Since demand for economic transport became so great in the early post-war years, there wasn't initially much need to be particularly concerned about sales, since pretty much anything that was produced was going to be purchased by someone and, for a short time, many manufacturers found themselves in an enviable position of being able to sell practically any two-wheeled machines they made, whatever they might be.

The late 1940s ran into a veritable boom time of the early 1950s and the Italian motor cycle industry enjoyed a particularly buoyant period into the mid-50s - but big bubbles often have a tendency to pop...

Exactly the same effect happened across many of the European motor cycle manufacturers at much the same time, from Germany to Italy, France to Britain, all these countries began to emerge from the years of post-war austerity, and their societies evolved a greater disposable income. In all the recovering nations, demand for motor cycles progressively became replaced by the purchase of motor cars and, in Italy, it was modestly-priced Fiat models that typically began to take the sales.

The effect of declining Italian motor cycle sales became quite apparent in 1958 as, unable to sustain the escalating cost of competition, Moto-Guzzi, Mondial and Gilera all withdrew from international racing. While motor cycle sales became particularly poor, the motor scooter seemed to experience a degree of immunity because of a fashionable popularity for this type of machine, which found a number of Italian motor cycle manufacturers belatedly looking towards the scooter market for salvation.

Between them, Piaggio Vespa and Innocenti Lambretta had practically come to dominate the Italian scooter market since the late 1940s, and the situation indicated some level of desperation that other manufacturers might even presume to compete so late in the day. Agrati Garelli and Motobi were examples of a couple of respected and established companies looking towards a share in the market for small capacity scooters in the late 1950s, but a surprise offering by Laverda in 1959 seemed very late for the party!

1950 Laverda 75

Laverda derives from the ancient Latin title for a Roman Guardia, becoming the adopted name for small North Eastern hamlet and, subsequently, also some of its inhabitants. During the 1700s, some members of the Laverda family moved to the neighbouring village of Breganze, near to the town of Bassano del Grappa, in an area known for growing olives and grapes for the production of oil, wine, and particularly distillation of the potent locally produced spirit Grappa.

In 1873, Pietro Laverda founded his firm, Ditta Pietro Laverda, initially making small agricultural equipment such as wine and olive presses. The Laverda firm continued to develop in the production of agricultural machinery right through until after the Second War when, still as a family concern, Pietro's grandson Francesco became interested in the prospect and opportunities of motor cycle production and decided, in 1948, to develop a small 4-stroke model in his spare time. Hand-making most parts at his home workshop, the first Laverda motor cycle was completed in 1949 with a 74cc motor of 46mm bore × 45mm stroke, reportedly producing 3bhp @ 5,200rpm for a (possibly optimistic) claimed 45mph top speed. The all-alloy engine having an iron cylinder liner and pushrod operated valves was of unit construction with a three-speed, foot-change gearbox.

At a time when the availability of personal transport was at such a premium, five replicas were shortly made to satisfy interest of Francesco's closest friends ... so production had started and, upon completion of these initial models, Moto Laverda SpA was registered as a newly incorporated company to manufacture motor cycles. Second generation 75cc models introduced a significant redesign for the 1950 build, with ongoing developments being added during the year. Production for 1951 achieved 500 units and Laverda now sought to publicise their product by entry in the Milano-Taranto road race, but the attempt was not completed due to carburettor failure. Though the 75cc class competition was won by Capriolo in 1952, all four team Laverdas completed the event at the second attempt, and returned even more highly tuned for the following year. Possibly in a tactical effort to unsettle the opposition, Laverda (maybe generously) claimed 10bhp @ 12,500rpm from their engine with a forged high-compression piston, bigger valve head, high lift cam, and larger carburettor - but it certainly seemed to work as their bikes took the first 14 places!

