We pick up our story on Monday 10th June 1940 - Italy has declared war on Great Britain and France, and Italian troops have crossed the border into France.

31-year-old Rosario Di Blasi had long held passions for flying and technical engineering and this same year completed development of his Ruler for Carteggiarre, a slide rule type tool to perform calculations for aerial navigation.

Now, as a pilot in the Italian Air Force, he would be going to war flying Savoia-Marchetti SM79 Sparviero (Sparrowhawk) triple-engined bombers over the skies of North Africa, Malta, and the western Mediterranean.

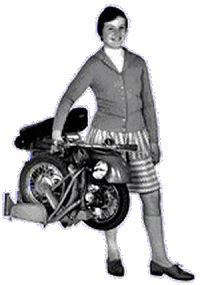

Prototype Folding Di Blasi scooter

In 1942, the then Major Di Blasi published an article titled "Operational Diagram of a Rotary Engine" in the Italian Ministry of Aeronautics magazine Rivista Aeronautica, to present the functional theory of a rotary motor. In February 1943, the same article was re-published in the German magazine Deutsche Luftwacht Luftwissen, and the principle subsequently developed to be more commonly known as the Wankel engine.

Immediately after the war we find Rosario living in Rome and owning the valuable asset of a bicycle for transport, which for fear of theft he was compelled to carry up and down the flights of stairs to his eighth-floor flat since the buildings elevator was too narrow to contain the cycle - and this was what prompted his idea of a folding bicycle that would be easier to transport.

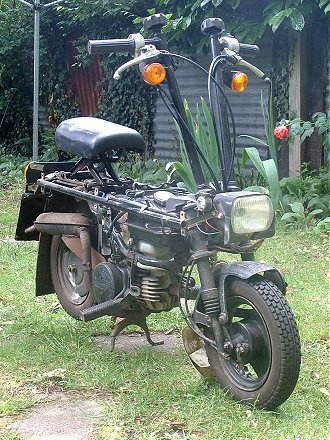

DIBLA-7 at the 1968 Turin Auto Show

By the end of the 1940s Rosario was discharged from Air Force Service and began an agricultural business back in his birth-town near Syracuse, Sicily.

As an interest, he began development of his idea for a folding cycle, but now to be equipped with a small engine in similar manner to the latest and popular Vespa and Lambretta scooters.

From 1952 to 1956 he created a developing series of various folding scooter prototype models with imaginative solutions to compact the frame.

The project and ideas largely became mothballed until revival in the late 1960s when the first DIBLA-7 patented folding tricycle prototype was shown at the 1968 Turin Auto Show, powered by a Zanetti-Bologna engine and fuelled by a Dutch Encarwi diaphragm carburettor.

The DIBLA-7 tricycle did not progress to production and it was 1973 before further developments of folding-frame concepts were exhibited at the Milan Motorcycle & Cycle Show. Protected by international patents on the quadrilateral hinged-frame design, this time the models comprised an Avia collapsible bicycle with newly-invented folding pedal arrangement, and an R2 compactable moped.

While the timing was probably good from an interest and publicity point-of-view, due to presentation at a time of international oil shortages and the subsequent topicality of economical transport, it wasn't really much value for generating immediate sales - since once again, the models were only prototypes!

From a manufacturing unit established at Vizzini in Catania province, Sicily, production proper only finally began in 1974 with the R2 "Paperino" folding mini-scooter propelled by a Morini Franco single-speed automatic engine.

In 1979 the R2 was replaced by an R7 model featuring a variator transmission engine of Di Blasi design based upon Motobécane elements. Variable gear transmission comprised an essential element of extracting practical performance from the 50cc engine in combination with the technical limitations of tiny wheels, so the R7 model was truly a quantum development leap forward.

Di Blasi folding bicycles also continued to evolve, the R20 model replacing the original Avia in 1980.

Our 1982 model R7WT Di Blasi arrives tucked into the boot space of a small hatchback, and neither does it fill this meagre trunk; with a folded cubic space of 1 foot wide by 2 feet high by 3 feet long, there's still enough room for a few bags of shopping!

The fabricated steel petrol tank forms a structural member of the frame, and there's a certain technique to most easily extract the 60 pound (4¼ stone or 27 kilogrammes) bike over the rear sill; hold by the rear of the fuel tank with one hand and fork stanchion with the other, then securely lift out without any handling issues.

OK, now the compacted cycle is standing on the floor and looking like a motor cycle that's just come out of the crusher!

