in 1899 was so instantly struck by Louis Renault’s new voiturette that he resolved to start building motorcars of his own.

The first Adler car appeared in 1900, installed with a single cylinder De Dion–Bouton engine and, unsurprisingly, closely resembled the Renault, as a face-to-face 4-seater with tiller steering. Kleyer soon became recognised as one of Germany’s established motor vehicle builders, assembling further cars using proprietary De Dion 2- & 4-cylinder engines from 4½ to 8HP rating, as well as the Adler factory’s own single and twin cylinder engines made to De Dion pattern.

With progression into motor vehicles, the company began to build motor cycles of 3, 3½ and 5HP from 1902, and managed to attract the talents of Austrian engineer Edmund Rumpler from Daimler. He joined the business as Technical Director, and produced for them the first German motor to have an engine and gearbox designed as a single unit. Adler manufactured this engine for use in its own automobiles, which were successfully driven in competition at many sporting events by Alfred Theves, and Erwin & Otto Kleyer (sons of the founder).

The Wright Brothers’ first successful flight in America turned Rumpler’s attention towards aviation and he left Adler in 1907 to pursue this new interest, becoming Germany’s first aircraft manufacturer by producing a copy of the Taube airplane designed by fellow Austrian Igo Etrich.

Production of motor cycles ended by 1910 while concentrating on automobile engines, which were rapidly developing with increased power from a 12HP twin to 24HP four-cylinder block for Adler’s larger cars, 1-litre motors for light cars and up to 9-litre capacity for commercial vehicles.

The intervention of the First World War redirected Adler’s manufacturing from civil applications, towards trucks for military use, field ambulances, and special engines, and it took a while after the Armistice for the domestic market business to recover.

The 1920s found Adler’s automotive products booming, and the company producing a significant range of vehicles from ‘standard’ model cars to luxury limousines and competition sports racers with 6- and 8-cylinder engines.

Into the 1930s, Adler developed into one of Germany’s leading and most prestigious automotive manufacturers and commanded up to 20% of the German motor car market.

With the onset of Fascist politics and Hitler assuming power in the country from 1933, former Adler Technical Director, aircraft and automobile designer Edmund Rumpler, was imprisoned simply because he was Jewish. His career was ruined and, though shortly released, he died in 1940 and the Nazis destroyed his records.

Adler ceased automobile production in 1939 as the outbreak of World War 2 changed social priorities. Adler production during World War 2 was mainly switched to the construction of military equipment, with the factories becoming the largest manufacturer of armoured tank chassis in Europe. Allied bombing in March 1944 specifically targeted the industrial area of Frankfurt, during which the Adler factory was practically destroyed, leaving little more than the shell of a few buildings. The Katzbach concentration camp field workhouse was subsequently erected on the site, with more than 1,600 prisoners compelled to work in its factory under SS supervision. Only two-thirds of the inmates survived to be liberated by American forces just one year later.

Like the Horch limousines, and due to the popularity of such vehicles with officers of the Wehrmacht, practically the entire available stock of Adler cars was ‘adopted’ by the military to be used for transporting top-brass on the various campaign fronts. Relatively few examples of these magnificent machines from either make survive today.

All that could be salvaged from the ruins of the factory site was taken to the town of Bruchköbel near Hanau, where Adler bicycles resumed assembly at the premises of a kitchen furniture factory.

Post-war typewriter production returned in 1946 with the ‘Little Adler Model-46’. Following a plan to resume car manufacture at the conclusion of the war, Adler began to produce automotive replacement parts and undertake repairs of motor vehicles, while developing a modern two-door sedan that was intended to be constructed at a rebuilt factory from the same site, situated on a street renamed Kleyer-Strasse in tribute to Adler’s founder. While the factory was reconstructed, the new prototype 1.2 litre, four-cylinder Trumpf model was inexplicably scrapped on orders of the senior management, and never saw production. This decision was never officially explained, and it became much conjectured that it was the result of a tacit agreement with another car manufacturer to avoid competition. A more likely reason however, may have been the weighty financial consideration and difficulty of re-establishing automotive construction, with poor projected sales prospects for relatively expensive and quality vehicles at such a time of post-war hardship.

