Sponsored by Laurence Coates,

East

Anglian Cyclemotor Club

- Suffolk Section

The start of our feature can be precisely defined at December 5th 1877, in the Milanese suburb of Gorla: to Angelo and Teldolinda Bruno, a family of modest means, was born a son—Alessandro Ambrogio Anzani.

While Alessandro grew to show little academic interest, he seemed to develop great mechanical affinity and started work from a very early age at his uncle’s small workshop in Milan.

Nicknamed ‘L’Ange Gabriel’ (The Angel Gabriel), Gabriel Poulain won the ICA professional cycling World Speed Championships in 1906, 1908, 1909 and 1923. In 1921 he attempted to build a flying bicycle. On 9 April that year, he tested it at Longchamps. After a 300 metre run up it took off but only reached a height of 1.2 metres and flew just over 10 metres before touching down again.

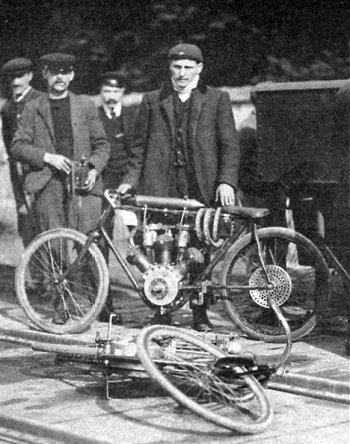

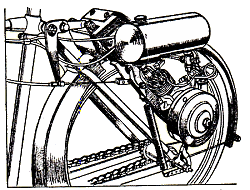

A passion for cycling led to friendship with the French cyclist, Gabriel Poulain and, after completing his obligatory Italian Military Service, Anzani emigrated to live in St Naizaire as a guest of Poulain, raising money by competition in velodrome racing. With the sport only returning modest success, fortune took a turn when Anzani befriended Cornet, an amateur engineer from Marseilles, who was building motor cycles in a small workshop. It was here that Anzani built his first motor, a lightweight two-cylinder engine, more powerful than any other at the time. Mounted in a motor cycle, he raced it with immediate success, winning many races, establishing the class world speed record of 100kph in 1905, and taking the world championship at Ostend in 1906.

In a diversion from racing, around this time he experimented with Ernest Archdeacon’s original ‘Aéro-motorcyclette’, piloting the machine to 80kph, and was captured on the saddle by a photographer in September 1906.

Blériot and Anzani in 1909

With the proceeds of his race winnings, Anzani set up a small workshop at Asnières near Paris, building motor cycles, making engines, and completing a successful float-plane by summer 1907. Sales from the new engines were invested into a larger factory at Courbevoie near Paris, and work commenced on a more powerful lightweight aero engine by adding a third cylinder between the V-twin arrangement. The motor was adopted in the monoplane of the aviator Louis Blériot, winning the Orléans Air Race on 13th July 1909, the Prix de Voyage Cup, and 4,500 Francs of prize money. On 25th July 1909, and using an Anzani engine, Louis Blériot became the first man to fly across the English Channel, to win the prize of 25,000 Francs. The fame reflected well on Anzani, and orders flooded in for all types of his engines: motor cycle, aeroplane and outboards. In 1911, at Navara, another firm called Alessandro Anzani & Co was established for engine distribution, particularly of 6 and 20 cylinder aero-radials. With growing demand for Anzani engines, General Aviation Contractors was established in London in 1911, to supply aircraft and spares to the developing British aviation market. The British Anzani Engine Company was registered on 20th November 1912, at Scrubbs Lane, Willesden NW10, as an agency to the French operation, with G A C becoming majority shareholder, and awarded 1,500 £1 shares as compensation for loss of sole rights.

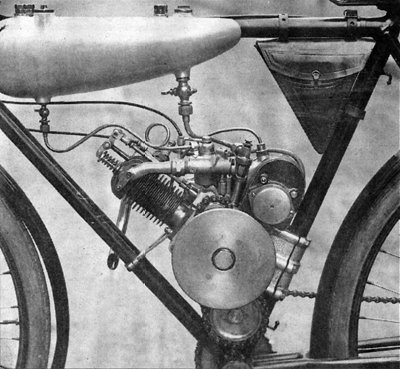

Anzani in 1905 with a

3-cylinder racing motor cycle

From a simple background, Anzani was now becoming enormously rich, and in 1914 built another factory at Monza in Italy to produce 10-cylinder double-star aero-radials.

