Sponsored by

Terry Keable

East Anglian Cyclemotor Club

Suffolk Section.

There’s always been a certain market for the most economical of motorised transport—or maybe if you prefer, there’s always someone to buy the cheapest of machines, however they may measure up!

In years before the Second World War, the budget powered two-wheeler position was established by common rigid-fork, first-generation autocycles, with 98cc Wallington Butt, Villiers Junior, or 70cc Levis engines. Versions of these autocycles returned in a post-war regeneration, now with sprung forks, and 98cc Scott, Villiers JDL, or Excelsior motors.

Even as Villiers stood poised to advance the autocycle with announcement of their new 2F engine in 1949, the budget transport crown was about to pass to a new evolutionary class of the ultimate cheapest motor cycle.

The Ostler Mini-Auto announced on 20th January 1949 is credited as herald to the post-war cyclemotoring boom in Britain, and others would surely follow. The closing year of the 1940s decade was to introduce a period of boom in what still stands as the ultimate economy in motorised transport. After the autocycle, but before the moped … this is the dawn of The Age of the Cyclemotor!

Though the pioneering Ostler Mini-Auto would probably qualify as the first British post-war cyclemotor, this was a DIY machine-it-yourself engine from a kit of plans and basic set of castings, so the Ostler could barely be considered as anything other than a hobbyist motor, but the stage was set and the next few months would bring more serious contenders…

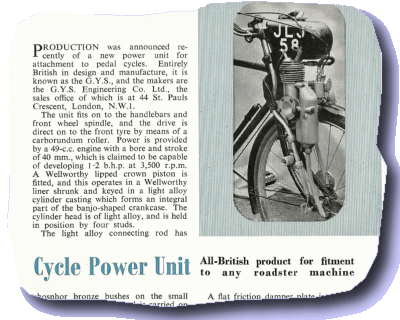

The GYS Engineering Co of Bournemouth listed its cyclemotor attachment engine from summer 1949, but this clip-on unit was contrastingly presented as a proper production machine and represented a truly practical proposition for commercial sales from a marketing office at 44 St Pauls Crescent, London NW1.

The motor comprised an all-alloy, one-piece crankcase & barrel casting, set with a Wellworthy liner and deflector top piston set. While this design reduced the number of component elements, its assembly demands the overhung crankshaft inserting through the case, and the piston fitting down through the cylinder with con-rod pre-attached to the gudgeon pin. Connecting the rod to the big-end eye, the bottom-end is shut by a cast alloy crankcase door, and cylinder closed by a flat-topped cast alloy head.

The GYS is announced to the wider world

in British Cycles and Motor Cycles

Overseas,

August 1949

The theme continued with an alloy exhaust chamber in front of the engine, and an aerodynamically shaped, solder-joint fabricated petrol tank above the motor, feeding down to an Amal 308 carburettor mounted on a cast alloy manifold. The engine assembly was carried on another cast alloy mounting plate, atop aluminium-tube legs mounted from the front wheel spindle. The extensive use of lightweight aluminium materials would expectedly contribute towards keeping forward weight down and, prominently presented on the front of a cycle, the GYS motor unit is certainly a visually impressive piece of equipment.

The earliest traceable reference to the first of our front wheel drive cyclemotors appeared as an entry in The Motor Cycle edition of 23 June 1949, announcing that ‘Deliveries of the new GYS attachment are due to start next week’. The makers were advised as GYS Engineering Co Ltd, High Clements Yard, R L Stevenson Avenue, Westbourne, Bournemouth, Hampshire, with Eustace Watkins as sole London distributors. The retail price was posted at £21, total weight of the complete unit given as 14 pounds, and claimed output of 1.2bhp @ 3,500rpm would probably seem rather an optimistic exaggeration from the primitive 49cc deflector top engine.

Early GYS engines were fitted with a tiny 10mm Champion spark plug, but this was soon replaced with a more commonly available and conventional 14mm plug.

A small passage in The Motor Cycle magazine, dated 1 December 1949, presented that ‘Manufacture under licence of the GYS 49cc two-stroke front-wheel-drive cycle attachment is being undertaken by the Cairns Cycle and Accessory Mfg. Co. Ltd., Stoneswood, Todmorden, Lancs.’

Within just six months, manufacture of the cyclemotor unit was transferred from Bournemouth to the north of England, to be made instead by Automotive Components Ltd, Cairns’s associate company, also at Todmorden.

GYS engine numeration is decoded as the first two digits of the serial indicating the year of manufacture (49 = 1949, 50 = 1950, 51 = 1951), then one or two digits for the month code (1 to 12), and finally the engine number produced in that month.

While very effective for accurate dating, this awkward recording method does however make it extremely difficult to calculate the total number of units manufactured.

Aspects of the forward mounting arrangement could present some drawbacks. It completely eliminated the prospect of mounting any forward carrier or basket. All motor noise comes straight back at the rider, and so too will anything associated with the working of the two-stroke engine: any spillage from the petrol tank, leaks from the fuel tap or carburettor, emissions from the engine decompressor, and particularly smoke and fumes from the exhaust.