To expand, just lift by the seat and the frame joints all fold out at the various pivots, until there's a click when a spring-loaded latch locks into position under the sprung mattress saddle. The handlebar set folds upward across a 45° arc, and locks on the headset with another click latch. Fold down the footrests and you're ready to go! For an accomplished Di Blasi handler, the folded to ready-for-use operation can be completed within just 5 seconds - remarkable!

Starting ... There's the usual obvious stuff: pull on the petrol tap, check the kill switch to on, click down the choke on the Dell'orto SHA12/14, which will snap off once the throttle is fully opened ... but one more little trick or you'll surely be stopping up the road. Since Di Blasi is designed to be transported in a vehicle, you wouldn't want to be overwhelmed by fumes from petrol sloshing around in the tank while you're driving your car or van, so the tank breather vent is sealed with a screw valve for transportation. Forget to release this vent and the tank will vacuum along the road, fuel flow will very shortly cease, and you'll be embarrassingly stopped in the gutter.

The motor has a variator set mounted on the crankshaft journal, with a spring loaded jockey pulley to accommodate variation in V-belt tension as the moving cone activates gearing ratio change. The variator set also acts as a clutch as the V-belt idles between the bottom of the cones at tick-over, then engages as rising revs drive the moving cone inward. This sort of system can be tough work for a belt, and the manufacturer recommends replacement every 1,000 miles.

Final drive is by chain from a sprocket on the back of the pulley to a plastic rear sprocket - yes, the sprocket really is plastic, presumably intended to run clean and dry for handling without mess, it's a fairly large sprocket so weight is probably also a consideration, maybe low-noise, possibly cheapness? Speculation behind the reasoning for a plastic sprocket is almost infinite, but may not be particularly convincing for durability in comparison to steel. A fibreglass moulded belt-guard covers the primary transmission, and a multitude of engineering questionables, but isn't going to have any effect on suppressing any noise that all the various thrashing components are likely to produce.

The rear swing-arm connects to the frame by two undamped spring suspension units, while the front end sports a miniature set of undamped telescopic forks with just 1½ inches of travel.

The alloy wheels are cast by Bernardi, size 8×1.75, and wearing 12½×2¼ (62-203) tyres, though we're informed there seem to be variations within the R7WT denomination where some models have plastic wheels. The 80mm brakes are bound to stop well by the dynamics of small wheel physics, but with wheels this small, front braking can easily become a serious issue as over application may readily lock the wheel and convert your ride down the road to an A&E visit at your local hospital. The manufacturer recommends only 'judicious use of the front brake', and you don't want to find this out the hard way!

Lights comprise a single beam headlamp switched from the left handlebar, with a little blue button tucked underneath to make the horn buzz.

The somewhat delicate kick-start (don't kick this too hard otherwise it'll bend or break), works by an open gear quadrant onto a pinion on the main journal behind the variator. It's frail, crude and noisy, but simple, and should continue to do the job as long as you treat it carefully.

Since Di Blasi has no option to pedal assist, just open the throttle and let the belt take the strain as the clutching cone feeds in. Take-off proves better than expected, but first impression of the edgy steering and jelly-like handling will instantly convince any rider there won't be too much hand signalling going on. Barely up to 20mph along the road and you're very aware of a cacophony of transmission noise, accompanied by squeaking and creaking from the undamped rear suspension units as you bounce over a few bumps. The tuneless orchestral accompaniment really makes you want to stop and administer a smear of grease and drop of oil to the tortured dry parts, but hey-ho, we must press on...

There's a little acclimatising, but once you've adapted to both hands gripping firmly to keep the steering pointed where you want to go, the bike rides fairly typically for a small-wheeler, and after a couple of pace checks to confirm the 40mph Huret is indicating around 5mph fast at indicated 20 and 30, we're soon pressing along our series of flat runs to see what we might coax out of it. Despite isolastic rubber mountings on the engine, this still managed to transmit quite a lot of vibration through the seat, and the footrests, and the handlebars. Upwards of 20mph and you are going to be feeling these vibes.

The pace bike clocked our best flat run at 32mph with a light tailwind in upright position, and it doesn't feel as if you could safely crouch on one of these - and live to tell the tale! The downhill run glimpsed the Huret needle beyond the 40mph end marker, while our astonished pacer read this off at 37mph. The following uphill charge faded to 22 by our pacer's marking. Being devoid of pedals and with no prospect for the rider to assist, Di Blasi pulled up the incline respectably enough on its own, thanks to its variator transmission, to convince it was quite capable of the task.