A 52mm bored and 42mm stroked motor resulted in a new '100' model, and there were now three versions of the 75, from a basic 'Touring' 3.7bhp @ 6,500rpm for 40mph, a 4.7bhp @ 6,700rpm for 55mph 'Sports' model, to the now four-speed 'Customer' competition 5.5bhp @ 8,600rpm. Newer OHC competition bikes by Ducati and Ceccato began to outclass the Laverda pushrod motor by 1956, and sales of the 75 and 100 models fell back to just 200 machines in 1958. Production of 75s and 100s together had peaked at 9,000 in 1954 which starkly illustrated the dramatic decline of Laverda's motor cycle division. The 75 was dropped, though the 100 remained on list until 1960.

The general downturn in two-wheeler business was compromising a number of competing Italian manufacturers such as Capriolo, Parilla, Moto Rumi and Sterzi, who were mostly caught with all their eggs in the one motor cycling basket. The Laverda group however included agricultural machinery, caravan manufacture, and industrial foundry work, so to some degree its diversity rather insulated the risk, though something certainly needed to be done if Moto Laverda was to continue in the business of producing motor cycles - which is pretty much where we came in.

Laverda is largely remembered today for its large capacity and exotic sports motor cycles, the Jota 1000 triple, SF 750 twin and Montjuic 500, etc, but many may not appreciate the legend these created in later years was grown from humble beginnings in small capacity lightweights.

It may be surprising news to a number of readers, but at the Milan Show in late 1959, Laverda presented a 50cc scooter! Not only may this be difficult to imagine today, but was further unusual since the engine, remarkably, was a four-stroke! This tiny pushrod motor of 40mm bore × 39mm stroke rated 49cc for 2.5bhp @ 6,000rpm driving through a two-speed gearbox mounted in a diminutive 120lb (just 8½ stone or 55Kg) body shell, and reputedly capable of 30mph+. The design was specifically aimed toward the recently introduced Italian no licence/no tax market specification.

The 50cc single-seat scooter was joined by a slightly larger 60cc, three-speed model the following year, and the original two-speed gearbox became standardly replaced with the new three-speed cluster for both models.

Rivals: Laverda and Tina

The first examples of Laverda scooters seen in the UK were the 50cc two-speed listed as imported by Scootamatic from September 1960 to April 1961, priced at £93-9s, and were displayed at the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1960 on Scootamatic stand 83, along with a selection of Auto-VAP and VeloVAP mopeds, Agrati-Garelli Capri & Como scooters, Honda C100 Cub, and the British built Elswick-Hopper Lynx moped prototypes with VAP57 engines.

Formed by the management of Elswick-Hopper, Scootamatic Ltd was a new company specially set up to handle distribution and sales of imported scooters and mopeds, and prospective manufacture of Elswick's own Lynx moped, though this machine was subsequently dropped in favour of factoring the Auto-VAP model range instead. While Scootamatic took up an initial licence to import and market Laverda into Britain, they declined the Honda at the time, thinking it wouldn't sell (a rather epic error of judgement, and probably much rued just a few years later). The Scootamatic managing director subsequently went on to register his own organisation as Eric R Sulley Ltd at Vincenza House, 4 Derby Street (near Woolaton Square), Nottingham, and adopted the licence to import and market Laverda Motors products into the UK, starting with the new 200cc-twin motor cycle and the 60cc, three-speed mini-scooter in June 1962.

Sulley's official launch of 27th March 1962 at the Royal Festival Hall was somewhat pre-empted and upstaged by the earlier March introduction of Triumph's new 99cc Tina scooter, very competitively priced at £91-7s-5d. This untimely surprise probably caused some hasty last minute compromise to the pricing plans as Sulley announced an initial retail price of £93-9s (89guineas) for the Mini 60, a reply obviously pitched to appear closer to the Tina. Unfortunately however, this was exactly the same figure that Scootamatic had posted the original 50cc two-speed mini-scooter for 1 year earlier, and wouldn't appear a particularly credible price for a later 60cc, three-speed now including a dual-seat and spare wheel!

A sales/price contest between the Mini 60 and Triumph Tina had begun - even before the Laverda had reached the showrooms!