It’s not just the smoke and fumes, but what’s in these emissions—oil! In pursuit of manufacturing cheapness, GYS design had blessed the engine with a simple and nasty phosphor bronze plain bearing big end that requires a particularly oily 16:1 lubrication mix to prevent the motor from locking up. A seizure at speed could dramatically lock the engine, dig in the drive roller, and pitch the rider forward onto the road in a potentially dangerous ‘header’.

Having the extended exhaust pipe outlet down around the front wheel spindle, with a pinched and forward facing vent to the tube, GYS was obviously conscious of the oil issue, and trying to minimise effects as much as practical. This, however, would be an incurable problem in the old mineral oil age, and many decades before the advent of modern synthetic lubrication.

Other difficulties resulting from engine location forward of the headstock are clumsy steering effects associated with the higher centre of gravity from the addition of one stone of engine assembly, plus another 6 pounds of filled fuel. Try putting nine bags of sugar in a bicycle front basket if you want to simulate this effect, the impression isn’t positive!

A front mounted engine can also make the cycle particularly prone to falling over when parked. It hardly matters how you park it, stand it by a pedal on the kerb—it falls over. By a side stand—it falls over. By a cycle centre stand, no, it’s still unstable and prone to falling over. Lean it against a wall then—and it still falls over!

There’s really no getting away from the top heavy problem, and this is the reason why many front wheel drive cyclemotors get bashed-up extremities.

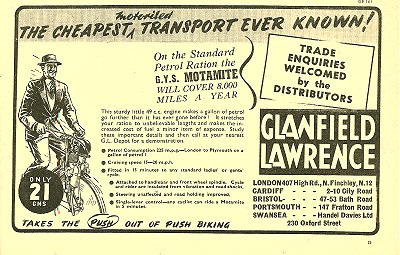

Some advertisements from April 1950 now represented the clip-on kit as a GYS Motamite. (Previously published speculation that these adverts appeared to be illustrating the GYS on a Cairns Roadster cycle frame are, almost certainly, incorrect. The unit depicted is an early model fitted to a Norman bicycle.)

Our test GYS Motamite cyclemotor carries serial 50 9 45, so dates it from 1950 / September / 45th engine in that month produced at Cairns Cycles, Todmorden, Lancs.

To engage engine drive to the wheel, you need to unscrew the knurled alloy knob below the motor on the right-hand leg. Push the knob forward and down in its slot, then lock down into pressure with the tyre. Presumably under fair and flat conditions you might be able to set the motor into degrees of lighter engagement pressure with the tyre, and then the motor should perform a little better due to lower frictional losses.

Finished with a smaller alloy knob, a simple rod rests through the carrier frame, linked to a ‘bell’ strangler on the carburettor intake. Forward position for choke (marked ‘shut’), and pull back for open.

There’s a tap under the left side of the petrol tank, pull for on, and a dual-action decompressor/throttle lever.

The Raleigh cycle this GYS motor is mounted on has a three-speed hub with trigger control on the handlebars, so a range of adequate ratios to choose from to effectively encourage our engine to start.

Within a few seconds of turning on the fuel tap, a jet of petrol spurts out of the overflow vent on the carb top … ah, stuck float! We turn off the fuel again and give the float chamber a little tap, then gingerly pull on the fuel again… yes, seems OK now, but it’s possible that may have flooded the motor, so we opt for trying to start without the choke. Decompress, pedal away in first, turn the throttle and keep pedalling as the decompressor closes … pop … pop, pop, well that was pretty easy!

Easing down the throttle, the bike coasts gently down the road on tick-over with a crisp, gurgling exhaust tone. The GYS certainly sounds like a proper little engine. By the fruity note, the exhaust system appears to be un-baffled, comprising little more than a small expansion chamber with long tailpipe, sounding sharp, but not offensive. Feeding on the throttle, the motor really feels the part, pulling up to speed under load with a typical two-stroking drone … until you get to the teens! Once the motor leaves primary revs, it’s right into a whole world of four-stroking which you’re never going to get through, so this gas transfer barrier effectively limits the performance to what the engine can do.

The four-stroking cause is obviously too small an exhaust port to clear spent gas, but that’s probably not a bad thing since it’ll prevent the motor being thrashed to death, and the plain bearing big-end certainly wouldn’t be particularly happy at any prospect of high revs.

With a thoroughly hot engine, we managed a best on flat of 16mph, which was always held back by staccato four-stroke firing. A long and shallow downhill run peaked at 22mph by the pace bike, though this result was more attributable to the effects of gravity than the motor’s ability to achieve any such dizzying speed.

Speed readily declines against an uphill gradient, but as revs drop and the motor comes under load, it suddenly kicks into two-stroke running and pulls hard against the incline. The effect is so marked, it’s like a switch has been thrown! Considering the little motor’s four-stroke limitations running off-load, it manages to deliver quite an unexpected effort in working up a hill, and any rider can really appreciate that GYS is putting in its best effort at a time that means most to a cyclist. You know the motor is there, working hard when it matters. It’s easy for an owner to bond with such an engine!

