Completely frozen over in the last ice age, James Motor Cycles at Gough Road, Greet, Birmingham, finally disappeared under the advancing Great Greet Glacier in the Pleistocene Epoch.

Subsequently lost for millions of years, finally, a combination of global warming in our modern times and the seasonal summer melt, finds an age-old chunk of ice breaking from the now receding glacier, then floating as a berg down the Grand Union Canal.

Frozen inside: some huge and ancient prehistoric machine, now long extinct.

Alerted by the government, IceniCAM scientists salvage the berg and return the frozen motor cycle to the laboratories for thawing out and forensic examination—but the mighty beast proves not to be dead! Overnight it revives and then goes on the rampage along the roads of suburban middle England—this is, Return of the Mammoth!

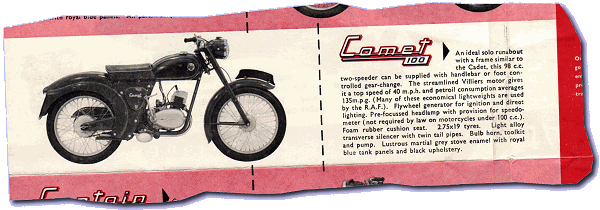

Introduced at the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show on 18th November 1948, as the James 1F ‘Standard’, it wasn’t until 11 months later that the ‘Comet’ name first appeared in a Motor Cycle description for the 1950 James range in the 13th October edition of 1949—the title only came nearly a year after the bike!

Comet’s lightweight rigid chassis was built, typically for the time, comprising a traditional tubular steel frame of brazed-lug construction and fitted up front with a girder fork set.

During 1953, a telescopic fork conversion kit became available for all the older models, and these forks were installed as standard in the J11 Comet model that took over for 1954, now fitted with a 4F engine and plunger rear suspension, which continued up to the end of 1955.

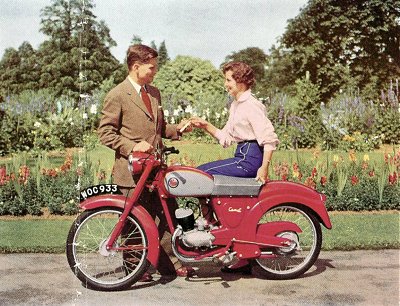

New for 1956, James adopted a common cycle frame for the new 100cc L1 Comet and 150cc L15 Cadet models and, instead of the established transfer branding, mounted plastic moulded James tank badges on rubber backing mats.

The cycle frame is distinctively styled in what may now be perceived as a particularly odd look of the time, but one has to consider what was going on over this period to appreciate why many motor cycles evolved to look as they did during this era.

The modern scooter emerged shortly after World War II but, in this age of post conflict austerity, was initially presented as just another form of economic personal transport.

The high demand for all forms of transport across the board meant a market for practically everything: autocycle, cyclemotor, motor cycle and scooter alike; every cost effective vehicle had its place—but, into the 1950s, the demographic began to change.

European societies emerged from the period of post-war austerity into a new time of aspiration and disposable income. Basically, people came to want better things and now could afford them. The old autocycles and cyclemotors were superseded by the moped but, while a family car often replaced the motor cycle, the scooter became fashionable and popular to buck the trend and actually increase its sales.

A number of motor cycle manufacturers in the mid-1950s, now becoming increasingly desperate for revenue, sought to dress up their motor cycles with rear enclosures and even body panels, simply to appear more like scooters!

Triumph, Norton, even Vincent, they were all at the game in the frantic plight to recover lost sales and, within the Associated Motor Cycles Group, Francis–Barnett and James were also changing their motor cycle designs.

Traditional tubular frame and brazed lug construction was giving way to press-formed sheet steel and jig-welded joints.

James had been producing the Comet light motor cycle since October 1948, and the 125cc Cadet since 1949, both traditional constructed models; to replace them would not justify the expensive investment of individual new chassis for both models. The consequence was that, new for 1956, the very same cycle frame was employed for both the latest L1 Comet 100cc and L15 Cadet 150cc models.