A listed price for the Mini 60 posted in the May 1962 edition of Power & Pedal seemed to be reduced yet again, now down to 87½ guineas - a guinea and a half cheaper (£91-17s-0d to save you the antique maths), but the unrealistic attempts to compete appeared to be over the following month as machines finally arrived for sale in the showrooms - and the actual selling price was finally posted at £99-15s (very nearly 8 guineas more than the Tina).

The UK Laverda range was further joined by the 50cc mini-scooter from November 1962, now with the three-speed gearbox and priced at £95-0s-2d.

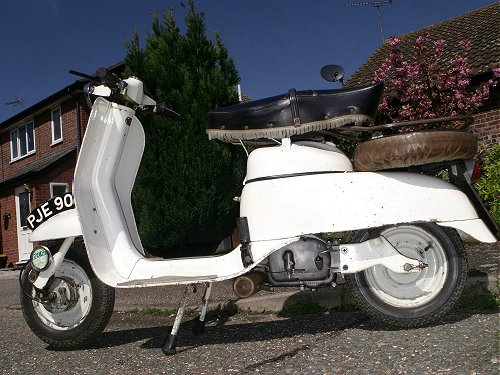

Only when prowling around the Laverda 60cc mini-scooter can you actually appreciate what a miniature machine this really is! Though having a slightly larger body-shell than the Mini 50 and now weighing in at 139 pounds (nearly 10 stone or 63kg) it's still a very small bike, and you have to wonder how a tall person might fit aboard - so we ask a 6ft 2in gent to try it for size! Andy looked quite puzzled as to how to fit his knees into the leg shields, and how to get his size 11 shoes into the forward footplate to operate the brake pedal. There seemed a hopeless clash of knees and elbows, at which we suggested maybe sitting further back on the dual-seat? That just about resolved getting the feet aboard OK, but now left no prospect for a passenger, and then required a hunched forward lean to reach the handlebars - no, completely hopeless, you have to accept this scooter comes with a physical size limit!

It's therefore probably no surprise that the adopted advertising angle was particularly biased towards women: "For Know-Where-They're-Going Girls..." and "...a real woman's scooter". Further advertising in the Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader claimed to be "Reaching a whole new market of gay young women at the price they can afford" ... "Bright young advertising in 'Career Girl' 'Weekend' 'Photoplay' - the magazines they all read".

Trade and retail advertising for the Laverda scooter

You can't help but notice the saddle is trimmed all the way round with a 'fringe'. No, not a fashionable aftermarket addition, but an original feature - all the Mini 60s had tassels around the seat! Was this an early idea toward feminine identity market branding?

The cast aluminium handlebar cover houses a small, round, and typical moped-type 50mph VDO speedometer, but the headlamp comprises a separate 4-inch CEV proprietary market unit.

We cautiously observe the forward operation kick-start has no folding head, and menacingly sticks out 3 inches from the bodyline at just the right height to crack your shin as you inattentively brush past, or catch on objects as you navigate the bike about your garage.

Transmission from the motor to the rear wheel is by a very short but conventional drive chain, which is covered by a face trim, though open backed and not at all maintenance-free, so the owner will still need to keep this lubricated. Possibly a sensitive point considering the drive chain is very much 'out-of-sight and out-of-mind', being covered over, low down, and under the body panel.

Approaching the scoot from the left hand side (which most right handed people will naturally do), trying to locate the stand leg by feel alone can't really be achieved since you invariably catch the clutch operating arm or exhaust tailpipe instead - anything but the wretched stand leg, so you nearly always have to glance down to see what your foot is doing ... not a major issue, but it's just a bit annoying! The forward footplate pretty much tails away where the main body panel starts, so a pair of folding pillion footrests are mounted off the front of the body section.