In common with many of its small-wheel brethren, handling was nervous, twitchy, and jelly like - all at the same time. Just like the manufacturer recommends, you really don't want to be using that front brake much, which is probably mostly intended for Ministry test qualification requiring two independent braking systems. The rear stoplight operates from both brake levers. Neither do you want to be doing too much signalling either, since you just know that given the opportunity, Di Blasi will be in the hedgerow faster than a fly-tipper's pick-up truck.

Di Blasi is equipped with a proper miniature centre stand, so proudly and smartly snaps to attention when you want to park it up.

The 40mph Huret speedo attached to the right-hand handlebar stem indicated pretty much 5mph fast at all speeds right throughout the test.

Lights at both ends proved unspectacular, but probably adequate enough for the lowly speeds any sane rider might care to bumble along on one of these in the dark. No, on second thoughts you'd probably have to be completely insane to ride one of these in the dark, there's a clear and present danger some motorist would just drive over you!

Customers of the motorised mini-bikes shortly proved as imaginative in finding applications of the little machines as Di Blasi himself had been in designing them. The Italian National Police adopted mini-bikes from 1985 as auxiliary vehicles aboard Polizia Stradale force traffic helicopters. They also found worldwide use by a number of different 'chauffeur' operations who use them to ride and meet a customer, compact the bike into the boot of their car, then typically drive the client home from a bar or a party.

Di Blasi folding bicycles continued to evolve through a series of different designs to progressively reduce size and weight: the R20 in 1980, R50 (1984), R6 (1991), R4 (1995), R5, 20-inch wheel model R21, to the present R24 version in 2005.

The company has also produced folding pedal tricycles since year 2000, as models R31, R32, and R34. Further innovative ideas have gone beyond the field of transport with the development of a medical application sore treatment hospital bed with moveable elements to relieve pressure on specific parts of the body as an aid to recovery. At 99 years old, Rosario Di Blasi died on Christmas day 2008.

With Di Blasi's ingenious arrangements protected by patents, then folding imitators would have to find another way.

Where do we start with our second folder? It looks a bit like a suitcase on wheels! If you might not know what we're talking about, they say a picture speaks a thousand words ... then we'll try and describe the rest.

The AB12 Motocompo was a miniature folding scooter described as a 'trunk bike', and introduced by Honda in 1981.

In a simultaneous design exercise, it was specifically developed to fit into the boot space of the new Honda subcompact 'City' car (sold in Europe as 'Jazz'), and the car's luggage compartment was particularly arranged around the Motocompo. It's believed that the first 200 Honda Jazz cars in the UK had a free Motocompo in the boot as a marketing promotion, and very similar story is reported when the Honda City car was sold into New Zealand, which is where we caught up with our test feature bike at Pongakawa in the North Island.

In compacted state, the Motocompo seems somewhat like an Armadillo, all curled up to try and protect itself from anyone (or thing - pussycats maybe?) that might want to interfere with it. It'll only make sense when the pussies have gone and we've coaxed it out of the shell.

Basically, the footrests, handlebars and seat fold into the rectangular plastic body shell, to present a compact, suitcase-like package measuring 1200mm long × 500mm high (bars & seat packed) / 900mm high (bars up) × 300mm (pegs folded) / 450mm (pegs down). Wheelbase 830mm.

The steel disc-wheel/tyre size is 2.50×8, which is probably as small as it's practical and safe enough to go for a roadworthy motorised bike. The tiny telescopic front forks have limited compression of only 30mm travel, but should be capable of absorbing a fair proportion of road surface shocks, enough to manage the machine at limited speeds. The handlebars screw down separately onto the top yoke, through knobs on the top of each handlebar stem, and once removed, independently stow back into the body shell with all cables and wiring remaining connected. Forward indicators mount off the handlebar stems, and a small square speedometer mounts off the right handlebar leg, marked up to 30kph (18mph) in white, and 30 - 50kph (31mph) in red.

The single pad seat springs up on a frame, which is lockable in up or down position by a single trigger latch under the seat. Folded down position is within the bodyshell.

The plastic body panels comprise four basic mouldings, left side and right side, with the back lamp and indicator cluster housed within a rear trim section. A rectangular headlamp is located in the front of the body shell. The fourth moulding is a black one-piece body cover, folding with a plastic hinge, that keylocks into place in open (folded) or closed position when the handlebars and seat are stowed. Folding footrests and the kick-start tuck into nests within the outer body shell.

