Formal introductions really won’t be necessary, since it should be fairly obvious where this feature is going...

At the age of 40, Soichiro Honda founded the Honda Technical Research Institute in October 1946 and with a staff of 12 men working in 16m² shack, they built and sold improvised cyclemotors from a supply of 500 war surplus Tohatsu 50cc radio generator engines.

1947 Honda Model-A

When the engines ran out, Honda started building his own copy of the Tohatsu engine and began selling these as attachment kits for customers to fit to their bicycles. This was the Honda model-A, and often known as the ‘Bata–Bata’ from the sound that it made.

The Honda Motor Co Ltd was established in 1948 and built its first complete motor cycle in 1949, the two-stroke model-D ‘Dream’. Honda’s first four-stroke was the 1951 146cc type-E.

1952 introduced the original Honda Cub-F as a clip-on bicycle engine but, except for the name, this model was completely unrelated to what would follow...

In 1956, Soichiro Honda with his business financier Takeo Fujisawa, toured Germany and visited manufacturers’ showrooms to study the popularity of mopeds and lightweight motor cycles. Fujisawa became convinced there were opportunities for a new type of 50cc utility ‘motor cycle for everyman’, with both urban and rural appeal, in established societies or for developing countries.

The new machine needed to be technically simple so it could be maintained practically anywhere without the need for complicated support. It needed to be quiet, reliable, and simple to use, with a covering to hide the engine, tidy the cables and wiring. Then Takeo claimed he could sell such a machine in significant numbers.

Another of Fujisawa’s requests was that it could be ridden with just one hand, while carrying a tray of soba noodles—then every noodle shop in Japan would want one for deliveries!

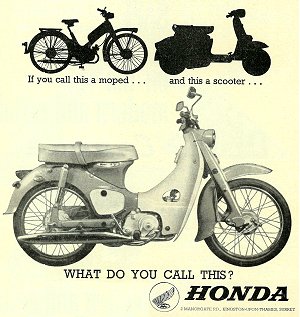

The established scooter concept nearly fitted the bill, but the small wheels would be awkward on poorly maintained roads or unmade tracks, and the body shape presented maintenance difficulties.

Since Honda was a large company with ambitions to further expand, it needed a mass appeal product that could be produced on an enormous scale. The design would need to be thoroughly sorted before volume manufacturing, since it could be far too costly trying to resolve problems once production had begun.

Once Honda adopted the design ideals, he began developing the machine upon his return to Japan, and presented a mock-up the following year, to which Fujisawa predicted sales of 350,000 per annum for this single machine.

The significance of this figure only comes into scale when one considers that the entire two-wheeler market by all manufacturers in Japan at this time was only 230,000 per annum, so this was a most ambitious and dramatic proposal.

In the economic disorder of post-war Japan, home market sales alone would not be expected to absorb such production volumes, so the plan would demand building and export on a completely new scale.

The proposed enterprise required a huge leap of faith!

Based upon a model of the Volkswagen Beetle production line in Wolfsburg, Germany, Honda built a new ¥10 billion factory at Suzuka to manufacture a planned 30,000 machines per month on single shift, and up to 50,000 machines per month operating on two-shifts.

Up to the commissioning of the new plant, Honda’s top models had only sold 2–3,000 per month, so this really was a quantum jump, and many observed that the investment gamble was too risky an expenditure ... but what you need is belief ...

As production engaged, Honda revived an earlier name for the model, but added a prefix, and so the all—new lightweight machine came to be titled as ‘Super Cub’.

The Honda Super Cub was first presented in 1958, though initial home market sales proved quite poor, mainly due to a Japanese recession. Some three months after the launch, customer complaints arose about slipping clutches, and Honda staff and factory workers gave up their holidays to personally visit all individual customers and repair the affected machines, so the C100’s début was by no means a golden arrival.

To secure sales into the giant markets of the USA, Honda needed to provide the necessary distribution, service, and spare parts support, to which end it established the American Honda Motor Company in 1959. When the Super Cub began exports to the USA, its title was simply reduced to Honda 50 (and later called the Honda Passport), since the Piper Aircraft Co had previously registered the ‘Super Cub’ name for one of its planes.