Instead, Adler opted to manufacture motor cycles, which required a lower investment and could engage factory production fairly quickly. Motor cycles would probably have been considered an easier product to sell under the austere social environment of the day; a logical choice for the short term, though a lot of other German manufacturers had the same idea, and the market would certainly be competitive. Adler resumed production of motor cycles in 1949 with an M100cc two-stroke utility model, followed by a 125cc motor cycle and, subsequently, a 150cc machine. While many other motor cycle manufacturers were reviving old pre-war designs and basically taking up where they left off, the Adler machines were all built to new designs based on the latest ideas, since it was nearly 40 years since Adler had built its last motor cycle.

This time the company favoured its own two-stroke engine designs, fitted into soundly constructed frames, invariably with twin-down-tube geometry, telescopic forks and rear suspension systems, at a time when other makes were generally less well equipped.

Adler’s reputation for quality maintained increasing sales, and larger capacity models were added to the range: a 195cc two-stroke twin in 1951, and 247cc twin in 1952. Sales were further promoted by successful racing campaigns of the 250 twins in air-cooled and water-cooled versions. Victories were recorded by Beer, Falk, Lohmann, Luttenberger, Vogel and others, while other Adler models also competed in off-road events.

Just like many motor cycle producers across Europe in the mid-1950s, Adler began to experience their sales slipping away as the improving social situation found people with more disposable income, so a growing demand for cars was progressively replacing motor cycles. British, Italian and French motor cycle manufacturers were all facing exactly the same position as the German industry and, like many other builders, Adler sought economic refuge in an unlikely but fashionable alternative product: the scooter!

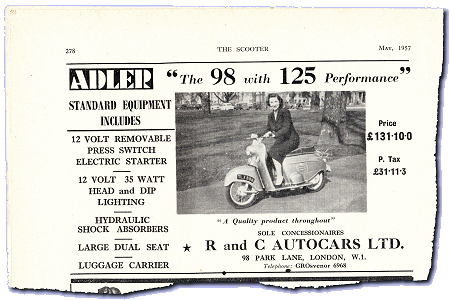

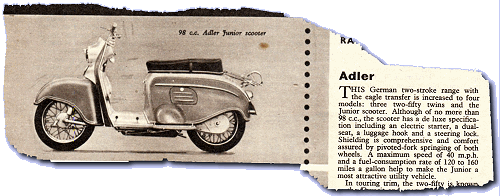

In 1955 Adler presented its new MR100 ‘Junior’ scooter, with 98cc fan-cooled 2-stroke single-cylinder engine, 50 × 50mm bore & stroke, rated at 3.75HP, with three-speed foot changed gears.

The van arrives with our test machine, and this certainly looks like a very big and heavily constructed scooter! Is this really just 98cc? We recruit some assistance with the unloading, since this isn’t the usual sort of small capacity lightweight anyone might be expecting to manhandle on their own. Down to ground level, we roll ‘Junior’ straight onto the scales, 7 stone front + 10 stone rear = 17 stone (108kg), which is quite a substantial load for a low power 98 to be hauling about. There’s certainly no economy of materials going on with this bike!

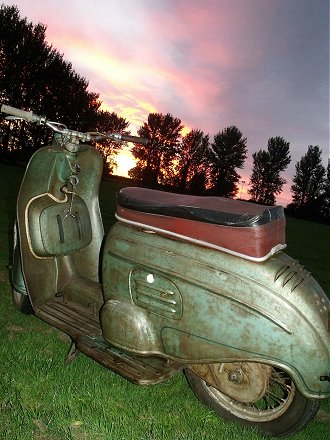

The body shell was originally finished in light blue-green metallic with dark blue pinstripe but, with the passage of time, has faded to a pale green and surface rusted patina, now seemingly preserved under a lacquer seal.