The structural centre ridge spine of the monocoque frame is trimmed with a small rubber mat between the footplates, which catches our eye, so we investigate further. Lifting the mat finds a discretely hidden cavity for the footbrake cable linkage, and possibly a useful compartment for stashing some basic service tools, spanner and spare spark plug. The petrol tap is fairly obvious, a chrome lever sticking out the front of the main body, turn down for on and across for reserve. There's no key-switch, so just kick and go ... well maybe it works like that in nice warm Mediterranean countries, but a cold and damp English morning is quite likely to require a bit of choke - except there isn't one!

There are now two options: Stuff a rag into the air intake on the right hand side-panel and hope this strangles the carburetter enough to enrich the mixture, or as a last resort, unscrew the finger-wheel in the middle of the rack, tip back the seat and the petrol tank, then press the tickler button to flood the carburetter - which really serves to convince us that the bike was never quite intended for cooler northern markets. It's also necessary to unscrew the finger-wheel and tip back the seat to fill up with petrol; however, the hinged fuel tank remains down for this operation.

Several fruitless kicks later and we're encouraged to persist by a few occasional firings, and then eventually manage to get the motor to catch. Not wishing to repeat the starting rigmarole, we sit patiently to warm the engine well before risking any premature stall.

The exhaust tone is very muffled and subdued, though the engine beat rings clear and strong with good response to the throttle. Even before setting off, there's a confident feel about the way this motor runs.

Clutch lever operation proves a little heavier than might be expected for such a small capacity machine, though we're not sure this may be due to dried lubricant in the cable, particularly when we feel the clutch slipping-in to drive. Since the bike has not been recently serviced or seen use for some time, then we will probably need to make some allowances. Gear selection feels very positive in every ratio going both up and down the box, but the twist-shift is relatively heavy to turn (again this may be gummy cables) so the change is firm and fairly slow. First gear proves very low, presumably selected this way to enable the bike to pull away two-up and be capable of climbing any adverse incline. The motor soon pulls through second and into third, so you readily develop the impression that the overall gearing feels fairly low as the motor is quite busily humming away within the urban limit. Exchanges with our pace bike establish the 50mph speedometer seems to be indicating 10% fast at 30, so comfortable cruising seems to be around the high twenties, though a fair amount of vibration comes through the bars even at this moderate speed and does suggest that anything more than short journeys could become tiring without wearing gloves.

We run a few miles to get the motor warm and settled before turning before a tailwind for the flat run, in a crouch, with indicated 40 and pace bike reading actual 36mph. The downhill run achieved best indicated 45 while pace bike recorded 41 as we got a run-up to charge the hill. Speed progressively fell away on the following climb until the motor settled back to crest the rise at indicated 27 (pace bike reading 24). Laverda gave a good account of itself on the ascent section, always feeling strong enough to remain in top gear all the way. We were quite impressed with the little Laverda 60 engine, which felt hearty and confident throughout the run, and surprised us that it had so much more performance beyond the urban 30 limit. The motor felt quite comparable to a Honda 50/70, running smooth, revvy and eager to go, though with a fair amount of noise and vibration so a rider would probably be unlikely to maintain full speed for other than short bursts - sounding and feeling a bit like sitting on some white goods appliance on spin cycle.

When we pull up after our run, the engine is ticking over nicely, but how to stop it? There's no cut-out button on the handlebar switch, just lights beam/off/dip and horn. Stalling the motor in gear doesn't seem likely ... then remembering that the Motom 60S we tested a couple of years back had a hidden stop button under the headlamp ... we feel around ... and, yes, there's something there, press that - and the engine stops.

The small diameter wheels conveyed the usually expected impression of wandering handling while the trailing link fork set didn't help either by delivering a hard ride from the front suspension, though the rear proved more effectively sprung. The cable operated rear footbrake was disappointingly poor, while the front hand-lever felt heavy and didn't stop particularly well either, though some of these effects may be a consequence of drum brakes suffering from lack of use or recent service. The Italian period hard-sprung mattress saddle seat was typically firm and never suggested any comfort, while its glossy cover felt slippy to sit on. The AC direct lighting set produced comparable headlamp illumination to typical period mopeds - dimly adequate, but the 'glowing ember' tail lamp could only be detected after dusk and would not be observable in daylight running.

