The compère steps up to the rostrum, spreads his notes across the lectern, clears his throat, and takes a sip of water from the glass on the corner. He fumbles with the thimble to adjust the microphone angle, flicks the ‘on’ switch, and launches eerily into his narrative…

This tale of old industry weaves a tangled web of intrigue, so you must concentrate on the plot to follow our performance.

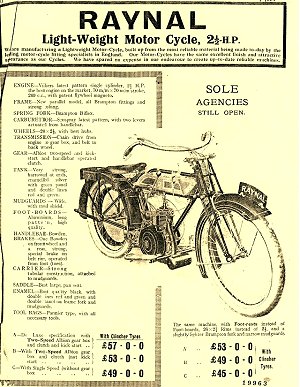

The earliest references to the Raynal Manufacturing Co Ltd at 41–43 Fleet Street, Birmingham, appear around 1914, as a bicycle maker building two-stroke lightweight motor cycles using Precision and Villiers engines, though it is clear the business must have developed from cycle origins much earlier than this date. A preserved copy of their 1922 season trade catalogue, and indicated as ‘List No.48’ probably gives the best insight to activity around this time. The edition illustrates a 2½hp Villiers-powered motor cycle, and offers an extensive range of cycle models, accessories, components and fittings for home trade & export. This year proved the last listing for their motor cycle products, and Raynal continued thereon as a traditional cycle manufacturer.

The budget of 1931 introduced a tax advantage for small engine capacities, giving incentive for the creation of a new class of motorised vehicle. Wallington Butt had introduced his Cyc-Auto motorised cycle in 1934, enjoying for a while the enviable position as sole autocycle producer in an expanding market where demand outstrips his manufacture, and in 1936 the first enthusiast group was formed for these new machines, The National Cyc-Auto Club.

Registered from new premises in Woodburn Road by 1935, Raynal seemed to have carved its niche primarily making batches of ‘branded’ cycles for the trade, so their name would have been practically unknown to the general public in Britain. Raynal badged cycles were certainly sold, however, into export markets, and are generally to be found in the former colonies, particularly North America.

Meanwhile, designer George Herbert Jones has been exploring his own initiative to tap this potential, in an exercise with Villiers to develop a suitable model. With Villiers at Wolverhampton looking round for a custom builder to develop a frame model for their Junior motor, they may have needed to look no further than neighbouring Handsworth. That the prototype Jones autocycle had so much in common with its first production cousin, might appear little coincidence!

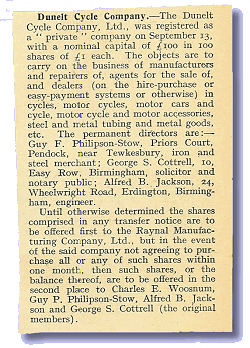

Across the Pennines, Dunford and Elliot reacted to years of world recession by transferring their motor cycle building back to Sheffield and closing the Bath Street Works at Snow Hill, Birmingham in 1931. By 1935, the static market had improved little, and Dunelt decided to abandon producing motor cycles altogether, to concentrate on their core business as steel makers. In 1937, it was announced that rights of the Dunelt Cycles brand had been sold, with A B Jackson, a director at Raynal, accredited with the acquisition. Reacting to a declining market for ‘own make’ cycles, Raynal were buying into a known brand name, and ready access to an established network of retailers.

Back at Cyc-Auto, Wallington Butt’s original own-make engine became replaced by a proprietary Villiers motor in 1937.

And now folks—it’s showtime, as Raynal etches its place in history as one of the pioneers in the advance of the autocycle, becoming the first manufacturer to take up G H Jones’s design licence incorporating the new Villiers Junior 98cc engine.

The curtains sweep away into the wings, revealing a machine on a slowly rotating dais, and the compère strides across the stage to point out features with his cane.

Priced at £18–18s–0d, the original Raynal Auto, with its vertical leaf-sprung pivoting fork suspension, was first announced in The Motor Cycle on 10th September 1937, and followed in Motor Cycling on 15th September 1937. However, the company enjoyed only the briefest commercial luxury of a matter of months before competition followed in its wake.

Villiers held ambitions for its Junior engine, far beyond the expectation from Raynal’s new Woodburn Road Works, and hedged its bets with a further licence issue to Excelsior, who promptly announced ‘a surprise ahead for the Earls Court Show Motor Cycle Show’, where it unveiled its Autobyk version of the new ‘Wilfred’ in November 1937, ready for next season, and priced at 19 guineas (£19–9s–0d).