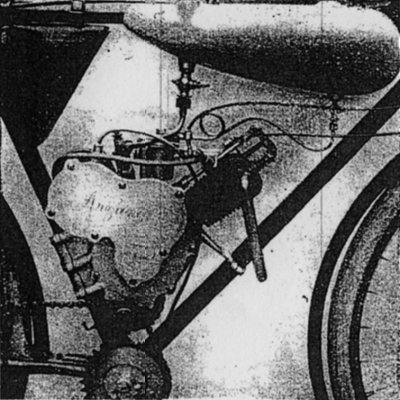

Anzani cyclemotor

Always in search of new challenges, 1920 found Anzani building small racing cars fitted with his air-cooled, twin-cylinder OHV engines, successfully to establish themselves with victories in the cyclecar category across several European countries, including France and Italy.

In 1921, Anzani’s continuing experiments led to thoughts of motorising bicycles, resulting in the building of a compact, belt driving 4-stroke engine of 75cc capacity. These small engines were designed to be easily fitted to normal bicycles and economically running: some 70km to 75km on a single litre of fuel. Arguably, this may be represented among the earliest of pioneering lightweight clip-on cyclemotors: attachment engines destined to become so popular in the post WWII period.

Already a rich and famous man, Anzani grew tired of his inventions and, apart from keeping Monza for sentimental reasons and out of duty to his Italian workforce, sold all of his factories just before his 50th birthday. He retired in 1926 to a villa in Merville–Franceville near Caen in the Calvados region, there to spend the rest of his days and where, at the age of 79, he died on 24th July 1956.

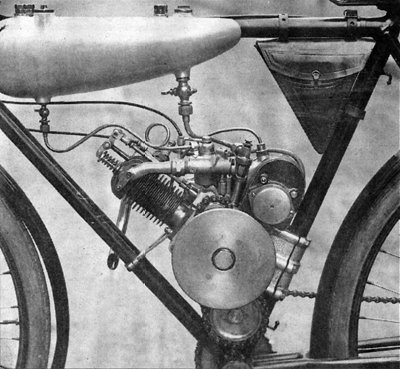

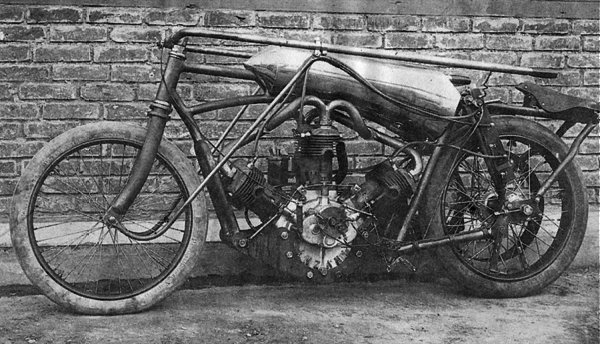

Motos de stayer (cycle pacing machines) were the mainstay of

Anzani’s business.

This 3-cylinder monster dates from 1907.

1922 Anzani cyclemotor

It was in January 2009 that we started our trilogy of Anzani articles and, in the first part, described Anzani’s forgotten cyclemotor of the 1920s. As often happens, more information comes to light after an article is published, in this case, exactly one year later.

It seems that Anzani’s cyclemotor was not so much forgotten as forgotten, rediscovered and forgotten again! In his definitive survey of pétrolettes, published posthumously in 1985, Jérôme Chatouillot revealed the story of the Anzani cyclemotor.