Peering into the gloom of the inner body shell, we can't see much ... cobwebs and spiders, and the rear springing is arranged by a single-sided suspension unit from the back of the transmission case, with the engine pivoting from the front in scooter fashion. You'd probably have to remove the body panels to make out or access much else inside, and we don't really want to get involved in that game (some of those New Zealand spiders can look pretty mean), so it's easier to resort to some specs for a little more information.

49cc, 2-stroke motor with crankcase reed-valve induction, producing 2.5bhp @ 5,000rpm, automatic clutch with single-speed transmission. Given weights: dry 42kg / wet 45kg, (roughly 6½ stone, and quite important if you've got to lift it).

OK, so let's have a further look around the bike and see what's involved in getting it to go.

There's a fuel dial set into the left body shell, off/on but no reserve since there's a petrol gauge set into the top of the ½ gallon tank, which should theoretically give some range up to around 95 miles on given consumption at 18mph, but we wonder if anyone could stand the boredom of riding one for over 5 hours at 18mph, just to test the claim?

The fuel system seems to be some sort of sealed pressure system, presumably to eliminate possibility of spillage when the bike might be stowed in a vehicle for transit.

The choke is lever operated by a small, yellow-tipped trigger off the steering headset, and there's a basic ignition key-switch on/off/lock. Lights switch on/off at a left handlebar control, there's also a horn button which produces a beep from somewhere within the body shell, and indicator switch. A small compartment within rear left hand of the body shell carries a small 6 Volt battery, with a sight port through the moulding to monitor fluid level, though how it might be accessed for service isn't particularly obvious ... no, we give up!

Another puzzle we find, is where a square plastic plug pulls out of the front RHS body trim, with two trailing cable lengths attached to a pin? What's that for? Well, we believe this to be the anti-theft system, for safely tying the bike up somehow, though quite how it's supposed to work, we have no idea. Has anyone got a manual for this please?

The rear brake has a parking latch on the handlebar lever, again presumably some feature for secure storage in transit.

A couple of jabs at the kick-start soon has the motor running, then leave a few seconds to settle down before easing off the choke until it runs clear without.

The motor and exhaust run smoothly and quietly, so all seems fairly harmless ... but throttle response proves quite sharp with the reed-valve induction, the automatic clutch grabs on, and acceleration is pretty brisk. So brisk in fact, that it's better to lean slightly forward when you're grabbing a handful - if you happen to be sitting back, then the front wheel can readily lift!

Having acceleration on such a small bike is certainly useful since it avoids the difficulty of being overwhelmed by impatient traffic away from junctions or lights. Motocompo's initial enthusiasm however doesn't last long, since just along the road, it seems to falter well before the urban limit, and all the traffic goes snarling angrily past.

The performance is seemingly restricted by a fairly low drive ratio as the revs top out into phased four-stroke running, which is probably just as well, since the errant handling characteristics have probably already taken us about as fast as any sensible person would want to ride it anyway.

With the tiny speedo whirring excitedly off the end of the 50kph dial, we clocked 39kph (24mph) by the radar gun on a downhill run, and it really wasn't going to go any faster than that.

Steering Motocompo is every bit the typically unstable, twitchy handling, small-wheel evilness that you'd expect it to be. It's best recommended to keep a secure grip on the bars and the bike firmly pointed in the intended direction, or any bump or pothole could easily become your undoing.

Everything else works adequately for the limited performance and pretty much the way you'd expect in the ordered world of Honda, brakes and lights all OK.

While you might imagine such a small bike with tiny wheels to be capable of turning on its own space, the reality is more ocean liner than sixpence - the limited steering lock means that Motocompo describes a 2.5metre (8-foot) circle to turn back on itself, so it's sometimes easier to just pick it up, than turn around in a confined space.

Honda's marketing projected sales of around 100,000 City cars, and 120,000 Motocompo mini-scooters per annum, but while the City car met and surpassed its annual targets, the Motocompo fell dramatically short, making barely a quarter of its plan.

The shortfall was based on some optimistic projection that 80% of City car drivers would want to buy the bike.

Low sales doomed the tiny scooter to an early grave.

A total of only 53,369 Motocompos were built when production ended in 1983.

Thirty years after introduction, in 2011, Honda released pictures of a new concept Motocompo, though little detail, and suggesting the possibility of a four-stroke engine up to 125cc.

A further concept electric scooter called 'Motor Compo' appeared at the Tokyo Motor Show in December 2011, so it might appear that the 'trunk bike' theme could be revisited?

Maybe Honda didn't learn enough first time around - people who drive cars generally don't much want to ride motor cycles as well.

Next -The answer is "234"

Now what adds up to the question?