1938 advertising finds the Dunelt Cycle Co now being listed from Raynal’s address at Woodburn Road, Handsworth, Birmingham 21, but on the motorised front, the floodgates were opening, and the tide was charging in, as a wave of manufacturers announced further ‘Wilfreds’ during the year. James called their model an ‘Auto-cycle’, which became adopted as the name for this class of machines thereafter. HEC arrived at Earls Court with its Levis-engined ‘Powercycle’, Coventry Eagle displayed an ‘Auto-Ette’ prototype, and Norman wheeled out a confusingly titled ‘Motobyke’ autocycle to be listed for sale in the coming season.

With further competition jumping on the autocycle bandwagon and bringing their own models on line, Raynal must have perceived a toughening market ahead, particularly on price, so countered by the introduction of a lower cost £20.10s.0d rigid fork ‘Popular’ version, presented at the Earls Court Show in November 1938, for sale in the following year. Following introduction of the new Popular, the original sprung fork ‘Auto’ model became re-titled as the ‘Deluxe’, with a price now risen to £22–0s–0d. Excelsior also seemed to be feeling the competition, as the price of its Autobyk had been reduced to 18 guineas (£18–18s–0d) by the ’38 show.

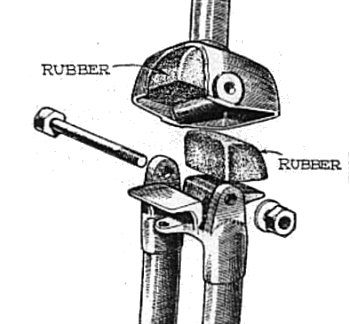

Joining the deluge of autocycles in 1938, the licence was further taken up by Francis Barnett, also announcing its Powerbike 50 at Earls Court, to be ready for sale next season as the J50 (1939, prefix denotes year), and characterised by its unique rubber compression block pivoting fork suspension. This gives us the basis for today’s ludicrous feature—for the first time ever, we get the opportunity to compare wobbly bits on a couple of over 70s!

Actually, you’ll probably be relieved to know it’s not just about the funny forks on these two bikes, they’re both pretty interesting machines in their own right.

Listings for the 1939 Motor Cycle Show at Earls Court reveal separate stand entries for Raynal and Dunelt, though the plan indicates that these were conveniently positioned side-by-side. While the Dunelt stand only featured bicycles, it appears the Raynal stand only featured Autocycles, so the different products of Raynal Manufacturing Co Ltd were being distinctly defined by branding.

Today we have a couple of 1939 Raynals for our feature; one restored, and the other–well, rather weathered and probably waiting for its turn one day too! The chance thing about these two machines is that their frame numbers fall fairly close as 1664 and 1726, so they must have passed through Raynal’s factory at a pretty similar time, then dispatched to the same dealer together, Jas Gross of 379–381 Euston Road, London NW1, and finally being registered in the same block issue as FXK 255, and FXK 266. So here they are, fittingly re-united again for a feature together 70 years later—strange how the elements of fate occasionally produce such odd coincidences!

With its leaf fork, the Raynal is the closest autocycle to G H Jones’s original design, and carries a number of other distinctive features that characterise it from other makes. The back pedal brake is a much appreciated variation, de-cluttering the handlebar controls, and by the greater leverage of leg-power, offering the rider prospects of a better brake. The perennial problem of the pedals rotating when the machine is wheeled backwards, and locking on the brake, is addressed by a cable operated release on the forward actuating arm, which pulls it out of engagement from the ratchet on the pedal arm. The engine mounting bracket comprises a substantial and pleasantly profiled steel casting going right round the top and back of the motor, to double up as bottom bracket housing, and you do have to be impressed just how neatly that detail finishes the frame compared to other makes.

Starting is conventional autocycle, turn on the fuel at bottom left of the tank, rod choke at top left to close the shutter, release the clutch, decompressor, spin on the pedal, drop the decomp and the motor fires right up. Ease back out the choke, pull the clutch onto the latch, nudge the bike off its cast iron centre stand (more practical than the traditional rear stand, but Raynal spaced the legs quite closely, so their bikes can be a little prone to falling over), and we’re ready to go.

When you sit on Raynal Deluxe (1664), and bounce up and down on the saddle, the frame visually sinks at the headset as the leaf fork springs, and the wheelbase extends! It’s easy to imagine this riding sensation might be like being on a small boat in a gentle swell. Just appreciating the suspension is so different does make the first approach a little cautious, but the bounce effect can be controlled by regulating pressure on friction discs at the fork pivot, so may be tuned to suit the optimum damping.

Thumb back the throttle lever while feeding in the clutch, and our Junior engine proves easily strong enough to pull off without requiring any pedal assistance, and the first few undulations in the road are taken with some apprehension, but you soon acclimatise to the effect and barely notice once you get your sea-legs! With disc pressure damping the spring, Raynal doesn’t actually feel much different from any other autocycle and it doesn’t take long before you forget all about the arrangement and get on with the ride.