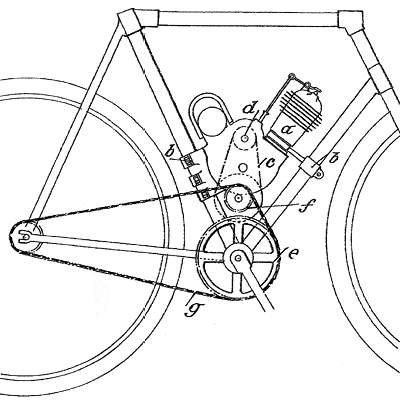

Patent drawing of the Anzani cyclemotor

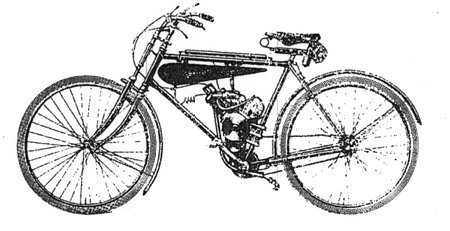

Anzani produced the cyclemotor as a kit to motorize a bicycle and it was shown at the 1922 Paris Salon. The intended market was not the general public but cycle-makers, who would use the Anzani kit to produce a complete, motorized machine.

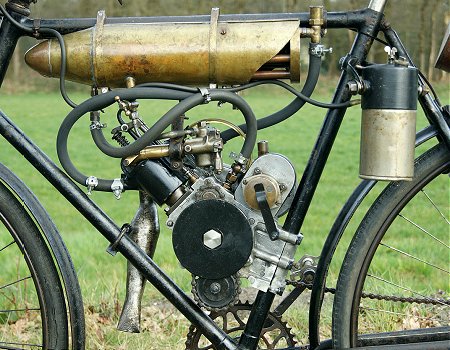

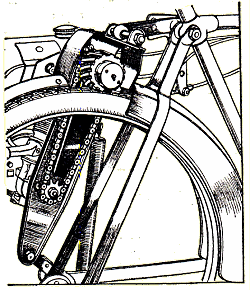

It was a 75cc long-stroke (40mm bore, 60mm stroke) fixed-head OHV engine. The carburettor was a Zénith and the magneto was Anzani’s own, with fixed advance. It is described as having a chain primary drive in the crankcase but photographs reveal that there was a gear drive from the crankshaft to the camshaft and magneto. An external chain drive ran from the end of the camshaft to a countershaft running through the bottom of the crankcase. The cycle’s pedal chain passed over a sprocket on this countershaft, round the cycle chain wheel (which had a built-in freewheel) and went to the rear wheel sprocket. This sprocket had a built-in friction shock absorber. The fuel tank hung over the cycle top tube and had two compartments: 2 litres of petrol in the front one and ½ litre of oil at the back. A contemporary description says that it has automatic lubrication. However, there is no indication of how this worked—most likely is that it was a total-loss system, gravity-fed from the tank with some sort of metering regulated by crankshaft speed. The whole kit weighed 10kg and was offered at a price of 750F.

Anzani was granted French Patent number 535,184 for the cyclemotor, covering the idea of driving through the cycle pedal chain and using a free-wheeling chainwheel. In the autumn of 1923, the French magazine, Moto Révue, organised a Concours du Litre d’Essence. An Anzani cyclemotor took part in this and covered 72.916 kilometres at an average speed of over 64kph on its litre of fuel.

An Anzani at the concours d’endurance de Marly, 18 February

1922

At the same 1922 Salon, Cycles Marant of Neuilly-sur-Seine exhibited a complete pétrolette built around the Anzani kit. The engine had a longer exhaust pipe but was otherwise the same. The fuel tank was similar but hung below the top tube. The cycle itself had 26×1½ wheels, an ABL leading-link suspension fork and two cycle-type brakes, both operating on the rear wheel. The complete machine weighed-in at 33 kilograms and was claimed to be capable of 45km/h.

1922 Marant–Anzani

In October 1922, Anzani announced that it would be producing a complete machine under its own name using the cyclemotor unit and yet another different fuel tank. No more information on this machine has come to light, so we don’t know if any were actually produced.

There are few surviving examples of the Anzani cyclemotor, so it was good to hear from Titus Nietsch (who runs Alltimers—motorcycle classics in the Netherlands) when he found one ... with a difference:

20 March 2014

Dear Mark Daniels,

I want to show you some pictures of a motor cycle I recently purchased in the Netherlands. It looks very much like the Anzani 75cc clip on engine from 1921, but it is watercooled. I think it is original, only the fuel tank (now with a third part for water and air holes for cooling) has been reconstructed. Since watercooling technique was familiar for the Anzani company I think this could perhaps be a prototype, but I can not find a shred of evidence of such a clip on engine anywhere.

