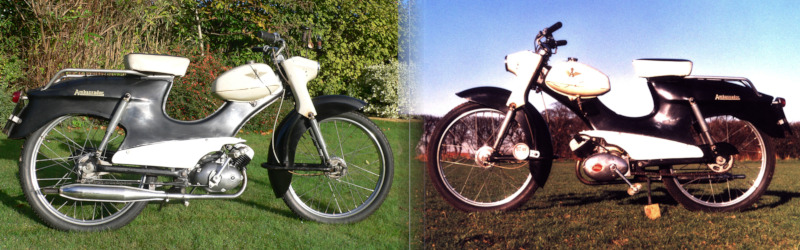

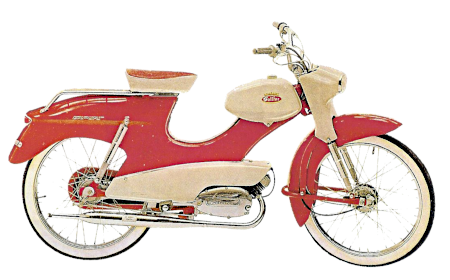

November 1961, sweeping curves, dashing lines, and a striking contrast of black & white. The hand behind the pen could have been Mary Quant, but this stunning up-to-the-minute creation was the work of—Ambassador!

The Ascot company had become well known for the manufacture of motor cycles since beginning production in 1947, but never got round to making an autocycle since these were generally an offshoot product of bicycle manufacturers and they had no such background. All their bikes were fitted with practically every type of Villiers engine, and it was probably a natural progression that when they finally got round to producing a pedal assisted machine that it would use the Wolverhampton factory’s 3K/1 motor.

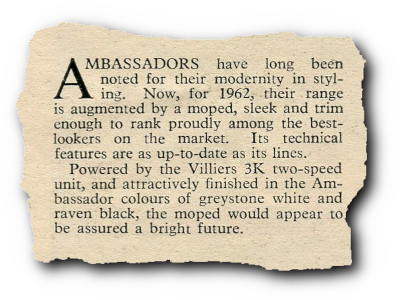

The Motor Cycle, 12 October 1962

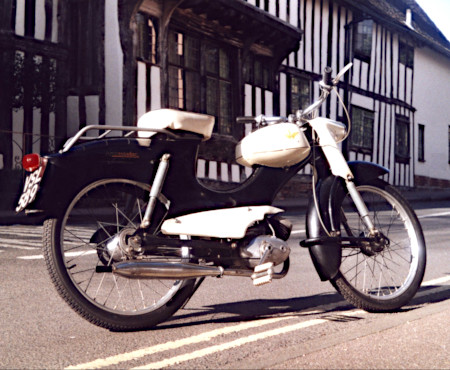

Since Ambassador factored Zündapp products in the UK, accredited motor cycling authorities simply dismissed the moped as being no more than one of these German creations fitted with the Villiers engine, but no Zündapp was ever built like this machine! The selection of cycle components was quite extraordinary for a British home built lightweight. From headstock to tail light the frame comprised a pair of massive half-pressings joined along the centre line, with a welded central construction dropping down to the swing-arm link and side stand pivot. Unusually no centre stand was ever fitted, and the Earles pattern forks are unique for a British moped, though the style appeared on several continental machines and this points to where the front and rear suspension units originated with their galvanised shrouds and gold plastic moulded end links. Other obviously imported parts were the chromed ‘Pranafa’ hubs which were laced into RW aluminized Westwood pattern rims and shod with 2¼✕19 whitewall tyres. And that ‘Pranafa’ rear hub—it’s so unusually wide with such a ‘leaning’ spoke angle that even a professional wheel-builder was struck to make comment on it! Though the petrol tank may appear visually similar to the NSU S2-3 in photographs, this is certainly not the case as the pressings are markedly different. The single seat lifts from a hidden catch at the back, revealing a tool storage cavity with a pump holder tube disappearing into the bowels of the frame. Behind the seat, the long rear frame/mudguard form is topped by an extra long rack. Miller supplied the rear light and horn hiding away in the nacelle, which also houses the VDO speedo kit and European origin headlamp set.