The note from this stainless exhaust system produces an echoing gurgle at low revs, building to a throaty growl as the speed picks up, but we soon find that some sort of ignition breakdown occurs to limit this machine to 23mph on the flat, and 28mph best downhill. Being its first outing following total restoration, it hasn’t had the running bugs chased out yet, though still allows a good impression of the ride. The balance feels good, and the bike stays a stable course when trying hands free. The back pedal brake stops well when applied, but the ratchet only engages in one position, so an unfamiliar pilot can be surprised to discover it may require up to 359 degrees of back rotation on the pedals before the brake may operate. The rider soon learns that right pedal back is the optimum position for rear braking, which really is needed, as the front brake on this bike proves pretty ineffective.

Illumination never proves much of a strong point for these antique generators. Turning the headlamp switch causes the bulb filaments to glow dimly, but describing them as lights would seem rather optimistic!

Our second Raynal (1726) is a contrastingly battered relic we decided to include for the associated interest, and its weathered patina is the original finish. Aside from having suffered the indignity of a registration transfer, being installed with a JDL motor along the way, losing its back pedal arrangement in favour of a lever and cable operated rear brake, and conversion to twistgrip throttle, this Deluxe still demonstrates the factory ‘lightning flash’ tank coachwork that has invariably been replaced on most restored machines by the later style reproduction decal sets.

The fabricated steel silencer box tells us the engine was transplanted from some paratrooper Excelsior Welbike; a beating heart to still maintain this machine in use today. Since the obsolete Welbikes were only fitted with the one rear brake, they couldn’t qualify for British highway use when the military came to clear them out after the war, so many ended broken up for their cheap donor engines, or exported to the colonies.

Starting is pretty conventional autocycle practice, fuel on bottom right of the tank, raise rod on the left side of the tank to engage choke, decompressor … where’s the trigger? Ah, the cylinder head’s blanked off by a blind bolt—there isn’t one! This means somewhat more pedalling effort required, with the clutch occasionally slipping as we come up against compression, but proves of little consequence since the motor fires up easily with a raucous barking from the stub pipe. Though the choke comes off quite quickly on this machine, we have to hold revs on the throttle for a very pedal assisted take off, as despite all its noisy bluster and smoke, the cold motor isn’t ready to contribute much yet.

As the iron cylinder starts warming around the first mile, the 4-stroking subsides and the motor begins to deliver more effort, settling to a steady droning load tone and comfortable cruising pace about 27mph, with a light tingle of vibration present in the pedals. Best on flat didn’t prove much more, as the pace bike clocked us off at a max of 29mph in still air. Our septuagenarian gave all and lumbered up to 34mph on the downhill run, at which waves of vibration were pulsing through the pedals, and the whole plot doing the shake, rattle and roll as if it was ready to start dropping bits down the road. Miraculously it kept all together to get stuck into the climb on the other side, and crest the rise at 20mph.

Probably aided by the wide operating arc of the Raleigh pattern levers, both brakes proved pretty good.

Handling doesn’t really feel much different from putting any other conventional autocycle frame through the bends. Up ahead, you see the fork blades lightly quivering as the suspension reacts to road surface, but the springy frame doesn’t noticeably bounce much under general riding conditions as the friction dampers effectively smooth out the motion. We are grateful however, that we don’t encounter any potholes along the way.

The Francis Barnett Powerbike 50 with its pivot fork wasn’t made for very long and survivors are quite infrequent, especially fine, original, and complete examples like today’s test machine, which even still has its engine panels. Frame number KG2838 confirms it’s 1939 built, though not apparently first registered till 1941.

Starting the Powerbike 50 is standard early autocycle practice. The motor fires first time, but fails to catch—second attempt proves more successful, so that’s pretty good. Our F–B takes its own time, wanting its Junior motor run awhile before it’ll let us open out the choke shutter and we can think about getting under way.

A gentle pedal-off helps with the cold motor being reluctant on its single-speed gear, though once it’s found a little momentum, pulls steadily up to about 20mph, and thereafter gradually builds up to whatever speed it wants to run under the prevailing conditions. Once we’re under way, the Powerbike lumbers along like some ancient agricultural appliance, and pulling into a light headwind our pace bike records 27–29mph on the flat. Though riders often run these Junior motors at full throttle, it’s not really thrashing them since the deflector motors don’t exactly rev out—with a flat exhaust note, they just drone along at their own pace.