During my search on the internet I was impressed by your Anzani Trilogy with much info on the ‘normal’ clip on engine, so I dare to bother you with these pictures and my questions: have you seen such an engine before or heard about the existance, could it be genuine? If you like I can send you some more detailed pictures.

Kind regards,

Titus Nietsch

Alltimers—motorcycle

classics

Well, that poses a few questions, and the answer to most of them is ‘we don’t know’. We can deduce that the bicycle that the engine is mounted in now is not the original: the pipework has been changed to fit this frame. Despite this, the engine is remarkably original and complete, even with its free-wheeling chainwheel and pedal cranks, which suggests that it survived for many years still all attached to its original bike.

But what of the conversion to watercooling? Is this something done by Anzani, or was it done later by another hand? We don’t know. It’s certainly quite old and, if not as old as the engine, it wasn’t done much later than that. The name ‘Miquel’ has been engraved on the crankcases and our guess (and it is only a guess) is that this Miquel made the conversion and was, rightly, proud enough of his handiwork to put his name on it.

Next—our pioneering Anzani trilogy rides on to chapter 2. Might The Missing Link present a revelation that could turn the cyclemotoring world on its head?

Sponsored by Kevin Bayliss,

IceniCAM reader in Fife, Scotland.

When established in 1912 as an agency to Anzani’s French operation, the British Anzani Engine Co Ltd was solely concerned with the sales of aero engines engineered by Coventry Ordnance Works Ltd for distribution through the offices of General Aviation Contractors at Regent Street, London.

By the end of the First World War, however, a change in Allied purchasing policy had practically frozen the business out of competing for military aero contracts. With relegation to just the making of spares and bidding for government development work, British Anzani faced the post war challenge by production of an 11.9hp 4-cyl side-valve car engine designed by Gustave Maclure, and 60° V-twin engines designed by Hubert Hagens, which found applications in ANEC, Mignet, Hawker Cygnet, Bristol Prier–Dickson, Luton Minor and Buzzard light aircraft,

When AC Cars decided to manufacture their own engines in January 1925 and cancelled their 360 engines a year order with British Anzani, the company was driven to file for bankruptcy the following month. The business struggled along in receivership up to November, when director Charles Fox took the concern over, renaming it the British Vulpine Engine Company.

When Alessandro Anzani decided to retire in 1926 and disposed of his factories, the plant at Courbevoie was sold for a considerable sum to the aeronautical industrialist Henry Potez. Contrastingly, back across the Channel, British Vulpine slumped back into liquidation by July of the same year, to be purchased by Eric Burt and Archie Frazer–Nash, who returned the business to the title of the British Anzani Engineering Company. With the lease on its Scrubbs Lane premises expiring in 1927, the business relocated to a Kingston-on-Thames site to provide engines for adjacent Nash cars, and the developed Hagans V-twin in Morgan cyclecars, and AJW, McEvoy, Montgomery, OEC and Trump motor cycles.

Moving again to a new site at London Road, Isleworth in Middlesex, as years of The Great Depression rolled into the 1930s, British Anzani struggled to find customers for its sporting car engines, and was badly affected as many of its motor cycle customers wilted along the wayside. These difficult times were partly occupied by contract work building concrete mixers and pneumatic road drills, engines for the Bristol Tractor Company, and dodgem boats for Butlins, but by the late 1930s the business had faded to a quiet shadow, employing only around 25 staff and limping along on development work and race engines for Nash, engine refurbishments, spares for old motors, and contract work.

It was very much an ailing company when Charles Henry Harrison took over as Managing Director and Chief Designer in 1938. The ex-JAP apprentice, keen motor cyclist, competitive powerboat racer and Technical Director of the British Motor Boat Manufacturing Co, set about transforming the business with fresh enthusiasm and the introduction of new products like funfair equipment (roundabouts and dodgem cars) that BMBM had formerly produced.