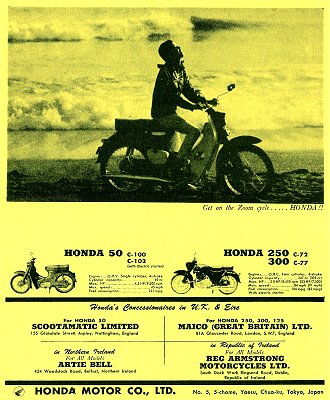

November 1960 advert showing

Scootamatic as Honda agents

When the Suzuka factory was completed in 1960, it became the largest motor cycle factory in the world and a model towards Honda’s mass production facilities of the future. The economies of scale achieved at Suzuka when the plant could be run at full capacity, would cut 18% from the cost of producing each Super Cub but, in the short term, Honda faced excess stock problems as all the export sales and distribution networks were not yet in place to market the volumes the giant factory could now produce.

Edward Turner (notable as designer of the Ariel Square Four and Triumph Twin, now Managing Director of the BSA–Triumph Group) visited Japan in September 1960 to study their developing motor cycle industry, and thought investments on the scale of the Suzuka plant ‘extremely risky’, since he considered the US motor cycle market was already saturated.

The first British public’s first encounter with a Honda motor cycle occurred on the Scootamatic stand at the Earls Court Show in November 1960, when samples were displayed along with further selections from Auto-VAP, Capri, Como, Laverda, Vélo-VAP, and Elswick–Hopper’s Lynx prototypes. Formed by the management of Elswick–Hopper, Scootamatic was a new company specifically set up to handle sales of imported mopeds and scooters, though they actually declined the Honda, thinking it wouldn’t sell.

Honda secured its first European sales network in Germany in 1961, then Belgium in 1962.

Having failed to arrange UK market business though the Scootamatic agency, Honda followed the same approach as for the US, to establish its own distribution company as Honda (UK) Ltd, Power Road, Chiswick, London W4. Initial imports began with just four listed models from November 1962, C100 Cub @ £82-19s, C102 electric-start Cub @ £101-17s, C110 Sport 50 @ £109-19s, and CR110 production racer at a staggering £399.

As in the US, it also transpired the ‘Super Cub’ name could not be applied in Britain either, since Triumph Motorcycles already held precedence to the title with its Tiger Cub model, so UK market machines were simply badged as Honda 50.

While the CR110 was certainly an impressive miniature competition machine, its listing was little more than a promotional presence to promote Honda’s technical abilities. It was the robust 50cc C100 step-through scooterette that proved the vehicle which really established Honda’s public reputation for small four-strokes wherever it appeared. This enduring little bike became their leading model in the UK after commencement of sales for the 1963 season, though with footrests, kick-start and semi-automatic foot-change motor, this machine wouldn’t comply with moped criteria, and was actually classified as a motor cycle.

Registered FRT 578C in 1965, our first Honda C100 has been left for us, all locked up, with the keys posted through the door in an envelope.

There’s a steering lock at the bottom fork yoke, which requires its own key, separate from the ignition switch, so we’re presuming one (or both) of the locks might have been changed at some time, since we would ordinarily expect the original locks to match.

Through an access port in the right hand leg-shield, the Kei Hin carb has a vertical venturi with a horizontal float chamber topped by a fuel off–on–reserve switch to the right and choke switch accessed though a leg-shield port to the left. The choke operates a shutter through 90 degrees, which should make the fuel rich enough for any cold conditions. There is also a flood button on the top of the float chamber, but conditions would probably be inconceivable that you may ever need to use this.

Engine specification is four-stroke push-rod motor of wholly iron cast top-end components, 40mm stroke × 39mm bore with 8.5:1 compression ratio and rated at 4.5bhp @ 9,500rpm.

Typically of the time, the traditional location of the ignition key switch is on the left hand side panel. It’s been a while since manufacturers put them there, but that’s how they used to do it in the old days.

Ignition switch is three position: off–on–lights, thereafter a left handlebar switch works beam–dip, horn button below (which doesn’t seem to work on this bike), and indicators L–off–R by a switch on the right bar.

When you turn on the ignition, a small red light glows on the top of the headlamp. Possibly riders might have taken this for an ignition indicator at the time, since a neutral indicator lamp would have been rather a novelty back in these days.

Wheel/tyre sizes are 2.25–17, still a common specification today, but practically unknown when the C100 first appeared.

The semi-automatic gear change is located on the left side, operated by heel-and-toe rocking pedal, back for first, forward through neutral into second, then down again for third. Selection throughout was light and positive, though these semi-automatic ‘crunch’ gearboxes can be clumsy and dramatic if the bike is ridden aggressively. The secret is to change up early for a smooth shift, and change down late to avoid the clunk. The ‘crunch’ box doesn’t respond well to frantic riding, will become noisy in operation and lurch the bike about if pushed hard.