Adler’s nacelle carries a Hella headlamp and a big & showy aluminium-faced Noris horn. The rear, however, mounts a Lucas 529 taillight, which would have been the original fitment for the UK, since a matching Hella rear lens for the continental market wouldn’t have had a clear port to illuminate the rear number plate as required in the UK. A British market lamp would probably have been fitted at point of sale. Adler Junior scooters were imported and listed in the UK from 1956, so this Lucas lamp would be considered original equipment in this country.

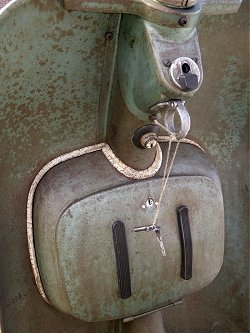

There’s a lockable toolbox inside the front apron, and a cast alloy bag catch fitted below the steering stem lock. An aluminium cast central handlebar clamp tops the steering stem, which goes down through the body-shell headstock to a substantially-constructed Earles pattern front suspension set. Spoked wheels are shod with 3.00×14 front and 3.25×14 rear tyres. A pressed steel guard fully encases the chain final drive, so this is a scooter built with practical intentions of use under all weather conditions.

The rear footplates stick out from the body-shell almost like a pair of wings, or the tail plane fins of a missile, though Junior’s incongruous and bulbous body panels are hardly sleek or dynamic to match this delusion—less like a jet, but more like a cargo truck! The wide and protruding rear footplates are one of Junior’s most striking features in more ways than one—not only as a visual oddity, but as an ever present hazard when navigating the machine, or when walking by the bike, since you know they’re just waiting for some absent moment when you drop your guard, to bang your ankles painfully or skin your shins.

Sparking plug service is accessed through the front engine inspection cover, which is also where you’ll find the petrol tap switch hiding in the gloom. Turn for off–on–reserve. There’s a choke trigger under the right-hand cluster, then just putting the key straight in the lock engages an ignition lamp in the speedometer. No use looking round for a kick-start, there isn’t one … the only starting method on this Adler Junior is electric starting, and how ambitious was that for the mid 1950s? Push the key in to activate the dynastart motor, which turns the engine with a steady bloop, bloop, bloop … a couple of half-hearted coughs … then the motor rumbles into life with a low burble.

The engine runs with a flat exhaust note, producing a deep-frequency vibration, and generally gives the impression of a low compression and low revving motor. Twin exhaust silencers are slung under the footboards like a pair of drop torpedoes, and smoke just seems to emanate from every direction beneath the bike, some rising in clouds around us, while other heavily oil-laden fumes roll away ominously at ground level like some volcanic pyroclastic flow … probably time we got out of here…

Pulling in the clutch we find the gear-change heavy, stiff and notchy; it really only seems to understand the firm application of a heavy boot to its heel-and-toe, rocking-pedal change. Neutral lies at bottom of the box, with 3 × heel-back selection to change up, then forward toe (more like stamp down with the ball of your foot) to shift back down the cogs again. Changing up from first to second, you sometimes find you’ve randomly shifted straight through two gears and into third.

Not really what you’d normally call acceleration as such, the torquey ‘building up’ of speed is lumbering and ponderous and, coupled with the industrial gear-change, very much imparts a crude and truck-like impression. Exhaust smoke billows liberally from seemingly everywhere underneath the footboard wings as we bumble up the road, giving the impression of some crippled bomber struggling back across the channel from the Battle of Britain. The rider of our pace bike looks incredulously amused and laughing hysterically at our plight as our Adler leaves a swirling fog-like trail of haze in its wake.