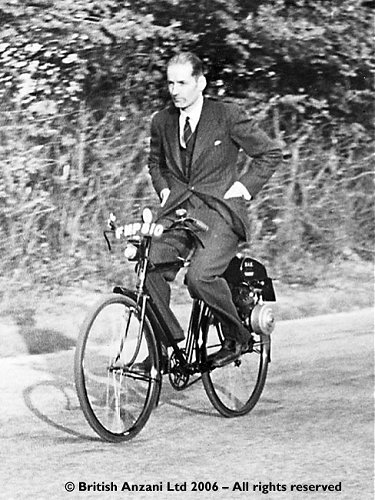

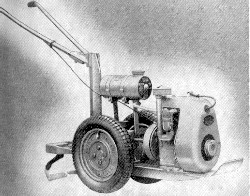

In 1939, British Anzani Engineering produced a prototype BAE Powerplus clip-on motor attachment for a standard pedal cycle. The engine was described as a 61cc undersquare two-stroke of 44.5mm bore × 39mm stroke, driving the rear wheel by friction roller on the tyre. A clutching function could be enabled by lever, which raised and lowered the roller into engagement with the tyre. Back in the age of first generation autocycles, this prototype BAE cyclemotor was quite a visionary concept, but failed to reach production due to intervention of the war.

Charles Harrison riding the Powerplus

The cyclemotor engine was put aside as the need for increased home food production created an immediate demand for more innovative horticultural equipment. This resulted in introduction of the Iron Horse two-wheeled tractor in 1940, and British Anzani also produced their Super Single outboard motor, supplying 50–60 per month to the Admiralty. It also developed flexi-driven propulsion systems for engine driven landing craft, and performed other contract work for the Air Ministry.

In the return to peacetime, British Anzani continued with its established horticultural and outboard products, expanding the themes with introduction of the lighter Planet Junior motor hoe in 1948, and a range of outboards from ½hp up to 40hp. From the racing Unitwin outboard motor, the 242cc and 322cc engine ranges were developed as Anzani returned to motor cycle engine manufacture in 1953, following a break from this production since the 1930s.

These 2-stroke twin motor cycle engines were also adapted to power a number of makes of light microcars, including their own Anzani Astra, Bond Opperman Unicar, Berkeley, Fairthorpe Atom, Peel Manxcar, Powerdrive, and the Gill Getabout.

The Iron Horse, part of

Anzani’s Horticultural range.

Surprisingly, British Anzani failed to capitalise on the post-war cyclemotor boom, and their Powerplus clip-on engine prototype was never seen again. As the engine didn’t progress beyond the development phase, and details were never released to the press, the cyclemotoring world never seemed to appreciate its existence. This remarkable missing link of cyclemotor engineering has neither been previously recorded by any autocycling archives, nor entered in any motor cycling encyclopaedia, remaining completely unknown outside close company circles. With the prototypes long since lost, only a few scant details survived in the personal records of the Harrison family. Fortunately they were donated to the company archive for preservation.

Contrary to what we thought when we published The Missing Link, details of the British Anzani Power Plus were released to the press. Further research has revealed that, on June 22, 1939, The Motor Cycle printed this description of the British-Anzani cyclemotor unit:

The drive from the engine is by chain

to a grooved pulley that bears on the

rear tyre

A SIMPLE yet practical self-contained engine and drive unit for attachment to a normal bicycle has been patented by Mr. C. H. Harrison, of the British Anzani Engineering Co., Ltd. (72–74, Windmill Road, Hampton Hill, Middlesex).

The unit is attached to the frame at two points, and the only extra parts required are a longer rear-wheel spindle and a bolt to take the place of the usual saddle-tube pinch hult. Links pivoting on these two points allow parallel movement on a long pressed-steel back-plate, which is normally mounted on the near side just behind and approximately in line with the fork tubes.

A simple pivot arrangement permits the

drive to be disconnected

The 60 c.c. (bore and stroke 44.5mm. × 39mm.) two-stroke engine is mounted outside this plate, and retained by two of the crankcase bolts and the silencer bolts. On one mainshaft (outside or remote from the backplate) is mounted the flywheel magneto, but the other mainshaft passes through the backplate and carries a 10-tooth sprocket, which is connected by a chain to a 17-tooth sprocket on the 3in. diameter friction pulley. This pulley, which runs on ball bearings, bears on the tyre of the rear wheel, and grip is obtained by means of carefully designed splines.