A light buckle in the rear wheel was noticeable right from pulling off, the sensation of which was probably compounded by the rear wheel set out of line (adjustment, which we noticed on examination upon our return), and the steering tending to wander somewhat from over tight head bearings.

By the time the bike was getting up to speed , our C100 became a little ‘ambitious’ in terms of the amount of carriageway it wanted to occupy—still, we battled on with our test, indicating a best on flat of 41, though our pace bike disputed this as optimistic, actual 37–38mph.

Our downhill run bravely weaved to an indicated 45, which was towards the end of the Nippon Seiki speedo’s marked area for max speed in top gear, but again our pace bike only confirmed a lower 41mph.

The motor gave a strong account against the uphill climb, and crested the rise at an indicated 30, which the pace bike read at 29, so a good showing in this section.

Throughout the test, it was particularly noticeable how lots of noise comes back at the rider from the air intake. An interesting comparison to later developments, where this early paper element filter certainly made nowhere near the efficient job of suppressing induction roar as subsequent C50 models do.

The foot-brake pedal on the right was particularly strong in operation and well capable of locking the back wheel. This would normally be the rider’s brake of choice, since application of the front brake causes the fork to rear up on the leading link suspension; definitely not the sort of situation you want to be involved in when the road surface might be wet or slippery.

Driven direct from a generator coil, the C100 headlamp is not supported by the battery, and only operates when the engine is running. Performance of this headlamp was nothing short of comical, and certainly a practical contender for the ‘Dimness Award’ that has been so fiercely fought for between so many makes of old autocycles over the years!

Stopping on a dark country lane, all the accompanying bikes were encouraged to stop their engines and turn off their lights, so the C100 could display its illumination in singular glory. At tick-over, the headlamp appeared as little more than a dull candle, then progressively raising revs to a snarling crescendo, the glow gradually increased to a dull glimmer that just about trickled to the front number plate and mudguard.

Everyone fell about laughing, as no light whatsoever could be detected on the road.

Clumsy steering and a light buckle in the rear wheel made our first bike a somewhat ‘wandering’ ride. The electrical set didn’t seem up to par, neither were we wholly convinced that the performance was quite up to the mark. Speculating on whether or not our first C100 example might have been totally representative of the breed, we went and got another one...

Registered AVL 231C in 1965, our second Honda C100 looks to have experienced extensive restoration, and is identified on the serial plate as type C100K.

All pre-flight observations proved exactly the same as our first machine, and a turn of the key in the ignition was again greeted by a welcoming glow from the red neutral light.

A couple of gentle swings on the kick-start encourage the motor to burble into life, then ease off the choke until the engine runs clean. Blips on the throttle are responded to by some draw from the air intake, so it looks as if induction roar is certainly a common characteristic of these models.

Rocking the gear-change pedal back for first is responded to by the usual clunk and lurch as a good indication the gear has engaged. Acceleration is steady, though unspectacular, as you progress up through the gears, interspersed with noisy induction bursts from the air-box as the throttle is opened under load, accompanied by a low growl from the exhaust.

The old C100 certainly has a distinctive tone of its own and can easily be distinguished from later models.

Leave the twist-grip open, and the revs seem to keep climbing to what might have been unimaginable levels in the 1960s for a single-cylinder push-rod engine with an iron top-end. Iron barrel, iron head, and iron rocker box were not of dissimilar construction to many other utility motor cycle engines of the time, but somehow the Honda seemed to rev higher and smoother than anything else—how did they manage that?

Onto the main straight, we can only just about manage to work up to 30 against a strong headwind, with the throttle wide open under load, and a noisy induction roar resonating from the air-box.

Turning into the lane toward the end of the straight, the wind swings round behind us, now with a hot motor from its earlier exertions, and our C100 whirring away beneath us like a busy sewing machine, we build up to a paced peak of 41–42 on the flat.

With Honda’s speedometer graduated by ‘speed-in-gear’ bands and indicating up to 45 in top, we’re getting hopeful of reaching this target as Iron Horse gallops into the downhill run with our pacer tracking close in our hoof-prints. With the speedo needle toward the end of our dial through the dip, our shadow clocked best downhill at 48mph as we charged into the following climb. With speed falling away up the ascent, the pace bike tracked us down to 25 before cresting the rise, still in top gear. So, though our second test bike was faster downhill, it proved slower going uphill! Exactly the same models—but very different in the way that they go.

This second bike also had a noticeably stiffer gear-change than the first.