The cycle package generates contrasting impressions from differing angles. With the Earles pattern forks, nacelle and sturdy mudguard, the front end appearance is strikingly solid. From side views the machine looks almost scooter like, while from the rear it seems remarkably long and slender. Sitting on the bike, one is immediately struck by how low the fixed seat height feels at only 31 inches, stretch out to the handlebars and you’re in a sporty forward lean. It’s difficult to work out exactly what the Ambassador was intended to be, it’s certainly an enigma!

All sounds pretty fair so far, but the new machine wasn’t without its design flaws. The stock Villiers 3K and 3K/1 motors were issued to all customers with a 12-tooth front sprocket, which was suitably geared to the Phillips and Norman combinations of 32-tooth rear sprocket (2.67 ratio) on the same 19-inch wheels. Unfortunately the Pranafa hub came with a 35-tooth rear sprocket (2.92 ratio), leaving it badly under-geared compared to the competition. To make matters worse, the mismatched Magura twist-grip to allow use of the Villiers throttle cable that came with the motor set, had a physical stop restricting the carb slider to ¾ opening. This combination left the moped particularly gutless, and meant it was revving its nuts off at a top whack of 30mph. The Ambassador owner must have been very disappointed with his new purchase when the Phillips Gadabout, Norman Nippy, and Norman Lido riders went burning past on their machines—fitted with the same Villiers 3K engine!

Only two of the seven known surviving machines are believed to have the original side panels remaining, which appear so large as to completely cover and prevent access to the carb controls of choke and flood button. From a small hole in the frame behind the petrol tank, operation seems to have been enabled by some sort of remote control wire link, long gone on every example. Presumably this was so frail that it broke in every case, preventing starting, which required permanent discarding of the side panels to enable direct access to the carb. Our feature machine is a fairly complete and original example of the survivors, though has ‘custom styled’ reduced panels to permit side access to the carb controls.

‘The single seat lifts from a hidden catch at

the back, revealing a tool storage cavity’

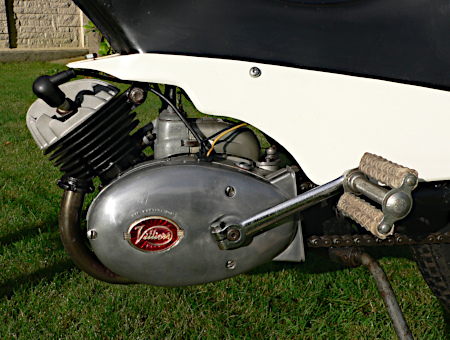

The Villiers 3K engine with cast iron cylinder is specified at 40mm bore × 39.7mm stroke, with 7:1 compression ratio alloy head for a rating of 2bhp @ 5,500rpm, and fed by Villiers own SM10 carburettor with a 12mm venturi.

The crankshaft journal is fitted with an engine speed clutch, which invariably results in accelerated clutch plate wear, and primary transmission is delivered by chain. Since the engine runs ‘the wrong way round’, the primary chain works under loaded tension on its bottom run, allowing the ‘slack’ to drop back into the sprockets on its top return run, so tends to give the engine something of a characteristic ‘running rattle’.

Though a 13-tooth front sprocket would return the gearing to normal expectation, this example runs a 14-tooth (2.5 ratio) to take it 16.6% up on how it left the works, (or 8.3% up against normal drive). This over-gearing had been compensated for with some power increase by boring out the cylinder to 54cc (+0.060"/1.5mm), taking the capacity up by 8%, then facing back the head and reforming of the combustion chamber to raise the compression ratio from 7:1 to 8.5:1. Though visually identical, a different twist-grip and adapted cable now allow full throttle opening and, since our first report on this very same machine back in February 2002 (Wow, 23 years ago!), the motor has received a further compression ratio increase by removal of the 0.63mm head gasket, and bonding of the head joint with RTV high temp red silicone, taking another 0.8cc out of the combustion chamber capacity, so the compression ratio now works out at 10.8:1.

So let’s see how the Ambassador should have gone if it had been engineered a bit better!