It has been stated that the engine is held to the backplate by the silencer bolts in addition to the engine bolts; therefore, the silencer is on the inside of the plate and situated between the two runs of the chain, with the outlet towards the rear.

The carburettor is attached directly to the inlet port and fed with petroil from a small cylindrical tank which is bolted to the back-plate immediately above the engine.

Both top and bottom swivel links have a limited travel, and, since they are attached to the back-plate, move the complete unit. This arrangement is provided for disconnecting the drive; thus as the unit moves upwards the friction pulley clears the wheel.

The top link forms a right-angle, and is connected by means of a Bowden cable to a handlebar lever which has a single ratchet. When the lever is raised the unit is lifted, and the bicycle can be ridden in the normal way. At the same time, by an ingenious inter-connection of this cable with a small bell crank, the compression release is depressed, and thus the engine is stopped even if the throttle is not closed.

When the handlebar lever is released the unit drops until the friction pulley is seating on the tyre, due to its own weight and also to the action of a small coil spring fitted between an ear on the back-plate and an arm on the bottom swivel link. Other handlebar controls are the throttle and the strangler.

The outstanding feature of the design is the ease with which the unit can he fitted and its suitability for any pedal cycle. Another point is that the complete unit weighs only 21lb.

Normally the maximum engine speed is 3,000 r.p.m., and the gear ratio is 15.8 to 1 with a 28in. wheel and 14.7 to 1 with a 26in. wheel.

A short road test of the experimental unit clearly demonstrated its practicability. The lever which disconnects the drive was easy to operate, and when released the engine started immediately. Driving was a simple matter of throttle control, as the engine would pull comfortably at speeds lower than that at which the rider could balance. An important point is that the engine is mounted low, so that normal balance is not affected. There was no vibration, and the drive did not slip; it is understood that slip does not readily occur even in wet weather.

Production is not contemplated by the British Anzani Company owing to pressure of other business; hence the design is available to any interested manufacturer.

Next—The interesting oddity in the concluding chapter of our sequence was originally intended to follow on from the Atco Trainer as a sort of ‘spoof’ feature, but its very research led to the distractions of the lost Anzani cyclemotors. Without this machine, we’d probably never have unearthed either of the clip-on engines, so though its association may seem slightly ‘remote’ from our general brief, our trilogy fittingly concludes with - Lawnrider and Beyond.

Sponsored by Peter Wright,

IceniCAM reader &

East Anglian Cyclemotor Club—Suffolk Section.

Planet Motor Hoe and Iron Horse tractor from

Anzani’s Horticultural range.

To complement its range of horticultural products, in the later 1950s, British Anzani acquired the manufacturing rights to the E F Ranger tubular frame Easimow ride-on lawnmower, selling it for a while under its own brand, before developing the machine into their own British Anzani Lawnrider in the early 1960s. This intriguing contraption has a stylish, almost art deco, hollow-cast aluminium frame, and was built in two versions as 18-inch cut Model 512 at 125cc (3hp), and 24-inch cut Model 515 at 150cc (3.½hp). If you crossed an autocycle with a lawnmower, this mythical machine may possibly be what you might get, and wouldn’t every motor cycle enthusiast want to cut his grass on one of these rather than using anything else—so this rather wacky support article concludes our Anzani series with a mini-feature on a top-of-the-range L24 Lawnrider!

The front ‘fork’ comprises a rolled loop of steel plate with the Villiers side-valve motor perched over two angle iron struts that bridge the fork. A centrifugal clutch enables chain transmission to a driving axle across the bottom of the fork, with an outboard belt take-off to the forward mounted cutting cylinder. The fully-floating cutter box pivots in the centre of the front carriage, to follow any ground contours. For navigating the machine between working areas, a lever allows the cutter box to be raised from the ground when cutting isn’t required.