If you think you might not understand, don't worry - it's just French mathematics!

This article appeared in the

October 2012 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012

M Daniels.]

Folders was another 'both-sides-of-the-world' production that might have worked out completely differently if the original intention had taken place years ago as planned.

There was a plan several years back to test another white Motocompo locally in Suffolk, however before this got to road test & photoshoot, the owners garage was broken into, and the little Honda stolen, never to be seen again.

It's particularly bad when this sort of thing happens to quite uncommon vehicles like the Motocompo, because they're rarely come upon and, after several years failing to locate another in the UK, we ended up flying all the way to New Zealand to cover Kelven Martin's red Motocompo in Pongakawa.

Riding the Motocompo as a 'yard bike' conveys a false impression that it might have loads of performance since the initial acceleration is quite snappy, and can aviate the front wheel if you're sitting back a little. The wildly optimistic speedo underlines the deception by readily flying off the end of the dial, and the tiny physical size of the bike makes everything feel faster than reality - but having encountered the old white Honda Motocompo on UK runs in the past, we already knew these were a real tail-end-Charlie bike with no top-end performance to be able to keep with the general rally pack. Kelven had barely run his Motocompo outside the garden, so when it came to choice of vehicle for riding along the road to our chosen test section, there was some surprise when Danny confidently opted to take the Phillips Traveller (export vrtsion if the Raleigh RM8).

"My little Honda will see that slow old thing right off - see you there later", and Kelven made a dramatic start, accelerating briskly away with the front wheel pawing the air. Yeah, real snappy ... up to a little over 20mph flat out ... then the lumbering old Phillips catches up and sails past at 30! "Bye, see you there later!"

The Motocompo notes were drafted together upon return, then worked in with background research over a couple more evenings. A few e-mail exchanges back to NZ qualified some minor detail queries arising in the text assembly, and the file was looking pretty much lined up to go out sometime as a stand-alone article - until just before the April 2012 edition 21 was due to go out, and we had to figure out the links to the third feature for edition 22,

There was suddenly an inspiration to match the Motocompo with a local Di Blasi, but nothing had been arranged to secure this second bike by the time we went to press, so the third feature links went in as three possible options of three part-developed articles. Any one of these could have made the final cut, but within just a couple of weeks, arrangements were secured on the Di Blasi, and the last minute Folders feature was suddenly looking the best reality.

Once the pairing idea was thought up, Folders really became the favoured option since it offered the possibility of a continuity link from the previous New Zealand special 22 edition, so we strove to negotiate access to the Di Blasi.

Rod Fryett from Lowestoft (just an hour up the east coast road), had been appearing at occasional local events for a couple of years on the smartly restored little compact, and it looked a really nice example to present in the feature.

It was just coming down to sorting a day, and timing to do the road test, photoshoot and taking notes.

There's always a need to get good light for the photoshoot, in a year particularly plagued by incessant rain, booking a pace bike for the road test because we never trust a speedo (even assuming our subjects have one), and an hour or so to take the notes. We normally have bikes in for a few days to arrange these suitable events at a natural pace, but Rod needed the bike for frequent use so it was agreed to watch the weather forecasts and try to do the lot in just one chosen afternoon.

Rod had imagined the process to be much briefer and less formal than we suggested, and remarked that it seemed an awful lot of trouble just to test his little Di Blasi - until we pointed out that we'd travelled 26,000 miles to New Zealand and back to test the accompanying bike for this feature.

There really is no answer to that!

The sun shone for the photoshoot, the pace bike turned up on time, the test went well, and as a folding design, the Di Blasi is a fiendishly clever piece of kit, literally expanded to ride in seconds! Anyone has to be impressed by that!

By comparison, the Honda Motocompo was quite a Meccano set, the handlebars were slow and fiddly to unpack, assemble and stow again, the plastic cover plate for the body not terribly convincing, then the performance ... comparing the two, you can really see why the popular Di Blasi has been in production for nearly 40 years and the Honda Motocompo discontinued in less than three!

Folders felt a really good article to produce because everything worked the way it should, everything happened on time, according to plan, all the research came easily, the words seemed to easily fall into a natural structure ... even though it involved a flight to the other side of the world, everything just seemed to go properly, and even the final text was completed weeks ahead of the editorial deadline. A great little presentation, which just had a feel-good factor all the way!

We'd had a sponsorship donation from mini-bike enthusiast George Smith sitting on the list for some time, and Folders seemed to fit the mini-bike bill, so George suitably scored the support credit on this feature.