It’s a cold day, and starting seems easiest by simply pressing the flood button on the carb until a few drips fall beneath the engine, then kick down on either pedal with an ounce of throttle and within a couple of spins the motor is running. Since the flood worked so predictably, we never even bothered trying the choke, which lifts off automatically as the throttle is opened. The engine breathes through Villiers’s own type SM10/12mm carburettor, and it’s away with a smooth and quiet exhaust note reminiscent of a muffled vacuum cleaner. First gear always seems to engage with a clunk, but there’s no dragging on the clutch once it’s in, and this seems an idiosyncrasy of the motor since we’ve reported this before on other 3K machines. With the raised gearing on our feature machine, it was half expected to need a little more slipping of the clutch to pull away, however the bike is surprisingly readily off the mark. Switching up to second is where the ratio catches up, since first proves to be relatively low and leaves a big jump up to second. This requires buzzing up the revs in first to maintain momentum through the change, and to put this into context, the ratio gap is a massive 39% wider than on a comparative two-gear Rex motor! With a recent ignition overhaul and blueprint timing, the engine feels even better than the last time we rode it; it no longer seems bothered by the ratio jump between gears and delivers sufficient torque to cope unconcernedly with jumping the gear-change gap.

As the revs pick up in second, this Ambassador really begins to pull its top gear quite strongly so there’s absolutely no situation of over-gearing, and it completely overcomes Villiers’s mis-pitched ratios. Villiers motors may have historically acquired a reputation as reliable, though plodding, carthorses, but this tweaked 3K/1 surprisingly dispels this tradition since it revs as freely and smoothly as any other contemporary moped engine.

The brakes are good, suspension is firm, and the ride quite positive with the whole package impressing as being very taut for a moped, not at all like the ‘flexi-feel’ of many lightweights. Due in part to the cornering confidence, the side stand scrapes far too easily on the left and really needs something doing about this detracting problem. Over two decades in storage seem to have deadened the 45mph VDO speedo somewhat; it no longer swings wildly like it used to, though the mileometer still doesn’t work. The needle now seems to move somewhat sluggishly as the bike feels to be faster than the indication, but this time we have a pacer with a sat-nav. Typically cruising in town around general traffic our speedo indicates around 25mph, which feels faster, and our pacer clocks off at 30–31mph. At indicated 29–30mph our pacer reads off 35–36mph, and on two fast light-downhill runs paced at 40mph. Forty was what we calculated from the gearing changes back when the original feature was produced, but we were never actually paced at the time, so it’s nice to confirm that the maths actually works out to match an independent sat-nav.

Kaye Don

This is easily the fastest Villiers 3K engined machine we’ve ever ridden, and it just goes to show what can be achieved from this unlikely engine with some modifications. The 6V × 15/15W headlight is utterly useless along dark country lanes since the ‘infinite beam diffuser’ lamp glass takes what little illumination there is, and scatters it everywhere except the road in front of you, but investigations reveal it’s not the original lens, which should be a Hella 2-77290.

The Ambassador Moped was undoubtedly very stylish for its time and, with a few obvious design errors sorted out, could easily have made a great machine—so what happened to it?

The company’s founder, Kaye Don, was approaching retirement and sold the business to DMW in October 1962, but the new moped was already doomed before this time. With the TI–Raleigh Group choosing to factor Motobécane products from the 1961 season, and subsequently killing off home produced Phillips Gadabout P45 and Norman Nippy Mk4 models, the 3K engine was left with almost no demand. Villiers was hardly going to have much further interest in producing the motor once its two main customers had jumped overboard, so once the pilot batch of mopeds was built up, Ambassador would have found themselves left high and dry without an engine.

‘…there was a fair bit of conversion work

involved to produce the Ambassador. The

engine mounting was completely different…’

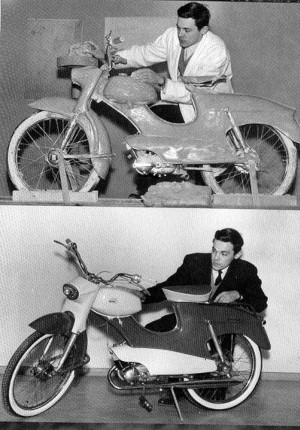

Solifer (top) and Ambassador (bottom)

engine mountings compared

Then there’s still the mystery of that frame? Wide use of metric fasteners on the major cycle parts was most untypical of Ambassador’s imperial background, and the red top on the seat (the feature bike is recovered in black) didn’t really fit with the rest of the colour scheme. It was unimaginable that the little Ascot company would have created the enormously expensive set of press tooling required to make the frame sections, tank, nacelle and side panels, then only have produced a handful of machines. Sure enough they didn’t, but the true source was as unlikely as it was obscure. The stamping of Solinsen ‘Pranafa’ Grafrath on the brake-plates gives away the incredible origin as, Solifer from Finland!