There’s the nice and traditional, irregular, two-stroke popping as you shut down on the overrun, and the motor proves docile and tractable right down to a trickle. Stopping at junctions on the decompressor doesn’t really involve re-starting fears from hot magneto set effects since the generator is set well apart from the engine on the opposite side of the wheel, so temperature transference is unlikely to ever be an issue.

The GYS is maybe a little disadvantaged by the lack of any generator lighting set on its Wipac Bantamag, so the rider is going to be wholly reliant on cycle lighting equipment.

Disengaging the GYS from drive mode requires unscrewing the alloy lock-knob, and pulling up the motor platform from both sides of the wheel, or it jams. This concerns the knob now covered with oily exhaust emissions, and grasping the bottom of the magneto set on the opposing side, which has also collected oily drippings. The 16:1 oily emissions just get everywhere on a GYS and you’re going to get filthy! There are so many nooks and crannies that are simply grime traps; if you use one of these things, you’ll never be able to keep it clean. It’ll just end up a complete slime monster!

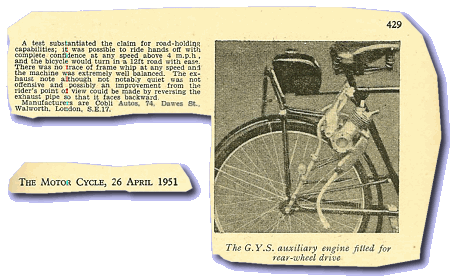

Built by Cobli Autos of 74 Dawes Street, Walworth, London E17, a prototype rear-mounted GYS was presented in a report by The Motor Cycle on 26 April 1951. The rear seat stays of the cycle frame had been replaced by a complex latticework of tubes to enable engine mounting below the saddle. A tubular frame supported the petrol tank above the wheel, and would have obstructed attempts to mount any rear carrier. To accommodate the remounting, a revised and lengthened inlet manifold would also be required; a necessary change unlikely to benefit the performance.

On the plus side, the magazine report commended balance of the model, which would obviously be some improvement over the usual front mounting, but no price for the Cobli GYS was ever posted, and the machine never went into production.

Having licensed manufacture of its clip-on to Cairns since December 1949, it seems that GYS turned over all rights to the licensee sometime during 1951. This transition seems to be reflected in Cairns’s adoption of a new four figure engine numeric system commencing at 5500.

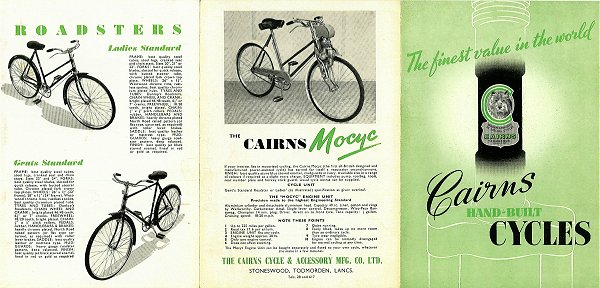

The Motor Cycle presented A Review of the Clip-ons in its edition 15 November 1951, which no longer listed the GYS Motamite, but now presented the same cyclemotor unit as the Cairns Mocyc.

Grasping for opportunities, Cairns also presented cyclemotoring accessories, like their ‘Auxiliary Petroil Tank’, basically a fuel tin with frame mounting holder—possibly in case anyone felt they may need to extend the 84-mile range of their 3-pint capacity fuel tank?

Production of the Cairns Mocyc plodded on over the following years, with steadily flagging sales propped up by greater discounting on the selling price, until it faded from listings in 1956.

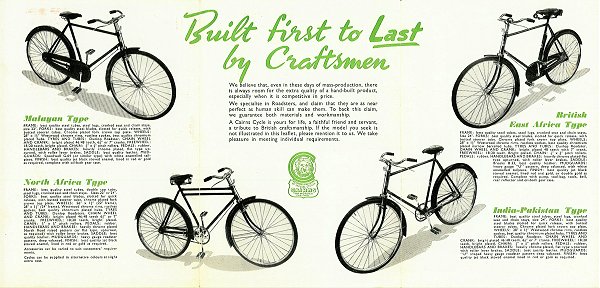

Cairns Cycles were produced in very ‘traditional’ patterns, with heavy frames, and colonial model names harking back to the style and days of a now fading empire … some might say, maybe rather old fashioned!

The Cairns Company similarly faded away.

That’s pretty much all the known facts and established history about GYS, but at IceniCAM, we like to try and bring a bit more to the party—the trouble is that the trail tends to grow a little cold after sixty years.

It all comes down to having the idea to look where no one’s thought to look before: the Kelly’s Directories for Bournemouth!

For whatever reason, these volumes were only erratically published for some years following the war, and only four editions were published to present entries over the relevant period:

The address of High Clements Yard is recorded as owned by Robert Clement, and generally described as an ‘old area behind R L Stevenson Avenue, with lots of stabling and lock-up garages’. It appears that some of these buildings were being variously numbered for use as small business units:

The 1947 edition indicates no sign of GYS Engineering Co Ltd, but records the occupancy of two businesses in Number 5: Clements Motor Eng, and A B Green & Son, General Engineers. Address 9A is listed to a ‘Cab Proprietor’.

