Born in Konstanz–Petershausen in 1867, Ernst Sachs held sporting ambitions from an early age, and demonstrated a capable interest in engineering. As an amateur rider, he celebrated his first successes in bicycle racing, but felt that the bicycle’s bearings did not run smoothly enough, so he sought to improve the mechanics.

After moving to Schweinfurt, Ernst Sachs met the accomplished commercial salesman, Karl Fichtel. In 1894 Ernst Sachs made his first design attempts toward a better bicycle hub, with the first patent registered on 23rd November on bicycle ball bearings with a sliding ball track, which led to the establishment of Schweinfurter Präzisions-Kugellager-Werke Fichtel & Sachs on 1st August 1895, for the production of ball bearings and wheel hubs for bicycles. The founding capital sum was 15,000 German Empire Gold Marks (currency 1873–1914), with Ernst Sachs registered as Technical Director and Karl Fichtel as Commercial Manager. By 1896, Schweinfurt Precision Ball Bearing factories employed 70 workers, who produced about 50 to 70 hubs daily.

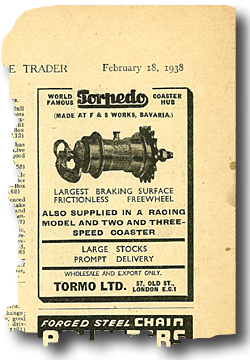

Sachs produced the first commercially successful bicycle freewheeling hub in 1898. He presented his design for a back-pedal brake, and the company launched the F&S Torpedo freewheeling bicycle hub with integrated coaster brake upon the market in 1903. Ernst Sachs was the also first to have the idea not to patent the whole product, but worldwide patent only one component, without which no-one could theoretically build a equivalent modern bicycle. This however was followed by a wave of product piracy from a number of manufacturers at the time, who produced many strikingly similar replicas of the Torpedo freewheel hub.

The breakthrough of the bicycle as a viable means of mass transportation in the early years of the 20th century marked a significant milestone on the road to Fichtel & Sachs’s success, and the company grew rapidly. Within just two years, Fichtel & Sachs had expanded production to 382,000 Torpedo hubs a year, and were already employing 1,800 people.

Sachs’s father-in-law, Wilhelm Höpflinger, registered a patent for the first practical bearing cage, which is still used today in the ball bearing industry.

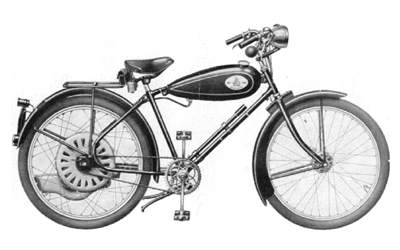

Hercules…

…Bauer…

…and Patria…

… were among the makers

who used the Saxonette motor wheel

When Commercial Director Karl Fichtel died at the age of 48 in 1911, Ernst Sachs took over the sole management of the company, which had then grown to around 2,600 employees. In 1912, to counter high customs duties, Sachs acquired a factory in Cernýš (Tschirnitz) on the Eger river in Bohemia.

Fichtel & Sachs were already one of the world’s leading companies, and had registered over 100 patents for rolling bearings and bicycle hubs before the outbreak of the First World War. A number of Fichtel & Sachs factories were converted to produce armaments and, during the four years of the war, the number of employees increased from 3,000 to around 8,000.

In the Weimar Republic Papiermark hyperinflation year of 1923, Sachs converted to a public company and established Sachs GmbH in Munich as a holding company. By the end of 1927, the number of employees had risen to a highpoint of 9,026; hub manufacture accounted for two-thirds of the total production, the remainder being rolling bearings.

Against the backdrop of looming economic recession in 1929, Ernst Sachs sold the rolling bearing division to the Swedish conglomerate SKF. After paying Karl Fichtel’s heirs with their share, the proceeds were invested in future sustainable developments, such as clutches, small vehicle engines, and shock absorbers.

One of Ernst’s last projects was the development of light two-stroke engines that could be used to motorise many motor cycles of leading manufacturers. Sachs produced its first motor cycle engine in 1930, a 74cc motor that could be fitted centrally in a bicycle-type frame, giving the appearance of a conventional motor cycle. By 1932, a 98cc version was added to the range; this was available as an attachment motor for installation in autocycles, or as a kick-start version for light motor cycles, and for the first time, Sachs even listed its own branded frame to use the motor cycle engine (though it’s likely the frame was made for them by another manufacturer, because Sachs wasn’t really equipped to produce cycle frames).