Settling to a happy cruising speed indicating 30mph (pace bike also showing 30), we’re beginning to wonder quite what kind of fuel is actually in the tank? Our only hope is that the oily vapours might abate as the engine gets hotter and settles down. By the time we’re approaching the three-mile marker, the worst of the oil smog has begun to clear from our smoky old bonfeuerwehrwägen, so, presuming the motor might now be worked up to temperature, we crouch into the cockpit and go for our best on-flat paced run—speedometer indicated 36–37mph, which the pace bike clocked at 35. Downhill run indicated 40mph, and pace bike also confirmed it at 40.

Adler’s speed for the 98cc Junior was given as 65km/h or 40mph, so we considered our test results reasonably representative for a nearly 60-year old machine. As expected and due to the bike’s weight, the low compression motor faded dramatically on the uphill climb and obviously wasn’t going to complete the ascent in top (third), but by the time resistance from the reluctant gear-change had been overcome while the speed continued to fall away, and we’d finally managed to crunch it back into second, Junior only managed to crest the brow at a miserable 15mph.

Main lighting is switched by turning the ignition key, leaving the left-hand cluster simply arranged with just the horn button and a beam–dip switch. It’s very much basic controls only, there’s nothing fancy here, purely function and not much luxury in the 1950s.

The petrol tank filler is found beneath the enormous Denfeld dual seat, which at 25 inches might even seem long enough for a whole family and the dog!

We don’t know whether Adler actually fitted a centre-stand; our test bike doesn’t have one, but there’s a lug under the frame that looks as if it might have been intended for a stand, though it doesn’t show much indication of ever being used. Our Adler has a prop stand tucked towards the back under the left-hand footplate, but this proves really difficult (practically impossible) to tag down with your foot, so you invariably end up grovelling under the bike to try and find the wretched thing, which seems rather unlikely, so we’re not entirely convinced whether this was an original fitting or not.

The half-width hub front brake was weak, the half-width hub rear heel-back brake was very poor, and you could sometimes find yourself lifting off the saddle if you were really wanting to stop at a junction. Considering the heavy weight of this scooter, braking really wasn’t up to the capability we’d be expecting of Adler’s build quality reputation, so there’s some feeling the lack of performance might be put down to the drums needing an overdue service.

Intrigued as to what might actually be lurking inside the voluminous rear body section, we set about raising Adler’s shell to have a look at the mechanics beneath. This task isn’t anything like simply removing the side-panels from a comparable Italian scooter, since Adler’s body is basically a one-piece shell with a few small inspection ports. Nor does it hinge back like the DKW Hobby body-shell. With the Adler you have to remove several bolts, and disconnect wiring though the left-hand porthole, then lift the entire body-shell completely off the bike-and it’s very heavy! This really isn’t a one-man job, and you most certainly wouldn’t want to be struggling with this task by the roadside.

Beneath the exoskeleton, the engineering’s impression is substantial and primitive. The motor looks like a proper quality industrial job with its cast alloy fan-cooling shroud. There are two batteries (one each side for balance maybe) to support the electric start, but that rear suspension swing-arm arrangement doesn’t look very high-tech.

Adler Junior looks like a truck, weighs like a truck, rides like a truck, performs like a truck, and seems to be made like a truck—conclusion, it’s a truck!

The 12-Volt dynastart equipment set must be a significant contribution towards making this about the biggest and heaviest under-100cc scooter that anyone has ever built, but what a bold decision for Adler to have made by producing their scooter without any back-up starting means as far back as 1955, and to rely solely on electric starting!

Our lasting impression was that the 98 Junior was very much overweight and underpowered. The 98cc Junior scooter was joined by a 125cc Junior Sport model in 1956, of 54 × 54mm bore and rated at a healthier 7HP for, presumably, a much better performance.