The 1950 edition indicates address Number 5 as Clements Motor Eng, GYS Engineering, a window display company, and other occupancy to William J Young—Dairyman.

The 1952 directory contains no trace of GYS, and indicates Number 5 as lock-up garages to Clements Motor Eng, and further storage for the window display company. Address 9A is listed to Westbourne Engineering Co—proprietor A J Green; Clesly—builder; and Ives Motor Eng. Ltd. engine reconditioning with head office in Leeds. Address 9B is listed to Chapeltown Light Industries, Precision Engineers, and other occupancy to Bournemouth Motor Engineering.

The 1955 directory still indicates address 9A as listed to Westbourne Engineering Co—proprietor A J Green, and Clesly—builder. Address 9B to Chapeltown Light Prec.

Apart from the Bournemouth directories, another obscure reference can be found on page 591 of the December 1949 edition of British Cycles and Motor Cycles Overseas, headed ‘GYS Engineering’ … ‘F R Sampson has resigned from the board of GYS Engineering Co Ltd, and as a result the firm has decided to close its London sales office. All correspondence will be dealt with in future at the head office and works, 9a R L Stevenson Avenue, Westbourne, Bournemouth.’

Qualification of the 9A address pretty effectively confirms that either A B Green or A J Green (presumably the son) represented the ‘G’ in GYS. Despite his ‘dairyman’ occupational entry, sharing the same address at exactly the same time might appear just too circumstantial for William J Young not to be involved with the business, so he probably represented the ‘Y’, and that F R Sampson (director) was almost certainly the ‘S’.

Therefore, GYS is seemingly the surname initials of Green, Young and Sampson.

It would appear that (1947) A B Green & Son General Engineers, represented as GYS Eng in 1950, and became (1952) Westbourne Engineering Co—proprietor A J Green, when the son seemingly adopted the business. Due to the ‘transition’, it’s unclear whether the A B Green (father), or son A J Green were represented in the GYS cyclemotor, but their engineering business certainly played a major involvement in its production, though it’s probable that other subcontracted services may have been required.

June 1949—GYS Cyclemotor announced at £21.

December 1949—F R Sampson resigns from the board of GYS, and licensed manufacture transfers to Cairns Cycles in Lancashire.

1950—Cyclemotor kit price £22-1s, and from April titled as GYS Motamite cyclemotor kit in some adverts. Also listed as a complete machine called Cairns Mocyc, comprising the GYS mounted on a Cairns Cycle, price posted at £32-1s. By July 1950 the price was being advertised at £34-1s-8d (including purchase tax).

1951—Price continues as £22-1s for the cyclemotor kit. Around 1,000+ engine units are estimated to have been built prior to introduction of a new engine number series during the year (somewhere between February and October 1951).

1952—The cyclemotor kit now relisted as the Cairns Mocyc, price £22-3s-9d.

1953—The official posted price was £21, but during the year became discounted to £16-16s in an attempt to stimulate sales.

1954—Listed price was further reduced to £14-14s. By November the ultimate bargain-basement price was offering a partially assembled kit for just 12 guineas!

1955—Listed price remained at £14-14s.

1956—Marked price increased to £19-2s-3d, though following the seeming clearance of remaining stock over the year, the kit became de-listed.

Recorded engine serials suggest that fewer than 2,000 Mocyc units were produced by Cairns.

Bournemouth directories up to 1955 continue presenting Westbourne Engineering Co with the same proprietor, so, like the departed F R Sampson, A J Green’s involvement with the GYS cyclemotor didn’t seem to transfer to Cairns Cycles in 1950, and he appears to have remained in Bournemouth.

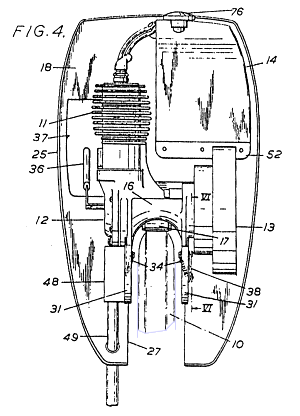

The furthest traceable elements of our competing Front Wheel Drive cyclemotor lead back to patent specification 654,325 application registered on 22 October 1948 by ‘inventor’ David Gottlieb, and filed by Cymo Limited, a British Company, of 364 & 365 Kensington High Street, London W1.

The Provisional Specifications Number 27,567 (22/10/1948) & 32,040 (10/12/1948) mostly describe a ‘general arrangement’ that mainly outlines detail and operation relating to the bonnet cowling, particularly making much of qualifying certain specifics to differentiate it from any other ‘vaguely similar’ cyclemotor that may be made in France.

The Gottlieb application dates precede first announcement of the Ostler engine on 20 January 1949, so this engine concept was obviously being established before any release on the Mini-Auto, and the following murky approaches were seemingly subsequently arranged to ‘assess’ the UK’s first post-war cyclemotor.