Triumph adjusted the Tina pricing upwards to £94-10s in December 1962, which still left them a comfortable 5 guinea advantage over the Laverda Mini 60 sale cost, and so the margin was maintained until April 1964 when Triumph increased their selling cost to £99-15s, exactly the same posted price as the Laverda! By 1964, Triumph's marketing people were well aware that the Laverda presented them little real sales threat on the high street, but still didn't want to appear at any cost disadvantage, so matched the exact cost for a further period. The comparative costing study of these two rival mini-scooters certainly illustrates the keenness of competitive price listing in the early 1960s.

By the time the Laverda 60 mini-scooter came on sale in the UK in the summer of 1962, back in Italy its production had already been discontinued! Manufacture of mini-scooter models at Laverda only lasted for two years. The 50cc model was dropped from production toward the end of 1961, and the 60cc version ended in 1962. Laverda were still trying to flog off old stock over 5 years later!

Considering the imported Laverda 60cc, three-speed mini-scooter had to be priced at £99-15s to even be worthwhile retailing by Sulley's organisation, and the home manufactured Triumph Tina 99cc with 'simpler to ride' automatic transmission was so much lower priced ... it's pretty obvious which model sold, and which didn't!

Sales of the Laverda mini-scooter models proved so poor they even failed to recoup the tooling cost, but just about when it looked as if someone was going to lose their shirt ... fortune smiled, and Montesa in Spain took up licence on the design to build the model again as the Montesa 'Micro' from 1962 to 1965, so Laverda managed to recover some of their investment and eventually managed to just about break-even on the project.

The Mini 60 price increased to £108-13s-7d in February 1965, and was only cost overtaken by Triumph's remodelling of Tina into the T10 scooter for June 1965, when that price went up to £109-4s.

Despite early technical problems shredding Tina's reputation, over 20,000 of these original model machines were built up to June 1965, before Triumph revised the design to re-launch it as the T10 scooter. The Triumph Tina and T10 models undoubtedly compromised the prospects for the Laverda 50 and 60 Mini-scooters in the UK and imports respectively ended in August and September 1967 (which is probably a best indication of when old stocks back at the factory were finally cleared).

Somewhat ironically, after declining the licence to import and distribute Honda models into the UK at Scootamatic, Eric Sulley went on to become Head of Sales and Marketing at Honda GB. UK sales of the relatively expensive Laverda Mini-scooters proved particularly sluggish, few were bought and surviving examples are quite uncommon. The Triumph T10 scooter continued up to June 1970

Fiat Trattori acquired a 20% initial stake of Laverda Macchine Agricole shares in 1975 and by 1981 had completely taken over the agricultural manufacturing side of the company. The Laverda family passed the motor cycle business into administration in 1985. In February 1987 the receivership court of Vicenza assumed ownership of Moto Laverda srl with all its land, machinery, warehouses full of remaining motor cycles, spare parts, designs, projects, drawings and technical archives.

A worker's co-operative negotiated a takeover from July 1988 and re-launch of the business as Nuova Moto Laverda by May 1989. The co-operative foundered in 1993 and was purchased by millionaire Francesco Tognon, who set about re-launching the brand again with an updated range of sports bikes, but this venture collapsed again in 1998.

In 2000, Aprilia bought out all rights to both Moto-Guzzi and Laverda, and then imported a range of Asian manufactured low-cost scooters and quad-bikes primarily to sell mainly on the Italian home market under the Laverda brand - it wasn't a popular exercise. At the 2003 EICMA Motorcycle Show in Milan, Aprilia presented a new Laverda-branded SFC prototype based on their RSV1000 model, but the Aprilia Company was in dire financial straights and became taken over by Piaggio in 2004, all rights to Laverda being included in the transfer.