Ernst Sachs died later in 1932, and his only son, Willy Sachs, took over the company. In 1937 he presented a Saxonette 60cc motor wheel engine that could be installed in most mainstream bicycles.

At the beginning of the Second World War, the number of employees was again returned to around 7,000, and during the war, there was little significant change to the product range. Almost every German tank was equipped with Sachs couplings, but among the 7,000 workforce in 1944, many were forced labourers, and by end of the war, two-thirds of the production facilities had been destroyed.

Despite the damage, production was still resumed by the end of 1945.

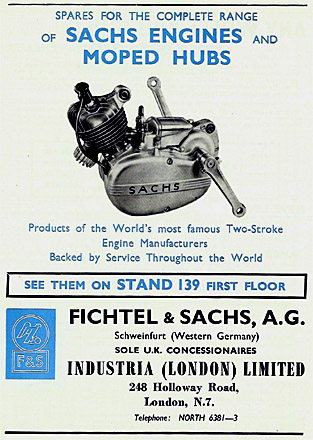

New sales success was achieved at the beginning of the fifties with the famous ‘Sachser’ 50cc moped engine with two-speed gears, and ‘Saxomat’ semi-automatic transmission for cars from 1956, both of which were made in many different versions into the mid-1980s.

With the market success of other innovative developments, the parent plant in Schweinfurt had to be doubled in size in 1969. In addition, several other companies were acquired and the corporation began to take its first steps into North America. In the late 1970s, batches of Sachs-branded Optima-1, Optima 4-S, Optima 5-S, G3, and Supra-4 mopeds were sold into European countries and the USA, all with Sachs engines, but their cycle chassis were all built by the German Hercules Werke, Nurnberg.

Mannesmann AG acquired a majority of Fichtel & Sachs shares in 1987, and continued the internationalisation programme until, by 1995, Fichtel & Sachs was represented around the globe, with 38 production and sales companies. Renamed ZF Sachs AG, the company became part of the ZF Group in 2001.

In 2004, Sachs presented a radical design of ‘underbone frame’ motor cycle under their own branding, and called it the MadAss! In the USA it was sold under Pierspeed & Tomberlin brands as the Madass, and also badged as Xkeleton Trickster, then further sold in Canada as the AMG Nitro. The bike probably originated from German influenced design, and an anodised frame plate displays ‘Sachs Fahrzeug-und Motorentechnik GMBH’, but we’re not convinced, so where was it made?

The familiar looking engine was based on a licensed version of the famous Honda Cub design, in 49cc and 125cc capacities, while the whole machine was manufactured in China and assembled in Malaysia, for international distribution by Sachs Motorcycles.

The simple ‘underbone’ frame comprises a straight and large diameter tube running from the steering headstock to the rear monoshock swingarm pivot, and doubles up as the 1.3-gallon fuel tank in the same manner as a tubone frame design.

A tubular sub-frame assembly to support the seat, exhaust, rear lamp, indicators and number plate, mounts on the main frame, so everything about the machine would be presented in a skeletal style, with no external bodywork or trim.

The three-spoke alloy wheels have the ‘Sachs’ brand cast into the metal, with a 260mm disc on the front, and a 90/90 × 16 tyre, while the back has a 210mm disc and a 120/80 × 16 tyre. Both wheels are barely covered by minimalist plastic mudguards, which feel thick enough to be fibreglass—but they still crack at the front mounts.

Just a glance tells you that the token mudguards are going to be completely ineffective in wet conditions, but they look cool. The front guard ends before the engine begins, so everything will get thrown over the motor and your feet on the footrests when it rains, while the short rear ‘hugger’ will throw everything from the back tyre straight onto the exhaust and the rear electrics. The hot silencer barrel beneath the seat proved particularly vulnerable to water thrown up from the rear tyre, and rotted really badly from the folded seam on the steel body of the can … and a replacement silencer is how much?

The battery is squished into a plastic box with lots of wiring, and inaccessibly situated at the bottom of the main frame tube just below the rear swing-arm pivot, where it is also ideally placed to get everything thrown at it by the rear tyre. Because the battery is very difficult to access, it really needs to be maintenance free, then buy replacements as required, because you absolutely won’t want to be doing that job again…

The frames and fittings are basically the same for the 49 and the 125, with the main difference only being in the engine that is fitted. Despite its skeletal appearance, the frame looks big since the bike stands tall. The wheels & tyres would be wide for a 125, but for the 50 they’re enormous.