During 1949, Richard Ostler was invited to bring his machine to a London hotel, by a ‘potential customer’ interested in discussing the prospect of putting the model into commercial production. While being wined and dined, it seemed his motor was covertly stripped for study, and then re-assembled as if nothing had happened. He immediately recognised the engine had been tampered with and, later, when the occasion had come to nought, was left with the feeling that the design had been pirated. Dick never appreciated quite who the other party really was, and though the Mini-Auto didn’t actually become copied, it was probably a close call!

The Cymo Complete Specification patent was filed on 21 October 1949, and mainly presents general operational descriptions and illustrated details of the bonnet arrangement. At this stage, drawings concerning the power unit still remain vague enough to represent any other similarly arranged front wheel drive cyclemotor. Mounted onto cycles and available for trial runs, prototypes of this ‘novel’ new attachment engine made their first appearance at the Fulham branch of Blue Star Garages Ltd.

A few days later on 9 March 1950, The Motor Cycle magazine presented the first announcement of a new ‘Cymota Cycle Attachment … neat cowling encloses 45cc two-stroke unit’, but thinly veiled beneath its tin bonnet lurked an unlicensed copy of the VéloSoleX engine!

The structure of the patent registration was most fiendishly contrived to completely entwine the Cymota in unrelated patent features that would make it extremely difficult for any legal challenge relating to pirated aspects of the original engine on which it was so obviously based. It’s easy to perceive a VéloSoleX engine origin behind the Cymota patent drawings if you want to, but the patent illustrations still remain ambiguous enough, not to be specifically interpreted.

Further references to the mysterious Cymo Ltd seem strangely unobtainable, and it may be concluded this was probably another imaginative invention of David Gottlieb, adding another level of complication to confuse any possible copyright actions.

Beneath the sleek and sexy, science fiction B-movie, space-age Cymota ‘power-bonnet’ the engine is a very blatant derivation from the period 45cc VéloSoleX. It’s rather like looking in a fairground mirror … that gives some horribly distorted reflection! Main engine aspects appear practically a direct copy (Cymota and VéloSoleX pistons are interchangeable), but the Cymota features Miller magneto set, different exhaust, and high mounted petrol tank for a gravity fed Amal carburettor instead of the Solex low tank with fuel pump.

The press release advised the Cymota as being built by Clifford Motor Components Ltd and subsidiary companies, with Blue Star Garages Ltd, High Street, Hampstead, London NW3, listed as sole distributors for Great Britain. Although stating that the Cymota was ‘not yet in production, orders are being accepted for deliveries starting in June or July’, it was listed at a price of £18-18s.

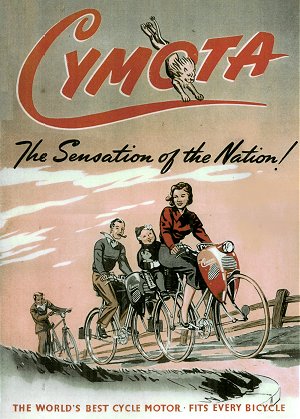

Cymota continued to be promoted over the following months with a series of extravagantly worded ‘bunkum’ advertisements ‘Sensation of the Nation’, and ‘The World’s best Cycle Motor’; promotional literature ‘… produced by British Engineers of World-wide repute’, and ‘… the cheapest form of transport in the world’, while continuing presentations at Blue Star Garages Ltd, Rossmore Court, 57 Park Road, Regents Park, London NW1 invited ‘The general public & the trade to special demonstrations commencing April 17th for 4 weeks’.

Well, seeing as we now happen to be here in 1950, perhaps we might be able to get in on the action! The advert says telephone … so … ‘Hello operator, can you put me through Paddington 4118’ … ‘Yes, we’d like to come down and sample your Cymota for Iceni CAM Magazine’ … ‘No, of course you haven’t heard of us, we’ve come from the future!’

So, we take the steam train down from Ipswich, and just one minute’s walk from Baker Street Station … well, there’s a test machine here, now let’s see if we can blag a road run?

As the petrol tank lurks under the ‘power bonnet’, just a lever fuel tap protrudes through the back panel on the left hand side. Poking through a hole in the right-hand-side back panel, there’s an Amal 308 carburetter with filter/strangler, so we close to choke. There’s a lever above the carburettor, which switches upward to engage drive. By a rod, this tips the motor within the bonnet, so the rider will not see any movement of the cowling.

Cymota was originally supplied with a dual-action decompressor/throttle lever (same as the GYS), but our mount is now differently arranged with a separate decompression trigger on the left handlebar, and a twist throttle to the right. This BSA lady’s cycle also has a three-speed hub with back-pedal coaster brake, so there’s only one brake lever mounted on the left bar to operate the front calliper brake—a most practical arrangement considering the twist throttle our steed is now equipped with. A three-speed trigger change on the right bar allows suitable ratio selection to cajole our Cymota to life, so holding in the decompressor trigger, we pedal away in first, release the trigger as the engine spins, keep pedalling … and the motor starts chugging away.