There’s certainly some advantage associated with this policy, as the cycle chassis is going to be engineered up to the standard demanded by the larger and more powerful model—but there are also disadvantages, as the smaller capacity machine is likely to appear overweight and underpowered. The scooter-influenced and semi-enclosed tail unit of the frame is a considerable and voluminous construction, much like an upturned metal bath. It rather looks as if there are no suspension units from the rear frame to the swing-arm, and motor cyclists of today could be forgiven for presuming it might be an early monoshock—but rising-rate suspension design had some way to go in the 1950s. The rear swing-arm is actually quite conventional and controlled by a couple of fairly hefty forward-mounted springs within the rear body enclosure, which is why the panels are so large in order to contain all the working parts.

Earlier rigid and later plunger Comet model frames, built by traditional tubular and brazed lug construction methods, were physically quite small machines—compared to which, the L1 chassis is a veritable mammoth! Then, further considering this full-size body was intended for the larger 150cc, three-speed Villiers 30C motor, when you fit a little 99cc, two-speed motor, it looks somewhat small and disproportionate: where’s the engine? Ah, that’ll be it, hiding in the corner! The motor installation may not look quite right from the left hand side where 3½ inches and 5 inches of top and bottom chain runs are exposed before disappearing back into the main body of the frame, but you wouldn’t originally be seeing this since there’s a trim missing.

Specifications for the L1 Comet and L15 Cadet in 1956 only quoted both models with a single-saddle plus rear carrier mounted atop the mudguard body. The two machines were listed in the same single-saddle standard configuration for the following year, though a dual-seat optional fitting, reportedly only for the 150cc Cadet, became available in 1957. The dual-seat was only listed as standard equipment for both models in 1958, and would appear an unlikely original fitment for our L1 Comet in 1956, which would normally be expected to have the single-saddle and rear carrier arrangement.

Noting that the dual-seat appears to be matched by a pair of suitably period rear footrests, we wonder if this bike might have originally been a 150cc Cadet downgraded by a retrospectively fitted 4F engine?

The frame number will tell us … 56 L1-1239. Well, that seems to confirm that it was originally built in 1956 as an L1 Comet, so it looks as if someone retrospectively converted it to dual seat configuration!

The handlebar set looks nice and tidy with its welded-on yoke mounts and lever brackets, but really doesn’t suit the fitting of the 4F gear trigger-change mechanism in any practical operational position, or allow any routing of the gear change cable that looks even remotely correct. There’s getting to be a few aspects about putting a 4F engine into the L1 that look like rather poor compromises.

With the help of a number of handy staff, our keepers manage to herd the reluctant mammoth onto the scales to check its vital statistics, 6 stone 5 pounds front, 7 stone 5 pounds rear: 89 + 103 = 192 pounds wet (13 stone 10 pounds or 87 kilogrammes), what a lump! Adding an average rider will double that weight, and a further passenger just doesn’t bear thinking about … poor little 4F engine!

The siting of the 4F cable operated trigger-change mechanism on the right-hand bar was obviously going to present considerable operational issues as the front brake lever mounting bracket is welded to the handlebar, and places the trigger-change 3 inches from the twistgrip. Consequently, you have to take your hand from the throttle completely to effect a gear-change, which is a horrible and clumsy operation with this mechanism, and to say there are going to be ‘issues’ is a major understatement. Meanwhile, your right foot is sitting on the footrest with absolutely nothing to do … please Villiers, get on and invent the 6F foot change motor!

Villiers S12 carburettor is listed as having begun to replace the original pre-war ‘Junior’ carburettor from early 1957, so again we’re left wondering if the fitted S12 carb might have been ‘updated’ similarly to the saddle? Once we’d got the motor running after a lot of kicking and fiddling with the choke, the engine seems to run very well on the throttle in neutral—crisp, clean, revvy and responsive; not at all what we’d expect from the usual F-series motor, so the S12 must be right on the button—just a nuisance about the difficult starting, but perhaps that’s more a quirky matter of knowing the correct choke setting, flood procedure and throttle required to start.