There’s monoshock rear suspension and telescopic front forks, with mighty 37mm stanchions in alloy yokes, so they do look the business, but had a bad reputation for diving on the front brake, so required heavier grade oil in the forks to negate the effect.

When this 2004 Madass-50 was acquired in 2010, being an early model it was fitted with the early type rod-operated calliper for the rear disc brake. This was a system that proved particularly troublesome, and was quickly replaced on later models by a more conventional hydraulic calliper set. Parts (including replacement brake pads) for the rod-operated calliper had already become obsolete & unavailable within just six years, and new pads had to be machined from brake material. The mechanical calliper continued to be troublesome, sometimes seizing on the brake, and subsequently had to be adapted with a hydraulic calliper conversion and a master cylinder fitted at the brake lever end.

The rear shock absorber damping had leaked away, so required a replacement monoshock to stop the bike from bouncing all over the road. Several elements of the electrical system had already failed, and trying to keep on top of the constant electrical component failures has proved a full time task ever since, indicators, electronic speedometer, rear light, brake light, headlamps, horn, the electric starter, all sorts of electrical connectors, and even the main wiring harness breaks … they all fail constantly. It’s fair to say the Madass electrics were absolutely dreadful.

Did we mention headlights in there? Oh yes, so while we’re on the subject, the headlights are twin ‘projector headlights’ with a domed lens, two on for high beam and just one on for dip, look cool, but completely ineffective, because you can’t actually see anything by the lights. 12V × 55W of complete uselessness…

If left out in the rain, the socket for the fancy, aviation-style, lockable fuel cap filled up with water, which would then run through the cap seal and into the tank. From the tank, it would find its way down to the carb and eventually stop the engine from running … meanwhile the cheap and nasty fuel tap didn’t seem to react so well with water in it either. The tap failed to close the fuel supply in the off position, and as the fuel level crept up in the carburetter float chamber, it overflowed into the inlet manifold, past the inlet valve and into the cylinder, then past the rings to dilute the engine oil!

The first you may notice of this is discovering a high oil level in the crankcase, so removing the sump plug finds the motor draining petrol, the carburetter float bowl with water in it, and draining the tank finds lots of water in the fuel! The fix is to drill a small drain hole at the lowest point of the fuel cap socket when the bike is leaning on its sidestand. What a pity the Sachs designers couldn’t figure that out.

And, while we’ve touched on the subject of the side stand, it’s a flyaway side stand, which will really get to annoy you. When you park the bike, you hold the stand down with your foot until the weight of the bike takes over when you lean the bike over to the left, then the stand flies up as soon as you lift the weight off. Sounds OK in theory, but if you’re handling the bike from the right hand side, that’s a problem. If anyone brushes against or leans on the bike, the stand flies away and the bike falls over, and when you’re putting it on the stand you may have to do it several times because the stand can often fly up before you’ve managed to trap it. You will absolutely get to hate the stand, so why not put the bike on the centre tand? You can’t, because there isn’t one, which also presents a problem if you need to take out either of the wheels, and the Madass is a heavy bike, so it’s going to be difficult…

OK, the Madass had its problems, but people bought it because it looked radical and seemed like a cool bike to go cruising around on a sunny day. It has no carrying capacity at all, so maybe wasn’t intended as a practical bike for everyday use? Perhaps just personal transport, but it doesn’t even seem very practical for that to us … probably more like a trendy toy for faddy riders who occasionally want to play motorbikes.

So, our UK market Madass has a 30mph-restricted 50cc four-stroke motor rated 2.6bhp @ 7,000rpm (presumably to qualify as a moped so it can be ridden at 16), exhausting through a weedy diameter pipe with a catalytic converter, and four-speed foot-change, in a very heavy frame of 100kg (nearly 17-stone dry weight)! You just know this is going to be pathetic … and it really is the most miserable machine to ride. You have to wring its neck all the time, up through all the gears, while the whining little engine is revving its heart out as you have thrash it constantly just to try and get anywhere at all! Any inclines or headwinds and it really fades, and it’s all you can do to tease the bike up to 30mph on the flat. You might just see an indicated 32mph downhill … it’s slow, and it’s awful!