You can reach forward to clear the choke strangler, then back to the twistgrip to open the throttle … not so much acceleration, as a gradual agricultural-style lumbering … somewhat like riding an exhausted moped in slow motion! Despite having just a plain piece of pipe in place of the original flexi-tube and silencer, the exhaust note is remarkably subdued … rather like the performance. Whether the Cymota bonnet styling might ever have been considered cutting-edge, Flash Gordon, space-age styling in 1950, it certainly doesn’t display any rocket ship performance!

The mph readily drops away against even the most gentle rise, and feels as if the motor is crying for the rider’s pedal assistance at anything other than level running in still air. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with our test machine either, it works exactly as any other Cymota does; it’s just that they’re all completely pathetic! Our pace bike clocked off a best of 17mph on the flat in still air. General running was constantly hampered by four-stroke firing, further revs being limited by inadequate porting. Reluctantly dragged to greater heights by the overwhelming force of gravity on our long and shallow downhill run, our maximum peaked at 22mph, as measured by the shadowing pace bike.

Cymota has its own generator lighting set controlled by a switch on top of the bonnet, with a Miller headlamp built into the cowling, and wire running back to power a Wipac rear lamp. On this BSA cycle, there is also a tyre driven dynamo set with handlebar mounted cycle headlamp above the Cymota bonnet, so we have opportunity to compare. Click the cowling switch left for on, press the dynamo tag so the little wheel springs onto the tyre, then a run back down the road so the test team can judge the relative outputs as we approach at full speed with all bulbs blazing… well, the Cymota headlamp was larger, but its lamp yellower, while the cycle dynamo lens was smaller but gave whiter light. Overall, the Cymota Miller headlamp was judged to be slightly better.

Returning to mission control, and stopping our science fiction B-movie spaceship on the decompressor, there were clouds of steaming oil smoke rising through the bonnet vents—not a cool look! Neither was the propulsion system in this Flash Gordon fantasy power-bonnet, star-cycle anything to marvel over, the specification within the motor was far from the latest technology. The deflector-top piston, with just a single transfer port was never expected to develop any performance, which was probably just as well, since the plain bronze big-end bearing was barely able to cope with what little power the engine produced. This lowly engineering demanded a liberal 20:1 petroil ratio hopefully to prevent the motor from seizing, which by many accounts, was not an uncommon experience for Cymota owners to experience.

The Mark 1 Cymota continued into the following year, until startling new ‘bunkum’ advertisements in June 1951 announced ‘Good News … new factory in full production … new model Cymota great success’ … blah, blah, blah! Oh yes, the price has gone up to 19 guineas, and it’s still being marketed by Blue Star Garages.

Small news items appearing in Motor Cycling and The Motor Cycle of 6th September 1951 seemed to be a sign that a parting of the ways was developing.

‘By mutual agreement with Blue Star Garages, distribution rights in the United Kingdom for the sale of Cymota auxiliary engines have been taken over by Messrs. Cymo Ltd. Leamington Road, Erdington, Birmingham 23. Telephone East 2271/2/3. Blue Star Garages Ltd. will continue to retail Cymota units from their various branches.’

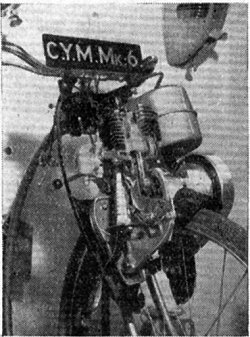

In November, the new ‘Cymota Mark Six’ was advertised in preparation to ‘See it on stand No.62 at the International Bicycle and Motor Cycle Show’.

Whatever happened to the marks Two, Three, Four and Five remains something of a mystery, since the models seem to jump straight from Mark 1 to Mark 6! It’s also noticeable that the posted price is now increased to £25, and that Blue Star Garages no longer appear in the promotion.

Since we’ve plotted Cymota’s seemingly fading fortunes this far, we might as well pop along to the Earls Court Show to look at their latest offering on a little patch in ‘Cyclemotor Corner’, between Power Pak £26-5s (stand 61), and Mini-Motor £21(stand 63), and opposite Berini £24 (stand 60), Mocyc £23-3s (stand 59), Mosquito £27-10s (stand 58), and Cyclaid £24 (stand 57).

In the row behind we find Cyclemaster £27-10s (stand 56), and VéloSoleX £47-18s-4d inc purchase tax, since this was sold as complete cycle and not a clip-on engine kit like the other cyclemotors (stand 55), and next to Cyc-Auto autocycles (stand 54), so there’s a lot more cyclemotor competition getting into the market place since Cymota’s first appearance 18 months ago.

We examine changes to the Mark 6: a new petrol tank that’s probably made up from proprietary press forms, the inlet manifold switched from back of the cylinder to side mounting, the drum silencer changed for a mesh filled cylinder, and engine engagement mechanism lowered from the cylinder head and down on the crankcase.

It’s not entirely convincing that ‘improvements’ to the Mark 6 offered much benefit to the customer and are more probably production cost efficiency changes. Moving the exhaust port meant a new cylider casting and the opportunity was taken to increase the tranfer port size—but it retained the deflector piston.

The Cymota was listed up to 1952, and it’s certain that some of the Mark 6 version were produced—but probably not very many..