Clutch cable adjustment feels OK when you pull the lever in, but does little to soften the grinding crunch when you notch the gear trigger into first. There’s no getting away from the nasty cable change arrangements on 1F and 4F motors. When everything is in good condition, set to perfection, and the trigger positioned close at hand, then they can be just about tolerable—but when they’re old, worn, tired, and the trigger’s out of reach, then they’re just awful!

Letting out the clutch you now have two choices:

Gently open the throttle, gently feed in the clutch, and make a slow and measured take-off, or

Nail the throttle wide open, mercilessly slip in the clutch, and make a slow and noisy take-off.

Basically, the operative word here is ‘slow’. The bike is too heavy, the gearing is too high, the motor is too low powered, and you really can’t make a fast take-off. It’d probably be dreadful attempting a hill start—don’t even think about it! Get up a decent pace in first to prepare for the jump into second (top), and then brace yourself for the inevitable dog-crunch as the gear blunders in.

Top feels like overdrive as soon as you let the clutch out, and pretty much requires all available throttle to accumulate any more speed. Once you’ve managed to coax the lumbering brute up to around the urban limit, then the pace can be reasonably managed by a combination of the engine revs then being generally in its better torque zone, and maintained momentum.

If you want to go faster however, it feels quite a long and struggling process to build up much more speed, so there comes a quickly developed tendency to ride harder through corners so as not to drop pace. To its credit, L1 handles corners well, so readily lends itself to this compensating technique, but basically, it’s over-geared and underpowered.

You also find yourself taking advantage of gravity opportunities from any downhill, to snatch up a little more speed—since you know it’s only going to fall away again, and you’re never going to develop any concerning revs out of the motor under general conditions.

The lumbering mammoth is never going to be able to maintain any consistent cruising pace due to the nature of the beast, so you soon adapt your riding style to allow for the bike’s shortcomings and general lack of power.

The cast aluminium silencer box bolted under the frame, with outlet tailpipes venting on both sides, presents a very pleasant exhaust tone as the system effectively smoothes out the power pulses leaving a low constant drone under load, but a promising crisp note when revved. The sound is good, but the pipe jointing not so good. The exhaust pipe and both tailpipes appear to just ‘plug’ into the alloy box with no evidence of any effective sealing and almost seem designed to leak from everywhere, which is just going to cover most of the lower bike liberally in oily yuk!

Best on flat: 39 in full crouch with light tailwind. Downhill run peaked at 47mph and, despite fading on the uphill climb, L1 crested the rise, still in top gear, at a creditable 29. The seemingly good performance figures present, however, a rather false impression of the actual ride. The 4F motor was constantly labouring against our mammoth’s mighty body mass, a battle the engine could never win. It proved practically impossible to get the motor to pull revs on the flat in a normal upright riding position, when the bike just droned along in a hopelessly over-geared state. To achieve the best on flat reading required holding a tight tuck for some half-a-mile to slowly creep up the pace, and the motor instantly loses this speed again the moment you sit up.

The downhill run result was undoubtedly assisted by the high final drive ratio and the effects of gravity on our mammoth’s hefty mass. (It should be noted that we did check the fitted front sprocket was the standard and correctly specified 14-tooth—no smaller size is available.)

In positive points, the sumptuous dual-seat was positively luxurious. You could sit on that all day, the pad being 2 feet long and 1 foot wide with ample space for both rider and a passenger. The sheer physical size of this machine offers a comfortable seat for even the larger rider, though a larger rider will only further disadvantage the underpowered two-gear motor—catch 22! The prospect of how effectively the 4F engine might pull this already overweight bike with a pillion passenger aboard as well might be another matter!

Both front and rear suspension worked particularly well for a machine of this capacity, and handling was generally quite good. The bike felt well planted on the road at all times and rode bumpy surfaces so effectively that you would be barely aware.

Rear foot brake proved effective enough, though the front rather less so, and left us wondering how much more inadequate it might become when the same cycle frame was fitted with larger capacity motors of more capability?