How the connection between these two distant companies came about is likely to remain a mystery, but there was a fair bit of conversion work involved to produce the Ambassador. The engine mounting was completely different for the Villiers 3K/1 compared to the motors that Solifer was fitting in its Export model.

Modelled as a sculpture from clay

by the Finland artist Richard Lindh,

then translated into metal by Solifer.

This extraordinary moped was a

unique work of art in 1960.

The original Solifer Export model was launched on 1st March 1960, and initially powered by a two-speed engine from German company Expresswerke AG as the Solifer Export two-speed Express M-107 type.

Other motors fitted in the Solifer Export were two-speed Pluvier (Dutch) 1961–64, Tomos (licensed Puch) 1962–64, two-speed Pluvier/Berini Thermomat 1964–70, & 3-speed Pluvier/Berini Thermomat from 1969.

The original Express M-107 featured right handed chain drive and left side exhaust, but it seems more likely the Ambassador was based upon the more compatible Pluvier version with its exhaust on the right and putting the transmission out on the left, same as the Villiers.

The Solifer versions all had the spark plug centrally located, where the Villiers came out the side at 45° and might have necessitated an access port cutting in the left hand side panel. Traces of what was probably the original red Solifer colour can be found in places underneath the black Ambassador over-painting, so there’s the match to the seat top!

The model code for the one-year-only Ambassador Moped of 1962, was ‘A-A prefix’, and serialisation was represented irrespective of the model produced, so SPN = Sequential production numbers.

Surviving moped frame numbers recorded on the Ambassador Register list serials 116, 145, 164, 175, A-A 196 (our test machine), 220, 239. Other numbers in between are all part of Ambassador serialised production, so only the prefix indicates the model, and that there would be no other models of ‘Popular’, ‘Sports Super S’, ‘Electra 75’, or ‘Three Star Special’ that would have the same numbers as the mopeds.

The change for 1962 was that the SPN was again reset with the known number range being built from about 10 to 461 on the Ambassador register for 1962. Serialised production over all models would mean that statistical projection couldn’t effectively be applied to figure out how many mopeds were made, and the only thing that statistics could suggest from the serialised list is that it could be as low as seven, possibly as high as 106, but unlikely to higher than 113.

Applying percentages of the five Ambassador models built in 1962: Electra 75 (16), Popular (5), Sports Super S (7), Three Star Special (5), Moped (7), means the moped represents 17.5%. Presuming 500 machines built before production ended with sale of the business in October, suggests maybe 86 mopeds could have been built … we really don’t know, but it looks less than 100.

1963 Solifer Export

In October 1960 the Swedish manufacturer Fram-King signed a three-year sales agreement with Solifer to contract delivery of at least 9,600 Export moped frames to Sweden beginning in 1961, as parts without engines as the Swedes planned to install three-speed DKW ZU-805 motors in them. This seemingly promising export deal was soon compromised by Fram-King’s payment problems, followed by their bankruptcy, and Solifer had to offset the credit losses. The Fram Company subsequently re-financed and, with a new contract, went on to sell Fram-King branded Solifers in Sweden for many years. With the deal concluded with the Swedes, the Solifer Export began to interest other European manufacturers on a wider scale with its elegance and style.

1971 Solifer Export

The next major moped export contract was the one signed in 1961 for the English market with Ambassador Motor Cycles Ltd. The order reportedly included 1,000 pieces for the 1961 post-season, and the Solifer factory would supply at least 3,000 moped frames per year from the beginning of 1962, delivered without an engine, to enable the fitment of the British Villiers 50cc 3K/1 motor. Obviously this didn’t work out as planned, and the deal reportedly fell through due to payment delays.

Beyond the initial batch of frame kits, the Villiers engine supply situation could also have ground the project to a halt, by which time the shortly-to-be-retiring Kaye Don was well into negotiation to sell his company to Harold Nock at the Dawson Motor Works. Understandably, ‘The Don’ wasn’t going to be bothered to find another engine for his factored moped frame, and Richard Lindh’s artwork tragically became a very limited edition in Britain. Solifer continued to manufacture other models of mopeds and light motor cycles until the early 1970s, and still exists today in its original trade as a caravan & camper-van manufacturer; it also factors in Chinese made lightweight two-wheelers for sale under Solifer branding.

Sixty years on from the dawn of the ‘swinging sixties’, and rare surviving examples of the Ambassador moped are still just—(Still) Absolutely Fabulous!