Faced with other price competitive and better quality cyclemotors, David Gottlieb seemingly decided against further efforts with the Cymota, and progressed instead to designs of microcars.

The Allard Clipper (1953–55) three-wheeler (one front/two back), only resulted in 22 completed vehicles.

The Powerdrive (1956–58) three-wheeler (two front/one back), renewed the distribution relationship with Blue Star Garages, but sold relatively few due to its high price tag.

The Coronet (1957–60) three-wheeler (two front/one back), again distributed through Blue Star Garages, was the most successful design, selling over 250 examples—until a certain Alec Issigonis designed a certain Mini car for BMC in 1959, and annihilated prospects for small independent microcar producers practically overnight.

Of the two bikes run by the test team, the GYS was much preferred over the feeble Cymota. Being fitted with a lighting equipment set and the ‘clean appeal’ bonnet may possibly have been considered to Cymota’s marketing advantage, but from a rider’s point of view, the GYS felt like a proper motor that an owner could relate to, and GYS was how our test team voted unanimously.

Next—While mainstream motor cycling continues its fixation on ‘bigger and faster’, we seem to be headed in the opposite direction, smaller and slower. The question is—how small can you get, and how slow can you go?

Our world is certainly decelerating for the next edition; this really is Life in the Slow Lane!

[Text and photos © 2011 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Hello Andrew

My name is Philip Hopkins; this morning I was came across the Moped Archive. Being nosey I looked around the archive and saw your notes for the GYS. I have some information, which you may find interesting and perhaps amusing.

I have been involved with the local dealership, Bryants of Biggleswade, since a very early age, my father having bought all of the five bikes he owned in his life from Bryants. Michael, the son of the business was at school with me. As a lad, I worked for them on Saturday mornings cleaning bikes until I left school and started my apprenticeship with Bob King of Bedford. Michael and I remain friends to this day although the business has closed down and Michael is seriously ill with cancer. In the mid-1970s I was a mechanic in Bryant’s Racing team. Bryant’s had premises both sides of Shortmead Street in those days. In the mid 1980s they closed the stores and workshops at numbers 72–74 and relocated them across the road to new buildings at the rear of 25–27. The current stores stock was relocated leaving all manner of old equipment and advertising material lying around in the cellars. I was told that I could have as much or as little of this material as I wanted before the building was sold. I removed everything that interested me. Amongst this stuff were two small engines on sub-frames with drive rollers, obviously intended as cyclemotors. One was minus its fuel tank. Talking to the old members of staff I was told that George Bryant, Michael’s father, had ordered them to be cast into the cellars. It seems that he had ordered six of these GYS units and sold four of them. However, they had a propensity to seize and hurl the rider over the handlebars. He had repaired some of them, hence the missing fuel tank, but he decided not to sell the remaining stock commenting that ‘some bugger would land on their head and be killed’ if he sold the remaining ones.

I was interested to get one running and eventually used it in a number of VMCC Cyclemotor runs. The use of modern two-stroke oil deprived the engine of its ‘Party Trick’. The units were brand new and I have a sheet of Bryant’s notepaper detailing that fact and giving the engine numbers as: 50-8-109 and 50-9-32.

I became interested in the facts regarding the links between the GYS and the Cairns Mocyc. I was able to trace Mr Cairns, living in retirement, and spoke to him on the telephone regarding the history of the Company and the Mocyc. He was an elderly and somewhat bitter gentleman who told me that post-war it was very, very, difficult to obtain raw materials to manufacture bicycles, which was the mainstay of his business and it was only the fact that a large part of his production had always gone for export that enabled him to carry on. At some point, some businessmen had approached him regarding building complete bicycles with engines fitted. At this point he was very unwilling to provide me with any details beyond the fact that he had taken them into some form of partnership in his business and that they had in some way taken over and ‘kicked him out’. He said that they were responsible for the Mocyc and that he was only involved in bicycle production. He seemed to have no recollection of the engine side of the affair or was, as I said, unwilling to discuss it. I visited Todmorden and took some photographs of the closed and boarded up Stackmills Mill where his bicycle works had been. I have some photos of the mill I can scan and e-mail to you at some point.

I hope this somewhat epic missive is of help and or interest to you.

Regards,

Phil ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins

Hi Mark,

I have attached a picture of a GYS Motormite and a Rudge bicycle that I have recently restored. When I started this project, I didn’t know who had made the engine, but I finally figured it after hours on Google, and your Front Wheel Drive article then proved very helpful.

This Motomite one is serial number 49819, so using the decoding from your article this is the 19th unit manufactured in August 1949, only a few months after they started production.

Regards,

Tim Wolfgang,

Denman, NSW Australia.

Cairns’s address of Stoneswood, Todmorden refers to Stoneswood Mill on Bacup Road, Todmorden.

Stoneswood Mill © Copyright Robert Wade

Licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons

Licence

There are two Stoneswood Mill buildings: Upper and Lower. They survive and are currently occupied by P & M Services (Rochdale) Ltd—printed circuit board makers. At the end of the 19th Century, the upper mill was owned by John Walton, a picker maker (pickers are a tool used in the weaving trade). John Walton built the lower mill in 1906.