It doesn’t matter how cool you think it might look, it definitely needs to go better than this, or it will slowly drive you mad…

The 125cc Madass was only rated at 56mph, so that was also a similarly poor performance for a 125 … fortunately, other engines are available…

A deal was done for a pre-used 110cc Loncin engine out of a customised Jincheng Dax, which was being further upgraded to a new 140cc motor. The Loncin had the same four-speed foot-change arrangement in one-down and three-up shift pattern, with electric start, and came complete with a big carb and inlet manifold. The Sachs mag cover with generator set directly interchanged, so the engine would still look practically the same. Advantages of the Loncin motors are that they have bigger main bearings than some other makes, and are generally in a softer state of tune than many of the sportier pit-bike/Stomp XY engines, so the Loncin engines tend to be a little more durable.

Switching the motor over was quite straightforward, but even with the maximum size front sprocket fitted, the gearing proved way too low. Since no direct equivalent gear-up final drive sprocket was available to fit the Sachs rear hub, it came down to machining up a special centreless sprocket to adapt to the hub.

The original saddle was replaced by a custom-made larger pad for a little more comfort, then the final modification was changing to a custom accessory, big-bore, stainless steel exhaust system.

OK, so how does it go now?

Ignition turns on a key switch at the left-hand headlamp bracket, fuel turns off–on–reserve by a lever tap at bottom left of the frame tank. There’s a rotary choke trigger beneath the left-hand bar set to thumb on for starting, and press the starter button (if it works), or use the kick-start (user unfriendly).

Exhibited at the Munich Show in September 2014,

the MadAss 500 concept bike was powered by

an Indian Enfield engine

Above the choke trigger on the left-hand bar set is a horn button (which doesn’t work the horn—as usual), and a combination beam–dip–L&R indicators. We note the front right indicator has inexplicably stopped working (again), and it looks like the main beam projector headlamp is out (probably cooked its bulb again).

The right bar set has switches for lights off–on, and electric start.

The motor fires up on the starter quite readily, though it proves necessary to keep the choke trigger held in to warm for a while, or the motor will die out. The powerful beat of the exhaust note sounds a lot angrier now, giving a deep muffled pulse at lower revs, and snapping to a snarl as you blip the throttle to clear the choke.

The whimpering puppy has grown into a much more savage canine now.

Obviously the digital speedometer isn’t working, because it rarely does, so our pacer peels into tracking position as we pull away.

There are now bags of useful torque from the 110 motor, so our Madass doesn’t need to be revved up through every gear anymore, just lightly feeding in the throttle is easy enough, and you can change up to the next gear early and continue using the torque, while the exhaust delivers a powerful thumping tone—hmm, nice!

It’s a bit of a strange riding position, feeling tall at the back, as if you’re sitting on a perch, with forward weight onto your arms, and we’re not sure quite which race of human being the frame was modelled upon. It does make the handling feel a little strange.

Snapping from the second junction in first, we click into second and twist on more throttle, and the Loncin delivers its power on command with a strong blast of acceleration, then snick into third and maintain the rate of climb. The response is strong through into top, accompanied by an angry snarl from the exhaust, which makes it sound as if it really means business now.

Without a working speedo, we really don’t know how we’re doing, so dip into a crouch and hold flat out on the straight, at which our pacer clocks us off at 57mph. The gearing feels about right since it did seem to need that extra dip down to tease out that last couple of mph.

Braking the speed off at the end of the straight, the rear brake pads seemed to be complaining with a fair bit of creaking, though worked fine.

Handling was generally sure-footed enough, but there were some road surfaces that induced a degree of tram-lining and required some steering ‘adjustment’ to bring the direction back on track.

The gearbox selected all ratios, but needed some delicate feeling around to find neutral, and guided by the neutral light, at least you could tell when you’d actually found it.

The Madass 50 seems to have ceased production in 2015, when it was replaced by an Electric version Madass E, but sixteen years on from its launch, the Sachs Madass 125 still appears to be in production.

The ZF Group merged Sachs into ZF Friedrichshafen AG in 2011, and today, Sachs branded products continue to be sold internationally by ZF Aftermarket, along with other unfamiliar and meaningless brands that are so typical of multinational conglomerates.

Fichtel & Sachs’s history now seems to be just a small cog in a big corporate selling machine…