Indications from the 86mph Smiths magnetic speedo proved quite comical once we got underway. Something obviously wasn’t quite right, as the needle rotated clockwise, the dial vibrated anti-clockwise! Any further guess at making any sense of the reading was further confused as the needle swung wildly over some 30mph range and, on the downhill run, was well off the clock and coming round for a second lap! Good job we had the pace bike.

All the crunchy gear changes were a most hateful operation that the rider would quickly despise and try to avoid as much as possible, even to the cost of labouring the motor and abusing the clutch.

Our L1 has a direct lighting system with no battery—headlamp is given as 6 Volt × 24/24 Watt … no, that doesn’t work, and taillight is given as 6 Volt × 3 Watt … no, that doesn’t work either.

The Italian CEV beam/dipswitch with horn button wouldn’t seem likely to be original equipment, and there doesn’t even appear to be any electric horn mounted on the bike. Base models at this time still relied on a squeezy bulb hooter and, in 1956 didn’t even suggest an electric horn as an optional extra.

As the 6F foot-change engine became available for 1957, the Comet was offered as with either 6F or 4F engine options. An electric horn finally became a standard fitment and a conventional chrome-plated silencer system replaced the cast alloy exhaust box.

The foot-change engine became the standard fitment in L1 Comet models for 1958, though a 4F installation still seemed to be available upon customer request right up to 1961.

Francis–Barnett was taken over by Associated Motor Cycles Group in June 1947, who further acquired James in 1951 as the business fell into financial difficulties.

Francis–Barnett had dropped its last Powerbike 56 autocycle in 1951, while James continued its final 2F propelled Superlux autocycle until July 1954, at which respective times both autocycles had been completely individual machines.

As Francis–Barnett and James Motor Cycles were both listed as holdings of the AMC Group, the older machines were superseded as the 1950s decade wore on. Francis–Barnett at Coventry and James at Birmingham were already separately manufacturing comparative machine models using exactly the same Villiers engines, but AMC’s extensive tooling investment came with a further penalty that demanded both these separate utility motor cycle companies use common cycle parts too, so this successive generation of new models largely became badge-engineered versions of the same generic formula.

When the James L15 Cadet with Villiers 30C 147cc engine was introduced in 1956, the Francis–Barnett model 73 Plover was ostensibly the same machine with little more than just different badging and colour.

As the James Cadet evolved into the model M15 for 1957 with dual seat, conventional silencer, electric horn, etc, Francis–Barnett mirrored exactly the same changes for their Plover 78 model.

Practically every James motor cycle in the late-1950s’ range had an equivalent Francis–Barnett model—except for the James Comet. Discounting their autocycles, Francis–Barnett never manufactured any light motor cycle under 125cc after the 98cc model K49 Snipe in 1940.

Francis–Barnett production moved from Lower Ford Street at Coventry to become merged with the James plant at Gough Road, Greet, Birmingham 11, in 1962. The two companies had been producing practically the same bikes for 6 years; it was just surprising that the two manufacturing units were separately maintained for as long as they were!

Comet L1 models continued into the 1964 season but dropped from the range before the New Year.

The real reason behind the end of the James Comet probably wasn’t prompted by any particular decision to end the model for any other reason than Villiers having discontinued manufacture of Comet’s 6F engine in the early 1960s, so James had found the model without any motor when their last stocks of batch 607B finally ran out.

The same 6F engine situation almost certainly sealed the end for Excelsior’s Consort model at much the same time, though that company was also suffering trading difficulties at that stage too.

James motor cycles technically concluded on 4th October 1966 due to collapse of the Associated Motor Cycles parent group.

Next—Yes, it’s another class in French, and time to confess, this is actually a lesson we’ve been trying to avoid for quite a while. Well our luck has well and truly run out now, caught in the cloakroom by the headmaster, and now we’re headed for a spell in detention.

These particular bikes seem to become a passion with some people, a bit like Marmite (or maybe in this case, snails or frogs’ legs?) you either love them, or desperately hate them; there is simply no in-between!

When this very original and low usage model came through the workshops for attention, it really seemed a sign that couldn’t be ignored anymore. We thought ‘OK then, it must be time now; we’ll give it an honest chance’.