To get Lawnrider going, pull on the plunger of the Ewarts fuel tap under the front mounted tank. Check the ignition switch to run position, and flip the choke lever on the carb. Tweak a bit of throttle lever on the right handlebar loop, a couple of pulls on the recoil and the side-valve motor fires up with a dramatic blast of smoke into the grassbox. As the revs drop, flip off the choke and leave the motor to settle a minute before getting under way.

Thumb back the throttle lever and, as the revs increase, the centrifugal clutch automatically engages cutting cylinder rotation. Described in the trade as a two-way drive system, the cutting cylinder has to be spinning to enable the land drive, which operates by a latched clutch lever on the left handlebar loop. In autocycle fashion, release the trigger to ease out the lever, and Lawnrider pulls away from the drive and we head up the lane on today’s job—to cut the village green!

Lawnrider propels by a spoked, cast aluminium, front drive roller with a bonded rubber tyre, while behind, the chassis rides on three cast aluminium rollers coated with vulcanised rubber tread, that run under the full width of the footrest plates. With a rigid frame and solid rubber tyres, the experience proves shaky approaching Lawnrider’s maximum speed of around 5 to 6mph, which we judge on the basis that a pedestrian needs to jog in order to keep up with us. At such velocity, the central drive roller gets rather twitchy over bumpy road sections, and the rider has to hang on firmly to the butterfly bars to prevent the machine bouncing dramatically towards the verge. Even driving Lawnrider along the road at such low speed certainly imparts a greater appreciation of the contribution of the pneumatic tyre and suspension systems in motoring evolution. Having established the performance, we throttle back and cruise the rest of the way to our destination.

Lawnrider really comes into its own in the off-road section of our test. It proves a much more comfortable ride on the softer grassed areas, and lowering the cutter box, we quickly cut great swathes through the lush green carpet. Approaching the end of a strip, the operator soon becomes practiced to throttle down for the low-speed turn, where you pull round the butterfly bars up to 90°, for the machine to turn in the space it’s standing on, then straighten up the bars to cut back up the adjacent strip.

Down behind the saddle, Lawnrider has a ball hitch for towing a trailer, and proving pretty useful for somewhere to empty the grassbox, without the need to keep breaking off mowing duty for trips to the compost pile at the bottom of the garden.

The Lawnrider was a niche product facing a selection of other manufacturers’ alternatives in the very competitive grass machinery trade and, despite its novelty, attracted only moderate sales within the garden sector. Lawnrider models were discontinued in the late ’60s and the company had completely withdrawn from the horticultural market by the early ’70s.

Outboard motors continued as the main sector for British Anzani’s manufacturing activities over the post-war period, while other developments continued on the business front.

British Anzani had bought the Maidstone Sack & Metal Company in 1961, which was owned by the entrepreneurial brothers, Gerald and Stanley Faull, who then managed to complete a reverse take-over by buying out British Anzani, and turning themselves into the British Anzani Group. The new company expanded through scrap metal dealing, paper conversion, quarrying, civil engineering and service contracting. For a time, the business was very successful, employed over 200 people and moved on to substantial investments in property development and warehousing. As Charles Harrison died in 1973, the remaining outboard motor production was sold off to Boxley Engineering, who finally ceased manufacture of the last engines in 1979. By the late 1970s, high interest rates and a depressed property market brought the property-based enterprise to fatal collapse and British Anzani Group entered liquidation in 1980.

Part of the British Anzani Group’s former property development at the Port of Felixstowe, the Anzani House office block in Anzani Avenue, stands empty and derelict just outside the port area, after being largely vacated by British Telecom at the end of the 1990s, and its other remaining business tenants leaving over the following couple of years.

Anzani House in Felixstowe

The British Anzani name however lives on into the 21st century, now registered to a business supplying marine electrical related products for boats and yachts.

Next—with this final episode concluding our Anzani trilogy, the second support feature must now move on to graze pastures new. With a whole stack of road test mini-features waiting in the can, it could be pretty straightforward to just pick any one out for presentation in IceniCAM 11, but where’s the challenge in that? In the interest of variety, it might be nice to try to extend the second support slot for special off-the-wall features. So, if things work out, we’d like to be following up a related item from IceniCAM 4 back in January 2008, but there’s no guarantee since we’re still trying to track down some crucial supporting material from Motor Cycle & Cycle Trader. Could anyone help with copies from the early ’60s?