Piaggio has subsequently quietly wound down activities related to the Laverda brand and publicly advertised a willingness to sell all rights to any potential investor. Currently the Laverda motor cycle brand is not in use, and Laverda.com redirects to the Aprilia website. Fiat Agri sold on half the Laverda M A shares to Argo SpA in 2007, and the remaining 50% in early 2011, Argo being the group behind other agricultural brands such as Valpadana, Landini and McCormick. Laverda Macchine Agricole Breganze plant continues to manufacture agricultural products, chiefly combine harvesters, but is now wholly independent from the Laverda family.

Next -Right you lot! It's come to our attention that there have been a large number of pupils falling behind in their foreign languages, and since the school governors accept no excuses for poor results, it's going to mean extra "French Lessons" in the coming edition. Yes, there'll be more homework on vélomoteur, cyclomoteur and BMA histories, so you'd better pay attention - there are going to be exams afterwards.

This article appeared in the October 2012 Iceni CAM

Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012

M Daniels.]

The Laverda scooter feature was one of those articles that went through our system on the fast track, because it was an unusual machine (and we like to deliver these 'rare' features quickly), and there was also the bonus of being able to franchise another version of this article on to the Vintage Motor Scooter Club magazine - and just in time, since they'd nearly caught up running the last sequence of articles we'd given them back in 2011 (DKW Hobby, BSA Dandy, and Triumph Tina).

As part of the John Truluck collection, we'd earlier seen the bike while developing features on his DKW Hobby for Part of the Union, and a BSA Dandy in That's Just Dandy back in 2010, and we expressed an interest in testing Mini 60 "sometime..."

Seeing John again at the EACC 'Daffodil Dash' event in March 2012 refreshed our enquiry after access to the Laverda, which was no problem, but we'd have to be quick since he was thinking of selling the bike and already had someone expressing interest!

Well, there wasn't much to think about, since there would probably be little prospect of getting another Mini 60 if we missed this chance, so an instant decision that it had to be done, drop everything and collect the bike following week.

As it happened, the potential buyer had already viewed the bike, and accepted that his 6-foot 5-inch frame wasn't suitable for riding the Laverda's tiny bodyshell, so no pressure to get the bike back after all - which was just as well since the English weather suddenly broke the national drought and practically rained solid for the whole of April, making it particularly difficult to book the road test or get good light for a photoshoot. At one point we even had a model booked for a covershoot... but it rained, so that was a washout too!

It just happened while the Laverda was in, that a Tina scooter also went through the workshops, so we snatched a brief opportunity to snap the two rivals together ... but once more the photoshoot was limited to just a few brief shots before the rain came down again...

Now fifty years old, the feature bike behaved impeccably on the road test and, though a real credit to the engineering quality, the Mini 60 made dismal sales - too small, too expensive, and maybe the manual clutch and three-speed gearchange didn't appeal to customers as much as Tina's easy to ride automatic drive.

Laverda nearly lost their shirt on the scooter foray and didn't want to go there again.

The contemporary stories of the Triumph Tina and Laverda Mini scooters are inextricably linked since they were very direct competitors in their time, and the respective pricing studies illustrated a particularly interesting angle to the ongoing commercial rivalry in the fight for sales - which the Triumph Tina won, and the Laverda models comprehensively lost.

With Danny booked to fly out to Cyprus on morning Sunday 6th May, the Laverda road test and photoshoots were finally completed during the preceding week, and the bike returned to Peterborough on Saturday 5th. The Laverda notes became the first completed draft at the Agios Georgios villa just a few days later, in what turned out to be a particularly productive writing break.

Production costs comprised the two runs there-and-back to Peterborough, so burnt off a good £60 of diesel fuel, but seemed well worth the trouble to bag such a rare machine. Peter Smart at Winton in New Zealand made a small donation shortly after last IceniCAM edition 22, so it seemed fairly appropriate to attach his credit to an article in this edition while we were still running NZ related features.