Adler’s new scooters were probably only off-setting falling sales of its motor cycles, but weren’t really making the trading conditions much different at a tough time for the market. In 1956, backed by the Deutsche Bank, Max Grundig managed to acquire a majority shareholding of the struggling TWN company (Triumph Werke Nürnberg), primarily to secure its established presence in the office machinery market, and TWN moped, scooter and motor cycle manufacture was summarily concluded as its new owner had no concern for this sector. Radio and television manufacturer Grundig also bought out Adler towards the end of 1957, again solely to acquire its typewriter business. It merged the two office equipment interests as Triumpf–Adler at the Adler site in Frankfurt in 1957.

The last Adler motor cycle and scooter components were built out and cleared in 1958, the business continuing with office equipment production. Adler Junior imports to the UK were officially completed in June 1958 and the scooter was de-listed.

The US Corporation Litton Industries purchased Triumph–Adler from Grundig in January 1969, adding the business to its office equipment portfolio. Volkswagen acquired a 55% controlling stake of the business in March 1979. The Italian typewriter and computer manufacturer Olivetti purchased Triumph–Adler and (US) Royal Typewriter from Volkswagen in April 1986. In 2003, Japanese Corporation Kyocera Mita acquired a 25% interest in TA Triumph–Adler to form a strategic alliance. This stake was increased to nearly 30% the following year.

While many moped, scooter and motor cycle manufacturers from the 1950s are no longer around today; TA Triumph–Adler still continues a very healthy business in office equipment manufacturing.

Next—Our world series has taken us right round the globe, and now it seems we might be right back where we started, in France. Our story begins in 1899 with the business of Chavanet, Gros, Pichard & Cie and is likely to end up in the road-test of some obscure moped you’ve probably never heard of before.

Let’s hope we might get lucky with this Cloverleaf.

This article appeared in the

April 2014 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2014

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Our ‘Number three oddball feature’ was certainly an oddity this time. An Adler Junior 98cc scooter isn’t something you bump into too often!

We’d had our eyes on this machine for a while as owner David Whatling at Horham had been tinkering with it for a few years, finally getting the bike to practical operating order by summer of 2013. We processed recovery of the original registration serial from a records copy, and with the bike now all sorted, managed to secure it for road test & photo shoot in September 2013. Completing the article aspects, the Junior also went on for display on the EACC/IceniCAM stand at Copdock Show in early October, before returning with its owner in exchange for another machine to be featured in another future article-the conveyer belt keeps rolling…

Falling within our general ‘under 100cc’ brief, the Adler was certainly a must-do. We can’t think we’ve ever actually seen another and probably don’t expect to, so this was an opportunity we had to seize. The Adler also offered the prospect of a double-whammy publication as the Vintage Motor Scooter Club Magazine is also expected to present a licensed version of the feature too.

Apart from the huge physical size and considerable weight of the 98cc Junior, the greatest surprise was the motor being solely reliant on electric starting! This was a startlingly bold move for Adler to introduce so far back in 1955 and undoubtedly would have represented a major marketing feature that few other manufacturers of the time could boast in reply.

When compared to the miniature electric starter systems of today, the primitive electric dyna-starting system was big, complicated and an expensive addition, and starkly illustrates what a long way this technology has progressed in sixty years-but in 1955, Adler’s electric starting feature was positively cutting-edge!

In covering the research for drafting the text, it became obvious that Adler’s founder, Heinrich Kleyer was an instinctive entrepreneur who recognised good ideas and adopted them to his great success. The Adler company reveals a fascinating history, with connections to Edmund Rumpler as founder of Germany’s first aircraft builder, to Adler’s automotive heyday in the ’20s and ’30s, before World War 2 resulted in destruction of everything, as wars often do.

The 98 Junior scooter came towards the very end of Adler’s renewed post-war motoring era, but at the start of a new future beyond vehicles, and the business that Heinrich Kleyer started back in 1880 is technically still around today, though in a somewhat evolved corporate form.

Production costs were reasonably moderate, totalling around £30 in diesel fuel, and the article was sponsored by a donation from Colin Clover of our own Suffolk Section EACC.