It’s an old & black medieval thing from the dark ages, it’s got the engine on the front, and … it’s French.

This article appeared in the October 2012 Iceni

CAM Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service. The

Frozen James picture was created by Andrew

Pattle for Iceni CAM

Magazine using original photographs by Andreas Tille

(ice block) and Mark

Daniels (motor cycle) and is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Please contact us for a higher

resolution version.]

[Text and photos © 2012

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service. The

Frozen James picture was created by Andrew

Pattle for Iceni CAM

Magazine using original photographs by Andreas Tille

(ice block) and Mark

Daniels (motor cycle) and is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Please contact us for a higher

resolution version.]

The L1 "Mammoth" feature was very much an opportunist article, taken when the bike passed through the workshops for a bit of attention, and just a convenient time to bag & tag this particular Comet light motor cycle model that we’d had on the ‘want-to-do list’ for some time.

The early cast aluminium exhaust box models are particularly interesting for this unusual feature that was abandoned for a conventional silencer within just a couple of years.

Compared to earlier Comet models, the L1 is a huge and heavy machine, a physically big motor cycle chassis primarily intended for a three-speed, 150cc engine, but installed instead with a small and underpowered two-speed, 99cc motor.

Owner Mick Cousins from Ipswich is a large gentleman who can find smaller mopeds and the like quite cramped and uncomfortable, which is where the luxurious mammoth scores particularly highly.

The L1 offers a good and comfortable ride compared to many of its contemporary autocycle stablemates, but is rather compromised by a lack of power and diabolical 4F trigger-change gears.

Practically every motor cycle in the post-war James range was mirrored by a Francis–Barnett equivalent model. By 1956 the Francis–Barnett model 73 Plover with Villiers 30C 147cc engine and equivalent James Cadet L15 with same 30C engine were, ostensibly, exactly the same bike–same frame, same engine and cycle parts, just different colours and badges.

However James continued its 99cc Comet light motor cycle class right up to 1965, when Villiers had finally declared the F-series motor obsolete, Francis–Barnett had never concerned itself with any comparable F-series powered light motor cycles.

The road test and photoshoot were completed at the end of April 2012, then taken by Danny as a set of notes and research file to Cyprus in thw first week of May, for draft writing at the Agios Georgios villa like article number 3.

So much content developed in the draft that it was clearly heading for a ‘stand-alone’ feature. As the ‘frozen mammoth’ idea worked out, it seemed a natural progression for Andrew to create the ‘iceberg’ picture to accompany the text, and there were several rejected efforts before the final version.

The Mammoth article was also a prime candidate for further franchise on to the British Two-Stroke Club Independent magazine, so licensed publication of this feature always looked quite a likely prospect to extend our promotion of small capacity machines.

Production costs were negligible since the bike only came from just across town, but the workshop needed to spend several hours sorting out the bike to road test standard.

Sponsorship was collected by Robin Cowling of Suffolk Section VMCC, so a local article all the way!

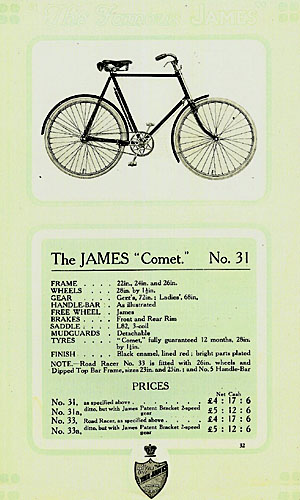

Just a postscript to Mark Daniel’s article, ‘Return of the Mammoth’, about the L1 James Comet: The ‘Comet’ first appeared in 1932; it was a 148cc twin port two-stroke of James’s own manufacture.

David Wells

James’s first use of the ‘Comet’ name was even earlier than 1932—but it was a bicycle. Before the First World War, James was applying the name ‘Comet’ to its cheapest range of bicycles. Presumably the fact that the Comet was at the bottom of James’s pedal cycle range was what led to its use on James’s smallest capacity motor cycles.