Four-stroking only kicks in on the overrun when we shut down to take the turn at the end of the straight, otherwise the motor runs pretty evenly. Now with a light tailwind on the flat, the pace bike clocks us up to 31mph, then a downhill maximum of 37mph. This F–B didn’t seem perturbed about doing it either, handling the speed surprisingly well with no fuss at all, then laboured up the incline on the other side at 20–21mph, and never asking the rider for any assistance.

Handling was good at all times, and you could take your hands off the bars with no concern about where it might be going. The front suspension works well; looking down you see the forks trembling away, but feel nothing up at the handlebars! There is none of the bouncy ride you might have been expecting as F–B’s rubber compression block wibbly forks don’t feel as if they wobble at all! It rides well, corners confidently, the back-pedal rear brake was certainly effective, and the front stopper very satisfactory too. Braking was perfectly adequate at all times—and it’s rare we say that about many autocycles, never mind first generation veterans of this antiquity!

You could become aware of frequency building up through the pedals approaching 25mph, but running a little quicker found the bike going through this vibration band and they abated again, so the rider tended to run faster or slower of this resonance patch.

Though the pedal brake arrangement caught us out several times by forgetting to flip the reversing latch and backing the rear brake into a lock-on, the control arrangement was much improved over many of the cumbersome inverted lever arrangements of its contemporary stablemates. It certainly resolved the perennial clutch lever access issue and made operation of the autocycle much more natural, allowing the rider to enjoy the ride rather than concentrating on anticipating the next manoeuvre.

Pickup response was a little quirky on this example, for some odd reason it died back with the throttle on full lever, needing to be notched back off max to pull cleanly. The lights were dim, but aren’t they all?

All round, the Francis–Barnett Powerbike 50 was one of the best pre-war autocycles we’ve ridden—a real good old ’un.

With the succession of the original Villiers Junior motor by the Junior DeLuxe in 1940, the Powerbike 50 Autocycle began to evolve. In the transition, Francis–Barnett dropped the Villiers cast aluminium exhaust box, and introduced their own steel fabricated, twin-barrel silencer, with fixing studs protruding from the sides as lower mounting points to retain the engine covers. The long exhaust tailpipe was replaced by a short, curved outlet tube at the end of the silencer chamber, and the light blue metallic colour scheme was dropped for a solemn black with gold lining. The wobbly fork wobbled on through the year, but 1940 sales became pretty insignificant as Europe slipped under a dark shadow. Production was effectively concluded on 14th November 1940, when Heinkels, Junkers, and Dorniers of the Luftwaffe visited Coventry overnight, bombing flat the factory at Lower Ford St.

As their stocks of Junior ‘deflector’ engines ran out in 1939, Raynal also installed the new Villiers 6-port Junior DeLuxe motor for 1940, before production ended during that year, for the rest of the duration. Over the wartime period there appears no positive confirmation about quite how the Raynal plant became deployed, though in common with other cycle manufacturers, munitions work would seem likely.

Francis–Barnett returned to volume manufacture in 1946, resuming with the Powerbike 50 Autocycle, but the wobbly front fork was now gone, replaced by a sprung blade-girder set, which was further succeeded by band suspended tubular girders for 1948. Later that year, Villiers advised customers that the JDL motor would be replaced by the new 2F engine, and Francis–Barnett reacted quickly, introducing their all new design Powerbike 56 model at the November Earls Court Show, ready for the start of the new sales season in 1949.

Raynal’s production also resumed in 1946, and like F–B, Raynal’s wobbly leaf-sprung pivot fork did not re-appear with the emergent machine after the war—but that’s a story for another day…

The stage fades into darkness as the spotlight returns to our compère, still at his lectern. ‘Thank you ladies and gentlemen all, and that is the end of this little vignette, though not quite the end of our autocycling tale… We hope you can find the opportunity to join us again, when our touring performance may return later in the season for our Second Act of the Raynal story’. He hunches over the lectern and casts a beady stare around the auditorium, ‘After all, you do want to know how the story ends?’ Our narrator firmly closes his book of notes, swirls his jacket tails as he turns on his heels, and swishes away through a hidden gap in the curtains.

As the theatre lights glow back on, we rise with the rest of the audience and spill, once more, out into the night to wander again, the dark streets of Birmingham, wondering if we may ever fall upon the mysterious Autocycle Roadshow again—and learn what ever became of Raynal?

At least it’s stopped raining!

Next—away on expedition to the darkest jungle … we’re hunting Monkey! Wonder what we can bag for the pot?

A number of people who’ve been looking at the forthcoming features list and figured what’s in the tubes, have been pressuring for a while to bring this item forward in the programme. The developing text file was called ‘Monbus’, and you get to feel quite affectionate about it when you’ve paged into this as many times as it took to produce such a considerable mega-feature.