[Text © 2009 M Daniels except Chapter 1b—Anzani Again © 2010 A Pattle. Lawnrider photographs © 2009 M Daniels. Water-cooled Anzani cyclemotor photographs © 2014 Alltimers—motorcycle classics. Thanks to Martin Osborne for permission to use source information and licensed copyright of photographs from the British Anzani Archive.

The Anzani series comes in three chapters; the continuity should all add up when we reach the final episode in July. The first chapter The Pioneer sets the scene with an interesting history of a most extraordinary engineer, and tantalises with a tiny fragmented reference to his seemingly lost veteran cyclemotor. We have no idea how many may have been made, but fortunately didn’t have to look far for a period picture of this pioneering 75cc 4-stroke attachment engine from 1921—only at 2 minutes to the twelfth hour did we find that our own IceniCAM Information Service already held one in the extensive archive!

Study of the illustration reveals Anzani’s remarkable originality in taking the primary drive off at half engine speed as a sprocket from the camshaft, down to a crossover countershaft below, from where this version mounts a driving sprocket to pick up the cycle pedal chain.

By a staggering 23 years, the Anzani cyclemotor pre-dates Aldo Farinelli’s Cucciolo prototype that only started yapping its way around the streets of Turin in late 1944. Under licence from SIATA, Ducati commenced manufacturing their famous Cucciolo clip-on in 1946—but who’s the real daddy?

Laurence Coates of the East Anglian Cyclemotor Club, Suffolk Section scores sponsorship credit on the first chapter of the incredible Alessandro Anzani feature.

A year after part one was published and just a few days before the January 2010 magazine was due to be ready for printing, a package arrived in the post. It was a copy of a French magazine, Motocyclettiste number 37–38, that Colin Kirsch had sent us for the Information Service. One of the articles in it was a posthumously-published review of pétrolettes by Jérôme Chatouillot. In it was a picture that looked familiar ... it was the other side of the Anzani cyclemotor we showed you a year ago in Part One of our Anzani trilogy. So, a last minute addition appeared in the magazine and Anzani Again means that there are now four parts to our trilogy!

It doesn’t end there. Even more information came to light in December 2010: the patent number for the cyclemotor’s drive system and the fact that one took part in a 1923 competition to see how far motor cycles would go on a litre of petrol. We’ve merged this information into Anzani Again because the alternative—making it a five-part trilogy—was just too silly.

The Missing Link forms the second chapter of our Anzani trilogy. We’d been playing this trump card pretty close to our chest since incidentally coming across the previously unknown BAE Powerplus cyclemotor in general research on British Anzani. With so many cyclemotor fanatics out there, it was practically inconceivable that there could have been another British clip-on that none of these people even knew existed—but there it was!

Again we have to thank Martin Osbourne at the British Anzani Archive for permission to reference source material and photographic copyright licence, without which, production of the article would not have been possible. Kevin Bayliss up in Fife, Scotland picks up sponsorship credit on this remarkable exposé.

Having dismissed the idea of a five-part trilogy in 2010 when we discovered the Anzani patent, a fifth part, nevertheless, was added in 2013. This happened after we acquired the collection of archive material amassed by Colin Packman (older readers may remember the International Cyclemotor News he published back in the 1980s). Ther, in a file of miscellaneous photocopies, was a copy of a page from a 1939 edition of Motor Cycling describing Charles Harrison’s cyclemotor.

Closing our Anzani trilogy, the Lawnrider was an intriguing diversion with art deco styling. Perhaps because it sort of looked and it rode rather like a bike, and being such an interesting oddity, nobody seemed to mind that it was actually a lawnmower. Spotted in the Norfolk garage of Mick Spacey when preparing the Latin Flair feature on his Douglas Vespino Rally Sport for the October 2008 magazine, Lawnrider was originally intended as a single ‘spoof’ feature to follow on from the Atco Trainer minicar article in that same magazine. The research, however, led to the unearthing of the 1921 Anzani Cyclemotor and 1939 BAE Powerplus Cyclemotor, so it extended to the trilogy that deservedly included sub-features on these lost machines.

| CAMmag Home Page | List of articles |