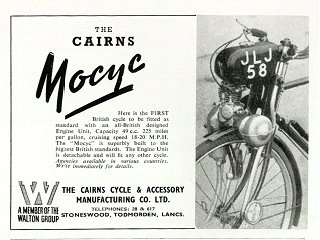

Cairns advertisements from 1950 (left) and 1951 (right)

The two Cairns advertisements above date from April 1950 and November 1951. The earlier advert states that Cairns is ‘A member of the Walton Group’ and this, no doubt is the connection between Cairns and the owners of Stoneswood Mill.

It’s interesting to note that the machine depicted in Cairns’s 1950 advert is neither a Cairns engine, nor a Cairns cycle. JLJ 58 is the 1949 GYS unit on a Norman cycle that appeared in most GYS publicity. Cairns had produced a more up-to-date photograph showing a Cairns engine on a Cairns cycle for the 1951 advert.

The concept of a twin front wheel drive cyclemotor feature was hatched in October 2010, when the GYS and Cymota appeared together on the EACC/IceniCAM stand at the Copdock Show. They just seemed like a logical couple of machines to pair together for a lead article, and both owners were keen on the proposal, so the bikes were added to the forthcoming features list.

Preparation for Front Wheel Drive began in January 2011 when Andrew collated some most considerable Cymota and GYS research file packs out of IceniCAM Information Service library records, to go with Danny to Australia as ‘reading matter’ and, hopefully, conceive some original approach and structure to the text.

Over the years, other publications on GYS/Motamite/Mocyc have done little more than repeating long established facts about the cyclemotor. It’s been quite a while since anyone brought anything new to the party, but that’s hardly surprising when dealing with a 60-year-old cyclemotor—the trail begins to grow pretty cold!

The trick is figuring out a new angle of research and a number of enquiries to various members of Bournemouth and Westbourne Historical Society finally led us to historian, John Barker, who really deserves much credit for coming up with all the old directory references.

It takes a critical combination of experience where obscure local references might exist, and knowing exactly where to find them, and the contribution of historian John Barker really can’t be overstated. We greatly thank him for all his assistance.

The Kelly’s entries proved the big breakthrough (in conjunction with a reference from the 1949 edition of British Cycles and Motor Cycles Overseas), seemingly revealing for the first time the names behind the initials of G Y S (Green, Young and Sampson) and a fractional insight to this long lost world of back street engineering.

One clue however, may sometimes lead on to another question!

Since publication of the article there’s been some speculation as to how a tiny cyclemotor maker on the south coast might have made any connection to licence this business to a minor cycle company in faraway Todmorden?

However, looking on a map reveals this small Lancashire town is only a few miles west from the northern industrial centre of Leeds, and noting that also sharing the same 9A address in High Clements Yard, appears Ives Motor Eng. Ltd. engine reconditioning, who coincidentally register their head office in Leeds!

There’s already been speculation that Ives Motor Engineering might have brokered the transfer of business from Bournemouth to Cairns Cycles, and may open another avenue for continuing research to anyone so inclined to further follow the trail.

The Cymota was supplied by Mick Spacey from Thetford, a long time supporter of IceniCAM, and regular contributor of feature machines (three this year)! Mick was kind enough to drop the Cymota down at the Radar Run in April 2011 and collect it back at the East Anglian Run in May 2011, so saving us any transport costs.

Over the years we’d heard many old stories of what a dreadful machine the Cymota was, but even these can never quite prepare you for the awful reality of actually riding one. The overall impression is that the engine isn’t running properly, but that’s really how it is: utterly pathetic! Everyone at the test session pretty much agreed it was the worst machine that anyone had ridden, and though it started on command and kept running OK throughout the trial, nobody managed to find any kind words for the poor old Cymota.

Cymota is certainly a quirky bygone novelty, probably mostly interesting as a display and conversation piece, but rather hard to perceive as any practical or useful transport.

The GYS was supplied by Terry Keable of Leiston, and kindly delivered to us in later April 2011.

Both bikes needed a little work to finish, just magneto overhaul, timing and cycle adjustments for the Cymota, and fuel system elements on the GYS, so both were pretty much effectively sorted and running within a couple of days.

It was nice to have both machines together for the joint photoshoot, which was fairly straightforward and mainly focussed on the engines, since the cycles on which they were mounted were largely irrelevant. The Cymota gave some interesting challenges, trying to capture the darkened engine cowering within the shadows of the cowling by photographing from outside through the bars of the birdcage. Suddenly the inspiration of an alternative idea, to actually remove the bonnet and picture the bare engine though the inside of the grill! Well, we thought it was novel.

Shooting through the grill doesn’t work… …but turn the

cowl around… …and there’s the shot we wanted.

Apart from a considerable amount of time and effort to research, develop and present the text, production costs were absolutely nothing!

It’s just like they say, cyclemotors really are cheap to run!

Keen to encourage his GYS feature forward to publication, Terry Keable was good enough to make a small sponsorship donation, which proved more than enough to cover the zero cost, and pushed Front Wheel Drive onto the fast track!