On this bike we were also reminded to be cautious of those fixed rear footrests which don’t fold up, because if you kick the starter with ball of your foot, then your heel can painfully clip the rear footrest ... and they occasionally bang your shims while navigating the garage.

Both bikes would naturally settle to a leisurely cruising speed around 30mph, which is conveniently appropriate for urban running.

Our second test bike did exhibit appreciably better handling manners, and slightly more effective illumination than the first, but still nothing that anyone might boldly describe as good lighting by any standards today.

Honda secured further European distribution by establishing export and sales into France in 1964.

Ironically, after declining the licence to import and distribute Honda models into the UK at Scootamatic, Eric Sulley went on to become Head of Sales and Marketing at Honda GB.

Honda built the C100 Cub from 1958–1967 and, though the original Iron Horse was led out to pasture, it sired many generations of successive models. C50, C70, and C90 Cubs took up the reins from 1966, and its derived spirit still continues in production in various manufacturing plants across the world today.

The numbers say it all:

Morris Minor—1.3 million

Austin Mini—5.4 million

VW Beetle—19 million

Having been in continuous manufacture since 1958, Honda Cub production exceeded 60 million in 2008.

The Honda ‘Super Cub’ is the world’s most successful vehicle ... and it’s still going ...

Next—Our third ‘oddball’ feature has presented some unusual machines on occasion, and this time we’re heading to Italy for other obscure machines that few will probably know. Established before the last war, one of these companies is still around, but seems to continue under a low profile because of the nature of its ‘specialist’ products. Its name has probably come up a couple of times in some of our previous articles, but only as incidental background, so may anyone have noticed?

Back in October 2008 we presented a feature on Trade Carrier Autocycles. Well this feature covers a sort of later equivalent that never really caught on in this country, but became quite popular across the Continent. Some clue is in the initials and translation of Priemoné Transporto = ‘vehicle intended for the carriage of freight’, but in our case—we’re talking mopeds!

This article appeared in the

October 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2013

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Iron Horse was one of those articles that just never quite seemed to make the cut ... would we ever get it out?

The feature actually started in April 2011 with the road-test and photoshoot on Neil Bowen’s C100 from Felixstowe, shortly before the bike was sold on after receiving some work to improve aspects arising from the road-test.

Our second machine came courtesy of Keith Miles at Great Cornard in Essex in June 2012. This bike generally went a little better (apart from stiffer gear selection), but strangely found less steam uphill. It’s sometimes puzzling why different bikes of the same model can vary so much, but does support a strong argument for our sometimes testing more than one of each type.

There was hope to include a third machine in a different colour (red), but this test never materialised, which probably delayed the feature at the crucial time and gave Folders the publication edge. The photoset might have been more balanced by presenting pictures of a C100 in a different colour, and we would have liked to do so, but this was not to be. We dallied with the possibility of another, fouth C100 in red, but again this failed to materialise so, despairing of trying after any more red bikes, the time came to just settle for two blue.

The developing Iron Horse article had a 1-in-3 chance of getting to publication for the October 2012 edition, but was beaten to the cut by the Folders feature instead. Another article called Moped Army was also in the running at the time, but that has completely disappeared back into the archives and we’ve absolutely no idea when that might surface again!

As it worked out, at 24 pages, IceniCAM 27 proved a pretty big magazine and there was even a question at one stage as to whether the Iron Horse article might get dropped altogether, but made it in the end, to create another bumper edition.

Production costs involved the usual diesel fuel (about £30) to collect and return our second bike from Essex.

The text drafting for all three feature articles for edition 27 certainly ran right up to the wire. With so much other stuff going on since last edition, 26, hardly any writing on No 27 started to even happen until Wednesday 28th August, and with an editorial deadline of Monday 2nd September, Danny finally sat down to tackle the task at the last minute—which then involved five continuous days and two overnight sessions of solid writing to eventually complete the final text at 7.30pm on Sunday 1st September.

Certainly there were several text blocks that had already been worked up to varying degrees, so it wasn’t all starting from a blank page, but there really was an enormous amount to do in a very short space of time.

The Yamaha QT and Dax text sections had largely been completed in earlier sessions, but much of the rest for all three features only existed as road-test and basic impression notes, so opening up files with no more than minor content probably isn’t ideal with time pressures on and the clock ticking loudly.

The archived Iron Horse feature proved to be no more than basic road-test notes when the file was finally opened to commence work on Saturday morning 31st August so, starting with little more than a structure concept, the whole article was researched and completed in just two days—that’s what you call really pulling out all the stops!